The truth about Spotsylvania’s Civil War Museum

I would like to take a moment to address an issue that has come to my knowledge today. Several bloggers have commented (here and here) on a couple articles that recently appeared in The Free Lance-Star in regards to the closing and relocation of the Civil War Life Soldier’s Museum here in Spotsylvania. As I am available to speak officially for the National Civil War Life Foundation, I will use my blog to comment.

I would like to take a moment to address an issue that has come to my knowledge today. Several bloggers have commented (here and here) on a couple articles that recently appeared in The Free Lance-Star in regards to the closing and relocation of the Civil War Life Soldier’s Museum here in Spotsylvania. As I am available to speak officially for the National Civil War Life Foundation, I will use my blog to comment.

Although these bloggers are thoughtfully commenting on what they have read online, there is some unintentional misinformation being shared that requires clarity. (I emailed some update info to Kevin Levin, who thankfully brought the blog discussions to my attention, but he has not commented on it yet.) The two FLS articles quoted are located here and here. They may present the notion that the museum and related foundation are severing all ties to Spotsylvania County and moving on to other things. This is incorrect, although there is partial truths in these "changes." Here are the facts:

Yes, Terry Thomann has indeed closed the original Civil War Life Soldier’s Museum in Massaponax and moved his entire gift shop (and a portion of the museums’ collection and attractions) to Old Town Fredericksburg in what used to be the Fredericksburg Historical Prints store. This move took place simply as an economic necessity as the old location was not generating the anticipated business. As the economy continues to suffer, so do historically-themed establishments that rely on tourism. The NCWLF’s Spotsylvania museum venture and Mr. Thomann’s gift shop are two different entities (although they are intertwined as the existing artifact collection belongs to the proprietor of both.)

In order to stay in business, a move was an absolute and when the downtown location became available, Mr. Thomann took it. In retrospect, Terry admits venting some of his frustrations to the first article's reporter and regretfully they made it into the story. The writer was simply quoting what he thought were decisions that had already been made. They were not and Terry has met with individuals from the county and the situation is being discussed en route to being resolved. There is a NCWLF board meeting coming up in a few weeks and I will be sure to update both the media and readers here of new information as it becomes available.

The bottom line is this: The National Civil War Life Foundation is still on the same mission, to build an all-inclusive museum that tells the entire story of the Civil War from all sides. We are still looking at Spotsylvania as a location. We are planning on holding some special events at the new store location to generate additional interest in this project. We are still sponsoring the documentary film on Richard Kirkland that is slated for release in February 2010. We are in talks with Mort Kunstler’s rep about having an exclusive gallery section at both the existing and future locations. We will be updating the website soon to reflect these minor changes that do not affect our mission. And we want to assure all of our supporters that our prime directive remains:

To operate a national museum and research center that preserves and interprets the human story of the American Civil War and connects the lives of all people of that era to the Nation today.

Like many of our area's business owners, Mr. Thomann is doing whatever he has to in order to financially take care of his family. Costs were stacking up and the visitations were dropping. This relocation from a secluded strip-mall in Spotsylvania to Fredericksburg’s main street will hopefully help him fulfill his needs. Our job as a foundation is to stay focused on opening a new museum and we will continue to work hard to accomplish our goal. Once again, this article (and this move) has no bearing on the NCWLF's intent or vision. It simply means that a new gift shop is now open in downtown Fredericksburg with one of the largest inventories in the area. This shop also offers CW artifacts and exhibits, a working tin-type photo studio, and a Civil War in 3D photography show.

Hopefully that can set the record straight for now and the responsive bloggers will caveat their posts. They weren't wrong, they were simply commenting on articles that echoed the emotions of a man who is trying to gain some sense of financial security and provide a service to the community. Any additional questions can be sent to me directly and I will be more than happy to comment (if I can).

Thank you.

Michael Aubrecht

Vice-Chairman, NCWLF

ADDED: Of course I wouldn’t suspect anything less from Mr. Levin who I cordially emailed twice today in an effort to prevent him from spreading misinformation. Beyond apologizing for a recent post that I directed at him then removed, I also tried to explain what was going on as I am an insider. He was kind enough to post this:

Update: This morning I received additional information from a member of the museum’s Board of Directors. For a number of reasons I am not going to include that information since it is so confusing that I can’t make heads or tails of it. One wonders whether this individual even knew about the closing before this morning. I am more than happy to provide a link to an official statement on the museum’s website. It is curious that a statement wasn’t posted before this recent decision was made.

What a class act... YES Kevin, I knew. Once again, you have proven that you are a jerk and I wish you nothing but the best. The very fact that you refuse to reply to my communications or acknowledge or inform your readers of my post-explanation reveals that your own personal dislike of me supersedes any integrity on your blog.

Exclusive Interview

A few years ago I had the pleasure of sharing space at a book signing event with some very generous folks from Ertel Publishing. As a result, I was commissioned to write a couple features for one of their most popular publications, Civil War Historian magazine. Over the next year I penned a lengthy article on baseball during the Civil War that received a lot of acclaim, as well as an intentionally controversial piece in which I ranked the top ten Confederate generals. One of the relationships that blossomed from this commission was a friendship with the editor Benjamin Smith. Ironically, just as my studies have moved further back in our nation’s history, so has Ben’s publishing efforts. Both of us share new interests in the lives and legacies of our Founding Fathers and the revolution that they inspired.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of sharing space at a book signing event with some very generous folks from Ertel Publishing. As a result, I was commissioned to write a couple features for one of their most popular publications, Civil War Historian magazine. Over the next year I penned a lengthy article on baseball during the Civil War that received a lot of acclaim, as well as an intentionally controversial piece in which I ranked the top ten Confederate generals. One of the relationships that blossomed from this commission was a friendship with the editor Benjamin Smith. Ironically, just as my studies have moved further back in our nation’s history, so has Ben’s publishing efforts. Both of us share new interests in the lives and legacies of our Founding Fathers and the revolution that they inspired.

