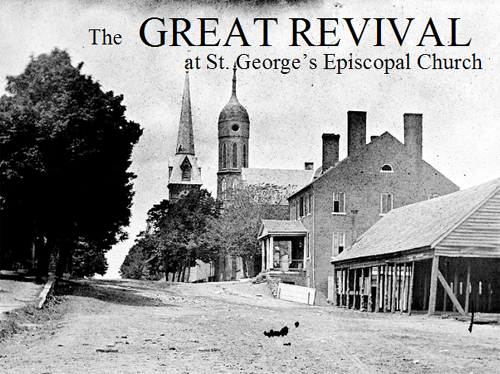

Good morning ladies and gentlemen. I would like to thank Ed Jones and John Hennessy for setting up this invitation to speak today. When I was conducting research for my book on Fredericksburg’s historical churches, St. George’s was one of my favorites. I don’t just say that in passing. As you can see here, every press and promotional photo that was taken of me following the book’s release, including the story that Ed’s folks did in The Free Lance-Star, was taken here at this church. And the posters for my first speaking engagements also used St. George’s clock tower as the imagery. So for me to have the opportunity to come back here and speak about the Great Revival today is really a thrill.

Let's begin by briefly looking at the subject of faith and its impact during the Civil War and then we’ll specifically examine St. George’s experiences. Please note that I made a conscious effort in this talk to include letters that I will read from as I want you to experience the story of the Great Revival through the words of those who actually lived it – and not just mine. I also want to leave some time for any questions or discussion that you may have.

Religion in America during the 19th-Century played a vital role politically, socially, and of course spiritually. Therefore it is no surprise that faith remained a welcome companion to soldiers out in the field and citizens back on the home front. Many troops became 'born-again' during the American Civil War as the romance and pageantry that once attracted volunteers by the thousands wore away as the killing fields spread across the country. From firesides of the Eastern Campaign here in Virginia to the army campsites of Tennessee, both soldiers and citizens came to Christ by the thousands.

Reverend John C. Granberry who was a Chaplain of the 11th Virginia Regiment observed this phenomenon firsthand and wrote to the Richmond Christian Advocate:

I have never before witnessed such a wide-spread and powerful religious interest among the soldiers…It would delight your heart to mark the seriousness, order, and deep feeling, which characterizes all our meetings.

Chaplain William B. Owen of the 17th Mississippi Infantry Regiment echoed that sentiment after he preached several evenings of revival sermons. He recalled that:

It was a touching scene to see the stern veterans of many a hard-fought field, who would not hesitate to enter the deadly breach or charge the heaviest battery, trembling under the power of divine truth.

Throughout the Civil War the church was repeatedly called upon to meet many new challenges that came with a divided nation. Protecting the sanctity of religious practices remained a top priority for those who were extremely concerned about the repercussions of the wartime climate. First and foremost was the inevitable splitting of the denominations following the South's secession. And although there appeared to be no immediate hostilities harbored by Christian leaders on either side, the fact remained that the political split in the country - also split the church. This had a profound effect on virtually every aspect of their operations.

For example, up until the outbreak of the Civil War, the American Bible Society, based in New York, handled the production and distribution of most religious materials including Bibles and tracts. After the conflict began, an entirely new system had to be formed in order to meet the needs of the Southern congregations. Many of these dilemmas were addressed in the minutes of the Presbyterian Church's General Assembly who addressed the need to establish a new chapter of the Bible Society to shoulder the task of producing and distributing religious materials in the Confederate States. The result was the Southern Baptist Bible Society who began producing bibles. Privatized organizations representing a multitude of denominations also stepped forward by printing and distributing gospel tracts in the field.

(On a quick side-note, if you ever want to dig deeper into this subject, let me recommend a visit to the National Civil War Chaplains Museum down at Liberty University. They have an amazing collection of bibles and other religious artifacts that once belonged to soldiers and chaplains.)

Maintaining the Sabbath and deploying chaplains and priests into army camps to conduct worship services while on campaign remained a critical need. Whenever possible, a schedule of morning and evening worship on Sundays, as well as Wednesday prayer meetings, was implemented. Often, preachers from nearby congregations would travel out to the camps to minister to the troops. Some of the more noteworthy men to come out of this service were the Reverend Beverly Tucker Lacy who preached to thousands as a member of Stonewall Jackson’s staff and Father William Corby of the famed Irish Brigade who later became the president of Notre Dame.

Despite their postwar accolades these men were not always met with enthusiasm. According to some accounts, religion did not accompany many soldiers at the start of the war. The magazine Christianity Today recalled the trials and tribulations with living a Godly life while on campaign. It stated:

Day-to-day army life was so boring that men were often tempted to 'make some foolishness,' as one soldier typified it. Christians complained that no Sabbath was observed. General Robert McAllister, an officer who was working closely with the United States Christian Commission, complained that a 'tide of irreligion' had rolled over his army 'like a mighty wave.'

Confederate General Braxton Bragg echoed this frustration and complained that, “We have lost more valuable lives at the hands of whiskey sellers than by the [minie]balls of our enemies.”

One Confederate officer who was perhaps the most pious of his peers was General Thomas Jackson. After realizing a lack of participation in the early war effort by the church, Jackson sent a letter to the Southern Presbyterian General Assembly, petitioning them for support. In it he stated:

Each branch of the Christian Church should send into the army some of its most prominent ministers who are distinguished for their piety, talents and zeal; and such ministers should labor to produce concert of action among chaplains and Christians in the army. These ministers should give special attention to preaching to regiments which are without chaplains, and induce them to take steps to get chaplains, to let the regiments name the denominations from which they desire chaplains selected, and then to see that suitable chaplains are secured.

He added:

A bad selection of a chaplain may prove a curse instead of a blessing. ...Denominational distinctions should be kept out of view, and not touched upon. And, as a general rule, I do not think a chaplain who would preach denominational sermons should be in the army. His congregation is his regiment, and it is composed of various denominations. I would like to see no question asked in the army of what denomination a chaplain belongs to; but let the question be, Does he preach the Gospel?

As the war progressed, a movement referred to as "The Great Revival" took place across the South. Beginning in the fall of 1863, this event was in full progress throughout the Army of Northern Virginia where thousands of rebel soldiers in Robert E. Lee's force were converted before the revival was interrupted by General U.S. Grant's attack in May of 1864.

The beginning of this revival appears to have started in the winter of 1862-1863 in Fredericksburg and the rest of the Lower Valley, and Chancellorsville, though its roots were earlier in the war. Some have narrowed it down to the first service performed at the Williams Street Methodist Church in Fredericksburg by the chaplain of the 17th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, of Barksdale’s Brigade, Rev. William B. Owen. He was soon joined by privates Clairborne McDonald and Thomas West of the 13th Mississippi, and they appeared to be filling the fairly large church seven nights a week. It was written in a letter by private William H. Hill of Company H, 13th Mississippi, that:

From 40 to 50 soldiers are at the mourner’s bench every night waiting to be saved from their sins.

During the revival, preachers told of how soldiers would form “reading clubs,” in which they would pass around a well-worn Bible, sharing the Gospel. Always hungry for scarce Testaments and religious tracts, the soldiers would see chaplains approaching camp and cry out “Yonder comes the Bible and Tract man!” and run up to him and beg for Bibles and Testaments “as if they were gold guineas for free distribution.” One minister recalled “I have never seen more diligent Bible-readers than we had in the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Dr. Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr., author of A Shield and Hiding Place: The Religious Life of the Civil War Armies, reported that:

The best estimates of conversions in the Union forces place the figure between 100,000 and 200,000 men-about 5-10 percent of all individuals engaged in the conflict. In the smaller Confederate armies, at least 100,000 were converted. Since these numbers include only 'conversions' and do not represent the number of soldiers actually swept up in the revivals-a yet more substantial figure-the impact of revivals during the Civil War surely was tremendous.

At a local level the numbers were a bit more modest. In The Great Revival of 1863 historian Troy Harman writes:

The revivals from the autumn of 1862 through the spring of 1863 also included large gatherings in the churches of Fredericksburg, which were mostly abandoned by the citizens of that town during the battle. When services were first held in these shell-marked churches in January 1863, the numbers were moderate enough to meet in smaller buildings such as the Presbyterian Church. As the soldier congregations grew, they moved to larger structures such as those of the Methodist church, and finally the largest Episcopal sanctuary. Reverend Bennett recalled a service in the latter facility on March 27, 1863 noting, “At 11:00 [A. M.] we assembled at the Episcopal Church. On this occasion, perhaps 1,500 were in attendance, mostly soldiers. Every grade, from private to Major General was represented.”

The Reverend William Jones D.D (who wrote an excellent account of his time during the war titled Christ in the Camp) recalled his experiences of evangelizing to the troops in his memoirs when he wrote:

Long before the appointed hour the spacious Episcopal church, kindly tended by its rector, is filled - nay, packed-to its utmost capacity-lower floor, galleries, aisles, chancel, pulpit steps and vestibule-while hundreds turn disappointed away, unable to find even standing room… I remember that I preached to this vast congregation the very night before Hooker crossed the river, bringing the battles of Second Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville - that, in my closing appeal, I urged them to accept Christ then and there, because they did not know but that they were hearing their "last invitation," and that sure enough we were aroused before the day the next morning by the crossing of the enemy.

The army was not the only ones suffering. In a personal letter written from Dr. Harry Lovell, who served with the Confederate Army, local citizens and soldiers alike benefited by the presence of this much-needed revival. To his sweetheart the doctor sent:

For the last week or two there has been a good revival going on at the Episcopal Church. Several in which there were a great many soldiers received into the church and baptized. The city presents a baleful appearance. There is no estimating the suffering caused by the shelling of the place. There are hundreds of men who were yard lively who are now reduced to beggary. The poor women and children are starving in every quarter. It is or ought to be a shame in any nation to create such suffering…

Not surprising this local movement spread from the confines of the churches out into the army camps where soldiers would in turn come to town to participate in worship services. Simeon David, a member of the 14th North Carolina Infantry wrote in a letter home that:

There is a very general revival of religion going on in our Brigade at this time, baptizing every day. There are several churches in the surrounding country that our men go to every Sabbath.

Jo Shaner of the Rockbridge Artillery experienced the revival and enthusiastically wrote to his parents about his own spiritual transformation. He said:

I am happy to say that the Lord has been doing great work for us - there has been some 20 or more that has come forward and made a public profession that they intended to follow Christ and I suppose that you both will be glad to hear that I have not been left out of that number. Yes by the help of the Lord I intend to lead a new life - I feel as though I was a new man some 10 or 12 of that number joined the church - Capt Graham also expressed a desire to become a member of the church.

Now what I find to be extraordinary when reflecting on the Great Revival at St. George’s is the fact that amidst all of the occupation and destruction that descended on the city of Fredericksburg, they were one of the few churches to not only remain open - but also pro-active. Like the rest of its community, the bombardment of the town by Federal artillery in December of 1862 had a profound effect on the church and its congregation.

As one of the tallest and most distinctive structures in all of Fredericksburg, St. George’s was particularly threatened by Union cannoneers that were positioned at Stafford Heights, on the bluff just behind the stately Chatham Manor. The towering green steeple had become a target for the gunners and the structure would eventually be hit over twenty-five times during the course of that initial battle. A Union artillerist had recalled a comrade’s attempt to destroy the church’s clock: “An officer of another battery remarked that the first shot he put into the city should pass through the clock; in fact, he proposed to breach the wall in such a way that the clock would fall into the body of the church. He explained that he felt impelled to this act through a sense of predestined responsibility.” (He must have been a Presbyterian like me.)

Of course once they were in occupation of the city, St. George's took on a new role from a Federal target to Federal hospital. One of my very favorite quotes, not only from my book, but also from all quotes I've read in all of my studies of the Civil War, came from another Yankee soldier stationed up in the tower here at St. Georges. He recalled:

Orders came to withdraw the pickets from Fredericksburg. I was in the church steeple, and had been forgotten. When I came down at night, and went to my old position in the rifle pits, I found that my whole company was gone. I was holding the entire town by myself.

As the Federal Army retreated from Fredericksburg and both sides went into winter quarters, local clergy did their part in ministering to the remaining soldiers and citizens. By January and February a religious fervor was spreading. The Religious Herald reported on February 26, 1863 that revival meetings were occurring, “fifty-five consecutive days and nights without regard to weather or other untoward circumstances.” It went on to say that, “Each day, sermons and prayer meetings were virtually hourly affairs from noon until late at night as soldiers became alive with religious animation.”

A typical week of worship included Sunday School, preaching, prayer meetings, Bible classes, inquiry, exhortations, and singing meetings. The evening assemblies, which gained so much attention, were impressive sights indeed. Reverend Bennett recalled, “You behold a mass of men seated on the earth all around you…in the wild woods, under a full moon, aided by the light of side strands.” John H. Worsham, a soldier in the 21st Virginia Infantry, painted a picture of the typical outdoor revival forum, writing:

Trees were cut from the adjoining woods, rolled to this spot, and arranged for seating of at least 2,000 people. At the lower end a platform was raised with logs, rough boards were placed on them, and a bench was made at the far side for the seating of preachers. In front was a pulpit, or desk, made from a box. Around this platform and around the seats, stakes were driven into the ground about ten or fifteen feet apart. On top of them were placed baskets of iron wire, iron hoops, etc. Into these baskets were placed chunks of lightwood, and at night they were lighted and threw a red glare far beyond the confines of the place of worship.

Later in the following spring, Federal forces once again entered the city, much to the dismay of its shell-shocked citizens. The Reverend Alfred Magill Randolph, rector of St. George’s, wrote to his wife from Richmond describing the renewed plight of Fredericksburg’s townsfolk:

My Darling Sallie,

Owing to the condition of the RR and the dread of Yankee Cavalry who are thought to be between here and Ashland trains have not yet been allowed to go to Fredbg—One is expected to go this morning—if so I will go—I am very anxious about our boys—I see that several of Gen Jackson’s staff fell killed or wounded at the time he was wounded—names are not given—we learn, too, that Early’s division had the hardest fighting to do in front of Fredbg and I cannot leave here until I hear from them—it would be duty to them or to Ma—From what I gather the rectory is complete and the Yankee Army beaten and broken, but with terrible loss on our side—Our old town has again been occupied for two days by the enemy and I suppose suffered as before—I have heard as yet nothing from individual friends in the army—

Less than one year later, in April of 1864, Reverend Randolph recalled preaching a ‘revivalesque’ sermon to a large congregation in the upper part of the crippled church. Despite all of the damage and destruction in the downtown area, citizens still managed to traipse through the rubble in order to take communion at periodic Sunday services that were conducted by the reverend and no one else. Attendance at these impromptu services fluctuated from two to three hundred people, and soldiers were often present. Reverend Randolph noted that the possibility of his entire congregation returning to the town in the near future was highly improbable, as provisions were so scarce and the threat of reoccupation remained constantly on the minds of those staying behind.

Of course St. George’s, like Fredericksburg, not only survived the war, but continued to prosper. Your congregation is a testament to that resolve. Here are the meeting minutes regarding the resignation of Rev. Randolph and a collection to aid in remedying the damages caused by quote “shot and shell in the bombardment of December 1862.” In some ways this church was directly responsible for hosting the spiritual conversion of thousands of soldiers who most likely returned home and continued to spread the gospel in their own denominations.

According to historian Troy Harmon:

For the numerous Confederates who participated in revival, their lives changed as they became more sincere about service to country and about personal integrity. Because the issue of where each converted soldier would spend his eternity was settled, each of them perhaps was more apt to risk the dangers of the battlefield. Additionally, it is reasonable to believe that an ample number of them returned home in 1865 to become devout churchgoers and spiritual leaders. Whatever their legacy, these survivors must have reflected back on the two immense revivals in the Army of Northern Virginia, with both amazement and fondness. Most likely, when they pondered the hardships of the war, they shared thoughts of Reverend Wallace when he wrote, “and among the sad memories…the recollection of the great and blessed work of grace that swept through all military grades, from the General to the drummer boy is ‘the silver lining’ to the dark and heavy cloud of war that shook its terrors on our land.”

St. George’s Episcopal Church is therefore not only the site of a great revival, but also a shining example of light amidst one of the darkest periods in American history. The Rev. DD Jones summarized the positive repercussions of this movement when he wrote:

In the midst of the titanic struggle of the American War Between the States, a spiritual war for the souls of men was waged with equal vigor. From 1861 to 1865, many thousands of soldiers professed Christ as their Savior and Lord, and many more were renewed in their commitment to serve God in camp and battlefield.

So what was the historical effect of the Great Revival here at St. George’s? How do we measure its impact? One can look at the results of a battle and immediately see how it shaped the course of the war, yet a religious experience like the one I have discussed today must be measured differently. What is its legacy? Well, its legacy can be traced through the military and civilian believers that I’ve quoted today…converts who recalled this event that occurred almost 150 years ago as being a major transformation in their lives. No doubt those that survived the war continued to practice their newfound faith.

In closing today, I want to share a thought-provoking prayer that is believed to have been found on the body of a dead Confederate soldier. This declaration (to me) personifies the transformation that I mentioned and is a lasting testament to the steadfast belief that may have come about as the result of the Great Revival.

I asked God for strength, that I might achieve,

I was made weak, that I might learn humbly to obey.

I asked God for health, that I might do greater things,

I was given infirmity, that I might do better things.

I asked for riches, that I might be happy,

I was given poverty, that I might be wise.

I asked for power, that I might have the praise of men,

I was given weakness, that I might feel the need of God.

I asked for all things, that I might enjoy life,

I was given life, that I might enjoy all things.

I got nothing that I asked for - but everything I had hoped for.

Almost despite myself, my unspoken prayers were answered.

I am among men, most richly blessed.

[Thank you.]

Updated: Wednesday, 4 April 2012 11:01 AM EDT

Permalink | Share This Post