BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Wednesday, 6 April 2011

Getting to the 'more'

The hardest part of being a historian is accepting the fact that you may not like the answers you find.

I like to think that I’ve evolved into a more objective historian over the last few years. Ever since “Blog, or Die.” debuted back in 2009, I have become increasingly critical when analyzing the lives of our forefathers. As a result, my blog has become more popular and respected at a professional level. This has led to bigger gigs and better books. In many of my previous works (2000-2009), especially those written for the religious genre, I intentionally focused on the positive aspects of history believing it could be both educational and inspirational. I always believed that history was among our most cherished treasures, but learning about it meant nothing if we couldn’t apply it to our lives in some tangible, positive manner.

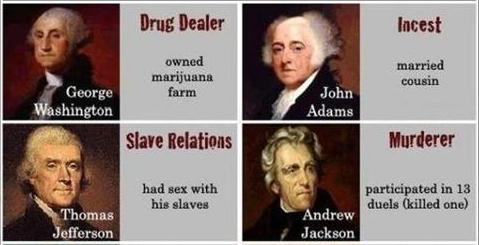

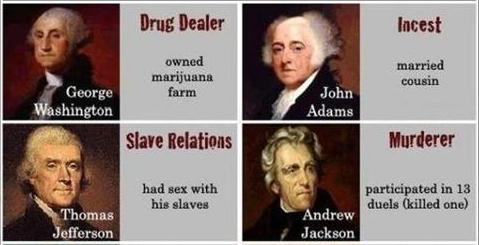

I still believe that. However, what I am learning nowadays is that “applying history to our lives in some tangible, positive manner” doesn’t always translate into a ‘DO.’ Many times it translates into a ‘DON’T’. In other words, there are many times when we should not admire or emulate these men. Far too often people try to separate the good from the bad when discussing our nation’s legacy. We don’t want to acknowledge that George Washington was a slaveholder, or that Mickey Mantle was a womanizing alcoholic. We only want to remember George’s honesty and Mickey’s homeruns.

Unfortunately looking through rose-colored glasses is NOT the way to preserve and present proper history. We must come to terms with the fact that many of our icons, like a Washington, Jefferson, Jackson or Lee, viewed women as inferior and African-Americans as property. We must accept the reality that they were often erroneous in their beliefs and conduct.

I used to get angry at other historians who were considered by many to be ‘naysayers’ or ‘overly-negative’ in their work. I now understand exactly where they are coming from. Historical figures have always been presented to us on a pedestal. For us to simply ignore their wrongs in favor of their rights does a great disservice to their memory. Worse off, we are being dishonest to ourselves and our readers when we only present the histories that we are comfortable with.

Admittedly, I was once guilty of this myself. When the vast majority of my work moved over into the secular realm, I immediately became conscious of my own preconceived notions. It was difficult at first, but I had to accept the darker sides of my idols. I also had to accept that they weren’t necessarily idols. I had to look at them honestly as men who could be both applauded and lauded. Only then did I truly see them.

That is what separates a historian from a history enthusiast. Removing our own personal attachment is the challenge. We become historians because we grow up loving history. We are star-struck by the men and women and events that we learned about. As we mature, we realize that there is usually more to the story. As historians, it’s that ‘more’ we should labor to find. After all, that's part of the story too.

Image source: PunditKitchen

ADDED 4/7: Yesterday’s post generated some interesting conversations between a few historian friends and me. The general consensus was that we can acknowledge historical figure’s flaws and weaknesses while honoring their accomplishments, character qualities, and positive contributions to our nation's history. At the same time we must be conscious not to allow our own personal biases influence how we analyze them. That’s a given. We also agreed that selective memory or hero worship distorts scholarship and inflates historical figures to mythical-like proportions. The reality is that most of our so-called “heroes” would never live up to our expectations. The strangest part of it all is that we will never meet any of these people, yet we often feel some kind of personal connection to them. So here you have the dilemma of the impersonal becoming personal. Finally we acknowledged that what may have been acceptable then may not be acceptable now and therefore we must keep things in context. I have a friend in the National Park Service who is considered a leading authority and penned one of the most critically-acclaimed Civil War books ever published. He once told me that he had absolutely no historical heroes and that he looked at people simply as they were. That puzzled me at the time, but now I get it.

Tuesday, 5 April 2011

Save the date(s)

As April is the official kick-off of the Civil War Sesquicentennial I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity to do some shameless self-promotion. On April 30th I will be presenting a lecture on the gallant boys of the 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteers and hosting a screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights” (*both events twice) at the CarnegieCarnegie’s annual Civil War Weekend (See schedule). On May 15th I will be hosting another screening of “The Angel...” and providing producer comments at Manassas Museum (Details here). I am also pleased to share that my book The Civil War in Spotsylvania County (VA): Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads has been selected as the book of the month on the Rappahannock Regional Library’s Sesquicentennial website. (For all of my Civil War books, please visit Amazon.com.) Finally, I am very happy to announce that I will be returning to the Gathering of Eagles at historic Winchester Courthouse on June 4th, where I will be selling/signing books and DVDs in the author’s area.

