Battlefield Baseball

This photograph is believed to be one of the only ones in existence to have

captured a military baseball game during the Civil War. It features soldiers of

Company G, 48th New York State Volunteers playing a game at Fort Pulaski,

Georgia. (Courtesy of Fort Pulaski Military Park)

As I’m in a fully-focused baseball state-of-mind in preparation for the release of You Stink! Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players I thought that I would share an article on the game of baseball during the Civil War. I originally wrote a much shorter form of this piece for Baseball-Almanac and later penned an expanded feature-length version for Civil War Historian magazine. My early work as a baseball historian was actually what led to me becoming a published author. I am now in the process of developing a talk based on You Stink! as my co-author Eric Wittenberg and I plan to do speaking engagements together (whenever possible) as well as apart. Enjoy...

It is considered America’s National Pastime, but far more than just a mere sporting event, baseball has become a major part of the American consciousness. In their book “The Pictorial History of Baseball,” John S. Bowman and Joel Zoss stated, “As part of the fabric of American culture, baseball is the common social ground between strangers, a world of possibilities and of chance, where ‘it’s never over till it’s over.’” Rooted in the American Spirit, rich in legends, folklore and history, it is ultimately a timeless tradition where every game is a new nine-inning chapter and every participant has the chance to be a hero.

One of the simplest and best explanations of the game’s impact on society was penned in 1866 when Charles A. Peverelly wrote, “The game of baseball has now become beyond question the leading feature of the outdoor sports of the United States ... It is a game which is peculiarly suited to the American temperament and disposition; ... in short, the pastime suits the people, and the people suit the pastime.”

During war, following natural disaster, or in the midst of economic hardship, this “game” has always provided an emotional escape for people from every race, religion and background who can collectively find solace at the ballpark. Therefore, it somehow seems fitting that the origins of modern baseball can be traced back to a divided America, when the country was in the midst of a great Civil War. Despite the political and social grievances that resulted in the separation of the North and South, both sides shared some common interests, such as playing baseball.

Although a primitive form of baseball was somewhat popular in larger communities on both sides of the Mason Dixon line, it did not achieve widespread popularity until after the start of the war. The mass concentration of young men in army camps and prisons eventually converted the sport formerly reserved for “gentlemen” into a recreational pastime that could be enjoyed by people from all backgrounds. For instance, both officers and enlisted men played side by side and soldiers earned their places on the team because of their athletic talents, not their military rank or social standing.

[NOTE: In 1857, a convention of amateur ball clubs was called to discuss rules and other issues. Twenty five teams from the northeast sent delegates. The following year, they formed the National Association of Base Ball Players, the first organized baseball league. The league’s annual convention in 1868 drew delegates from over 100 clubs. As the league grew, so did the expenses of playing. Charging admission to games started to become more common, and teams often had to seek out donations or sponsors to make trips.]

Both Union and Confederate officers endorsed baseball as a much-needed morale builder that also provided both mental and physical conditioning. After long details at camp, it eased the boredom and created team spirit among the men. Some soldiers actually took baseball equipment to war with them. When proper equipment was not available they often improvised with fence posts, barrel staves or tree branches for bats and yarn or rag-wrapped walnuts or lumps of cork for balls.

To this day, casualties from the American Civil War (620,000+) still exceed our country’s losses in all other military conflicts. It is estimated that the Union armies had from 2,500,000 to 2,750,000 men. The Confederate strength, known less accurately because of missing records, was from 750,000 to 1,250,000. From 1861 to 1865, both armies suffered tremendous losses and the subsequent damage to the country’s infrastructure cost millions to rebuild.

One of the most widely credited (and criticized) participants in the destruction was Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who put it best when he said, “War is all Hell.” Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee echoed that sentiment when he stated that, “It is well that war is so terrible -- lest we should grow too fond of it.” Perhaps if either side could have foreseen the tragedy that would befall them, a compromise may have been offered in place of musket fire.

Unfortunately, a magnanimous and peaceful conclusion was not meant to be. For four years, a horrific conflict of epic proportions scarred the country’s land and traumatized her citizens. When it finally ended, nearly 2% of the country’s population was dead and millions of dollars in damage had devastated the country’s infrastructure.

Therefore, despite being a welcome distraction while on campaign, baseball was played on some of the most sacred and hallowed of soil that was baptized in the blood of thousands. In addition to the camps, forts and battlefields, contests were also held within the walls of some of the most despicable prison camps one could imagine. These “detention centers” were often death sentences in themselves, as soldiers died from starvation, exposure, disease and dysentery. Without a doubt, these “ballparks on battlefields” were the worst fields whose history goes far beyond that of the game.

The benefits of playing while at war went far beyond fitness, as often the teamwork displayed on the baseball diamond translated into a teamwork mentality on the battlefield. Many times, soldiers would write of these games in the letters sent home, as they were much more pleasant to recall than the hardship of battle. This was perhaps one of the earliest forms of sports journalism and the precursor to the “box-score beat writers” of the 20th-century.

Private Alpheris B. Parker of the 10th Massachusetts wrote, “The parade ground has been a busy place for a week or so past, ball-playing having become a mania in camp. Officers and men forget, for a time, the differences in rank and indulge in the invigorating sport with a schoolboy’s ardor.”

Another private writing home from Virginia recalled, “It is astonishing how indifferent a person can become to danger. The report of musketry is heard but a very little distance from us...yet over there on the other side of the road most of our company, playing bat ball and perhaps in less than half an hour, they may be called to play a Ball game of a more serious nature.”

Sometimes games would be interrupted by the call of battle. George Putnam, a Union soldier humorously wrote of a game that was “called-early” due to the surprise attack on their camp by Confederate infantry, “Suddenly there was a scattering of fire, which three outfielders caught the brunt; the centerfield was hit and was captured, left and right field managed to get back to our lines. The attack...was repelled without serious difficulty, but we had lost not only our centerfield, but...the only baseball in Alexandria, Texas.”