Although I will still continue to support my existing Civil War-era efforts, new projects will likely involve the colonial period. My recent work with The Thomas Jefferson Project for instance has been well-received. A couple weeks ago I accepted an invitation to contribute a feature-length study to Ben’s newest pub-affiliation Patriots of the American Revolution. As a result, I have enthusiastically decided to submit a more detailed and formal study of my look at how slavery is being interpreted at the new Monticello Visitors Center. I also asked Ben if he would be interested in doing a short interview to introduce my readers to what has quickly become one of the most original and informative historical magazines out there. He graciously accepted and our conversation is as follows:

[NOTE: Patriots of the American Revolution is a bi-monthly, full-color, 60-page publication. It is owned by Three Patriots, LLC, and published by Ertel Publishing. Tim Jacobs is its Editor and previous owner; Ben the Associate Editor]

Q: For how long has Patriots of the American Revolution been published? How and why did it begin?

A: The magazine’s editor, Tim Jacobs, started publishing the magazine in 2008. The concept for the publication began out of Tim’s desire to honor his ancestor, Ezekiel Jacobs, who served in the in the Connecticut Militia during the American Revolution. After learning and researching much of Ezekiel’s life and time in the war, Tim wrote an article about him--but couldn’t find a publication to submit the piece. And that was the genesis of Patriots of the American Revolution. Tim wanted to create a venue for people in which they could honor their Patriot ancestors. Today, the magazine still features profiles about people’s Patriot ancestors, but it has grown to include interesting articles about the leaders and battles of the Revolution, as well as research on early American culture.

Q: Explain this growth a little more. For example, how did you get involved?

A: This is where the story about the magazine gets interesting. I’ve been working for Ertel Publishing--a magazine publisher located in Yellow Springs, Ohio—since early 2007. We design and publish several magazines, most of which are somewhat historical in nature. Some of the magazines are owned by Ertel Publishing; some of the magazines are owned by people who hire us to do the design work and assist with editing and marketing. In June of 2008, I came across the magazine’s original website, and thought it might be the perfect sort of magazine for us to design. I called Tim and we hit it off; he and I have a lot in common. So Ertel Publishing started to design Patriots of the American Revolution, and provided Tim with some very basic marketing/PR assistance. The magazine started to grow, but not at the rate that Tim needed it grow by; it’s expensive publishing your own magazine. So in the summer of 2009, three of us here at Ertel Publishing—myself; our General Manager, Vicki McClellan; and our President, Patrick Ertel—formed a company called Three Patriots, LLC and bought the magazine from Tim. However, we kept Tim on as the Editor, and hired Ertel Publishing to continue designing the magazine. That’s when I became Associate Editor.

Q: Has the look or direction of the magazine changed since Three Patriots, LLC purchased it?

A: It has, and quite a bit. The page number has grown from 34 pages to 60 pages, and the magazine is now a bi-monthly publication; it used to be a quarterly. Also, we have added new departments, such as “Culture, Art, & Conflict” and “Allies & Enemies.”

Q: What are some of the other departments that readers can find in each issue?

A: One of our most popular departments is “Notable Bloodlines,” which is written by Tim Jacobs. He traces the family history of a celebrity—such as Ernest Hemingway, or Muhammad Ali—back to the American Revolution, and illuminates the lives and achievements of the celebrity’s Patriot ancestors. We also have a department called “The American Revolution Today,” which focuses on current preservation efforts and historic sites pertaining to the Revolution. Personally, my favorite department is “The American Revolution Month-by-Month.”

Q: What kind of featured articles do you publish?

A: All kinds. Just to give you an idea, I’ll list some of the topics that have appeared in the past two issues: the Battle of Saratoga; the myth of the Jersey Devil; Molly Pitcher; Washington Irving; the Massacre of Cherry Valley; the Turtle submarine; Thomas Paine; and British newspaper coverage of the Battle of Trenton.

Q: What issue are you currently working on?

A: The January/February 2010 issue, which will actually print and ship in the middle of this December.

Q: Can you give readers a sneak peek into what they can expect to see in the upcoming issue?

A: Sure! We have a wonderful article about Betty Zane, a 16-year-old girl who helped Patriots win a battle against British and American Indian soldiers in present-day West Virginia. We also have an article on the so-called Forage War, which occurred in New Jersey during the winter of 1777. Finally, our department called “Culture, Art, & Conflict” focuses on how Loyalists were treated by Patriots during the war. For more information, you’ll just have to check out our website on a regular basis: www.patriotsar.com.

Q: How much is a subscription?

A: The cost is $29.95 for six issues, per year.

Q: Who would you recommend a subscription to?

A: To anyone who likes to read about early American history. We actually cover events from the French and Indian War, through the Revolution, to the War of 1812; all three of those events are connected. Also, I would recommend a subscription to anyone who enjoys the simple art of reading a magazine. I mean, I love blogs. I write a blog for Ertel Publishing, and Tim writes a blog for the magazine. Blogs are incredibly useful and vital. But at the end of a long day, I like to sit at home, put up my feet, and unwind with a magazine. Patriots of the American Revolution is the kind of magazine I would like to decompress with. It’s interesting, educational, well-written, and uses a lot of fine art; it looks nice. Its easy on the eyes. Of course, I am biased!

For more information about Patriots of the American Revolution, please visit www.patriotsar.com.

The Gray Ghost: Mosby in Warrenton, January 18, 1863

Here's the official copy I penned for the latest release from Mort Künstler: Ordering information

Here's the official copy I penned for the latest release from Mort Künstler: Ordering information

Following the Confederate Congress's Partisan Ranger Act of 1862, Major General J.E.B. Stuart appointed one of his most gifted scouts, First Lieutenant John Singleton Mosby, to lead the 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry. "Mosby's Rangers," as they would be called, were formed that following January as the winter of 1863 blanketed the Virginia countryside.

On the 18th of that month, while en route from Fredericksburg to Upper Fauquier, Mosby and fifteen men detached from the 1st Virginia Cavalry stopped off in the town of Warrenton to dine at the renowned Warren-Green Hotel. In November of 1862, Union General George B. McClellan had bid his troops farewell on the steps of this tavern after being relieved of his command by President Abraham Lincoln. This evening however, the Warren-Green witnessed the birth of a new command whose reputation would grow to epic proportions.

This unique group represented twelve native Virginians and three Marylanders who had been handpicked by Mosby himself. They formed the original nucleus of "Mosby's Rangers," and together they would provide intelligence for the Army of Northern Virginia, while also causing disruptions along the Union army supply lines. Their unique ability to evade Federal pursuers earned their commander the nickname of "The Gray Ghost," as he and his troops appeared to vanish whenever they ventured into harm's way.

Mosby himself recalled their unique mission when he wrote, "My purpose was to weaken the armies invading Virginia, by harassing their rear... to destroy supply trains, to break up the means of conveying intelligence, and thus isolating an army from its base, as well as its different corps from each other, to confuse their plans by capturing their dispatches, are the objects of partisan war. It is just as legitimate to fight an enemy in the rear as in the front. The only difference is in the danger."

After the South's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865, Mosby begrudgingly disbanded his rangers, vowing to never surrender formally. He later returned to the town of Warrenton to conduct his law practice and often dined at the Warren-Green Hotel.

Mort Künstler's Comments:

It has been ten years since I last painted the beautiful Warrenton County Courthouse featured in "The Bravest of the Brave." In addition, it has been twelve years since I last painted John Singleton Mosby in "While the Enemy Rests." That is much too long, in my opinion.

I felt it would be wonderful if I could combine both subjects in one painting. Placing Mosby in Warrenton was easy because he operated often out of that area. But there were still a number of obstacles. I wanted to capture a significant moment in his storied career and I also wanted a snow scene. I learned that his first independent command was formed in Warrenton and his original fifteen men stopped off at the Warren-Green Hotel for dinner on January 18, 1863.

By moving my viewpoint around to what is now the Alexandria Pike, I realized that I would not only get a very different angle of the Courthouse from the previous painting, but I could also get the Warren-Green Hotel in the background. I quickly called my good friend and colleague, Dr. James I. Robertson, Jr. and was delighted to learn that it was indeed a bitterly cold windy day that had turned everything white and icy. This gave me my snow scene.

With this newfound knowledge I imagined the difficulties of getting up the hill on the Alexandria Pike, facing the front of the Courthouse. Although they plowed the roads with horse drawn equipment, wagons and carts would have been rendered immobile and abandoned. The trees around the Courthouse today almost obliterate the building from view on Alexandria Pike, so painting the structure accurately was very challenging. Historian Richard Deardoff of Warrenton was of great assistance with research for this painting.

As the men rode up the hill on Court Street alongside the Courthouse, none of them could have imagined the unparalleled success and fame that would subsequently come to the young lieutenant. Mosby himself could not have foreseen the reputation he would gain.

I feel a great sense of satisfaction from this painting, as I was able to combine all of the desired elements into a single image. This includes placing "The Gray Ghost" and his men in front of the Warrenton County Courthouse, on a significant date in their formation, in the beautiful Virginia snow.

This year the paper prints feature the Mosby Heritage Area Association's* seal, which is sure to make it a highly collectible print. *The MAHA's mission is to promote the preservation of the historic, cultural and scenic resources of the Mosby Heritage Area.

Race and remembrance

Yesterday’s trip to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello was a very fruitful day. This was my first time back since August of 2007 and there have been some wonderful additions to the site in my absence. Before I begin with what I hope will be a very original and insightful post, I do have to share three, very important revelations:

Yesterday’s trip to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello was a very fruitful day. This was my first time back since August of 2007 and there have been some wonderful additions to the site in my absence. Before I begin with what I hope will be a very original and insightful post, I do have to share three, very important revelations:

1. Uploading video from your Blackberry while standing on top of a mountain is an exercise in futility.

2. IF you take a photo in the new exhibit hall using a flash, you will set off an alarm (trust me).

3. The new Visitor’s Center is excellent, although I believe there are far less artifacts on display.

Thursday’s expedition had a very important goal, to specifically examine how slavery is now being interpreted and presented at the new Monticello. In one of my essays written for The Jefferson Project, I recalled how I typically glanced over the issue of racism when visiting Jefferson’s home. Today, my eyes have been opened to examining these uncomfortable issues and acknowledging the hypocrisy that existed in the practices of the Founding Fathers. Please note that my respect for this man has not changed, Jefferson was both brilliant and inspiring. The difference is that I now remain in awe of a man who was quite imperfect, just like the rest of us.

My revelation came as I began to take a more critical look at the life and legacy of Thomas Jefferson. Recently I posted here and here on my reading of Gary Wills’ book “Negro President” Jefferson and the Slave Power, as well as The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon-Reed. Admittedly, I had no idea how influential the institution of human bondage was to the establishment and operation of our nation’s earliest federal government. For example, the “three-fifths [slave] clause” of the Constitution tremendously benefited men like Thomas Jefferson and enabled slaveholders to retain high-level political positions for generations.

It was with this newfound perspective that I set out to revisit Jefferson's home. I am aware of some fellow CW bloggers who are re-examining race and memory in regards to the Civil War, but I believe I am the first to take this approach with the newly updated Monticello. My post today looks at four major parts of the visitor’s experience: the visitor’s center and gallery, the house tour, Mulberry Row, and the new guidebook. I took extra special care to record via photo, video, and notes, how slavery was interpreted and presented at each of these venues. (Unfortunately, the video aspect was not successful as I do not believe silent camera pans of displays are worth your time. Therefore I am sticking with the photos and my own observations.)

The objective of this post is to inspire you to visit Monticello just as I did, with a fresh curiosity and newfound perspective. (All photographs were taken on site.)

1. Visitor's Center

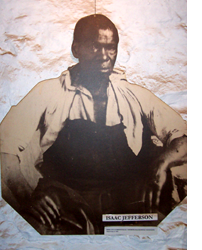

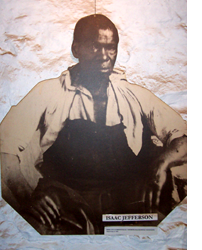

First up is the new Monticello Visitors Center and Smith Education Center. There are two main galleries at this location (along with a theater, café, gift shop, and research library). Both exhibit halls feature specific displays dealing with slavery and the labor force at Monticello. Both sections appear dedicated to recognizing the contributions of the slave community. In the upstairs gallery there is a biography card on Issac Jefferson who had served as a blacksmith, tinsmith, and nailer. You may remember that Issac’s memoirs were recorded by an interviewer and remain among the most insightful narratives about the day-to-day lives of Monticello’s inhabitants. Isaac held a sincere affection for his owner and was reported as saying, “Old Master was very kind to servants.” (For additional quotes see Jefferson at Monticello, Recollections of a Monticello Slave and a Monticello Overseer. Edited by James Adam Bear, Jr.).

First up is the new Monticello Visitors Center and Smith Education Center. There are two main galleries at this location (along with a theater, café, gift shop, and research library). Both exhibit halls feature specific displays dealing with slavery and the labor force at Monticello. Both sections appear dedicated to recognizing the contributions of the slave community. In the upstairs gallery there is a biography card on Issac Jefferson who had served as a blacksmith, tinsmith, and nailer. You may remember that Issac’s memoirs were recorded by an interviewer and remain among the most insightful narratives about the day-to-day lives of Monticello’s inhabitants. Isaac held a sincere affection for his owner and was reported as saying, “Old Master was very kind to servants.” (For additional quotes see Jefferson at Monticello, Recollections of a Monticello Slave and a Monticello Overseer. Edited by James Adam Bear, Jr.).

Next to Issac’s display are matching bios of John Hemings, a tremendously skilled woodworker who crafted much of the interior woodwork of Jefferson’s house at Poplar Forest, as well the most famous of all Monticello’s slaves, Sally Hemings. Of course her relationship with Thomas Jefferson has been the subject of great controversy. According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation’s official statement on the matter: “Although the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings has been for many years, and will surely continue to be, a subject of intense interest to historians and the public, the evidence is not definitive, and the complete story may never be known. The Foundation encourages its visitors and patrons, based on what evidence does exist, to make up their own minds as to the true nature of the relationship.”

This stance continues today in various publications on the matter including the visitor’s handbook (more on that later). In addition to these bio cards, artifacts including some of the slave’s handiwork are on display. The craftsmanship that these men achieved, made even more impressively with the lack of technology, is beyond remarkable. Slave labor at Monticello was definitely skilled labor.

In the downstairs gallery, a large display titled “Those Who Built Monticello” presents the tradesmen, free and enslaved, as well as the tools they used to construct Jefferson’s magnificent estate. According to the plaque, “Jefferson required highly-skilled workmen to realize his vision for Monticello. In Philadelphia in 1798 he engaged James Dinsmore, an Irish house joiner, to take charge of the ongoing construction in his absences. Dinsmore worked closely with enslaved joiner John Hemings to create much of Monticello’s fine woodwork. The team of joiners also included James Oldham (1801-04) and John Neilson (1805-09), and another enslaved man, Lewis...”

In the downstairs gallery, a large display titled “Those Who Built Monticello” presents the tradesmen, free and enslaved, as well as the tools they used to construct Jefferson’s magnificent estate. According to the plaque, “Jefferson required highly-skilled workmen to realize his vision for Monticello. In Philadelphia in 1798 he engaged James Dinsmore, an Irish house joiner, to take charge of the ongoing construction in his absences. Dinsmore worked closely with enslaved joiner John Hemings to create much of Monticello’s fine woodwork. The team of joiners also included James Oldham (1801-04) and John Neilson (1805-09), and another enslaved man, Lewis...”

It continued, “John Hemings, the son of Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings, apprenticed under Dinsmore and hired joiners. He became an accomplished craftsman, succeeded Dinsmore as head joiner in 1809, and trained other slaves in his trade, including his nephews Madison and Eston Hemings. A Monticello overseer recalled that Hemings ‘could make anything that was wanted in woodwork.’ He made fine furniture, a landau carriage, and much of the interior woodwork at Poplar Forest. Jefferson freed Hemings in his will and gave him all the tools of his shop. Continuing to work for the Jefferson family, Hemings lived for several more years at Monticello with his wife, Priscilla.”

2. House and Dependencies Tour

Second in my investigation, the traditional house tour and dependency exhibits. Nothing major has changed noticeably at the top of the hill, although the guided tours are now more open to discussing the institution of slavery and how it was a crucial element in the construction, maintenance and operation of Monticello. Our guide immediately made a point of presenting Jefferson as a typical Virginia plantation owner who had established his lifestyle on the benefits of slave labor. She quoted Jefferson as saying that he abhorred slavery, and believed that he looked at his slaves with a paternalistic view, that they were children who required his supervision. She then countered that notion by saying that dozens of Monticello’s 200 slaves had been traded off by Jefferson and that if one judged him by his deeds and not his words, slavery was something that benefited him greatly. Other than the usual mention of the house staff's chores and showing the dumbwaiters and kitchen carousel, the rest of the tour steered clear of the topic.

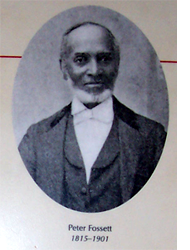

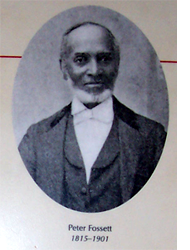

Underneath the house, there were several displays in the center alcove presenting the servant’s quarters, found artifacts, and slave life including that of Issac Jefferson. The kitchen areas in particular presented how Jefferson had his slave cooks trained by French chefs in the traditional dish preparations of the time. Adjacent quarters presented the life of a slave named Joseph Fossett. The plaque reads, “Joseph Fossett (1780-1858) was the grandson of Elizabeth (Betty Hemings) and the son of Mary Hemings Bell, who became free in the 1790s while her son remained a slave at Monticello. According to overseer Edmund Backon, Fossett, a blacksmith, was ‘a very fine workman; could do anything it was necessary to do with steel or iron.’ Joseph and Edith Fossett had ten children, from James, born in the President’s House in 1805, to Jesse, born in 1830. Although Joseph Fossett was freed in Jefferson’s will, his wife and children were sold at the Monticello estate auction in 1827. He continued to work as a blacksmith and, with the help of his mother and other free family members, was able to purchase the freedom of Edith and some of their children. They moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in the 1840s. In 1850 their son Peter, who left a number of recollections of his life, became free and joined his family in Cincinnati, where he was a prominent caterer and Baptist minister.”

Underneath the house, there were several displays in the center alcove presenting the servant’s quarters, found artifacts, and slave life including that of Issac Jefferson. The kitchen areas in particular presented how Jefferson had his slave cooks trained by French chefs in the traditional dish preparations of the time. Adjacent quarters presented the life of a slave named Joseph Fossett. The plaque reads, “Joseph Fossett (1780-1858) was the grandson of Elizabeth (Betty Hemings) and the son of Mary Hemings Bell, who became free in the 1790s while her son remained a slave at Monticello. According to overseer Edmund Backon, Fossett, a blacksmith, was ‘a very fine workman; could do anything it was necessary to do with steel or iron.’ Joseph and Edith Fossett had ten children, from James, born in the President’s House in 1805, to Jesse, born in 1830. Although Joseph Fossett was freed in Jefferson’s will, his wife and children were sold at the Monticello estate auction in 1827. He continued to work as a blacksmith and, with the help of his mother and other free family members, was able to purchase the freedom of Edith and some of their children. They moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in the 1840s. In 1850 their son Peter, who left a number of recollections of his life, became free and joined his family in Cincinnati, where he was a prominent caterer and Baptist minister.”

3. Mulberry Row

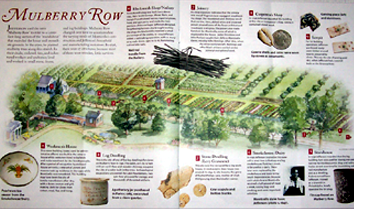

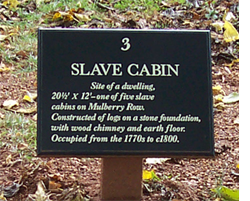

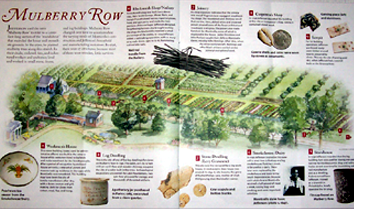

Third and perhaps the most direct display of slave life at Monticello is the stops along Mulberry Row. In addition to traditional placards, brick ruins mark the areas of significance. Named for the mulberry trees planted along it, Mulberry Row was the center of plantation activity at Monticello from the 1770s to Jefferson’s death in 1826. Five log dwellings for slaves were located on Mulberry Row in 1796. The Mulberry Row cabins were occupied mainly by household servants -- women who did the cooking, washing, house cleaning, sewing, and child tending. According to Monticello’s website, “Not all slaves lived on Mulberry Row. A small number who were household servants lived in rooms in the basement-level dependency wings of Monticello, and others lived in cabins located elsewhere at Monticello and outlying farms.”

Stops along the way include slave dwellings, workman’s house, storehouse, blacksmith shop, nailery and a joinery. Some people may not be aware that all building materials including Monticello’s bricks and nails were made on site. I was surprised to learn that white workers also lived along this section of the estate. The T.J. Foundation states that, “A blacksmith shop was built on this site about 1793. Here Jefferson’s slaves Little George, Moses, and Joe Fossett shoed horses, repaired the metal parts of plows and hoes, replaced gun parts, and made the iron portions of the carriages that Jefferson designed. Neighboring farmers brought work to the shop as well, and the slave blacksmiths were given a percentage of the profits of their labor. In 1794, Jefferson added a nailmaking operation to the shop, in an effort to provide an additional source of income. Nailrod was shipped to Monticello by water from Philadelphia and was hammered into nails by as many as fourteen young male slaves, aged ten to sixteen.”

Stops along the way include slave dwellings, workman’s house, storehouse, blacksmith shop, nailery and a joinery. Some people may not be aware that all building materials including Monticello’s bricks and nails were made on site. I was surprised to learn that white workers also lived along this section of the estate. The T.J. Foundation states that, “A blacksmith shop was built on this site about 1793. Here Jefferson’s slaves Little George, Moses, and Joe Fossett shoed horses, repaired the metal parts of plows and hoes, replaced gun parts, and made the iron portions of the carriages that Jefferson designed. Neighboring farmers brought work to the shop as well, and the slave blacksmiths were given a percentage of the profits of their labor. In 1794, Jefferson added a nailmaking operation to the shop, in an effort to provide an additional source of income. Nailrod was shipped to Monticello by water from Philadelphia and was hammered into nails by as many as fourteen young male slaves, aged ten to sixteen.”

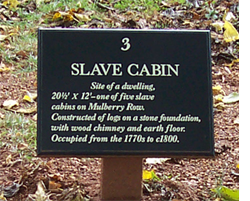

The crumbled foundation remains of a typical Mulberry Row slave cabin. According to the plaque, the structures were approximately 20 ft. x 12 ft., constructed of logs on a stone foundation, with a wood chimney and earth floor. These buildings overlooked the main produce gardens. Today there is a special Plantation Tour available that covers the slave community and its daily contribution in more detail. Mulberry Row is a main focal point of the walking tour.

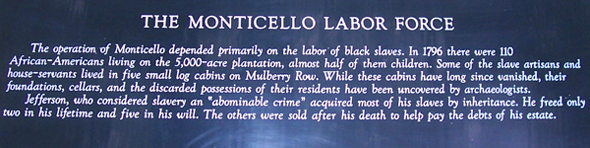

(Excerpt: In 1796 there were 110 African-Americans living on the 5,000-acre plantation, almost half of them children.)

4. Monticello Visitor's Guidebook

Fourth and finally, my attentions were drawn to the newly updated Monticello Visitor’s Guide. I always save my brochures, maps and handouts when touring historical sites and was able to refer back to the old version. I also had a children’s handout from 2007 which I have always been curious about. The illustrations that explain to children the day-to-day life at Monticello depict slaves happily cooking in the kitchen and playing with the Jefferson children around the fish pond. No doubt slave-master relationships like this existed, but these representations seemed a little too “happy-go-lucky” for my tastes. Of course little children are far too young to understand or comprehend the issues of slavery, but these candy-coated drawings were over the top.

The new Monticello guidebook features two large spreads dealing with slave labor. The first is titled “Mulberry Row” and includes an illustrated map of the grounds and photographs of artifacts. Once again Issac Jefferson makes an appearance (clearly the most exhibited slave on the premises). A section on the Storehouse states, “In 1796 Jefferson recorded that the log building here was used for storing iron and nail rod for the blacksmith shop and nailery. It also served over time for tinsmithing and nail manufacture and as a dwelling. A slave named Issac Jefferson, trained as a tinsmith in Philadelphia, briefly operated the tin shop.”

The new Monticello guidebook features two large spreads dealing with slave labor. The first is titled “Mulberry Row” and includes an illustrated map of the grounds and photographs of artifacts. Once again Issac Jefferson makes an appearance (clearly the most exhibited slave on the premises). A section on the Storehouse states, “In 1796 Jefferson recorded that the log building here was used for storing iron and nail rod for the blacksmith shop and nailery. It also served over time for tinsmithing and nail manufacture and as a dwelling. A slave named Issac Jefferson, trained as a tinsmith in Philadelphia, briefly operated the tin shop.”

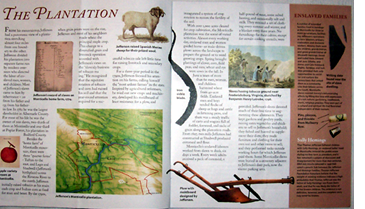

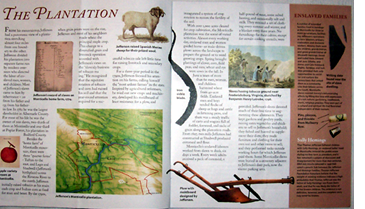

The second spread is titled “The Plantation” and deals specifically with the institution of slavery. It states, “Most of Jefferson’s slaves came to him by inheritance – 20 from his father and 135 from his father-in-law. In 1782, he was the largest slaveholder in Albemarle County. For most of his life he was the owner of 200 slaves, two-thirds of them at Monticello and one-third at Poplar Forest, his plantation in Bedford County.” A photograph of Jefferson’s record of slaves compliments the copy and a sidebar deals directly with the subjects of enslaved families and Sally Hemings. Both of these are new additions and bear quoting here:

The second spread is titled “The Plantation” and deals specifically with the institution of slavery. It states, “Most of Jefferson’s slaves came to him by inheritance – 20 from his father and 135 from his father-in-law. In 1782, he was the largest slaveholder in Albemarle County. For most of his life he was the owner of 200 slaves, two-thirds of them at Monticello and one-third at Poplar Forest, his plantation in Bedford County.” A photograph of Jefferson’s record of slaves compliments the copy and a sidebar deals directly with the subjects of enslaved families and Sally Hemings. Both of these are new additions and bear quoting here: “Enslaved Families: A number of extended families lived in bondage at Monticello for three or more generations, facilitating Jefferson’s operations as farm laborers, artisans, tradesmen and domestic workers. Among them were the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of Elizabeth Hemings, David and Isabel Hern, Edward and Jane Gillette, and James and Cate Hubbard. Nights, Sundays, and holidays provided the only opportunities to socialize and nurture their connections that united them as a community. Like their fellows across the South, Monticello slaves resisted slavery’s dehumanizing effects by filling this time with expressions of a rich culture: gardening, needlework, music, religious practice. They were part of a cultural and spiritual life that flourished independent of their masters.”

“Sally Hemings: That Thomas Jefferson fathered children with Sally Hemings, an enslaved ladies’ maid at Monticello, entered the public arena during his first term as president, and it has remained a subject of discussion and disagreement for more than two centuries. DNA tests results released in 1998 indicated a genetic link between the Jefferson and Hemings families. Thomas Jefferson Foundation historians believe that the weight of existing evidence indicates a high probability that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’ son Eston (born 1808), and that he was likely the father of all her known children. The evidence is not definitive, however, and the complete story may never be known.” (Our friend Richard Williams recently posted some thoughts on his blog about a book by William G. Hyland Jr. titled In Defense of Thomas Jefferson: The Sally Hemings Sex Scandal, which takes the opposite stance.)

I have to admit that this trip to Monticello yielded a variety of different conclusions for me. The Thomas Jefferson that I recognize today was a man who may very well have held a sincere paternalistic fondness for his slaves, but at the same time, he held them in the chains of bondage. Despite the fact that many of his servants received specialized training and developed trades that resulted in the creation of great things, they were simultaneously denied the basic principle of freedom. This is where the contradiction of the man who penned the Declaration of Independence lies. Thomas Jefferson was an extraordinary man whose contributions to this country cannot be denied, but he was also a man who held racist views of the period. This is an undeniable truth.

I have to admit that this trip to Monticello yielded a variety of different conclusions for me. The Thomas Jefferson that I recognize today was a man who may very well have held a sincere paternalistic fondness for his slaves, but at the same time, he held them in the chains of bondage. Despite the fact that many of his servants received specialized training and developed trades that resulted in the creation of great things, they were simultaneously denied the basic principle of freedom. This is where the contradiction of the man who penned the Declaration of Independence lies. Thomas Jefferson was an extraordinary man whose contributions to this country cannot be denied, but he was also a man who held racist views of the period. This is an undeniable truth.

Thankfully, the folks at Monticello are not shying away from this aspect of Jefferson’s life and the Foundation has made great strides to include an African-American presence in their presentation. It not only fills a void of far too neglected history, it also makes Thomas Jefferson human. Try to keep this in mind the next time that you visit Monticello and see if you too leave with a broader understanding of this remarkable, yet flawed Founding Father.

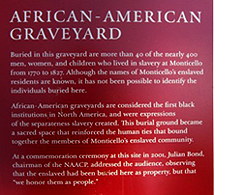

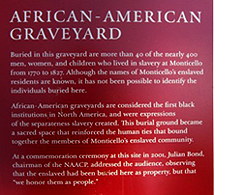

UPDATE: One additional area that fits the attention of this study is the African-American graveyard that is located on the grounds of the estate. According to the sign, this cemetery is the final resting place of 40+ blacks who lived in slavery at Monticello from 1770-1827. It adds that although the names of Jefferson's slaves were known, it has not been possible to identify any of those buried here. This is perhaps one of the most telling of all the exhibits as a separate burial plot personified the society of segregation that even in death, existed at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.

UPDATE: One additional area that fits the attention of this study is the African-American graveyard that is located on the grounds of the estate. According to the sign, this cemetery is the final resting place of 40+ blacks who lived in slavery at Monticello from 1770-1827. It adds that although the names of Jefferson's slaves were known, it has not been possible to identify any of those buried here. This is perhaps one of the most telling of all the exhibits as a separate burial plot personified the society of segregation that even in death, existed at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.

I would like to take a moment to address an issue that has come to my knowledge today. Several bloggers have commented (here and here) on a couple articles that recently appeared in The Free Lance-Star in regards to the closing and relocation of the Civil War Life Soldier’s Museum here in Spotsylvania. As I am available to speak officially for the National Civil War Life Foundation, I will use my blog to comment.

I would like to take a moment to address an issue that has come to my knowledge today. Several bloggers have commented (here and here) on a couple articles that recently appeared in The Free Lance-Star in regards to the closing and relocation of the Civil War Life Soldier’s Museum here in Spotsylvania. As I am available to speak officially for the National Civil War Life Foundation, I will use my blog to comment.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of sharing space at a book signing event with some very generous folks from Ertel Publishing. As a result, I was commissioned to write a couple features for one of their most popular publications, Civil War Historian magazine. Over the next year I penned a lengthy article on baseball during the Civil War that received a lot of acclaim, as well as an intentionally controversial piece in which I ranked the top ten Confederate generals. One of the relationships that blossomed from this commission was a friendship with the editor Benjamin Smith. Ironically, just as my studies have moved further back in our nation’s history, so has Ben’s publishing efforts. Both of us share new interests in the lives and legacies of our Founding Fathers and the revolution that they inspired.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of sharing space at a book signing event with some very generous folks from Ertel Publishing. As a result, I was commissioned to write a couple features for one of their most popular publications, Civil War Historian magazine. Over the next year I penned a lengthy article on baseball during the Civil War that received a lot of acclaim, as well as an intentionally controversial piece in which I ranked the top ten Confederate generals. One of the relationships that blossomed from this commission was a friendship with the editor Benjamin Smith. Ironically, just as my studies have moved further back in our nation’s history, so has Ben’s publishing efforts. Both of us share new interests in the lives and legacies of our Founding Fathers and the revolution that they inspired.  Here's the official copy I penned for the latest release from Mort Künstler:

Here's the official copy I penned for the latest release from Mort Künstler:  Yesterday’s trip to

Yesterday’s trip to  First up is the new Monticello Visitors Center and Smith Education Center. There are two main galleries at this location (along with a theater, café, gift shop, and research library). Both exhibit halls feature specific displays dealing with slavery and the labor force at Monticello. Both sections appear dedicated to recognizing the contributions of the slave community. In the upstairs gallery there is a biography card on Issac Jefferson who had served as a blacksmith, tinsmith, and nailer. You may remember that Issac’s memoirs were recorded by an interviewer and remain among the most insightful narratives about the day-to-day lives of Monticello’s inhabitants. Isaac held a sincere affection for his owner and was reported as saying, “Old Master was very kind to servants.” (For additional quotes see Jefferson at Monticello, Recollections of a Monticello Slave and a Monticello Overseer. Edited by James Adam Bear, Jr.).

First up is the new Monticello Visitors Center and Smith Education Center. There are two main galleries at this location (along with a theater, café, gift shop, and research library). Both exhibit halls feature specific displays dealing with slavery and the labor force at Monticello. Both sections appear dedicated to recognizing the contributions of the slave community. In the upstairs gallery there is a biography card on Issac Jefferson who had served as a blacksmith, tinsmith, and nailer. You may remember that Issac’s memoirs were recorded by an interviewer and remain among the most insightful narratives about the day-to-day lives of Monticello’s inhabitants. Isaac held a sincere affection for his owner and was reported as saying, “Old Master was very kind to servants.” (For additional quotes see Jefferson at Monticello, Recollections of a Monticello Slave and a Monticello Overseer. Edited by James Adam Bear, Jr.). In the downstairs gallery, a large display titled “Those Who Built Monticello” presents the tradesmen, free and enslaved, as well as the tools they used to construct Jefferson’s magnificent estate. According to the plaque, “Jefferson required highly-skilled workmen to realize his vision for Monticello. In Philadelphia in 1798 he engaged James Dinsmore, an Irish house joiner, to take charge of the ongoing construction in his absences. Dinsmore worked closely with enslaved joiner John Hemings to create much of Monticello’s fine woodwork. The team of joiners also included James Oldham (1801-04) and John Neilson (1805-09), and another enslaved man, Lewis...”

In the downstairs gallery, a large display titled “Those Who Built Monticello” presents the tradesmen, free and enslaved, as well as the tools they used to construct Jefferson’s magnificent estate. According to the plaque, “Jefferson required highly-skilled workmen to realize his vision for Monticello. In Philadelphia in 1798 he engaged James Dinsmore, an Irish house joiner, to take charge of the ongoing construction in his absences. Dinsmore worked closely with enslaved joiner John Hemings to create much of Monticello’s fine woodwork. The team of joiners also included James Oldham (1801-04) and John Neilson (1805-09), and another enslaved man, Lewis...”  Underneath the house, there were several displays in the center alcove presenting the servant’s quarters, found artifacts, and slave life including that of Issac Jefferson. The kitchen areas in particular presented how Jefferson had his slave cooks trained by French chefs in the traditional dish preparations of the time. Adjacent quarters presented the life of a slave named Joseph Fossett. The plaque reads, “Joseph Fossett (1780-1858) was the grandson of Elizabeth (Betty Hemings) and the son of Mary Hemings Bell, who became free in the 1790s while her son remained a slave at Monticello. According to overseer Edmund Backon, Fossett, a blacksmith, was ‘a very fine workman; could do anything it was necessary to do with steel or iron.’ Joseph and Edith Fossett had ten children, from James, born in the President’s House in 1805, to Jesse, born in 1830. Although Joseph Fossett was freed in Jefferson’s will, his wife and children were sold at the Monticello estate auction in 1827. He continued to work as a blacksmith and, with the help of his mother and other free family members, was able to purchase the freedom of Edith and some of their children. They moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in the 1840s. In 1850 their son Peter, who left a number of recollections of his life, became free and joined his family in Cincinnati, where he was a prominent caterer and Baptist minister.”