As April is the official kick-off of the Civil War Sesquicentennial I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity to do some shameless self-promotion. On April 30th I will be presenting a lecture on the gallant boys of the 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteers and hosting a screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights” (*both events twice) at the CarnegieCarnegie’s annual Civil War Weekend (See schedule). On May 15th I will be hosting another screening of “The Angel...” and providing producer comments at Manassas Museum (Details here). I am also pleased to share that my book The Civil War in Spotsylvania County (VA): Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads has been selected as the book of the month on the Rappahannock Regional Library’s Sesquicentennial website. (For all of my Civil War books, please visit Amazon.com.) Finally, I am very happy to announce that I will be returning to the Gathering of Eagles at historic Winchester Courthouse on June 4th, where I will be selling/signing books and DVDs in the author’s area.

Monday, 4 April 2011

Saint or Sinner?

Often referred to as the most venerated preacher of the 18th-century, Reverend George Whitefield helped spread the “Great Awakening” in both Britain and the North American colonies. As an Anglican Protestant minister, he is also credited with founding the evangelical movement that would lead to the establishment of Methodism. Rev. Whitefield’s reputation as a fiery preacher drew great crowds throughout the colonies to include both non-believers and devout followers. The largest churches in these towns could not hold the 8,000+ citizens who came to see him, so Whitefield began delivering his sermons outdoors in order to accommodate the masses. Sometimes the audience would swell to outnumber the town’s population. As a result Whitefield became one of the most widely recognized public figures in colonial America.

Coming from a poor background, Whitefield managed to get free tuition from Oxford University by acting as a servant for a number of high-ranked upperclassmen. While there he joined an organization known as the “Holy Club” along with the brothers John and Charles Wesley. It was during this time that he became fervently religious and began preaching incessantly about his new-found faith. Impressed with Whitefield’s passion for prayer, the Bishop of Gloucester recruited and ordained him before the canonical age. After preaching in his home of Gloucester, Whitefield departed for the colonies where he was made the parish priest of the church in Savannah Georgia. After a one-year stay, he returned home in order to resume his evangelistic activities. Whitefield openly accepted the Church of England’s official doctrine supporting predestination, but disagreed with their views on slavery. As a result, he left the mainstream movement to form the first Methodist Conference where he served as president before turning the position over in favor of his evangelical work.

As a testament to Whitefield’s skills as an orator, Benjamin Franklin once attended a revival meeting in Philadelphia and was greatly impressed with the reverend’s ability to deliver his message to such a large crowd. Surprised by the mass of humanity surrounding the speaker, Franklin no longer assumed the reports of Whitefield preaching to thousands in England to be greatly exaggerated. Despite his own lack of religious practice, Franklin came to greatly admire Whitefield both for his passion for the Gospel, as well as his ability to reach people of all faiths and denominations. He later recalled that the revival was, “wonderful...change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem'd as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro' the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.” Revered by many, Whitefield defined a unique style of preaching that would elicit emotional responses from the audience. He also granted permission for the publishing of his sermons igniting criticisms accusing him of being over-exuberant in his language. These censures had little effect on the shepherd or his flock. Perhaps his most controversial stance was that slavery had been ordained by God. In 1749, Whitefield campaigned for the legislation of slavery, which was outlawed in 18th-century Georgia. His argument was that no territory could prosper or grow without the support of slave labor. In 1751 he returned to America for a fourth time, viewing the re-legalization of slavery in Georgia as necessary to make agriculture profitable. Whitefield proceeded to purchase slaves himself to work at the Bethesda Orphanage and at Providence Plantation. In an open-letter to his friend Benjamin Franklin, Whitefield presented his conflicting thoughts on those held in bondage. He wrote:

I must inform you in the meekness and gentleness of Christ, that God has a quarrel with you for your cruelty to the poor negroes. Whether it be lawful for Christians to buy slaves, I shall not take it upon me to determine, but sure I am that it is sinful…to use them worse than brutes. …,Although I pray God the slaves would not be permitted to get the upper hand [ie, in revolution against the white slave owners], yet should such a thing be permitted by [God], all good men must acknowledge, the judgement would be just. Whitefield is also credited with being one of the first white preachers to introduce Christianity to African-Americans. He was said to have treated his slaves well (under the circumstances) and upon his death, he bequeathed them to the Countess of Huntingdon.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I found the lack of attention paid to Whitefield’s practice as a slaveholder to be very interesting. Several of the more notable Christian-based publications including Christianity Today and the Christian Classics Ethereal Library either briefly mentioned or completely ignored this fact. It pains me to say anything positive about Glenn Beck, but this is one instance when I found his take to be historically accurate. During his May 14, 2010 broadcast Beck introduced the Reverend George Whitefield to his audience:

