BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Tuesday, 29 March 2011

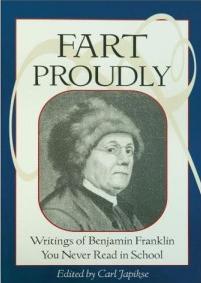

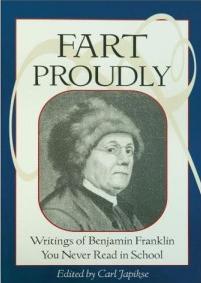

Franklin on Farting

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Among his many contributions to society, Ben Franklin was also a scientist. While living as an ambassador in France Franklin grew disgusted with what he considered to be an elitist’s-approach to science. He believed that too many academic societies were growing increasingly pretentious and far too concerned with the impractical. The Royal Academy of Brussels was an exceptionally arrogant institution in Franklin’s opinion and became the brunt of one of his most notorious essays.

In 1781 Franklin penned “A Letter To A Royal Academy,” which was later more appropriately titled “To the Royal Academy of Farting.” This brilliantly sarcastic letter was in direct response to a call for scientific-papers from the academy. Franklin’s essay called for research into the far-too neglected subject of improving the odor of human flatulence. The original letter was sent to a Welsh philosopher named Richard Price who had an ongoing correspondence with the good doctor. The introduction stated:

I have perused your late mathematical Prize Question, proposed in lieu of one in Natural Philosophy, for the ensuing year...Permit me then humbly to propose one of that sort for your consideration, and through you, if you approve it, for the serious Enquiry of learned Physicians, Chemists, &c. of this enlightened Age. It is universally well known, That in digesting our common Food, there is created or produced in the Bowels of human Creatures, a great Quantity of Wind. That the permitting this Air to escape and mix with the Atmosphere, is usually offensive to the Company, from the fetid Smell that accompanies it. That all well-bred People therefore, to avoid giving such Offence, forcibly restrain the Efforts of Nature to discharge that Wind.

Read the entire letter here.

Franklin’s theory followed in which he discussed how certain foods could affect the severity of flatulence odor. He then called for sanctioned scientific testing to take place while challenging scientists to work toward creating a drug, “[w]holesome and not disagreeable,” which can be mixed with what he called “common Food or Sauces” to render flatulence as agreeable as perfume. He closed the piece by saying that compared to the practical applications of his proposal, all other sciences were “scarcely worth a FART-HING.”

A reprint of this letter was privately published by Franklin and distributed exclusively among his friends. After his death the letter was excluded from any future publishing until Fart Proudly: Writings of Benjamin Franklin You Never Read in School, a collection of Franklin's humorous and satirical writings was published in 1990.

Sunday, 27 March 2011

Two wars with the S.C. Dragoons

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment.

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment.

The Charleston Light Dragoons boast a storied history that stretches from America’s fight for independence to the War Between the States. Founded around 1773, this group of South Carolina mounted infantrymen was originally formed as the Charleston Horse-Guards. During the Revolutionary War, they were known as the Charleston Light Dragoons. The first captain of this unit was a man named Samuel Prioleau whose descendents would ride together as members of Company K, in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry (one being wounded at Pocotaligo and the other falling at Cold Harbor). Their sacrifice followed a long lineage of service by their forefathers. In order to fully appreciate the legacy of this elite unit, one must begin at their beginning.

The original Charleston Horse-Guards were established to perform the duties of reconnaissance and patrolling. Acting in the capacity of mounted militia, these dragoons were among South Carolina’s first cavalrymen or scouts. Eventually the bravado of these units led to an expansion of roles to include combat. Unfortunately, it would be friendly fire that would deal one of the most costly blows to the regiment. According to A Sketch of the Charleston Light Dragoons From the Earliest Formation of the Corps by Edward Wells:

In the stormy times of the Revolution the command is believed to have consisted as several companies. This was the case in 1777 when Major Benjamin Huger, with a detachment from the corps, rode out of the lines in Charleston to reconnoiter for the expected approach of British forces. Not having discovered the enemy in the vicinity, he was bringing his men back, and had reached a point in what is now Meeting street near the Citadel, when they were fired upon with grape from a field piece, in command presumably of some militiamen, who mistook them for the King’s troops. Huger was killed. General Hampton, grandfather of the present general, at that time with the detachment, was riding “boot-leg and boot-leg,” as he expressed it, with Major Huger. The relative of this latter gallant gentleman, the inheritor of his name, and the strong characteristics of the blood, fought under the flag of the Dragoons at Pocotaligo, Hawes-shop, and other hotly contested fields.

