VAFB speech

Today I received a video of the address that I gave at the Virginia Farm Bureau Women’s Conference. I would like to thank Sherri McKinney, Sr. Producer at the VAFB, for shooting the piece. This 25-min. speech titled “Mary Ball Washington: The Mother of the Father of Our Country” has since then evolved into a 3,000+-word feature that will be running in the July/August issue of Patriots of the American Revolution, as well as a 40-min. presentation that I will be giving in October to the Stafford County Historical Society. This video was shot at the Fredericksburg Hospitality House, on Sunday, March 21, at 7:30 am. I was asked to provide a brief talk that would support the theme of “Past is Present,” and deliver it as a devotional in lieu of the church service that the 350+ attendees would be missing. I didn't have much time to prepare, but I'm fairly happy with how it turned out. Enjoy.

Mary Ball Washington (Part 1) from Michael Aubrecht on Vimeo.

Mary Ball Washington (Part 2) from Michael Aubrecht on Vimeo.

Great stuff

Check out the latest issue of Patriots of the American Revolution as it features an excellent article by my friend and co-author Eric J. Wittenberg on The Battle of Waxhaws A Tragedy in South Carolina. Other great articles include a look at the Bermuda Powder Raid of 1775 by friend Hugh T. Harrington and the Papermakers of Colonial New England by Anne B. Skinner. My feature on Mary Ball Washington will be in the next issue.

Check out the latest issue of Patriots of the American Revolution as it features an excellent article by my friend and co-author Eric J. Wittenberg on The Battle of Waxhaws A Tragedy in South Carolina. Other great articles include a look at the Bermuda Powder Raid of 1775 by friend Hugh T. Harrington and the Papermakers of Colonial New England by Anne B. Skinner. My feature on Mary Ball Washington will be in the next issue.

Hero and Host

ABOVE: A sketch of Weedon's Tavern based on an insurance paper description.

(Sketch by Philip K. Brown, Courtesy of Paula S. Felder, The Free Lance-Star, December 1999)

CORRECTION (Posted 5/1/10): Historian Marian McCabe was kind enough to identify some incorrect data in my post on Weedon’s Tavern and offer the following insights: I noticed that in the section of your blog on Weedon’s Tavern you stated that it was originally built as a home by Charles Washington. Charles Washington’s home, located at 1306 Caroline Street between Fauquier and Hawke Streets, did indeed become a tavern, under a different owner at a later date. In 1792, the house was leased to John Frazier, who named in the Golden Eagle Tavern. In 1821 it was renamed the Rising Sun Tavern by a new tavern operator. In 1827 the building once again became a private residence. It is now owned by Preservation Virginia and is open to the public as the Rising Sun Tavern, a restored 18th century tavern. Weedon’s Tavern (originally Gordon’s) was located at or very near the intersection of Caroline and Amelia Streets – as you noted, “nearly opposite” the town hall and public market, which were located between Caroline and Princess Anne and George and Hanover Streets. Although he had nothing to do with the building itself, Charles Washington was a partner in a butchering business run by George Weedon. Thank you Marian.

A few weeks ago I briefly mentioned a Fredericksburg establishment known as Weedon’s Tavern. This is where Thomas Jefferson met with his political contemporaries in 1777 and agreed to author a bill for spiritual liberties in America. The committee present at Weedon’s was composed of George Mason, George Wythe, Edmund Pendleton and Thomas Ludwell Lee. Jefferson’s declaration of tolerance that followed resulted in the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. This mandate initiated the separation of church and state and is still a part of the Old Dominion’s Constitution. Weedon’s Tavern therefore played a small role in one of the most politically significant events in our nation’s history.

The original structure was built as a home by Charles Washington in 1760 and was later converted into a tavern. It was owned by a subordinate of General George Washington’s named George Weedon, who later became the mayor of Fredericksburg. This was the third inn under Weedon’s management as he had previously run Gordon’s Tavern and the Jockey Races. These colonial hot-spots became regular gathering places for both freemasons and private gentlemen’s clubs. According to a 1999 article by Paula S. Felder in The Free Lance-Star, Weedon’s ledgers (1773-1775) contain over 500 accounts that provide “an invaluable glimpse of people and customs in Fredericksburg during the last years of the colonial era.”

As an experienced military officer, Weedon had served as a Brigadier General in the Continental Army and later in the Virginia Militia. Second in command (and brother-in-law) to Fredericksburg patriot High Mercer, he was present at Trenton, Brandywine, Germantown, Valley Forge, Delaware Crossing and the Yorktown Campaign. Prior to the War for Independence, he served as a Lieutenant under George Washington during the French and Indian War. His service to General Washington however, did not end in the field. In the Diaries of George Washington (Vol. II. 1766-70) the author recorded that:

George Weedon kept a “large and commodious” tavern on the main street of Fredericksburg (now Caroline Street) “nearly opposite” the town hall and public market. Frequented “by the first gentlemen” of Virginia and “neighboring colonies,” it contained “a well accustomed billiard room” and was the place where local horse races were arranged…His fellow Freemasons sometimes adjourned there for food and entertainment after meeting at the town hall…It was a common practice among Virginia gentlemen of this time, when dining or supping at a tavern, to do so in groups either at a private table or, at a large tavern like Weedon’s, in a private room. They would be served as a unit by the innkeeper and then would club for the cost of the food, drink, and room; that is, they would divide the total bill equally. On this evening GW [referring to George Washington] paid 2s. 6d. as his share of the club and lost 15. 6d. at cards.

Despite his post-war popularity as an inn-keeper, not all who had gone off to war with George Weedon held him in the same regards as General Washington. Some of his peers felt him to be far too cautious and demure on the battlefield. This included military equals like the Armand Louis de Gontaut, Duc de Lauzun (later duc de Biron), a French soldier and politician, known for the part he played in the American War of Independence and the French Revolutionary Wars. In The Duc de Lauzun and his Legion, Rochambeau’s most troublesome, colorful soldiers, Robert A. Selig recalls how Lauzun’s memoirs accused Weedon to be at times, far too passive on the battlefield:

Lauzun’s Legion left Lebanon on June 21 and reached White Plains, New York, in early July, But the proposed siege of New York City was too much even for the combined Franco-American army. News of the departure of Admiral de Grasse’s fleet for the Chesapeake Bay caused a change in plans. On August 18, the armies began a march for Virginia. By August 30, the legionnaires were resting at Somerset Court House, and by September 8 they had reached Head of Elk, Maryland.

Here Lauzun and his infantry, 270 men, embarked on boats for the journey down the Chesapeake. The hussars under Vicomte Rene Marie de Darrot, 250 men strong, forded the Susquehanna River at Bald Friar’s Ferry, and advanced south by Baltimore, Georgetown, and Fredericksburg. They crossed the Rappahannock River two miles above Falmouth, and rode on to Williamsburg. There the hussars received orders to reenforce the 1,200 or so militia under Brigadier General George Weedon encamped at Gloucester Courthouse on the north side of the York, where they arrived on the 24th.

Lauzun said in his memoirs that on the previous day a distressed Washington had informed him that “Lord Cornwallis had sent all his cavalry and a considerable body of troops to Gloucester, opposite York,” where they were “watched by a corps of three thousand militiamen under the continental Brigadier-General Weedon.” Lauzun considered Weedon, his senior, “a good enough soldier, but one who hated war, in which he had never wished to engage, and went in deadly fear of coming under fire.”

The commander-in-chief suggested, Lauzun said, that he would tell Weedon that Weedon could have “all the honours” of war but forbid him “to interfere in any way” with Lauzun. Lauzun rejected the arrangement. Once his infantry had disembarked ahead of Rochambeau’s main army near Jamestown on the 23rd, Lauzun set out for Gloucester, where he joined his cavalry on the 28th.