I think George Whitefield is a man for today. He's complicated and controversial. We'll get to his views on slavery, which were bizarre, but a man of his time, I guess. He was a man who was years before the revolution, was teaching colonists they could have a relationship with God, they could stand up to authority, he's the man that laid the groundwork for the revolution. He was also strangely for slavery, but when he got to Maryland, when he made his first trek to Georgia from New York, he's coming down through Maryland and he first sees plantations and he is horrified at slavery. He is for slavery, but horrified because he thinks they're being treated terribly, he said you be kind to slaves, they have souls. He didn't make that final leap. I found it so bizarre that he was for slavery, but couldn't get his arms around the way you were treating them, like there is a good way to treat your slave. This contradiction comes up again and again when examining the Founding Fathers: the idea that by treating one’s slaves in a more humane manner, they lessen their sins as slaveholders. Whitefield is a special case as not only did he practice the institution himself, he also campaigned for it. So here we have a man who is celebrated to this very day for his piousness, venerated with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church on November 15, yet guilty of helping to reinstate slavery in 1751 Georgia. Whitefield’s legacy is a perfect illustration of the complexity that exists in the lives of influential whites in colonial America and how we sometimes struggle to remember them today.

Friday, 1 April 2011

That's not what I heard...

Have you ever wondered how the Revolutionary War is taught in England? Last night I did a little research on the Internet and came upon several message boards where Americans and Brits were discussing this topic. The general consensus that I gathered is that they do not discuss the Revolution in the UK. At first glance this sounds preposterous, but we have to remember that England’s history goes back centuries before ours even started. As a result, what was THE seminal event in our nation’s history is just another footnote in theirs. A student from Oxford University posted that on the rare occasion it is discussed, they refer to it as “The War of Independence.” He added that his history classes dealt with British social-history (how the Elizabethans, Romans, Victorians lived) in Primary school (11-) and 20th-Century political history (Nazi Germany, Cold War) between ages 11 -18. The only “American history” he remembered learning about was the Civil Rights Movement.

One graduate student from London posted that the American Revolution was briefly discussed during his education, but in an impartial manner which differed greatly from our romanticized version. He added that many of the “myths” surrounding the event were more readily dispelled in his classrooms. The example offered up was the Boston Tea Party. According to his teachers the protest took place because taxes were too low, not too high (some readers may be surprised to know that taxes were far higher in England than they were in the colonies). In addition he was told that King George III had little power over the colonists meaning the rebellion was actually against the policies of the British Parliament and Prime Minister, not the King.

Another disparity between the US and UK versions was how the war was lost. As British forces were the best equipped and trained army on the planet, it seems impossible that a band of citizen soldiers could defeat them. One UK student said he was taught that the war had ended because British troops were needed elsewhere, not that they were defeated by the Continental Army. Another confessed he was told that the army had simply quit when it became too difficult for them to maintain a supply line across the ocean. I found it very interesting that none of the Brits taking part in this conversation countered either of these claims. (It reminded me very much of the debates I’ve witnessed over the Civil War when folks argue whether the Confederate Army was defeated by the Federals or simply collapsed due to logistics.)

The biggest difference when comparing the US and UK versions appears to be whether the colonists were better off as a result of gaining their independence. According to the UK posts, life without England was dramatically worse for many, especially African-Americans as the British Empire abolished slavery in 1805, 60 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Their theory being that the slave trade would have been eradicated much sooner if the colonies had remained under British rule. Additionally they believe that if America had waited a few more years, the British North America Acts would have likely permitted them to have their own elected Parliament, just like Canada.

In the end most of the UK students participating in the discussion agreed that they had been taught very little or nothing at all about the Revolution. Fewer cared until they got older and began to take an interest in world history. So what have we learned? Obviously there are two sides to every war, each with a different perspective and recollection. The Revolutionary War (or War for Independence depending on which side of the ocean you’re on), is of particular significance as it resulted in the birth of a new country. It is the quintessential example of “David slaying Goliath.” We Americans celebrate the event, while Englishmen tend to ignore it.

I wonder if the Israelites and Philistines did the same?

Thursday, 31 March 2011

An Ugly Truth

Of all the topics that I have written about as a historian none is more complex than the institution of slavery. You may recall the feature that I penned for Patriots of the American Revolution titled: “Race and Remembrance at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello,” or the three-part series presenting a multi-racial view for The Jefferson Project titled “Jefferson and Slavery: Thoughts in Black and White.” I also blogged about: George Washington the emancipating slaveholder, racism and recruiting in the Continental Army, the realities of the 3/5’s Compromise and recollections of Christmas and slavery at Monticello. I am hoping to write an essay that further explores the story of Issac Jefferson as I feel like I am only beginning to scratch the surface of this topic.

You don’t have to be a historian to struggle with this subject. Even those with only a passing interest in our past can find racism difficult to discuss. Oftentimes we take the easy way out by telling ourselves to simply “keep things in context” and “not judge the past by comparing it to the present.” We remind ourselves that what was once commonplace then - isn’t commonplace now. This affirmation helps to dull the sting of racism. The most difficult part (in my opinion) of examining race and our country’s origin is admitting that our Founding Fathers were racist. In order to do that, we must reveal the faults in our heroes. After all these were some of the most brilliant men who ever lived, men who we owe the greatest debt of gratitude to, men who literally did the impossible by establishing a new nation dedicated to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If we were in ancient Greece these men would be our gods.

But…these titans of patriotism were also men who fought for freedom, while simultaneously depriving it to an entire race of people. We know that for certain. Yet in spite of this hypocrisy we are able to reconcile the faults of our Founders when celebrating their life. Who hasn’t admired George Washington’s courage or Thomas Jefferson’s brilliance when visiting Mount Vernon or Monticello? I certainly have. How many of us forget that they were also slaveholders? In recent years Mount Vernon and Monticello have both taken great steps to include the story of African-Americans in their exhibits. This effort has brought about a deeper understanding of slavery in relation to these men, but it still hasn’t enabled us to truly relate to them. To some people, the Founding Fathers are beyond reproach, while others vehemently condemn them. I believe that these extreme-attitudes do a great disservice to their memory. We must remember that they were human, capable of greatness and shamefulness.

My theory is that it is impossible for us to properly judge the Founders because we simply cannot relate to their time and place. We can’t relate because these men were never presented to us in any other capacity. Their likenesses grace our monuments and money. Our forefathers put them up on a pedestal where we continue to herald their achievements today. At the same time we forget that they once viewed African-Americans as property. This is where their racism is most evident. We react to this disturbing fact by subconsciously quantifying the issue to make it more acceptable. We remind ourselves that Washington freed his slaves upon his and his wife’s death and that Jefferson is believed to have fathered children with one of his. This rationalization dulls the sting of their prejudice.

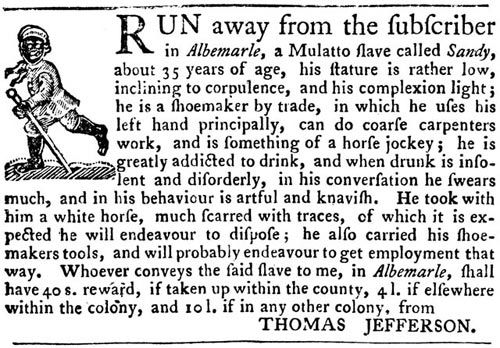

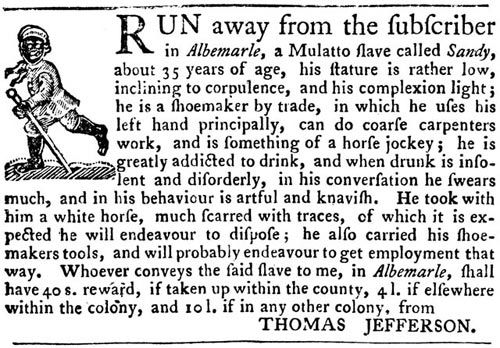

The harsh reality is that no matter how 'well' a slaveholder treated their slaves, at the end of the day they were still slaveholders. A brutal example of this can be found in the inventory records of slaves that were kept by the overseers, as well as the advertisements that they placed in papers. These artifacts prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that these men viewed African-Americans as inferior.

The example above was placed in the September 14, 1769 issue of the Virginia Gazette by Thomas Jefferson who was offering a reward for the return of a runaway slave named Sandy. We know much about the life of the slaves on Mulberry Row and of Jefferson’s affection for many of them. At the same time we see here that he considered them personal property. Therein lays the conflict between admiring our Founders contributions while acknowledging their imperfections. It is a challenge that I still wrestle with no matter how much I read or write about the subject.

Newer | Latest | Older

As April is the official kick-off of the Civil War Sesquicentennial I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity to do some shameless self-promotion. On April 30th I will be presenting a lecture on the gallant boys of the 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteers and hosting a screening of “

As April is the official kick-off of the Civil War Sesquicentennial I would be remiss if I didn’t take this opportunity to do some shameless self-promotion. On April 30th I will be presenting a lecture on the gallant boys of the 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteers and hosting a screening of “