In the months leading up to the Civil War the Charleston Light Dragoons were mentioned among the troops guarding Fort Sumter in 1860. They would later join a number of South Carolina militia companies who were consolidated into the 4th South Carolina Cavalry. The 4th S.C. regiment was organized in 1862, by consolidating the 10th and 12th Battalion South Carolina Cavalries into 10 companies including Company K, the former Light Dragoons out of Charleston.

Referred to as an “anomalous unit,” the ranks of the Co. K were reputed to be so exclusive that officer’s resigned their own commissions to serve with ordinary enlisted troops. It is said that the unit carried themselves with a unique flair and a natural assumption of social superiority even over fellow Confederate cavalry. W. Eric Emerson outlined the aristocratic attitudes of the Charleston Light Dragoons, as part of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry in his book Sons of Privilege: The Charleston Light Dragoons in the Civil War. According to the book’s teaser:

Organized much like a gentleman’s social club, the dragoons differed markedly from most units in the Confederate and Union armies, which brought together men of varying social and economic backgrounds. Emerson vividly depicts the dragoons’ two assignments—a relatively undemanding stint along the South Carolina coast and a subsequent few weeks of intense combat in Virginia. Recounting the unit’s 1864 baptism by fire at the Battle of Haw’s Shop, he suggests that the dragoons’ unrealistic expectations about their military prowess led the men to fight with more bravery than discretion. Thus the unit suffered heavy losses, and by 1865 only a handful survived.

Upon its reformation, the 4th S.C. was commanded by Colonel B. Huger Rutledge and served in the 1st Military District of South Carolina from December 1862 until it was transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia in March 1864. Serving under Major General Hampton's Division of cavalry, in the Cavalry Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, they would eventually be transferred to the Army of Tennessee under General Joseph E. Johnston. While under Johnston’s command they saw continuous action in the Campaign of the Carolinas through the spring of 1865, completing their wartime service with less than 200 men.

Sources:

A Guide to South Carolina Civil War Research (The Charleston Light Dragoons)

Historical Sketch and Roster of the SC 4th Cavalry Regiment by John C. Rigdon

A Sketch of the Charleston Light Dragoons From the Earliest Formation of the Corps by Edward Wells

Sons of Privilege: The Charleston Light Dragoons in the Civil War by W. Eric Emerson

Thursday, 24 March 2011

Ligonier Days

Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places, Fort Ligonier, wasn’t too far from our home in Pittsburgh. I remember traveling there on a number of occasions and credit that site in particular for my interest in 18th-century history.

Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places, Fort Ligonier, wasn’t too far from our home in Pittsburgh. I remember traveling there on a number of occasions and credit that site in particular for my interest in 18th-century history.

Unlike Fort Pitt, Fort Ligonier was completely reconstructed and therefore able to hold the attention of a hyper-active child like myself. I believe that my first exposure to re-enactors took place during “Ligonier Days” a three-day festival when living historians, dressed-up as British soldiers and Indians, demonstrated their weapons and tactics. The memory of that event is still very vivid as I was captivated by the experience.

Located in southwestern Pennsylvania, Fort Ligonier was constructed in 1758 for use as a British garrison. During its lifetime, the stronghold served multiple purposes including time as a port of passage for troops en route to Fort Pitt, and as a vital link for the British Army’s supply lines. A number of regulars were stationed there including the 60th Regiment of Foot (Royal Americans), the First Highland Battalion (Montgomery’s Highlanders), the 77th Regiment of Foot, a Royal Artillery detachment, the 94th Regiment of Foot (Royal Welsh Volunteers) and the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment of Foot (Black Watch). Fort Ligonier’s proximity to the French garrison at Fort Duquesne also made it a target.

Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians were driven back by artillery. As darkness fell the remaining forces renewed their attack before retreating back into the woods. The casualty reports following the four-hour assault differed greatly as the French reported taking 100 scalps and seven prisoners, while the British only reported 12 killed, 18 wounded, and 31 missing.

Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians were driven back by artillery. As darkness fell the remaining forces renewed their attack before retreating back into the woods. The casualty reports following the four-hour assault differed greatly as the French reported taking 100 scalps and seven prisoners, while the British only reported 12 killed, 18 wounded, and 31 missing.

In November of that year General John Forbes assumed custody of the newly abandoned Fort Duquesne. He designated the site “Pittsburgh” to honor William Pitt, the acting Secretary of State. He then christened the fort known as Loyalhanna "Fort Ligonier," after his superior Sir John Ligonier, commander in chief in Great Britain.

During the Pontiac’s War of 1763, a coalition of Native American tribes attacked a number of forts in protest of British policies following the French and Indian War. Fort Ligonier was attacked twice and besieged by Indians who were eventually defeated at the Battle of Bushy Run. Three years later the fort, was decommissioned and handed over to a caretaker named Arthur St. Clair. In 1765, the Provost William Smith from the College of Philadelphia declared the importance of the site stating, “The preservation of Fort Ligonier was of the utmost consequence.”