It has been disputed for decades whether Union General Abner Doubleday was in fact the “father of the modern game.” Many baseball historians still reject the notion that Doubleday designed the first baseball diamond and drew up the modern rules. Nothing in his personal writings corroborates this story, which was originally put forward by an elderly Civil War veteran, Abner Graves, who served under him. Still, the City of Cooperstown, NY dedicated Doubleday Field in 1920 as the “official” birthplace of organized baseball. Later, Cooperstown became the home of the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Doubleday was an 1842 graduate of West Point (graduating with A.P. Stewart, D.H. Hill, Earl Van Dorn and James Longstreet) and served in both the Mexican and Seminole Wars. In 1861, he was stationed at the garrison in Charleston Harbor. It is said that it was Doubleday, an artillery officer, who aimed the first Fort Sumter guns in response to the Confederate bombardment that initiated the war. Later he served in the Shenandoah region as a brigadier of volunteers and was assigned to a brigade of Irwin McDowell’s corps during the campaign of Second Manassas. He also commanded a division of the 1st Corps at Sharpsburg and Fredericksburg as well as Gettysburg, where he assumed the command of the 1st Corps after the fall of General John F. Reynolds, helping to repel “Pickett’s Charge.”

Strangely, Doubleday’s outstanding military service is often forgotten, yet his controversial baseball legacy lives on. A report published in 1908 by the Spalding Commission (appointed to research the origin of baseball) credited Union General Abner Doubleday as being the “father of the modern game.” It stated, “Baseball was invented in 1839 at Cooperstown, NY by Abner Doubleday-afterward General Doubleday, a hero of the battle of Gettysburg-and the foundation of this invention was an American children’s game called “One Old Cat.”

Since then, Alexander J. Cartwright, Jr., a descendent of a British sea captain, has been designated as the game’s principal founder. According to sources at the Fort Ward Museum, “In 1842, at the age of 22, Cartwright was among a group of men from New York City’s financial district who gathered at a vacant lot at 27th Street and 4th Avenue in Manhattan to play ‘baseball.’ In 1845, they organized themselves into the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club, restricting the membership to 40 males and assessed annual dues of five dollars. The following year, Cartwright devised new rules and regulations, instituting foul lines, nine players to a team, nine innings to a game and set up a square infield, known as the ‘diamond’ with 90-foot baselines to a side, bases in each corner. He also drew up guidelines for punctuality, designated the use of an umpire, determined that three strikes constituted an out, and that there would be three outs per side each inning.”

Cartwright left the New York area in 1849 to travel. He was drawn by the Gold Rush and stories of adventures in the West. Along the way, he taught the game to Native Americans and mountain men he encountered, spreading interest in the fledgling sport west of the Mississippi. Cartwright died in Hawaii in July of 1892. However, for decades to come, it was Doubleday who remained in the hearts and minds of enthusiasts everywhere as baseball’s father.

To his credit, the general is said to have always demurred on assertions by others that he was the founder of the national game. Yet the legend persisted decades after his death. Regardless of falsely being credited as the sole “inventor” of the modern version, Doubleday was an evident student and fan of the game. Some historians believe that he helped to organize contests in camp while deployed, possibly prior to the Battle of Chancellorsville. At the time of the engagement in early May, some 142 years ago, Doubleday was in command of the 3rd Division, 1st Corps. According to John Hennessy, chief historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Doubleday was in the area from the summer of 1862 through the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, and the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863.

It has been determined that baseball was played “extensively” by Union soldiers in nearby Stafford County during that time, but there is no known documentation of Doubleday’s hand in games thereabouts. Perhaps a more realistic accolade would credit him with the promotion of the exercise as opposed to the invention of it.

Many of these contests were attended by thousands of spectators and often made front-page news equal to the war reports from the field. Ultimately, the Civil War helped fuel a boom in the popularity of baseball, evidenced by the fact that a ball club called the Washington Nationals was born in 1860--145 years before a Major League Baseball team was given the same name in the nation’s capital city of Washington D.C.

In 1861 at the start of the war, an amateur team made up of members of the 71st New York Regiment defeated the Washington Nationals baseball club by a score of 41 to 13. When the 71st New York later returned to man the defense of Washington in 1862, the teams played a rematch, which the Nationals won, 28 to 13. Unfortunately, the victory came in part because some of the 71st Regiment’s best athletes had been killed at Bull Run only weeks after their first game. One of the largest attendances for a sporting event in the nineteenth century occurred on Christmas in 1862 when the 165th New York Volunteer Regiment (Zouaves) played at Hilton Head, South Carolina with more than 40,000 troops looking on. The Zouaves’ opponent was a team composed of men selected from other Union regiments. Interestingly, A.G. Mills, who would later become the president of the National League, participated in the game.

According to George B. Kirsch’s 2003 book “Baseball in Blue & Gray,” John G.B. Adams of the 19th Massachusetts Regiment recounted that “base ball fever broke out” at a Falmouth encampment in early 1863 with both enlisted men and officers playing. The prize was “sixty dollars a side,” meaning the winning team paid the losers that sum. “It was a grand time, and all agreed it was nicer to play base than minie [bullet] ball.”

Adams reported that around the same time, several Union soldiers watched Confederate soldiers play baseball across the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg. Nicholas E. Young of the 27th New York Regiment, who later became a president of baseball’s National League, played the game at White Oak Church in Stafford County. Union soldier Mason Whiting Tyler wrote home that baseball was “all the rage now in the Army of the Potomac.”

George T. Stevens of the New York Volunteers said that in Falmouth, “there were many excellent players in the different regiments, and it was common for one regiment or brigade to challenge another regiment or brigade. These matches were followed by great crowds of soldiers with intense interest.”

Although early forms of baseball had already become high society’s pastime years before the first shots of the Civil War erupted at Fort Sumter, it was the mass participation of everyday soldiers that helped spread the game’s popularity across the nation. In his 1911 history of baseball titled “America’s National Game,” Albert G. Spalding wrote, “Modern baseball had been born in the brain of an American soldier. It received its baptism in the bloody days of our Nation’s direst danger. It had its early evolution when soldiers, North and South, were striving to forget their foes by cultivating, through this grand game, fraternal friendship with comrades in arms.”

He added, “No human mind may measure the blessings conferred by the game of Base Ball on the soldiers of our Civil War. It calmed the restless spirits of men who, after four years of bitter strife, found themselves at once in a monotonous era, with nothing at all to do.”

During the War Between the States, countless baseball games, originally known as “Town Ball,” were organized in army camps and prisons on both sides of the Mason Dixon Line. Very little documentation exists regarding these games and most information has been derived from letters written by officers and enlisted men to their families on the home front. For the hundreds of pictures taken during the Civil War by photography pioneer Mathew Brady’s studio, there is only one photo in the National Archives that clearly captured a baseball game underway in the background. The image was taken at Fort Pulaski, Georgia and shows the “original” New York Yankees of the 48th Volunteers, playing a game in the fortification’s yard.

Several newspaper artists also depicted primitive ballgames and other forms of recreation devised to help boost troop morale and maintain physical fitness. Regardless of the lack of “media coverage,” military historians have proven that baseball was a common ground in a country divided and helped both Union and Confederate soldiers temporarily escape the horror of war.

“Town Ball” is a direct descendant of the British game of “Rounders.” It was played in the United States as far back as the early 1800’s and is considered a stepping stone toward modern baseball. Often referred to as “The Massachusetts Game” it is still played by the Leatherstocking Base Ball Club every Sunday in Cooperstown, New York. According to the game’s official rules as published by The Massachusetts Association of Base Ball Players, May 13, 1858: “Basetenders (infielders) and scouts (outfielders) recorded outs by plugging or soaking runners — a term used to describe hitting the runner (tagging them did not count) with the ball.”

Some additional “Town Ball” rules that are familiar to today’s standard “Baseball” game include: “The Ball being struck at three times and missed, and caught each time by a player on the opposite side, the Striker shall be considered out. Or, if the Ball be ticked or knocked, and caught on the opposite side, the Striker shall be considered out. But if the ball is not caught after being struck at three times, it shall be considered a knock, and the Striker obliged to run. Should the Striker stand at the Bat without striking at good balls thrown repeatedly at him, for the apparent purpose of delaying the game, or of giving advantage to players, the referees, after warning him, shall call one strike, and if he persists in such action, two and three strikes; when three strikes are called, he shall be subject to the same rules as if he struck at three fair balls.”

Army encampments were not the only locations to host “Town Ball” games. Prisons also held them as POW’s struggled to escape the hopelessness of their situation and combat the mind-numbing boredom that confronted them each day. One such institution was Salisbury Prison, which was the only Confederate jail located in North Carolina. The compound was established on 16 acres purchased by the Confederate government on November 2, 1861. The prison consisted of an old cotton factory building measuring 90 x 50 feet, six brick tenements, a large house, a smith shop and a few other small buildings.

Day-to-day life was tough, but prisoners had a large yard with plenty of room to move about. One of the favorite activities before the prison became overcrowded was baseball. So prevalent was the game at Salisbury that it was captured in an 1863 print. This illustration represents one of the earliest depictions of the game and recalls the days before overcrowding greatly diminished the camp’s living conditions. The illustration was penned by Otto Boetticher, a commercial artist from New York City, who had enlisted in the 68th New York Volunteers in 1861 at the age of 45. He was captured in 1862 and was sent to the prison camp at Salisbury. During his time there he produced a drawing that depicted the game in a more pastoral than prison-like setting.

A field reporter named W.C. Bates mentioned the presence of baseball at Salisbury in his “Stars and Stripes” publication. He added ”that we have no official report of the match-game of baseball played in Salisbury between the New Orleans and Tuscaloosa boys, resulting in the triumph of the latter; the cells of the Parish Prison were unfavorable to the development of the skill of the ‘New Orleans nine.’ Prisoner Gray mentions that baseball was played nearly every day the weather permitted. Claims have been made that these were the first baseball games played in the South.”

“Prisoner Gray” was actually Dr. Charles Carroll Gray, who indicated in his diary on July 4th that the day was “celebrated with music, reading of the Declaration of Independence, sack and foot races in the afternoon, and also a baseball game.” Gray fondly recalled that baseball was played almost every day. Sgt. William J. Crossley of Company C, 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, described in his memoirs at Salisbury prison that “the great game of baseball generated as much enjoyment to the Rebs as the Yanks, for they came in hundreds to see the sport.”

More than a decade after the Civil War ended, the National League was developed. Coincidentally, it was the same year that General George Armstrong Custer was killed, along with two hundred and sixty-four Union Calvary troopers, after engaging Indian warriors at Little Bighorn. The year was 1876, and the National League of Professional Baseball was formed with an eight-team circuit consisting of the Boston Red Stockings, Chicago White Stockings, Cincinnati Red Legs, Hartford Dark Blues, Louisville Grays, Philadelphia Athletics, Brooklyn Mutuals and St. Louis Browns. It has been reported that many members of the U.S. Calvary, most of them veterans of the Civil War, engaged in baseball games to pass the time while protecting the western territories. Some of them returned home to witness the likes of Ross Barnes of Chicago hit the first National League home run which was an inside the park variation. A Cincinnati pitcher named William “Cherokee” Fisher served up that historic pitch.

Regardless of its location, whether in prison camps or in the field, baseball provided an escape from the harsh realities of war and ultimately improved the morale of troops who were obviously homesick, scared, and in some cases, traumatized by the horrors they had witnessed on the battlefield. After the war ended, many men from both sides returned home to share the game that they had learned near the battlefield. Eventually organized baseball grew in popularity abroad and helped bring together a country that had been torn apart for so many years.

Today, over a century later, baseball is still a popular American institution and remains a testament to both “Billy Yank” AND “Johnny Reb” who laid down their muskets to pick up a ball and help to establish a National Pastime. Perhaps it was Walt Whitman, one of America’s most prolific poets, who correctly predicted how a game played with a stick would grow into one of our country’s most prized possessions. He wrote, “I see great things in baseball. It’s our game - the American game. It will take our people out-of-doors, fill them with oxygen, and give them a larger physical stoicism. Tend to relieve us from being a nervous, dyspeptic set. Repair these losses and be a blessing to us.”

Baseball during the Civil War was indeed a blessing, but the fields that hosted it were anything but. Even today it is far too easy for us to look back and forget the carnage that took place across the American landscape during the “Great Divide.” Each year, millions of tourists travel to our National Battlefield Parks to honor the memories of their fallen ancestors. When they arrive, everything is perfect. The grass is neatly trimmed and the markers are polished. The freshly painted cannons are all lined up neatly and the flags dance in the gentle breeze that greets each visitor. There is a sense of romance and pageantry that is virtually impossible to escape.

In truth, they are standing in the shadow of death. And it is this shadow that hangs over every field that witnessed America’s War Between the States. Some were battlefields, and some were ball fields. Unfortunately most were killing fields too.

Sources:

Adams, J.G. B. Reminiscences of the 19th Massachusetts Regiment. Boston: Wright and Porter, 1899.

Aubrecht, Michael A., “Baseball and the Blue and Gray,” Baseball-Almanac. Pinstripe Press: 2004.

Fort Ward Museum. “Civil War Baseball: Battling on the Diamond.” Fort Ward Museum and Historical Site webpage.

Frommer, Harvey. “Primitive Baseball: The First Quarter Century of the National Pastime.”

Kirsch, George B., “Bats, Balls and Bullets: Baseball and the Civil War,” Civil War Times Illustrated. Vol. XXXVI, No. 2 (May, 1998).

Kirsch, George B. Baseball in Blue & Gray: The National Pastime During the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Millen, Patricia, “ From Pastime to Passion: Baseball and the Civil War,” Heritage Books (January 2001).

The truth behind Lee's decision

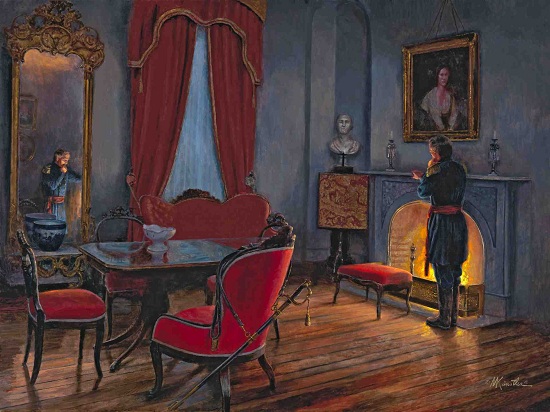

The Great Decision, by Mort Kunstler 2012

When I first started researching information for Mort Kunstler’s latest print (depicting Robert E. Lee at Arlington, struggling over the decision to/or not-to assume command of the Federal Army), I was quite surprised by how much misconception there is surrounding the event. It appears that many folks, at least across the Internet, believe that this was for lack of a better term, a “no-brainer.” If one goes by the depiction of this event in the film Gods and Generals (watch here), it would seem that Lee took little more than a few seconds to come to his conclusion. Some of the southern heritage folks have also depicted Lee as vehemently denouncing the offer to take up arms against his state and immediately declaring his loyalty to Virginia. This is not true.

The truth is that Robert E. Lee struggled greatly with what would not only be the biggest, but also perhaps the most difficult decision of his life. One has to remember that he was one of the most respected military officers in the country at the time, likened only to George Washington in popularity among his peers, and that his entire family legacy was based on serving the United States. Lee’s military career spanned over three decades of exemplary service. To assume that he would cast aside his sense of duty to the Union so callously is not only an oversimplification of the decision, but also of the man. Here is how Mort and I have chosen to depict the real event:

The Great Decision, Lee at Arlington House, April 19, 1861

By Michael Aubrecht (written for American Spirit Publishing)

ORDER PAINTING HERE

Remembered today as the leader of the Confederate States Army, Robert E. Lee’s military service was one of distinction long before the Civil War. With a family tree firmly rooted in the armed forces of early Colonial America, his service to the United States Army spanned 32 years. During this time he gained a reputation as a gifted engineer and an exceptional officer. After fighting in the Mexican-American War, he served as the superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

In October of 1859, President James Buchanan personally requested Lee to assume the command of a contingent of United States Marines and suppress a group of 21 abolitionists who had seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, VA in an attempt to incite a slave rebellion. Later known as “John Brown’s Raid,” this seminal event is often referred to as the actual start the American Civil War. Robert E. Lee was therefore a leading commander, albeit on different sides, at the very beginning of the conflict and at the very end of it.

When newly-elected President Abraham Lincoln gave control of the Union Army to Winfield Scott, the general immediately requested that Robert E. Lee be given a top command position. On April 18, 1861, then Colonel Lee was summoned to Washington D.C. where he met with Francis P. Blair who said, “I come to you on the part of President Lincoln to ask whether any inducement that he can offer will prevail on you to take command of the Union army.”

Taking command of Union forces in Washington would require Lee to take up arms against his own state of Virginia. Accepting the conundrum of his situation, Lee returned to his beloved home at Arlington House where he spent the next two days pondering the repercussions of his decision. After hours of contemplative thought, he graciously rejected the offer and ended his illustrious career in the United States Army.

Lee’s resignation letter to General Scott clearly depicted the difficulty of his decision. It read: “I have felt that I ought not longer to retain any commission in the Army. I therefore tender my resignation which I request you will recommend for acceptance. It would have been presented at once but for the struggle it has cost me to separate myself from a service to which I have devoted all the best years of my life, and all the ability I possessed.” He closed with “Save in the defense of my native state shall I ever again draw my sword.”

Mort Kunstler’s comments:

In 1995, while I was working on the book Jackson & Lee – Legends in Grey, I did a small painting which I called “The Great Decision.” As the subject of the piece was so compelling, I knew that I would eventually use it as the study for a major oil painting. Now all these years later, I have finally done it!

Robert E. Lee was a colonel in the United States Army when the Civil War started. On April 18, 1861 he was summoned across the Potomac to the nation’s capital and offered command of the Federal Army. Although he harbored mixed emotions over the issues of secession and slavery, he could not take up his sword against his home state of Virginia. After departing Washington, D.C. and returning to his home at Arlington House (located at the present day location of Arlington National Cemetery), he spent April 19th pondering his great decision. The following day he tendered his resignation from the U.S. Army, traveled south to Richmond and accepted command of Virginia’s troops with the rank of major general.

There are always problems to solve with every painting, but with “The Great Decision” they were very different. The challenge for an artist to depict Lee’s decision was quite rudimentary. However, Robert E. Lee, on April 19, 1861 simply did not look like the Robert E. Lee that we tend to remember. He was much younger, dark-haired and did not have a beard. This required me to reacquaint myself with a man whom I had painted dozens of times before.

I made arrangements to visit Arlington House and meet with its curator Maria Capozzi. Unfortunately, my arrival took place just a few weeks after an earthquake had rumbled across the Piedmont Region of Virginia on August 23, 2011. As a result there was structural damage to the building and all of the beautiful fully-restored rooms had been emptied of all furnishings. Despite this, Ms. Capozzi was still able to provide me with the information that I needed.

I finally settled on what is called the “White Parlor” for the location of the painting although Lee may have thought about his epic decision just about anywhere on the grounds. I still faced the problem of portraying him without his trademark white hair and beard. I realized that if I presented the scene in the evening it would be difficult to tell whether Lee’s hair was light or dark. I also felt that if I could compel the eye of the viewer to focus on the back view of the man, they would naturally pan to the left and see his reflection in the mirror. This was accomplished by the use of the lighting effect from the fire. I also posed Lee with his hand upon his chin. This served two purposes. First, the gesture is one of deep thought. Second, the hand would serve to cover the fact that he had no beard at that time.

I had chosen the White Parlor for my scene specifically for its proportions and elegant furnishings. The mantle above the fireplace was personally designed by the general and the furnishings were chosen by both Lee and his wife, Mary Custis Lee. The bust I included is of George Washington, Mary Custis Lee’s ancestor.

As my firsthand observations for this painting were made wearing a hard hat, while Lee’s magnificent manor was undergoing restoration, I can only hope that by the time this print is released, Arlington House will be fully restored and open to the public once again. It is a home that has witnessed so many historical moments, including the one where one of America’s greatest soldiers made one of his most difficult decisions.

Last talk transcript...

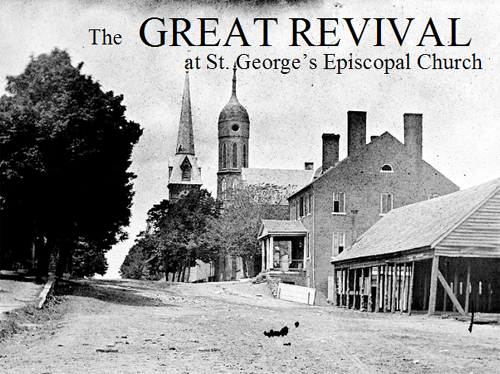

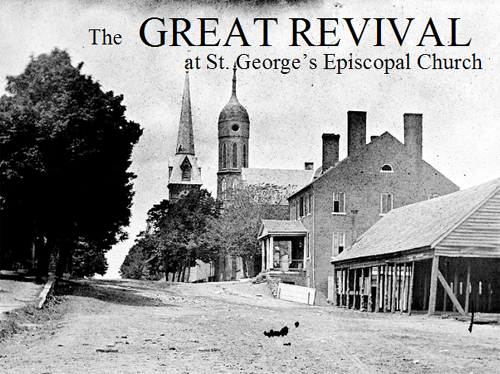

There is an audio recording of this speech yet to come. In the meantime, here is the transcript titled: The Great Revival at St. George’s Episcopal Church. This presentation was given on March 18, 2012 at St. George’s as part of their Civil War Forum Series. It was an incredible piviledge for me to be on this bill as the series also featured Robert Krick, Donald Pfanz, and John Hennessy. Good morning ladies and gentlemen. I would like to thank Ed Jones and John Hennessy for setting up this invitation to speak today. When I was conducting research for my book on Fredericksburg’s historical churches, St. George’s was one of my favorites. I don’t just say that in passing. As you can see here, every press and promotional photo that was taken of me following the book’s release, including the story that Ed’s folks did in The Free Lance-Star, was taken here at this church. And the posters for my first speaking engagements also used St. George’s clock tower as the imagery. So for me to have the opportunity to come back here and speak about the Great Revival today is really a thrill.

Let's begin by briefly looking at the subject of faith and its impact during the Civil War and then we’ll specifically examine St. George’s experiences. Please note that I made a conscious effort in this talk to include letters that I will read from as I want you to experience the story of the Great Revival through the words of those who actually lived it – and not just mine. I also want to leave some time for any questions or discussion that you may have.

Religion in America during the 19th-Century played a vital role politically, socially, and of course spiritually. Therefore it is no surprise that faith remained a welcome companion to soldiers out in the field and citizens back on the home front. Many troops became 'born-again' during the American Civil War as the romance and pageantry that once attracted volunteers by the thousands wore away as the killing fields spread across the country. From firesides of the Eastern Campaign here in Virginia to the army campsites of Tennessee, both soldiers and citizens came to Christ by the thousands.

Reverend John C. Granberry who was a Chaplain of the 11th Virginia Regiment observed this phenomenon firsthand and wrote to the Richmond Christian Advocate:

I have never before witnessed such a wide-spread and powerful religious interest among the soldiers…It would delight your heart to mark the seriousness, order, and deep feeling, which characterizes all our meetings.

Chaplain William B. Owen of the 17th Mississippi Infantry Regiment echoed that sentiment after he preached several evenings of revival sermons. He recalled that:

It was a touching scene to see the stern veterans of many a hard-fought field, who would not hesitate to enter the deadly breach or charge the heaviest battery, trembling under the power of divine truth.

Throughout the Civil War the church was repeatedly called upon to meet many new challenges that came with a divided nation. Protecting the sanctity of religious practices remained a top priority for those who were extremely concerned about the repercussions of the wartime climate. First and foremost was the inevitable splitting of the denominations following the South's secession. And although there appeared to be no immediate hostilities harbored by Christian leaders on either side, the fact remained that the political split in the country - also split the church. This had a profound effect on virtually every aspect of their operations.

For example, up until the outbreak of the Civil War, the American Bible Society, based in New York, handled the production and distribution of most religious materials including Bibles and tracts. After the conflict began, an entirely new system had to be formed in order to meet the needs of the Southern congregations. Many of these dilemmas were addressed in the minutes of the Presbyterian Church's General Assembly who addressed the need to establish a new chapter of the Bible Society to shoulder the task of producing and distributing religious materials in the Confederate States. The result was the Southern Baptist Bible Society who began producing bibles. Privatized organizations representing a multitude of denominations also stepped forward by printing and distributing gospel tracts in the field.

(On a quick side-note, if you ever want to dig deeper into this subject, let me recommend a visit to the National Civil War Chaplains Museum down at Liberty University. They have an amazing collection of bibles and other religious artifacts that once belonged to soldiers and chaplains.)

Maintaining the Sabbath and deploying chaplains and priests into army camps to conduct worship services while on campaign remained a critical need. Whenever possible, a schedule of morning and evening worship on Sundays, as well as Wednesday prayer meetings, was implemented. Often, preachers from nearby congregations would travel out to the camps to minister to the troops. Some of the more noteworthy men to come out of this service were the Reverend Beverly Tucker Lacy who preached to thousands as a member of Stonewall Jackson’s staff and Father William Corby of the famed Irish Brigade who later became the president of Notre Dame.

Despite their postwar accolades these men were not always met with enthusiasm. According to some accounts, religion did not accompany many soldiers at the start of the war. The magazine Christianity Today recalled the trials and tribulations with living a Godly life while on campaign. It stated:

Day-to-day army life was so boring that men were often tempted to 'make some foolishness,' as one soldier typified it. Christians complained that no Sabbath was observed. General Robert McAllister, an officer who was working closely with the United States Christian Commission, complained that a 'tide of irreligion' had rolled over his army 'like a mighty wave.'

Confederate General Braxton Bragg echoed this frustration and complained that, “We have lost more valuable lives at the hands of whiskey sellers than by the [minie]balls of our enemies.”

One Confederate officer who was perhaps the most pious of his peers was General Thomas Jackson. After realizing a lack of participation in the early war effort by the church, Jackson sent a letter to the Southern Presbyterian General Assembly, petitioning them for support. In it he stated:

Each branch of the Christian Church should send into the army some of its most prominent ministers who are distinguished for their piety, talents and zeal; and such ministers should labor to produce concert of action among chaplains and Christians in the army. These ministers should give special attention to preaching to regiments which are without chaplains, and induce them to take steps to get chaplains, to let the regiments name the denominations from which they desire chaplains selected, and then to see that suitable chaplains are secured.

He added:

A bad selection of a chaplain may prove a curse instead of a blessing. ...Denominational distinctions should be kept out of view, and not touched upon. And, as a general rule, I do not think a chaplain who would preach denominational sermons should be in the army. His congregation is his regiment, and it is composed of various denominations. I would like to see no question asked in the army of what denomination a chaplain belongs to; but let the question be, Does he preach the Gospel?

As the war progressed, a movement referred to as "The Great Revival" took place across the South. Beginning in the fall of 1863, this event was in full progress throughout the Army of Northern Virginia where thousands of rebel soldiers in Robert E. Lee's force were converted before the revival was interrupted by General U.S. Grant's attack in May of 1864.

The beginning of this revival appears to have started in the winter of 1862-1863 in Fredericksburg and the rest of the Lower Valley, and Chancellorsville, though its roots were earlier in the war. Some have narrowed it down to the first service performed at the Williams Street Methodist Church in Fredericksburg by the chaplain of the 17th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, of Barksdale’s Brigade, Rev. William B. Owen. He was soon joined by privates Clairborne McDonald and Thomas West of the 13th Mississippi, and they appeared to be filling the fairly large church seven nights a week. It was written in a letter by private William H. Hill of Company H, 13th Mississippi, that:

From 40 to 50 soldiers are at the mourner’s bench every night waiting to be saved from their sins.

During the revival, preachers told of how soldiers would form “reading clubs,” in which they would pass around a well-worn Bible, sharing the Gospel. Always hungry for scarce Testaments and religious tracts, the soldiers would see chaplains approaching camp and cry out “Yonder comes the Bible and Tract man!” and run up to him and beg for Bibles and Testaments “as if they were gold guineas for free distribution.” One minister recalled “I have never seen more diligent Bible-readers than we had in the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Dr. Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr., author of A Shield and Hiding Place: The Religious Life of the Civil War Armies, reported that:

The best estimates of conversions in the Union forces place the figure between 100,000 and 200,000 men-about 5-10 percent of all individuals engaged in the conflict. In the smaller Confederate armies, at least 100,000 were converted. Since these numbers include only 'conversions' and do not represent the number of soldiers actually swept up in the revivals-a yet more substantial figure-the impact of revivals during the Civil War surely was tremendous.

At a local level the numbers were a bit more modest. In The Great Revival of 1863 historian Troy Harman writes:

The revivals from the autumn of 1862 through the spring of 1863 also included large gatherings in the churches of Fredericksburg, which were mostly abandoned by the citizens of that town during the battle. When services were first held in these shell-marked churches in January 1863, the numbers were moderate enough to meet in smaller buildings such as the Presbyterian Church. As the soldier congregations grew, they moved to larger structures such as those of the Methodist church, and finally the largest Episcopal sanctuary. Reverend Bennett recalled a service in the latter facility on March 27, 1863 noting, “At 11:00 [A. M.] we assembled at the Episcopal Church. On this occasion, perhaps 1,500 were in attendance, mostly soldiers. Every grade, from private to Major General was represented.”

The Reverend William Jones D.D (who wrote an excellent account of his time during the war titled Christ in the Camp) recalled his experiences of evangelizing to the troops in his memoirs when he wrote:

Long before the appointed hour the spacious Episcopal church, kindly tended by its rector, is filled - nay, packed-to its utmost capacity-lower floor, galleries, aisles, chancel, pulpit steps and vestibule-while hundreds turn disappointed away, unable to find even standing room… I remember that I preached to this vast congregation the very night before Hooker crossed the river, bringing the battles of Second Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville - that, in my closing appeal, I urged them to accept Christ then and there, because they did not know but that they were hearing their "last invitation," and that sure enough we were aroused before the day the next morning by the crossing of the enemy.

The army was not the only ones suffering. In a personal letter written from Dr. Harry Lovell, who served with the Confederate Army, local citizens and soldiers alike benefited by the presence of this much-needed revival. To his sweetheart the doctor sent:

For the last week or two there has been a good revival going on at the Episcopal Church. Several in which there were a great many soldiers received into the church and baptized. The city presents a baleful appearance. There is no estimating the suffering caused by the shelling of the place. There are hundreds of men who were yard lively who are now reduced to beggary. The poor women and children are starving in every quarter. It is or ought to be a shame in any nation to create such suffering…

Not surprising this local movement spread from the confines of the churches out into the army camps where soldiers would in turn come to town to participate in worship services. Simeon David, a member of the 14th North Carolina Infantry wrote in a letter home that:

There is a very general revival of religion going on in our Brigade at this time, baptizing every day. There are several churches in the surrounding country that our men go to every Sabbath.

Jo Shaner of the Rockbridge Artillery experienced the revival and enthusiastically wrote to his parents about his own spiritual transformation. He said:

I am happy to say that the Lord has been doing great work for us - there has been some 20 or more that has come forward and made a public profession that they intended to follow Christ and I suppose that you both will be glad to hear that I have not been left out of that number. Yes by the help of the Lord I intend to lead a new life - I feel as though I was a new man some 10 or 12 of that number joined the church - Capt Graham also expressed a desire to become a member of the church.

Now what I find to be extraordinary when reflecting on the Great Revival at St. George’s is the fact that amidst all of the occupation and destruction that descended on the city of Fredericksburg, they were one of the few churches to not only remain open - but also pro-active. Like the rest of its community, the bombardment of the town by Federal artillery in December of 1862 had a profound effect on the church and its congregation.

As one of the tallest and most distinctive structures in all of Fredericksburg, St. George’s was particularly threatened by Union cannoneers that were positioned at Stafford Heights, on the bluff just behind the stately Chatham Manor. The towering green steeple had become a target for the gunners and the structure would eventually be hit over twenty-five times during the course of that initial battle. A Union artillerist had recalled a comrade’s attempt to destroy the church’s clock: “An officer of another battery remarked that the first shot he put into the city should pass through the clock; in fact, he proposed to breach the wall in such a way that the clock would fall into the body of the church. He explained that he felt impelled to this act through a sense of predestined responsibility.” (He must have been a Presbyterian like me.)

Of course once they were in occupation of the city, St. George's took on a new role from a Federal target to Federal hospital. One of my very favorite quotes, not only from my book, but also from all quotes I've read in all of my studies of the Civil War, came from another Yankee soldier stationed up in the tower here at St. Georges. He recalled:

Orders came to withdraw the pickets from Fredericksburg. I was in the church steeple, and had been forgotten. When I came down at night, and went to my old position in the rifle pits, I found that my whole company was gone. I was holding the entire town by myself.

As the Federal Army retreated from Fredericksburg and both sides went into winter quarters, local clergy did their part in ministering to the remaining soldiers and citizens. By January and February a religious fervor was spreading. The Religious Herald reported on February 26, 1863 that revival meetings were occurring, “fifty-five consecutive days and nights without regard to weather or other untoward circumstances.” It went on to say that, “Each day, sermons and prayer meetings were virtually hourly affairs from noon until late at night as soldiers became alive with religious animation.”

A typical week of worship included Sunday School, preaching, prayer meetings, Bible classes, inquiry, exhortations, and singing meetings. The evening assemblies, which gained so much attention, were impressive sights indeed. Reverend Bennett recalled, “You behold a mass of men seated on the earth all around you…in the wild woods, under a full moon, aided by the light of side strands.” John H. Worsham, a soldier in the 21st Virginia Infantry, painted a picture of the typical outdoor revival forum, writing:

Trees were cut from the adjoining woods, rolled to this spot, and arranged for seating of at least 2,000 people. At the lower end a platform was raised with logs, rough boards were placed on them, and a bench was made at the far side for the seating of preachers. In front was a pulpit, or desk, made from a box. Around this platform and around the seats, stakes were driven into the ground about ten or fifteen feet apart. On top of them were placed baskets of iron wire, iron hoops, etc. Into these baskets were placed chunks of lightwood, and at night they were lighted and threw a red glare far beyond the confines of the place of worship.

Later in the following spring, Federal forces once again entered the city, much to the dismay of its shell-shocked citizens. The Reverend Alfred Magill Randolph, rector of St. George’s, wrote to his wife from Richmond describing the renewed plight of Fredericksburg’s townsfolk:

My Darling Sallie,

Owing to the condition of the RR and the dread of Yankee Cavalry who are thought to be between here and Ashland trains have not yet been allowed to go to Fredbg—One is expected to go this morning—if so I will go—I am very anxious about our boys—I see that several of Gen Jackson’s staff fell killed or wounded at the time he was wounded—names are not given—we learn, too, that Early’s division had the hardest fighting to do in front of Fredbg and I cannot leave here until I hear from them—it would be duty to them or to Ma—From what I gather the rectory is complete and the Yankee Army beaten and broken, but with terrible loss on our side—Our old town has again been occupied for two days by the enemy and I suppose suffered as before—I have heard as yet nothing from individual friends in the army—

Less than one year later, in April of 1864, Reverend Randolph recalled preaching a ‘revivalesque’ sermon to a large congregation in the upper part of the crippled church. Despite all of the damage and destruction in the downtown area, citizens still managed to traipse through the rubble in order to take communion at periodic Sunday services that were conducted by the reverend and no one else. Attendance at these impromptu services fluctuated from two to three hundred people, and soldiers were often present. Reverend Randolph noted that the possibility of his entire congregation returning to the town in the near future was highly improbable, as provisions were so scarce and the threat of reoccupation remained constantly on the minds of those staying behind.

Of course St. George’s, like Fredericksburg, not only survived the war, but continued to prosper. Your congregation is a testament to that resolve. Here are the meeting minutes regarding the resignation of Rev. Randolph and a collection to aid in remedying the damages caused by quote “shot and shell in the bombardment of December 1862.” In some ways this church was directly responsible for hosting the spiritual conversion of thousands of soldiers who most likely returned home and continued to spread the gospel in their own denominations.

According to historian Troy Harmon:

For the numerous Confederates who participated in revival, their lives changed as they became more sincere about service to country and about personal integrity. Because the issue of where each converted soldier would spend his eternity was settled, each of them perhaps was more apt to risk the dangers of the battlefield. Additionally, it is reasonable to believe that an ample number of them returned home in 1865 to become devout churchgoers and spiritual leaders. Whatever their legacy, these survivors must have reflected back on the two immense revivals in the Army of Northern Virginia, with both amazement and fondness. Most likely, when they pondered the hardships of the war, they shared thoughts of Reverend Wallace when he wrote, “and among the sad memories…the recollection of the great and blessed work of grace that swept through all military grades, from the General to the drummer boy is ‘the silver lining’ to the dark and heavy cloud of war that shook its terrors on our land.”

St. George’s Episcopal Church is therefore not only the site of a great revival, but also a shining example of light amidst one of the darkest periods in American history. The Rev. DD Jones summarized the positive repercussions of this movement when he wrote:

In the midst of the titanic struggle of the American War Between the States, a spiritual war for the souls of men was waged with equal vigor. From 1861 to 1865, many thousands of soldiers professed Christ as their Savior and Lord, and many more were renewed in their commitment to serve God in camp and battlefield.

So what was the historical effect of the Great Revival here at St. George’s? How do we measure its impact? One can look at the results of a battle and immediately see how it shaped the course of the war, yet a religious experience like the one I have discussed today must be measured differently. What is its legacy? Well, its legacy can be traced through the military and civilian believers that I’ve quoted today…converts who recalled this event that occurred almost 150 years ago as being a major transformation in their lives. No doubt those that survived the war continued to practice their newfound faith.

In closing today, I want to share a thought-provoking prayer that is believed to have been found on the body of a dead Confederate soldier. This declaration (to me) personifies the transformation that I mentioned and is a lasting testament to the steadfast belief that may have come about as the result of the Great Revival.

I asked God for strength, that I might achieve,

I was made weak, that I might learn humbly to obey.

I asked God for health, that I might do greater things,

I was given infirmity, that I might do better things.

I asked for riches, that I might be happy,

I was given poverty, that I might be wise.

I asked for power, that I might have the praise of men,

I was given weakness, that I might feel the need of God.

I asked for all things, that I might enjoy life,

I was given life, that I might enjoy all things.

I got nothing that I asked for - but everything I had hoped for.

Almost despite myself, my unspoken prayers were answered.

I am among men, most richly blessed.

[Thank you.]

Last week’s film shoot in Atlanta was a total success. The documentaries that we are producing at the U.S. Marshals Service will showcase the extraordinary work done by the fugitive task forces and we now have hours of great footage to choose from. Unfortunately it seems that my spring schedule refuses to allow me to slow down. I just accepted an invitation to judge the ‘History Books’ category of the National Federation of Press Women’s Annual Communication Contest. I also have another speaking engagement at the Richmond Civil War Roundtable to prepare for and several new posts including the audio of last week’s talk at the Civil War Forum and the new baseball book release. Stay tuned for sporadic posts on all these commitments as time permits. (Photo by Shane McCoy, U.S. Marshals Service)

Last week’s film shoot in Atlanta was a total success. The documentaries that we are producing at the U.S. Marshals Service will showcase the extraordinary work done by the fugitive task forces and we now have hours of great footage to choose from. Unfortunately it seems that my spring schedule refuses to allow me to slow down. I just accepted an invitation to judge the ‘History Books’ category of the National Federation of Press Women’s Annual Communication Contest. I also have another speaking engagement at the Richmond Civil War Roundtable to prepare for and several new posts including the audio of last week’s talk at the Civil War Forum and the new baseball book release. Stay tuned for sporadic posts on all these commitments as time permits. (Photo by Shane McCoy, U.S. Marshals Service)