He was determined on “getting on excellently” with his American counterpart. Lauzun could be charming. Rochambeau once described him privately as the “most amiable man in France.” But he also thought that Lauzun was “often the most foolish...who never had enough force of character to be successful.” Weedon, an innkeeper from Fredericksburg who had seen battle more than once, may have been “the best fellow in the world,” whose “one desire was not to interfere in anything.” But he had his pride and saw no reason to defer to a boisterous French aristocrat.

Weedon may have been afraid of the British, but he was not afraid of Lauzun.

Month, or no month, it shouldn't matter.

I had planned to avoid this subject like the plague but an event today changed that... Things have been going surprisingly well after I announced that I was leaving the Civil War era behind and focusing all of my studies on the colonial period. Since shifting subjects I believe I’ve grown immensely as a historian. I feel a renewed sense of vigor for the first time in years and I hope to make a big announcement on my next book project very soon.

I had planned to avoid this subject like the plague but an event today changed that... Things have been going surprisingly well after I announced that I was leaving the Civil War era behind and focusing all of my studies on the colonial period. Since shifting subjects I believe I’ve grown immensely as a historian. I feel a renewed sense of vigor for the first time in years and I hope to make a big announcement on my next book project very soon.

That said, it is completely unrealistic for me to believe that the Civil War will ever be completely removed from my life. I remain vice-chair of the National Civil War Life Foundation, copywriter for artist Mort Kunstler, and co-producer of the upcoming documentary on “The Angel of Marye’s Heights.” I’m also giving a keynote address in Lexington this summer on Jackson’s 1862 Campaign, and will be signing books at events like the Gathering of Eagles and Gray Ghost Winery's Authors Day.

It seems that no matter how much I immerse myself in this new genre, I will always have one foot planted in the 1860’s. Yesterday I personalized a copy of The Southern Cross for Mr. Chuck Rowe, the great-great grandson of Nathan Bedford Forrest and today at church I was handed a folder of primary source material and personal documents from a senior couple who are the descendents of Frederick Alber, an infantryman in Company A of the 17th Michigan. Alber was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for saving a lieutenant on May 12, 1864 during the Battle of Spotsylvania. The couple asked if I would consider writing the story of their great-great grandfather for publication in The Free Lance-Star. They added that they had been turned down for publication years before because he was a Yankee.

Of course I agreed.

In light of all of the arguing that is going on over Confederate History Month, I think it would be quite fitting that an author of five books on the Confederacy would pen a tribute to a Union soldier who has apparently received due-credit in Michigan, but not here in Virginia. So, for the short-time being, I will be taking off the tri-corner hat, dusting off my kepi, and trying to get Frederick Alber some overdue recognition here in Fredericksburg. It is an honor to be asked to do so.

That is what preserving our collective history is all about. Instead of arguing over whose month is whose, we should learn to work together to see that no one's history is forgotten, regardless if there is a month named after it or not. In other words EVERY month should be Confederate History Month, and Union History Month, and African American History Month, etc. We shouldn't need a formal declaration by any government official to care about it.

Now back to our regularly scheduled century...

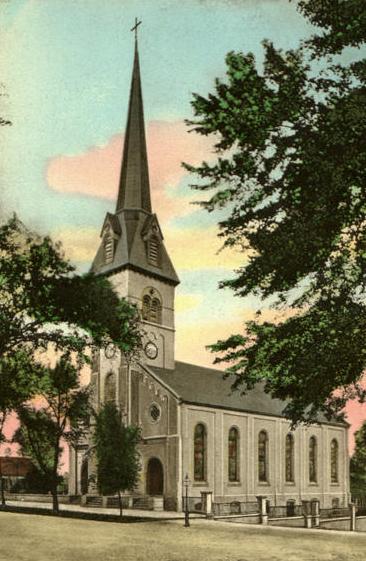

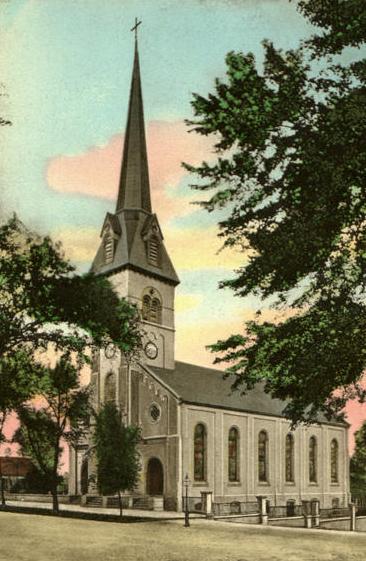

St. George’s Episcopal Church, Fredericksburg, VA

ABOVE: St. George’s Episcopal Church vintage postcard (Published by W.L. Bond, Fredericksburg, VA) Located at the corner of Princess Anne and George Streets, Fredericksburg's original church was built by Colonel Henry Willis in 1732. The current Roman Revival–style structure was built in 1849 and is the third church to be constructed on the premises. Colonel John Spotswood, son of the colonial governor, donated the church’s original bell in 1751. (It was later replaced in 1788 and again in 1856.) The Fredericksburg City Council placed a clock in the bell tower in 1851. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, the church survived many artillery strikes. It also served as a meeting place for the Confederate officers and a hospital for wounded Union soldiers. In 1995, the congregation celebrated its 275th anniversary and continues to function as one of the largest churches in the area. The green spire of St. George’s steeple stands out today as the tallest marker in the city’s skyline.

St. George’s Episcopal Church has several rather unique distinctions that set it apart from the other congregations of Fredericksburg. Foremost, it was the first church that was established at the original settlement of Germanna in 1720 as St. George’s Parish by the House of Burgesses of colonial Virginia. Eight years later, the assembly formally established the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Therefore, St. George’s is the only church in the entire city to be actually mandated by English rule. At the time of its construction, this primitive house of worship was designated to serve the residents of the original frontier port city. As the settlement grew, so did the church.

According to Paula S. Felder’s study, titled Forgotten Companions: The First Settlers of Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburgh Town (With Notes on Early Land Use), the Church of England’s history in Virginia is one fraught with personal conflict. It stated:

The Protestant Reformation which swept Europe in the sixteenth century took a different course in England, principally because of the marital problems of King Henry VIII. Determined to divorce his first wife, who had produced no male heir, Henry sought Papal dispensation to nullify his marriage. His quarrel with the Catholic Church became a jurisdictional conflict in which he sought to assert the authority of the state against the supernational church. In 1533, Parliament passed the Acts of Appeals, which cut the legal ties between the English Church and the Papacy; and in 1534, Henry was declared supreme head of the Church of England, the legally established form of Christianity in England.

The first colonists in Virginia brought with them the canon (church) law of the Established Church as well as the common law of England. As there was no bishop in the colony, the church came under the legislative authority of the General Assembly as early as 1689. Many years later, in 1869, the Bishop of London appointed the Reverend James Blair to serve as his representative or Commissary. Blair became a powerful figure, founder and president of the College of William and Mary. But even in fulfilling his responsibilities for representing the Church, he functioned through secular channels as a member of the Governor’s Council.

Along with the English church came English rules and regulations. Many of the punishments for breaking the covenants of the church were also brought over from England to the New World. This included a myriad of public ridicules and non-lethal tortures, which were used to enforce both civic and congregational codes. The Act of Assembly in 1705 established a strict list of “Religious Offenses” and appropriate punishments. The offenses included: the willful absence from attending church services for over a month; failure to conduct oneself in a decent and orderly manner while in church; participating in any disorderly meeting; gaming or tippling on the Sabbath day; making a casual journey or travel upon the road other than to and from church on the Sabbath; and finally, working in the fields, stores or any other labor calling on the Sabbath.