Despite the absence of war the region around Fort Ligonier remained a dangerous one deep into the next decade. In November of 1777 a commissary named Samuel Craig Sr. was summoned to the garrison. While en route he was captured by Indians near an area called Chestnut Ridge. All efforts to locate the man failed, although his horse was found shot dead, surrounded by fragments of torn paper. Craig and his three eldest sons, John, Alexander and Samuel Jr., had served in the Revolutionary War prompting the belief that he had attempted to defend himself against hostiles.

Several acres of the garrison’s property were preserved and the above-ground elements were rebuilt. The inner-fort is 200 square-feet with four bastions, one on each corner. According to the site’s website the fort can be accessed by three gates where “…inside is the officers’ mess, barracks, quartermaster, guardroom, underground magazine, commissary, and officers’ quarters. Immediately outside the fort is General Forbes’s hut. An outer retrenchment, 1,600 feet long, surrounds the fort. Other external buildings include the Pennsylvania hospital (two wards and a surgeon’s hut), a smokehouse, a saw mill, bake ovens, a log dwelling and a forge.”

The transcripts of a journal detailing the fort's construction are available in the Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania. Volume Two, The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania, Fort Ligonier by Clarence M. Busch, State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1896.

Today a museum compliments the fully-restored Fort Ligonier and features a collection of George Washington relics including his saddle pistols, an 11-page memoir on the French and Indian War and a Rembrandt Peale portrait. Washington had served there as a young colonel of the Virginia Regiment in service to the British Crown. A long-term installation titled “The World Ablaze: An Introduction to the Seven Years’ War” is on exhibit there. This unique collection features over 200 British, French and Native American items.

Not much has changed since I first visited Fort Ligonier as a kid. Each year thousands of tourists from all over the world travel to southwestern PA to experience life in the 1700’s. This includes busloads of children who flock to “Ligonier Days” just like I did. I have no doubt that there are plenty of future historians among them guaranteeing that the legacy of this historical gem will be preserved for generations to come. For more information or to plan your trip, visit the Fort Ligonier website.

Wednesday, 23 March 2011

Help Wanted

Many of my fellow historians and bloggers boast a long lineage of American ancestors, some going as far back as the Colonial-era. I know of several individuals with over 6-generations of kin, some who lived in the same state. Many of them are descended from veterans who participated in the Revolutionary and/or Civil War. I do not share their ancestry as relatives on both my father and mother’s immediate side did not settle here until the 1900’s. In fact, I am only a 2nd-generation American as my parent’s parents came over on the boat as children. This has prevented me from becoming anything other than an associate-member of heritage groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Sons of the Revolution.

That said, my grandmother on my mother’s side came to America from England. Her family had lived there for generations so it is quite possible that I have ancestors who participated in the Revolution on the British side. My question is for those of you who know how to research this type of genealogy: How would I even begin to trace someone back to the British ranks? Are there any resources or websites that would provide this kind of information? If I was searching for a soldier in the Civil War I would start by looking for pension papers, but I have no idea where to find data on Redcoats. Does it even exist? I have two last names to go on. Any advice or assistance would be greatly appreciated. Please email me here.

Tuesday, 22 March 2011

The Catholic-Muslim Connection

Baylor University scholar Thomas S. Kidd penned a thought-provoking Op-Ed in the March 10 online edition of The Christian Science Monitor titled Muslim Americans: What would Jesus (or George Washington) do?. In it he draws a parallel between the bigotry that was directed towards Catholics in early America and the angst that is directed towards Muslims today. Frankly, I’ve never made that connection until now. Just as Catholics were once feared by the Protestant majority, Muslims have become, in the minds of many Americans, the great spiritual enemy. This wasn’t always so. In fact, there was a time in America when Muslims were probably more likely to be accepted than Catholics.Following the Protestant Reformation of the 1500’s, a strong movement arose against the Catholic Church of England. Many immigrants brought their own anti-Catholicism beliefs with them to the New World where it eventually became a mainstream point of view. Their prejudices were based on political and theological differences. In 1642, the Colony of Virginia went so far as to enact a law prohibiting Catholics from settling there. A similar proclamation was drafted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The results were a drastic difference between protestant and Catholic settlers. Even "Catholic-friendly" states had remained unbalanced. In 1634, the state of Maryland recorded less than 3,000 Catholics out of a population of 34,000 (around 9% of the population).

Many of the Founding Fathers who preached of liberty and religious freedom distrusted the denomination. Samuel Adams echoed this sentiment stating, “What we have above everything else to fear is Popery.” Thomas Jefferson condemned the Roman Catholic clerics when he wrote, “History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government,” and, “In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own.” John Adams attended a Catholic mass in Philadelphia in 1774 and later ridiculed the rituals practiced by parishioners.

Looking back to those days of intolerance it may be surprising to find that it was General George Washington, a consummate politician, who rose above public opinion to support his Catholic countrymen. Washington was one of the first leaders to be outspoken on the subject of religious bigotry and he took a great risk by voicing an unpopular sentiment. In retrospect this move may have been far more practical than benevolent as Washington no doubt realized that he needed to win the favor of foreign countries that accepted Catholicism, especially France. He also required the service of Catholic military men both domestic and foreign. This included the Marquis de Lafayette, a Catholic Frenchmen who would play a major role in America’s fight for independence.

For years the country’s Englishmen had celebrated “Guy Fawkes Day” also known as “Pope’s Day” on November 5th. The importance of this date commemorated an incident known as “The Gunpowder Plot” in which a Catholic dissident named Guy Fawkes attempted to blow up Parliament in 1605. As part of the festivities, an effigy was burned, depicting the sitting Pope of the Catholic Church. In November of 1775 Washington issued general orders condemning what he called a “ridiculous and childish custom of burning the effigy of the pope.” He added that “American Catholics are among those we ought to consider as brethren embarked on the same cause, the defense of the general liberty of America.” By taking this stand against religious bigotry, Washington appeared both tolerant and diplomatic. This likely helped him to secure the French allies which he desperately needed to win the war. His entire proclamation read:

As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form'd for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope--He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are solliciting, and have really obtain'd, the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defence of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.

Although anti-Catholic sentiment remained in America for some time to come, the official banning of “Pope’s Day” by one of America’s most revered leaders dampened the spirit tremendously. By 1776 the tradition was no longer acknowledged by the masses. This change in public opinion allowed the once ostracized denomination to flourish beside its protestant brethren. Today the Catholic faith makes up almost 24% of the U.S. population with 301 million members.

The nation’s current Muslim citizenship is estimated at approximately 2.6 million, much of which is ostracized like the Catholics of days past. Just as the bloody history of the Crusades blemished the Catholics reputation during colonial times, today’s anti-Muslim sentiments resulted from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Ironically the resulting military actions in the Middle East sent scores of Muslims fleeing the extreme-fundamentalism of their own faith to seek sanctuary in the United States. This mass influx of refugees mirrored that of the earliest Christians who fled from Europe to the New World in order to escape religious persecution. Today the debate remains over the acceptance of Muslim customs and religious practices. This includes the issue of requiring assimilation for nationalization.

Just as early immigrant Catholics were judged on the sins of the crusaders, Muslims in today’s time are often feared to be jihadists. This underlying suspicion has led to a heightened form of prejudice that is often masked behind the guise of vigilance. Perhaps this is no more illustrated than in the recent proposal to add an anti-Shariah amendment into Texas’s constitution. Proponents of the law believe that it is crucial to maintaining the fundamentals of the country, while those who oppose it believe an official denunciation of the Muslim faith by the government to be contrary to the country’s founding principles of “liberty and justice for all.” When examining this argument strictly from a constitutional point of view, it’s not that hard to see both perspectives. Hence the conundrum. Mainstream American-Muslims would certainly never practice such primitive traditions, but the radical-extremists who have hijacked their faith continue to pose a real threat.

This controversial amendment would not be the first time that a clause was instituted to negate a particular religious group. Prior to Washington’s advocacy several states had devised loyalty oaths designed to exclude Catholics from holding state and local office. Yet at the same time Catholics were serving at the Constitutional Convention. This included Thomas Fitzsimons and Daniel Carroll who were delegates from Pennsylvania and Maryland. Both men’s signatures appear on the U.S. Constitution. Carroll had served in the Continental Congress and had signed the Articles of Confederation as well.

Another close comparison between Catholics of the past and Muslims of the present exists in military manpower. Just as Washington’s ranks of the Continental army included Catholic troops, today’s military boasts between 10,000-20,000 Muslims (according to the Department of Defense). The military’s rising requirement for Muslim chaplains is also a testament to the expanding integration of followers of Islam. Ironically, most of the conflicts that the U.S. military is currently engaged in revolve around religious differences between cultures. Muslims are fighting against Muslims on behalf of the U.S. – just as Catholics fought against members of the Catholic Church of England on behalf of their fellow colonists.

To this day religion still remains the great divider. Regardless of one’s spiritual preference, it does us well to recall the sins of our past in order to deal more justly with the present. Only time will tell if the post-traumatic reaction from 9/11 can be healed in the name of unity. Until then we can all gain a unique perspective of what it feels like to be a Muslim by remembering what it once felt like to be a Catholic.

Newer | Latest | Older

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment.

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment. Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places,

Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places,  Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians

Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians