This one's for Jana (again).

This post was deleted when I approved the comments. It appears that the moderator function is not working properly. At the risk of losing another post, I have temporarily turned off the comments option until it is fixed. Here is the repost:

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

This is an extra special thrill for me as I finally get an opportunity to meet and greet a roomful of friends, many who I have known only in the realm of cyberspace. I want to thank Pat and Steve for the invite, as well as the folks here at the Holiday Inn Lexington for thier hospitality. To be invited to give the annual CWHC Muster Banquet address is an exceptional honor, and when you throw in a free meal, well it doesn’t get any better than this. As most of you know I switched over to the era of the Revolution last year and tonight will likely be my last new Civil War talk. As bittersweet as that sounds, I can’t think of a better audience to share it with. I am also very thankful that we get to debut our new documentary film on Richard Kirkland tonight and look forward to your reactions. We are taping this to post online for Pat, Steve and Jana and those who could not be here. Hello friends we miss you. Tonight I hope to share some insights into what I consider to be one of THE most noteworthy and understated campaigns of the entire war.

Over the last few days you have visited the sites and scenes of many of the area’s most hallowed grounds and hallowed halls. You have been to Cross Keys, Port Republic, and New Market. You have visited historic VMI and Lee Chapel. You have no doubt gained a deeper understanding of the participants in the Valley Campaign and their experiences both on and off the battlefield.

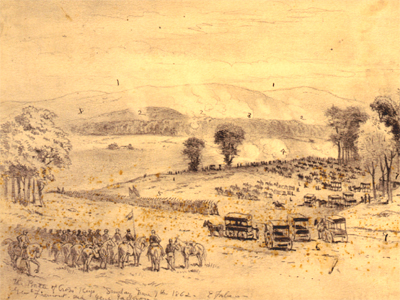

As a result I don’t want to stand up here and regurgitate a bunch of facts that you have learned over the course of this trip. Tonight I want to share something different. I want share some of the lesser known stories from the first Shenandoah Valley Campaign. I will also be using some rare images that may be unknown to you in place of the standard portraits.

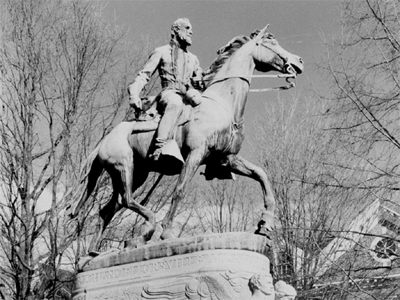

Now I will be the first to admit that my longstanding affection for the life and legacy of Thomas Jackson is perhaps one of the biggest keystones in my foundation as a public historian. My first book was titled Onward Christian Soldier, I taught an 8-week bible study class on Jackson’s piousness at Spotsylvania Presbyterian Church, my license plate says STOWNWL and most recently, the newest member of the Aubrecht brood was named Jackson. OK I like the guy.

That said... I have grown far more critical in my analysis over the years. I like to think that I have matured as a historian and therefore, come to realize that while Thomas Jonathan Jackson was a tremendous leader and an inspiration to those around him, he was not infallible, nor perfect by any stretch of the imagination. He was not a god, he was simply a man. Still worthy of our attention - but not beyond our reach.

Great soldiers, especially great officers, are held in high regards by those who fought under them and this affection influences how their stories were recounted and thus how they are remembered today. Even these titans of military history made mistakes and they are far too often guilty of receiving sole credit for the success of others - albeit unintentionally.

It was while preparing for this speech that I came to realize that as tenacious as Jackson was during his time in the Valley, as many successes he had on the field, he also made mistakes and cost lives. He was stubborn and at times, let his own personal convictions influence his decisions. This was not always in the best interests of his men. Jackson was brilliant, but secretive and this hampered the trust between him and his officers. This revelation of imperfection makes the good general more human in my eyes and in some cases even more worthy of our study.

More importantly, by taking Jackson down off this pedestal, it reinforces the notion that his men were the ones whose blood, sweat, and tears enabled him to rise to such heights. In other words the story of Stonewall in the Valley is much bigger than just Thomas Jackson. Its all about the men. Caesar would not have risen if not for the 13th Legion, nor Washington without the Continental Army, nor Patton without the 3rd.

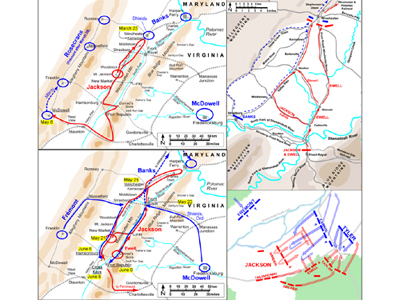

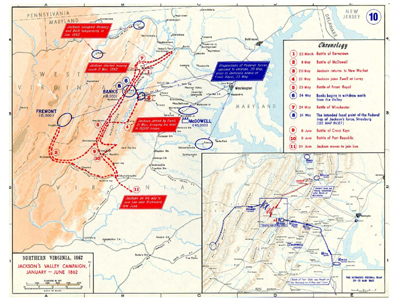

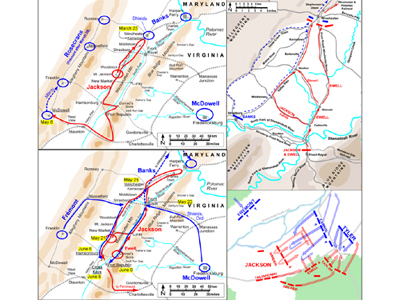

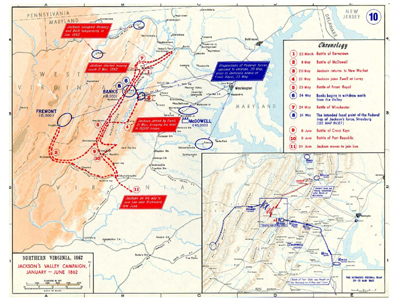

When examining the Valley Campaign of 1862, it is hard not to be immediately struck by the numbers. Let me quote a few from my book: “In May of 1862, Jackson’s troops took part in what is still considered one of the most brilliant and successful missions in American military history, the Shenandoah Valley Campaign. During that time over seventeen thousand Confederates marched more than six hundred miles to participate in four major battles and seven minor engagements. When it was over, Jackson’s troops had defeated four sizable Union armies while capturing nine pieces of artillery, ten thousand small arms and four thousand prisoners.”

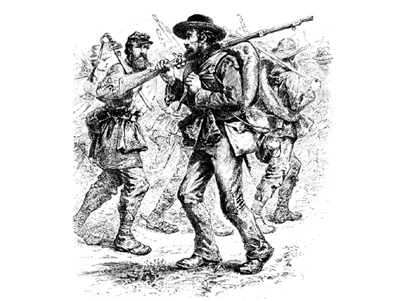

That’s some impressive stats for sure. And it goes without saying that General Jackson was an aggressive commander. His brilliance of strategy and courage on the battlefield were exhibited at every engagement that he participated in from First Manassas to Chancellorsville. Attack–Attack was his tactic of choice. This campaign however, challenged him on a variety of levels. The length and distance at which these fights were spread was extraordinary and the energy that was expended just getting from one fight to another is startling. Maintaining an offensive approach to battle was not always the best directive in the Valley Campaign. Determination and discipline was.

Southern troops marched 646 miles over the course of 48 days. They were also outnumbered by the thousands. Stonewall’s command, the Valley District of the Department of Northern Virginia, started with a force of a mere 5,000, and would eventually peak of 17,000 men. The Union armies (yes that is plural) opposing it numbered at around 52,000 men. So even at its peak, Jackson was lagging behind the enemy by 35,000 men.

Although they would emerge from this campaign victorious, the Confederate forces did not start off that way. The opening battle is still considered to be Jackson’s first and only true defeat of the war. And regardless of who has been blamed over the years, the responsibility ultimately rests with the senior commanding officer.

The Battle of Kernstown was fought on March 23, 1862, in Frederick County and Winchester, Virginia. It was the opening melee and in retrospect remains a perfect example of how poor intelligence and arrogance can doom an army. After being assigned the task of tying down the Federal forces that were in the Shenandoah Valley, Jackson was informed that a small detachment of Northern troops under the command of Colonel Nathan Kimball was ripe for the picking.

Unfortunately for Jackson, this force was not a vulnerable underdog, but a full infantry division that outnumbered his ranks by two to one. His initial tactic was textbook and he sent in his cavalry to instigate an attack. Remember Jackson was a VMI Professor trained at West Point. He may have fought like a lion, but he thought like an officer. Under the command of Turner Ashby, Jackson’s horse soldiers were summarily pressed back. When the general sent a small detachment of infantry in support of his mounted troops, they also failed. At the same time Jackson planned to envelop the enemy with two other brigades. This proved to be a major mistake.

His intentions were based on bad information that had been leaked by southern loyalists and a miscalculation of opposing forces. As a result, Kimble and Col. Erastus Tyler's brigade were able to divide and drive the rebels from the field. In retrospect, exhaustion may have also played a part in this action. Jackson's orders from Johnston were to prevent Union forces from leaving the Valley, which it appeared they were now doing. After receiving word of Kimble’s men, Jackson turned his own men around and, in one of the more grueling forced marches of the war, moved northeast 25 miles on March 22 and another 15 to Kernstown on the morning of March 23. So these guys were literally hiking marathons and going straight into the fight. In the end Union casualties stood at 590 to the Confederate’s 718. Damaged pride and disgruntled officers were also a southern casualty of this engagement.

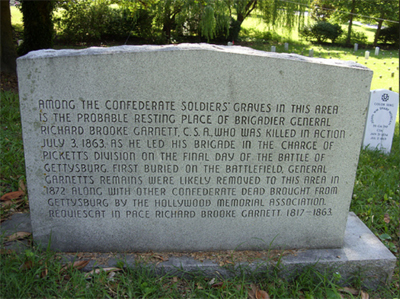

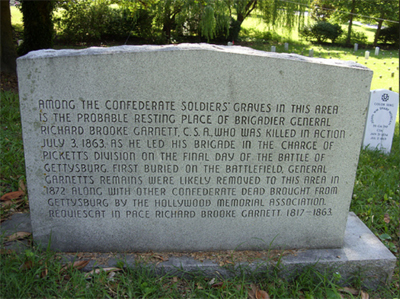

After Kernstown Jackson arrested the commander of his old Stonewall Brigade, Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett, for retreating from the battlefield before permission was received. Garnett would suffer from the humiliation of his court-martial for over a year, until he was finally killed in Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg in July of 1863. Now I know that we are all BIG fans of “THE movie” and the infamous scene in Gettysburg which Garnett rides his horse onto certain death is absolutely true. My personal belief was that he was not only nursing a sore leg, but also trying to save his reputation. This notion makes his demise all the more tragic.

Peter Cozzens, who is the author of a very balanced book on this subject titled Shenandoah 1862, wrote in defense of Garnett and I quote: “Seldom during the Civil War was a general officer as gallant and as capable as Garnett treated so unjustly.... By any objective standard, Garnett had done the best at Kernstown that could reasonably have been expected under the circumstances as they existed. Ignorant of Jackson’s tactical blueprint, his brigade out of ammunition and outflanked, Garnett took the only sane course of action. In doing so he saved the Valley army.”

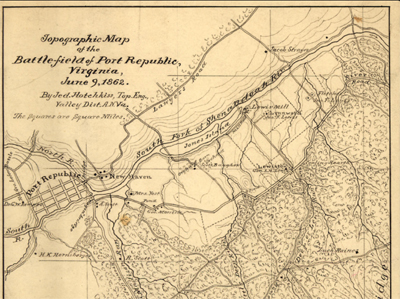

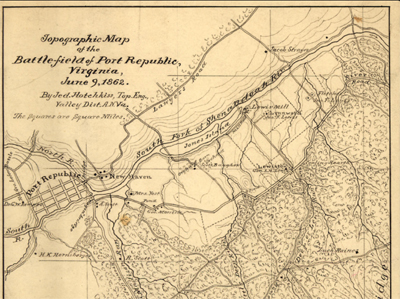

After Kernstown Jackson withdrew his troops to Mount Jackson and this is where I get to talk about the extraordinary work of my favorite unsung hero of the Civil War, Capt. Jedediah Hotchkiss. Jed was an educator and an extremely gifted cartographer and topographer. He was also a northerner by birth. Many people do not know that Hotchkiss was born in Windsor, New York. He graduated from the Windsor Academy and, by the age of 18, he was teaching school in Pennsylvania. In 1855 Hotchkiss and his brother Nelson opened a school in Virginia. So he was a Yankee transplant.

In late March of 1862 Jackson realized that he was ignorant of the landscape that lay before him. The area was too vast and spread out for him to properly direct movement. So he summoned Capt. Hotchkiss and gave him the following orders: “I want you to make me a map of the Valley, from Harpers Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offense and defense.”

According to Jed’s bio: “Running 150 miles in length and 25 miles wide, it was a daunting task, but Hotchkiss accepted the assignment, and worked on the map for the remainder of the war. In order to accommodate his large scale of 6,666.67 feet per inch, he glued together three portions of tracing linen to form a large singe map of 8.25 feet by 3.5 feet, with a three-quarter-inch grid. His map remained unsurpassed in accuracy and detail until the United States Geological Survey published topographical quadrangles later in the nineteenth century.” Now these were more than pretty pictures. Jed’s maps were tactical tools that Jackson exercised profusely. In fact, historians today give Hotchkiss credit for contributing to Jackson’s success in the Valley. I would like to add that Kernstown Battlefield Museum has some excellent examples of his maps that are relevant to this campaign.

Now during this time Gen. Garnett was not the only soldier to be on Jackson’s list. The “Black Knight” himself Turner Ashby was under scrutiny for his poor intelligence gathering prior to Kernstown. His superior removed 10 of his 21 cavalry companies and reassigned them to Charles S. Winder, Garnett's replacement in command of the Stonewall Brigade. Winder mediated between the two officers and the stubborn Jackson uncharacteristically backed down, and restored Ashby's command. Of course like Garnett, Ashby would also be killed in combat. On June 6th Ashby’s men were attacked by the 1st New Jersey Cavalry at Good's Farm near Harrisonburg. Ashby had his horse shot out from under him and as he charged ahead on foot he was shot through the chest and died instantly. Now members of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserve (the Bucktails) took credit for the kill, while others said it was friendly fire. Ironically Ashby had just been promoted to brigadier general 10 days earlier. Ashby’s loss was severe, but of course he would be eclipsed both on the field and in the history books by the cavalier JEB Stuart.

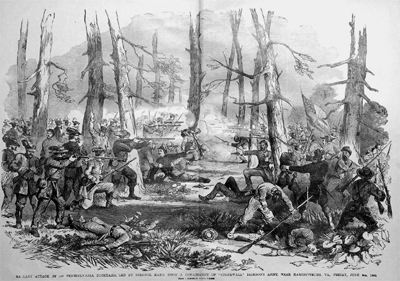

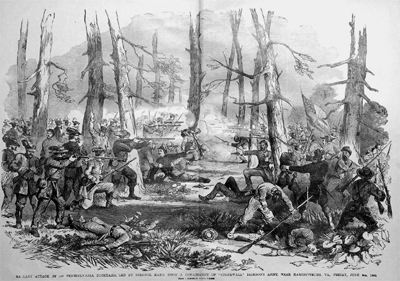

Shortly before the next engagement, the Battle of McDowell, Jackson combined his forces with those of Gen. Allegheny Johnson. When the opposing Union generals realized that they were outnumbered by the 10,000 men that the Confederates commanded, they made a pre-emptive attack. After the first Federal attack was repulsed at a place called Sitlington Hill, the Union troops regrouped made another assault on the Georgia lines. These men were the only non-Virginians on the battlefield.

It is said that they defiantly refused to withdraw in the face of superior numbers. One GA private wrote, “We did not come all this way to Virginia to run before Yankees.” By the end of the day, the 580 Georgians had suffered 180 casualties. This was 3 times more than any other regiment. Union casualties were 259, while the total Confederate losses were 420. It was one of the rare cases in the Civil War where the attacker lost fewer men than the defender.

The next engagement echoed scenes from my favorite John Wayne movie “The Horse Soldiers”. On May 23rd Ashby’s troops forded the Shenandoah River and set out to capture a Union depot and railroad trestle at Buckton Station. After defeating 2 companies of Federal infantry they burned the depot’s structures, tore up railroad track, and cut the telegraph wires, isolating Front Royal. Jackson then marched towards the town.

The center of Jackson’s line of battle was the ferocious Louisiana Tigers battalion (150 men under Ewell’s division), commanded by Col. Wheat. Of course Wheat’s Tigers wore distinctive uniforms similar to the French Zouave. As they attacked the Federals began to retreat and Jackson missed a tremendous opportunity to inflict major damage. His beloved artillery was delayed in arriving and Ashby’s cavalry was late in informing them of Jackson's orders.

That said the retreating Union troops were forced to halt and make a stand at Cedarville. It was there that some of the most lopsided casualties would occur in the entire war. Union casualties were 773, of which 691 were captured. Confederate losses were a mere 36 killed and wounded. Jackson’s men also captured about $300,000 of Federal supplies. The next two battles, one at Winchester and the other at Cross Keys resulted in some of the most insubordinate behavior of the war.

At the battle of Winchester, Jackson’s troops pursued the fleeing Federal forces who were headed south down the Valley Pike. Our friends the Tigers came upon a wagon train and instead of continuing to chase the Yankees, they stopped to loot and pillage the supplies. Jackson had also ordered his cavalry and artillery to move north in order to harass the Union troops on the other side of town, but many of Ashby’s men had found a wagon train of their own and proceeded to get drunk on Federal whiskey.

Jackson was extremely frustrated with the ineffective pursuit and later wrote, “Never was there such a chance for cavalry. Oh that my cavalry was in place!” As a result the Federals fled relatively unimpeded for 35 miles in 14 hours and lived to fight another day. Those two days would come in the form of the battles of Cross Keys and Port Republic with the first fight taking place on June 8th and the next on the 9th.

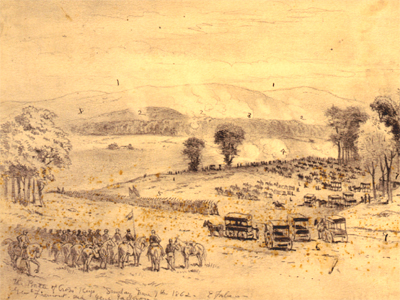

These were the decisive victories in Jackson’s Valley Campaign that ultimately forced the Union armies to retreat while leaving Jackson free to reinforce Gen. Robert E. Lee for the Seven Days Battles outside Richmond. The biggest factor to know about Cross Keys was that the southern troops were outnumbered 11,500 to 5,800 – BUT the northern troops believed the opposite to be true. Therefore they fought cautiously when they likely could have overwhelmed the rebels.

Port Republic was another story and most military historians agree that Jackson had poorly managed this engagement. This makes his victory all the more curious. In failing to properly deploy his men, Port Republic was the most damaging to the Confederates in terms of casualties. They lost 816 against a force one half their size (about 6,000 to 3,500). Union casualties were just over 1,000, with a high percentage representing prisoners. Once again I’d like to call on Historian Peter Cozzens who blames Jackson’s piecemeal deployment of troops for his heavy losses and argues that it was a battle that did not need to have been fought.

Despite this, following the Battle of Port Republic, the Union armies fled the Valley and Stonewall Jackson became the most celebrated soldier in the entire Confederacy. In a classic military campaign of surprise and maneuver, he had accomplished his difficult mission, driving the Yankees from Shenandoah soil and causing Washington to withhold over 40,000 troops from McClellan's offensive.

Military historians Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, summed up Jackson’s success in their study titled How the North Won. They wrote: “Always outnumbered seven to three, every time Jackson engaged he fought with the odds of about four to three in his favor—because, moving rapidly on interior lines, he hit fractions of his enemy with the bulk of his own command. ... Jackson enjoyed the great advantage that the northerners remained widely scattered on a perimeter within which his troops could maneuver to concentrate against first one and then another of the Union forces. Lincoln managed very well, personally maneuvering the scattered Union armies. Since neither Lincoln nor his advisers felt that Jackson’s small force could truly threaten Washington, they chose an offensive response as they sought to exploit their overwhelming forces and exterior position to overwhelm his army. But Jackson's great ability, celerity of movement, and successful series of small fights determined the outcome.” So despite having moments of mediocrity and imperfection, Jackson’s actions were commendable and his reputation as a fierce and uncompromising warrior was validated through this campaign. Southerners everywhere cheered when word arrived that the Yankee invaders had been driven from the Valley. Jackson of course got all the credit and he understandably became a household name. A Confederate Army nurse named Kate Cummings summarized this newfound national love-affair in her diary when she wrote: “A star has arisen: his name [Stonewall], for four weeks he has kept at bay more than one of the boasted armies. He is our protector”

Jackson himself, a devout religious man, gave credit in his own way. At a moment during the final battle in which his buckling troops were saved by reinforcements arriving in the 11th hour, Jackson turned to Ewell and said “General, he who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, sir, blind.”

In May of 1863 Jackson would be accidentally shot by his own men at the Battle of Chancellorsville forever etching his deity-like status in military lore. The 1862 Valley Campaign would go on to become a much studied example of brilliant maneuvering and is now taught at the same military schools in which Jackson attended and taught.

Perhaps the most worthy example of the lasting legacy of Jackson and this campaign comes from Howard Tanner in his excellent book Stonewall in the Valley. This account recalls the bond and memory of the men, who fought and bled together under their beloved commander. They are the ones whose legacy is far too often forgotten.

Tanner writes of an 81-year old man that is lying in his death bed, unconscious and unable to speak. One day there is an unexpected knock at the door and when the son answers it he sees an elderly gentleman standing on the porch. The old man asks to see his ailing father and the son informs him that he is unable to communicate. He says, “It will not be of much comfort to you and none to him.” The visitor interrupted and said “I fought with him at Port Republic. There were 23 of us then and few of us now.” Tanner adds: No more needed to be said. “If any of you wish to see him,” the son added, “You have certainly earned the right to do so.”

It is the bond these men shared that kept alive the enduring legacy of Stonewall in the Valley. They are all equal partners in Jackson’s Journey regardless of rank. And it is our job as historians and enthusiasts to see that they are never forgotten. Thanks to groups like yours - and weekends like this – their stories will remain for future generations. Thank you.

EDITORIAL: Who’s picking up the torch? Nobody.

Crowd gathered for the reenactment of Jefferson Davis's inauguration at the Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, during the Civil War Centennial in 1961. (AL Dept. of Archives and History)

This weekend’s Washington Post featured an outstanding Civil War Sesquicentennial section. The 12-page insert coincided with their Civil War at 150 website and featured a nice blend of articles and polls. Over the last few days, I have recognized multiple copies of this insert casually tossed in garbage cans on the train platform and downtown. Why am I so concerned about garbage? Because this is Fredericksburg! As a result, I am slowly coming to terms with the disinterest by the general public and begrudgingly accepting that none of this really matters to anyone but us.