The punishment for these “crimes” varied from a fine of five shillings or fifty pounds of tobacco for each offense, to ten lashes on the bare back. More serious offenses, such as adultery, were punishable by time in the public stocks and severe fines up to one thousand pounds of tobacco and cask. There was also a rule condemning the act of religious dissention that was drafted in an obscure act of Parliament that was passed in 1689, although it has been recorded that other religious groups may have existed outside of the Church of England at the time.

Historian Robert Beverly discovered accounts of what appeared to be three small Quaker groups and two smaller Presbyterian groups coexisting with St. George’s in 1705. Spotsylvania County court records dated June 1, 1742, present a case in which Henry Brock (religion not provided) had charges against him dismissed after it was proven that he was not a dissenter of the Church of England, but another denomination’s practitioner.

Despite its strict code of conduct and ties back to England, St. George’s prospered and grew into a bustling church in early Virginia. During the colonial period, the church was responsible for the health and welfare of orphans, widows and the sick. It also assisted the poor and downtrodden. As a spiritually educating pillar in the community, St. George’s also established male and female charity schools, as well as Sunday schools for black children.

When the newest church building was constructed, the box pews were sold or rented to the families for a monthly subscription fee. These funds went to cover the cost of the facility as well as day-to-day church operations. The names of many of these original members are still engraved on the pew doors. This resulted in the equivalent of assigned or reserved seating at every service, thus making it fairly easy to keep track of individual member attendance, even in a sanctuary as large as St. George’s.

Throughout the mid- to late 1700s, members and friends of the Washington family begin attending services at St. George’s Church. This included William Paul, brother to America’s father of naval warfare, Commodore John Paul Jones, as well as George Washington’s brother Charles and brother in-law Fielding Lewis, who also served the church as a vestryman. Jones would not be the only congregational member with famous military ties, as blood ancestors of the World War II hero General George Patton also attended the church. Several of them are buried in the adjacent cemetery.

Following the Revolutionary War and victory for America’s independence, the country’s church-state ties were dissolved and the denomination was incorporated into the newly formed Episcopal Church of the United States. Unfortunately, this was not the only war to touch St. George’s, as another fight over independence came knocking at its door, the American Civil War.

Today St. George’s Episcopal Church remains as one of the largest congregations in all of Fredericksburg and it has become a favorite tourist attraction. Although extensive postwar rehabilitation required the patching of over twenty holes made by artillery rounds, the building resumed regular services as early as May of 1865. Since then the church has restored a spectacular forty-six-set pipe organ and installed several priceless Tiffany stained-glass windows.

A major attraction at St. George’s is the colonial-era cemetery that fills the adjacent courtyard. In 1951, church member Carrol H. Quenzel published a directory of the gravesites titled Burials in St. George’s Graveyard. Her book used the inscriptions and notes that were copied by George H.S. King in 1940. Among the noteworthy graves that can be visited today are John Jones (buried in 1752), Anthony and Virginia Patton (relatives of General George S. Patton) and John Coalter (former owner of Chatham Manor). View a complete list at St. George’s Cemetery.

Excerpt from Historic Churches of Fredericksburg: Houses of the Holy by Michael Aubrecht (The History Press, 2008)

Check out the

Check out the  I had planned to avoid this subject like the plague but an event today changed that... Things have been going surprisingly well after I announced that I was leaving the Civil War era behind and focusing all of my studies on the colonial period. Since shifting subjects I believe I’ve grown immensely as a historian. I feel a renewed sense of vigor for the first time in years and I hope to make a big announcement on my next book project very soon.

I had planned to avoid this subject like the plague but an event today changed that... Things have been going surprisingly well after I announced that I was leaving the Civil War era behind and focusing all of my studies on the colonial period. Since shifting subjects I believe I’ve grown immensely as a historian. I feel a renewed sense of vigor for the first time in years and I hope to make a big announcement on my next book project very soon.