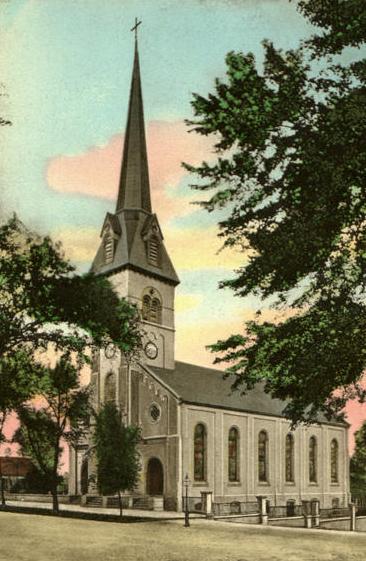

Located at the corner of Princess Anne and George Streets, Fredericksburg's original church was built by Colonel Henry Willis in 1732. The current Roman Revival–style structure was built in 1849 and is the third church to be constructed on the premises. Colonel John Spotswood, son of the colonial governor, donated the church’s original bell in 1751. (It was later replaced in 1788 and again in 1856.) The Fredericksburg City Council placed a clock in the bell tower in 1851. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, the church survived many artillery strikes. It also served as a meeting place for the Confederate officers and a hospital for wounded Union soldiers. In 1995, the congregation celebrated its 275th anniversary and continues to function as one of the largest churches in the area. The green spire of St. George’s steeple stands out today as the tallest marker in the city’s skyline.

St. George’s Episcopal Church has several rather unique distinctions that set it apart from the other congregations of Fredericksburg. Foremost, it was the first church that was established at the original settlement of Germanna in 1720 as St. George’s Parish by the House of Burgesses of colonial Virginia. Eight years later, the assembly formally established the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Therefore, St. George’s is the only church in the entire city to be actually mandated by English rule. At the time of its construction, this primitive house of worship was designated to serve the residents of the original frontier port city. As the settlement grew, so did the church.

According to Paula S. Felder’s study, titled Forgotten Companions: The First Settlers of Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburgh Town (With Notes on Early Land Use), the Church of England’s history in Virginia is one fraught with personal conflict. It stated:

The Protestant Reformation which swept Europe in the sixteenth century took a different course in England, principally because of the marital problems of King Henry VIII. Determined to divorce his first wife, who had produced no male heir, Henry sought Papal dispensation to nullify his marriage. His quarrel with the Catholic Church became a jurisdictional conflict in which he sought to assert the authority of the state against the supernational church. In 1533, Parliament passed the Acts of Appeals, which cut the legal ties between the English Church and the Papacy; and in 1534, Henry was declared supreme head of the Church of England, the legally established form of Christianity in England.

The first colonists in Virginia brought with them the canon (church) law of the Established Church as well as the common law of England. As there was no bishop in the colony, the church came under the legislative authority of the General Assembly as early as 1689. Many years later, in 1869, the Bishop of London appointed the Reverend James Blair to serve as his representative or Commissary. Blair became a powerful figure, founder and president of the College of William and Mary. But even in fulfilling his responsibilities for representing the Church, he functioned through secular channels as a member of the Governor’s Council.

Along with the English church came English rules and regulations. Many of the punishments for breaking the covenants of the church were also brought over from England to the New World. This included a myriad of public ridicules and non-lethal tortures, which were used to enforce both civic and congregational codes. The Act of Assembly in 1705 established a strict list of “Religious Offenses” and appropriate punishments. The offenses included: the willful absence from attending church services for over a month; failure to conduct oneself in a decent and orderly manner while in church; participating in any disorderly meeting; gaming or tippling on the Sabbath day; making a casual journey or travel upon the road other than to and from church on the Sabbath; and finally, working in the fields, stores or any other labor calling on the Sabbath.

The punishment for these “crimes” varied from a fine of five shillings or fifty pounds of tobacco for each offense, to ten lashes on the bare back. More serious offenses, such as adultery, were punishable by time in the public stocks and severe fines up to one thousand pounds of tobacco and cask. There was also a rule condemning the act of religious dissention that was drafted in an obscure act of Parliament that was passed in 1689, although it has been recorded that other religious groups may have existed outside of the Church of England at the time.

Historian Robert Beverly discovered accounts of what appeared to be three small Quaker groups and two smaller Presbyterian groups coexisting with St. George’s in 1705. Spotsylvania County court records dated June 1, 1742, present a case in which Henry Brock (religion not provided) had charges against him dismissed after it was proven that he was not a dissenter of the Church of England, but another denomination’s practitioner.

Despite its strict code of conduct and ties back to England, St. George’s prospered and grew into a bustling church in early Virginia. During the colonial period, the church was responsible for the health and welfare of orphans, widows and the sick. It also assisted the poor and downtrodden. As a spiritually educating pillar in the community, St. George’s also established male and female charity schools, as well as Sunday schools for black children.

When the newest church building was constructed, the box pews were sold or rented to the families for a monthly subscription fee. These funds went to cover the cost of the facility as well as day-to-day church operations. The names of many of these original members are still engraved on the pew doors. This resulted in the equivalent of assigned or reserved seating at every service, thus making it fairly easy to keep track of individual member attendance, even in a sanctuary as large as St. George’s.

Throughout the mid- to late 1700s, members and friends of the Washington family begin attending services at St. George’s Church. This included William Paul, brother to America’s father of naval warfare, Commodore John Paul Jones, as well as George Washington’s brother Charles and brother in-law Fielding Lewis, who also served the church as a vestryman. Jones would not be the only congregational member with famous military ties, as blood ancestors of the World War II hero General George Patton also attended the church. Several of them are buried in the adjacent cemetery.

Following the Revolutionary War and victory for America’s independence, the country’s church-state ties were dissolved and the denomination was incorporated into the newly formed Episcopal Church of the United States. Unfortunately, this was not the only war to touch St. George’s, as another fight over independence came knocking at its door, the American Civil War.

Today St. George’s Episcopal Church remains as one of the largest congregations in all of Fredericksburg and it has become a favorite tourist attraction. Although extensive postwar rehabilitation required the patching of over twenty holes made by artillery rounds, the building resumed regular services as early as May of 1865. Since then the church has restored a spectacular forty-six-set pipe organ and installed several priceless Tiffany stained-glass windows.

A major attraction at St. George’s is the colonial-era cemetery that fills the adjacent courtyard. In 1951, church member Carrol H. Quenzel published a directory of the gravesites titled Burials in St. George’s Graveyard. Her book used the inscriptions and notes that were copied by George H.S. King in 1940. Among the noteworthy graves that can be visited today are John Jones (buried in 1752), Anthony and Virginia Patton (relatives of General George S. Patton) and John Coalter (former owner of Chatham Manor). View a complete list at St. George’s Cemetery.

Excerpt from Historic Churches of Fredericksburg: Houses of the Holy by Michael Aubrecht (The History Press, 2008)

Updated: Friday, 9 April 2010 9:30 AM EDT

Permalink | Share This Post