Regardless of how many great programs our local National Parks Service is planning, the audiences at these events will most likely be made up of the same people that would be attending them anyway. In essence, all the Civil War Sesquicentennial is likely to do is give us ‘buffs’ more things to see. A bad analogy would be extending a special invitation to “Trekees” for a Star Trek Convention. They would still be going otherwise. Another Sesquicentennial lapse will probably take place in the academic realm. Universities across the country are planning a plethora of wonderful ACW programs that will only be frequented by fellow academics. The result is a conference.

Like many of you, I spend a tremendous amount of time leading tours, speaking to groups, and attending ACW-related functions. Most of the time, I am the youngest person in the room and I never-ever see any young people at round tables, museum conferences, or panel chats. Yes, you may see the occasional kid traipsing around a battlefield or participating at a re-enactment with his family, but for the most part, it’s middle-aged folks or older (many seniors or retirees), who still care enough to pursue and cultivate an interest in the Civil War. Many of these enthusiasts were around for the Centennial celebrations of the 1960s and grew up with a penchant for the subject that has blossomed. Unfortunately, times have changed and I predict that this will not happen with the Sesquicentennial. The problem is that there are no fresh faces stepping up to take the places of the old-timers after they are gone. Our audience is thinning everyday and it’s not impossible to see the fading and eventual disappearance of roundtables and historical societies. My generation aka Gen-X, is turning 40 this year and our kids have grown up entirely in the Video Game/Information Age. Civil War memory can’t compete with the Wii and iPhones. Let’s be honest folks, this was never really ‘cool’ to outsiders. We do what we do because we love it (even if no one else gives a damn). Heck, most of my friends and peers consider me to be a geek. They will attend the occasional event out of courtesy, but they don’t have any interest in this subject matter beyond me. My kids hate history. (There are exceptions to the rule. Richard Warren who plays the part of young Richard Kirkland in our film is an example. You may be able to name a few yourself. They are in the vast minority.)

I thought that technology was the issue. I have discussed the idea of using iPads w/ GPS for tours and incorporating 3D animation to present what is no longer there. There are Segway scooter tours going on here in Fredericksburg and many museums are trying to incorporate kid-friendly activities that allow them to touch the exhibits. Guess what? The iPads w/ GPS are too expensive and older people won’t use them. The Segway tours have the same old demographic participating in them, and the local museums are all empty due to the sagging economy. Finally, nobody around here even knows about this. A casual poll during fellowship at my church had three ‘Fred-lifers’ who knew about the Sesquicentennial. My church is in Spotsylvania folks!

As a historian and lifelong enthusiast, I will be very interested to see if there is a surge of interest in Civil War history from the Sesquicentennial. Like you, I will continue to do what I do regardless, and I look forward to attending and participating in as many commemorations as I can. We hope to release the DVD of our documentary “The Angel of Marye’s Heights” in December to recognize the Anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg and kick-off our own Pre- Sesquicentennial celebration.

Still, I hold no false aspirations of the Civil War Sesquicentennial sparking any new interest in young people and extending its current life-expectancy past the existing generation of buffs. IMO, it doesn’t look good. We care. They don't.

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 11:24 AM EST

Updated: Thursday, 11 November 2010 3:00 PM EST

Permalink |

Share This Post

Great Book. Greater Man.

Like many of you, I have been blessed to know some truly amazing people throughout the course of my life. Most of these remarkable individuals have chosen to use their time and talents for the betterment of others. They are generous yet modest, and have an uplifting influence on those lucky enough to be around them.

Like many of you, I have been blessed to know some truly amazing people throughout the course of my life. Most of these remarkable individuals have chosen to use their time and talents for the betterment of others. They are generous yet modest, and have an uplifting influence on those lucky enough to be around them.

I am lucky to know a gentleman who personifies all of these principles and more. Picture the prototypical All-American Alpha-Male, Rock Singer, Football Player, Motorcycle Maniac. Now put him in a wheelchair. For many of us, a productive and fulfilling life would stop there. Not so for this guy. He returned to the stage and became an athlete of epic proportions. He’s also a helluva guy and his positive attitude and motivation rivals that of most people I know, including me. Even his name rings of strength and fortitude and I would bet the farm that his life was unlike that of anyone you have ever met. His name is Attila Domos and his story is extraordinary. I first met Attila back in 1992, a couple years before we moved to Virginia. We have stayed in touch via Facebook and he recently announced the release his first autobiographical book titled “Because You Shouldn't be Afraid to Chase Your Dreams.” The synopsis follows:

Never one to back down in the face of adversity, the name Attila Domos is synonymous with the word “winner.” In the fall of 1993, Domos suffered a falling accident that left him paralyzed at the waist on the same night he and his former rock n’ roll band Big Band Wolf signed a recording contract, but he has never allowed his injury to slow him down. An accomplished musician, athlete, writer and entrepreneur, Domos seems to have his hand in a little bit of everything these days. Go ahead and try to tell him he can’t succeed. That just fuels his competitive fire even more and he will prove you wrong every time. Domos’ steely determination and courage allow him to constantly push himself and his body to the limit in everything he attempts. He has completed numerous self-challenges in an effort to raise money for spinal cord research, including his infamous “Attila vs. the Mountain” hill climb in Pittsburgh. Most recently, he won the 2010 Pittsburgh Marathon’s handcycling division by more than 11 minutes.

Domos’ autobiography entitled, "Because You Shouldn't be Afraid to Chase Your Dreams" touches on his life before, during and after his paralyzing accident. Some events include his childhood as a Hungarian, living in Romania under the ruthless dictator Nicolai Ceausescu, and later his life in a refugee camp. He takes the readers behind the walls of the Vienna Boys Choir, as he became a member of the world famous choir at the age of 10. Readers also get an honest opinion of America through the eyes of a 12 year old immigrant and the struggles that come along with getting accepted by the locals. Attila openly talks about his previous sex/drugs/rock 'n roll lifestyle, life from a wheelchair, his marriage and much, much more. “Because You Shouldn’t be Afraid to Chase Your Dreams” chronicles the extraordinary circumstances and events which shaped Attila into the inspiring man he is today and takes the reader on one man’s improbable journey toward self discovery.

Yeah, that’s ONE guy folks. I’ve always been proud of Attila and I’m even prouder now that he’s joined me in the author ranks and is sharing his story with the world. This incredible book is over 300 pages of insights and inspiration, triumph and tragedy, life, love and more. Attila is exploring traditional print publishing avenues, but he currently has an e-Book version of his bio available for purchase on his website at www.attiladomos.com.

Yeah, that’s ONE guy folks. I’ve always been proud of Attila and I’m even prouder now that he’s joined me in the author ranks and is sharing his story with the world. This incredible book is over 300 pages of insights and inspiration, triumph and tragedy, life, love and more. Attila is exploring traditional print publishing avenues, but he currently has an e-Book version of his bio available for purchase on his website at www.attiladomos.com.

I cannot recommend this book enough and will close this post with a quick story… Attila’s accident occurred about 6 months before my wife and I were married. On the day of our ceremony, he rolled into the reception hall on a walker and stood up when we entered. Next to kissing my wife, that is my favorite memory from that day.

Pre-war race relations at Fredericksburg's landmark churches

With all of the post-election talk about political and racial division in America, I thought it might be a good idea to remind people just how divided we were at one time, and have far we have come together. On March 20th, 2009 I had the privilege of speaking at Manassas Museum. My presentation discussed the split between the whites and blacks attending Fredericksburg Baptist, resulting in Shiloh Baptist (Old Site), as well as the denominational split between the Methodist church over the issue of slavery. This was my first attempt at discussing the issue of racism in the legacy of our town. The transcript of my lecture follows:

INTRODUCTION

Good evening folks. It is an honor and a privilege to have the opportunity to speak to you tonight and I would like to thank each and every one of you for coming. I would also like to thank the entire staff here at the Manassas Museum for their invitation and hospitality. I spoke here back in the fall on "The Great Revival during the War Between the States" and jumped at the chance to return.

Tonight I will be sharing a few excerpts from my book "Houses of the Holy" which tells the stories of the historic churches of Fredericksburg, before, during, and after the Civil War. I'd like to start off with a couple passages from my Introduction:

In order to understand the experiences of the historic churches of Fredericksburg, one must first look at the locality and the important role that organized religion played in the town. Today, the town is known as "America's Most Historic City," while the neighboring county of Spotsylvania is referred to as the "Crossroads of the Civil War." Both are literally saturated with landmark homesteads, museums, plantations and battlefields that draw thousands of tourists each and every year. Churches remain among some of the most coveted attractions for their historical significance and architectural beauty.

Fredericksburg has also been referred to as a "city of churches," as its silhouette is dominated by a plethora of bell towers and steepled roofs. Today there are over three hundred congregations spread throughout the surrounding region. Clearly, anyone walking through the town can see the important role religion played in the day-to-day lives of the town's inhabitants.

The issue of race-relations as well as the debate over the institution of slavery is also a major piece in my book and the subject that I would like to focus on tonight. It's a controversial and unpleasant subject at times, but it plays an important role, not only in the history of these churches, but also in the history of our nation.

Here you see an overhead shot of Old Town today. This is the historic district. Tonight I want to focus on three congregations: Fredericksburg Baptist Church, Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) and Fredericksburg United Methodist Church. The others you see here are also covered extensively in my book. These include St. George's Episcopal Church and the Presbyterian Church of Fredericksburg.

FREDERICKSBURG BAPTIST

First up this evening is Fredericksburg Baptist Church. During the Civil War, this structure suffered extensive damage from Federal artillery fire prior to the city's occupation by Union forces during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Like many area churches, the pews were torn out and the sanctuary was used as a Federal field hospital. Today, the building remains much the way it did after the war damage was repaired.

According to records from the early 1800s, the first “official” Baptist Meeting House (a prelude to a sanctioned house of worship) was established in Fredericksburg around 1803. The original sanctuary and its attendees included whites, slaves and free “Negroes.” Non-white members were required to use side-door entrances and separate seating areas, as the interior space of the sanctuary was racially separated. This trend would continue in churches throughout the South for years to come. Throughout the course of my research I was amazed at how many of Virginia's early churches were integrated. Now, this by no means is what we would consider in modern times to be equality, but it was a sanctioned mixing of the races.

Beginning with a small congregation, Fredericksburg Baptist Church persevered through the years and grew significantly in member numbers. Within a decade of its inauguration, the church boasted over eight hundred attendees on its rolls. Surprisingly, almost three fourths of its membership was made up of slaves and free blacks. This multiracial fellowship represented what may be considered a hypocritical dichotomy, as Christians appeared able to come together on Sundays to celebrate the Sabbath, yet remained separatists during the rest of the week.

Tension between whites and blacks was an inevitable problem as racism and rights for minorities became a highly contested topic of the day. These arguments often pitted whites against whites as abolitionists and slave holders belonged to the same congregation. Denominations themselves often remained benign on the issue in order to appear neutral on the subject. Often this resulted in shared desire to venerate separately.

Fredericksburg Baptist wished to use the split as an opportunity to relocate. At the time the expansion was proposed, there were approximately 625 African-American members in the church's congregation. This group, made up of both free and slave blacks, had been granted permission to attend services on Sunday at the same time as they attended. The inclusion however was a facade and by 1854, tensions began to interfere with worship. Separation appeared to be a foregone conclusion.

A pledge drive was established to assist in financing the construction of a newer and larger building. Despite their limited resources, and given their social situation, the minority members were able to raise an impressive sum of money. In the congregational minutes book that was dated for September 28, 1855, it reads that the congregation's "colored brethren and sisters" pledged $1,100.

BAPTIST SPLIT

It was then determined that the black members would retain the existing building by the riverside, and the white congregation would take all pledges and construct a new building in the center of town. This of course did not sit well with everyone, so a church committee was appointed to oversee the matter. Eventually a compromise of $500 was agreed upon. Here you see the result.

DISMISSAL ROLLS

Upon payment, the deed to the church was transferred. The original membership rolls on file at the Shiloh Baptist outline the legacy of the African-American congregation. In the first column are listed the names of each individual who was received into membership in Nov. and Dec. of 1853. The second column records the date in which each member was baptized into the faith.

The third column shows the month and year when a member was received by letter as a transfer from another church. The fourth column (mostly empty) presents the month and year that a member was reinstated into the church after being previously removed from membership. And the fifth column (which I have highlighted in the box) is the most striking, as it lists the date of "May 4, 1856" over and over as the day in which all of the church's black members were dismissed. This date is significant, as it represents the official split between the races. As the white side of the church "took" the identity of the previously integrated house of worship, the black members were "dismissed" from the official Baptist records.

This in turn enabled the newly formed African-American Baptist congregation to be received into the denomination as a separate body from that of their predecessors. Both churches were then required to draft new constitutions. After they officially gained their own house of worship, they were still not entirely free. Virginia law required the supervision of a white elder, who was tasked with supervising the proceedings.

As was often the case during this period, white Christians took a paternalistic approach to their African-American neighbors that were less rooted in recognition of equality, and more on the guilt-driven, moral obligation to assist those souls held in bondage. This often posed a complex conflict of conscience, as the people offering spiritual nurturing to their "colored brethren" were also slave owners themselves.

That said, I do believe many whites felt that they were truly acting in the best interests of their fellow believers. Charity and compassion is a Christian virtue and despite racial inequality, decency and a sense of common good abounded in the Baptist Church. As a historian I try not to judge people outside of the context of their time and I don't want to sound like I am condemning either side.

I was amazed throughout the course of my research how different the histories of this period were recorded between the white and black congregations. In some cases the recollections were either very different or conflicted one another. I decided to write both sides exactly as they were revealed to me and let them stand on their own merits. This deliberately allows the reader to draw their own conclusions.

SHILOH BAPTIST (OLD SITE)

Shortly after gaining its pseudo independence, the African-American church flourished, building a large membership of both free and slave members. After President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation took effect, the congregation appointed its first black pastor, Reverend George Dixon. When war ended, members who had fled north to Washington DC returned and the church thrived.

Here is an image of the original building that I believe was taken in the 1920's. Despite reaching an agreement over the split, another debate developed regarding the legal requirement of a white pastor shepherding the church.

This concern was addressed in multiple meetings that were recorded. Minutes taken by the white congregation on February of 1856 stated that:

Whereas we desire the colored portion of our church to enjoy the privilege of regular public worship in the house we formerly occupied, therefore, resolved, that the esteemed Brother Elder George Rowe, who has for several months been laboring among them with much acceptance, be requested to continue these labors, and to administer the ordinances of the gospel among them, and also, in conjunction with our pastor, to attend to the order and discipline of the church so long as it may be mutually agreeable to the parties concerned, the colored brethren being expected to make him such compensation for his services as he and they may agree upon.

So not only were the black Baptists required to have a white member supervise their services, they also had to pay him a fee to do so. George Rowe was an elder in the church and owned seven slaves himself. He had established a familiar relationship with the congregation and records indicate that his time there was without problems. By 1858, Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site) was blossoming and its numbers continued to increase. Rowe remained in the position of congregational "overseer" until President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation took effect in early December of 1862.

Unfortunately a few days later, the entire town of Fredericksburg was devastated. This prompted over 300 members to flee north to Washington where they established a daughter church in a large horse stable christened "Shiloh Baptist of Washington DC." This church is still in operation today. Those who remained in town are said to have met sporadically in homes and old warehouses on Fifteenth Street.

It is my personal feeling after reading some of the transcripts of the day that the black citizens simply wanted to manage their own church services and affairs. And that right would eventually come, but certainly not for a long time. In reality, Shiloh Baptist's history was reset so to speak at the end of the Civil War. Only then were they truly able to govern their own affairs and worship as they wished.

FREDERICKSBURG METHODIST

Perhaps no other church in this study was as disrupted by the debate over the institution of secession or slavery as was the Methodists. In fact, differing views over the slave trade would pit members against one another resulting in a full-blown split of the congregation. This denomination was established at a revival event recorded as the "Christmas conference of 1784," at the Lovely Lane Chapel in Baltimore, Maryland.

The result was the official christening of the Methodist Church of America. Almost immediately upon its formation, the ordained superintendents of Methodism began an intensive campaign to spread their new theology across the landscape. Immediately a controversy erupted as the anti-slavery views of some of the church's first preachers did not sit well with many of the South's citizens.

Just a few decades into its existence, the issue of slavery ignited a feud within the congregation itself. The results were drastic to say the least. D.M. Conway published an essay titled: “Fredericksburg First and Last” in the June 1887 issue of the Magazine of American History that explained the results of the conflict. It stated:

While Young Virginia was hastening to the new standard, Old Virginia never tired of its conservatism. But events conspired to make Fredericksburg an especial battle-field of the contending principles. The division of the Methodist Episcopal Church (1844), caused by the suspension of a slave-holding bishop (Andrews), brought conflict into the large congregation at Fredericksburg.

The town was on the border between the Virginia and Baltimore Conferences, while belonging to the latter. The antislavery traditions of Methodism had been once strong enough to suspend from his local ministry the founder of the society, Rev. John Kobler, because he had married a wife (the widow Early) who refused to part with her slaves.

The old Wesleyan testimony now held at Fredericksburg its southmost stronghold, which was defended by powerful preachers (notably the Rev. Norval Wilson) against eloquent champions of the pro-slavery principle, of whom was Rev. Dr. William Smith, sometime President of Randolph Macon College. The pro-slavery elements at length seceded and built a church of their own; and, indeed, it was not until 1865 that the two societies were finally consolidated under the Methodist Church South.

Still, the arguments over slavery in the Old Dominion had been a long-standing debate for almost one hundred years before the Methodists split over it. According to an article printed in an 1887 issue of American History Magazine, “In 1790, Virginia claimed 293,427 registered slaves, which was more than seven times the number in the Northern states combined.” Ironically, it also stated that the Reverend Morgan Godwin of the early English Church was reported to be one of the first clergymen “who ever lifted up his voice against the African slave trade.”

This sentiment most likely came as a great surprise, due to the fact that the proslavery sentiment of many transplanted Englishmen prevented the freeing of Negroes upon the victory of independence. Emancipation continued to be a hotly contested topic among Christians for decades and Virginia remained in the center of the controversy. Many antislavery proponents in Fredericksburg were drawn into a moral dilemma following secession over protecting their land or defending slavery.

Prior to the Civil War, the building housing the Methodist Episcopal church stood as a charming, two-story brick structure located on the south side of Hanover Street, between Prince Edward and Princess Anne Streets. The congregation consisted of approximately 115 white members and 53 black members. In 1848, a large portion of the membership began an exodus, due to the acrimonious debate over slavery. In 1852 they constructed their own meetinghouse (Methodist Episcopal Church South), which was located one block from the parent church. In 1861, the original church rolls listed 164 members, while the new branch boasted 290 followers. Both sites would see significant action during the War Between the States and provide a gruesome service as field hospitals for the occupying Federal forces.

Like all of the neighboring congregations, Fredericksburg Methodist Episcopal Church and its sister parish at Fredericksburg Methodist Episcopal Church South emerged from the Civil War battered, scarred and traumatized. Both the buildings and believers were damaged, physically, mentally and spiritually.

Eventually the George Street branch was absorbed into the Hanover Street Church and the Methodist family of Fredericksburg was finally together again. The reunited church of over two hundred members became part of the Washington District and the Baltimore Conference. Members returned to worship together at the George Street sanctuary and leased the Hanover site to a branch of Episcopalians who had left St. George’s in order to form the Trinity Episcopal Church.

PERSPECTIVES

Understandably, the tragedies and triumphs of the Civil War stuck in the hearts and minds of these church's members. To the white residents who had supported or served in the Confederate cause, the South's loss left them with a bitter feeling of defeat. To the Unionist citizens who had voiced their loyalty in a risky and unpopular arena, the North's victory gave them a sense of bittersweet validation.

Certainly no one appreciated the struggle for independence more than the now-freed African-American citizens. Unfortunately their struggles were far from over. As time passed, wounds were healed, yet there were battles that were still yet to come. Nearly a century later America still struggled over equality and was divided again. In the 1960's efforts to end segregation in the South formed a new civil rights movement that reinvigorated the public in the fight to establish equal rights for blacks. Once again, Fredericksburg weathered the storm and emerged a stronger community.

Today, the city remains a popular tourist attraction. And we residents are so very fortunate to live in a town that others travel across oceans to visit. Ultimately Fredericksburg is also now a unique place memorializing Confederate, Union, and African-American pride. Like Manassas, millions of tourists visit the town whose legacy has been cast in the story of a nation divided. However, after completing my research into the churches of Fredericksburg, I am thoroughly convinced that the real story of Fredericksburg, perhaps even the real story of the nation, is more importantly that of a town reunited.

Race relations have once again come to the forefront of our collective consciousness following the election of our country's first African-American president. This rejuvenation in the examination of race and the relationship between blacks and whites has ignited a new interest in American history.

History remains our area's most valuable commodity and its churches are an important part of this precious heritage. Their steadfast faith demonstrated an enduring legacy of mercy over mayhem and compassion over conflict. Each one stands today as a testament to the human spirit, teaching us through their triumphant stories about the worst and, more importantly, the best of mankind. Thank You.

EXTRA: Our friends from the NPS over at Fredericksburg Remembered have a related post titled A church divided over slavery, and Fredericksburg’s first house of worship for African Americans.

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

Just a reminder that I will be signing books this Saturday at the Gray Ghost Vineyard’s Civil War Author’s Day. Doors open at 11:00 and I will be doing a 20-min talk on “The Life of the Common Confederate Soldier” including a reading of letters detailing the everyday trials and tribulations of camp life at 3:00.

Just a reminder that I will be signing books this Saturday at the Gray Ghost Vineyard’s Civil War Author’s Day. Doors open at 11:00 and I will be doing a 20-min talk on “The Life of the Common Confederate Soldier” including a reading of letters detailing the everyday trials and tribulations of camp life at 3:00.  Like many of you, I have been blessed to know some truly amazing people throughout the course of my life. Most of these remarkable individuals have chosen to use their time and talents for the betterment of others. They are generous yet modest, and have an uplifting influence on those lucky enough to be around them.

Like many of you, I have been blessed to know some truly amazing people throughout the course of my life. Most of these remarkable individuals have chosen to use their time and talents for the betterment of others. They are generous yet modest, and have an uplifting influence on those lucky enough to be around them.  Yeah, that’s ONE guy folks. I’ve always been proud of Attila and I’m even prouder now that he’s joined me in the author ranks and is sharing his story with the world. This incredible book is over 300 pages of insights and inspiration, triumph and tragedy, life, love and more. Attila is exploring traditional print publishing avenues, but he currently has an e-Book version of his bio available for purchase on his website at

Yeah, that’s ONE guy folks. I’ve always been proud of Attila and I’m even prouder now that he’s joined me in the author ranks and is sharing his story with the world. This incredible book is over 300 pages of insights and inspiration, triumph and tragedy, life, love and more. Attila is exploring traditional print publishing avenues, but he currently has an e-Book version of his bio available for purchase on his website at