Underneath the house, there were several displays in the center alcove presenting the servant’s quarters, found artifacts, and slave life including that of Issac Jefferson. The kitchen areas in particular presented how Jefferson had his slave cooks trained by French chefs in the traditional dish preparations of the time. Adjacent quarters presented the life of a slave named Joseph Fossett. The plaque reads, “Joseph Fossett (1780-1858) was the grandson of Elizabeth (Betty Hemings) and the son of Mary Hemings Bell, who became free in the 1790s while her son remained a slave at Monticello. According to overseer Edmund Backon, Fossett, a blacksmith, was ‘a very fine workman; could do anything it was necessary to do with steel or iron.’ Joseph and Edith Fossett had ten children, from James, born in the President’s House in 1805, to Jesse, born in 1830. Although Joseph Fossett was freed in Jefferson’s will, his wife and children were sold at the Monticello estate auction in 1827. He continued to work as a blacksmith and, with the help of his mother and other free family members, was able to purchase the freedom of Edith and some of their children. They moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in the 1840s. In 1850 their son Peter, who left a number of recollections of his life, became free and joined his family in Cincinnati, where he was a prominent caterer and Baptist minister.” Stops along the way include slave dwellings, workman’s house, storehouse, blacksmith shop, nailery and a joinery. Some people may not be aware that all building materials including Monticello’s bricks and nails were made on site. I was surprised to learn that white workers also lived along this section of the estate. The T.J. Foundation states that, “A blacksmith shop was built on this site about 1793. Here Jefferson’s slaves Little George, Moses, and Joe Fossett shoed horses, repaired the metal parts of plows and hoes, replaced gun parts, and made the iron portions of the carriages that Jefferson designed. Neighboring farmers brought work to the shop as well, and the slave blacksmiths were given a percentage of the profits of their labor. In 1794, Jefferson added a nailmaking operation to the shop, in an effort to provide an additional source of income. Nailrod was shipped to Monticello by water from Philadelphia and was hammered into nails by as many as fourteen young male slaves, aged ten to sixteen.”

Stops along the way include slave dwellings, workman’s house, storehouse, blacksmith shop, nailery and a joinery. Some people may not be aware that all building materials including Monticello’s bricks and nails were made on site. I was surprised to learn that white workers also lived along this section of the estate. The T.J. Foundation states that, “A blacksmith shop was built on this site about 1793. Here Jefferson’s slaves Little George, Moses, and Joe Fossett shoed horses, repaired the metal parts of plows and hoes, replaced gun parts, and made the iron portions of the carriages that Jefferson designed. Neighboring farmers brought work to the shop as well, and the slave blacksmiths were given a percentage of the profits of their labor. In 1794, Jefferson added a nailmaking operation to the shop, in an effort to provide an additional source of income. Nailrod was shipped to Monticello by water from Philadelphia and was hammered into nails by as many as fourteen young male slaves, aged ten to sixteen.”

The new Monticello guidebook features two large spreads dealing with slave labor. The first is titled “Mulberry Row” and includes an illustrated map of the grounds and photographs of artifacts. Once again Issac Jefferson makes an appearance (clearly the most exhibited slave on the premises). A section on the Storehouse states, “In 1796 Jefferson recorded that the log building here was used for storing iron and nail rod for the blacksmith shop and nailery. It also served over time for tinsmithing and nail manufacture and as a dwelling. A slave named Issac Jefferson, trained as a tinsmith in Philadelphia, briefly operated the tin shop.”

The new Monticello guidebook features two large spreads dealing with slave labor. The first is titled “Mulberry Row” and includes an illustrated map of the grounds and photographs of artifacts. Once again Issac Jefferson makes an appearance (clearly the most exhibited slave on the premises). A section on the Storehouse states, “In 1796 Jefferson recorded that the log building here was used for storing iron and nail rod for the blacksmith shop and nailery. It also served over time for tinsmithing and nail manufacture and as a dwelling. A slave named Issac Jefferson, trained as a tinsmith in Philadelphia, briefly operated the tin shop.” The second spread is titled “The Plantation” and deals specifically with the institution of slavery. It states, “Most of Jefferson’s slaves came to him by inheritance – 20 from his father and 135 from his father-in-law. In 1782, he was the largest slaveholder in Albemarle County. For most of his life he was the owner of 200 slaves, two-thirds of them at Monticello and one-third at Poplar Forest, his plantation in Bedford County.” A photograph of Jefferson’s record of slaves compliments the copy and a sidebar deals directly with the subjects of enslaved families and Sally Hemings. Both of these are new additions and bear quoting here:

The second spread is titled “The Plantation” and deals specifically with the institution of slavery. It states, “Most of Jefferson’s slaves came to him by inheritance – 20 from his father and 135 from his father-in-law. In 1782, he was the largest slaveholder in Albemarle County. For most of his life he was the owner of 200 slaves, two-thirds of them at Monticello and one-third at Poplar Forest, his plantation in Bedford County.” A photograph of Jefferson’s record of slaves compliments the copy and a sidebar deals directly with the subjects of enslaved families and Sally Hemings. Both of these are new additions and bear quoting here:  I have to admit that this trip to Monticello yielded a variety of different conclusions for me. The Thomas Jefferson that I recognize today was a man who may very well have held a sincere paternalistic fondness for his slaves, but at the same time, he held them in the chains of bondage. Despite the fact that many of his servants received specialized training and developed trades that resulted in the creation of great things, they were simultaneously denied the basic principle of freedom. This is where the contradiction of the man who penned the Declaration of Independence lies. Thomas Jefferson was an extraordinary man whose contributions to this country cannot be denied, but he was also a man who held racist views of the period. This is an undeniable truth.

I have to admit that this trip to Monticello yielded a variety of different conclusions for me. The Thomas Jefferson that I recognize today was a man who may very well have held a sincere paternalistic fondness for his slaves, but at the same time, he held them in the chains of bondage. Despite the fact that many of his servants received specialized training and developed trades that resulted in the creation of great things, they were simultaneously denied the basic principle of freedom. This is where the contradiction of the man who penned the Declaration of Independence lies. Thomas Jefferson was an extraordinary man whose contributions to this country cannot be denied, but he was also a man who held racist views of the period. This is an undeniable truth. UPDATE: One additional area that fits the attention of this study is the African-American graveyard that is located on the grounds of the estate. According to the sign, this cemetery is the final resting place of 40+ blacks who lived in slavery at Monticello from 1770-1827. It adds that although the names of Jefferson's slaves were known, it has not been possible to identify any of those buried here. This is perhaps one of the most telling of all the exhibits as a separate burial plot personified the society of segregation that even in death, existed at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.

UPDATE: One additional area that fits the attention of this study is the African-American graveyard that is located on the grounds of the estate. According to the sign, this cemetery is the final resting place of 40+ blacks who lived in slavery at Monticello from 1770-1827. It adds that although the names of Jefferson's slaves were known, it has not been possible to identify any of those buried here. This is perhaps one of the most telling of all the exhibits as a separate burial plot personified the society of segregation that even in death, existed at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello.