BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Thursday, 18 March 2010

May I take your coat sir?

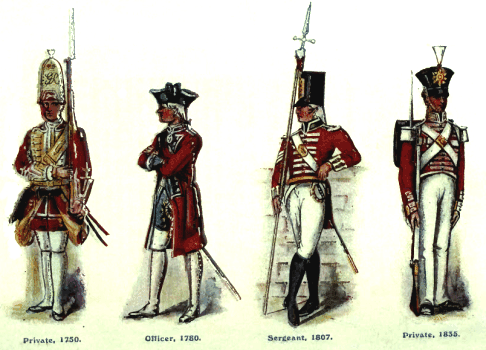

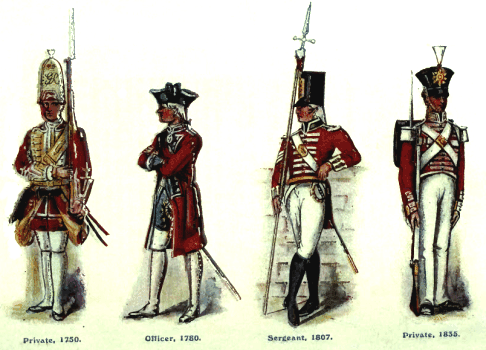

ABOVE: British Army infantry uniforms from 1750 to 1835.

Source: Regimental Nicknames and Traditions of the British Army. (London: Gale & Polden. 1916.)

Today I thought I would share something a little more casual and just for fun… My father has a tremendous collection of records which include a complete set of Bill Cosby’s comedy albums. A good part of my childhood memories include scenes of the family, sitting around the old stereo, listening to some of the funniest bits ever captured on vinyl. One of my favorites is a record titled “Bill Cosby is a Very Funny Fellow Right?” (or something like that). There is a routine from that performance in which Cosby pitches the concept of a referee holding a coin toss at the beginning of a war. He uses the American Revolution as the basis, and after making the right call, the Continentals choose to ‘kick off,’ and add that “We can wear whatever color uniforms we like, and hide behind trees and rocks and stuff, and you British have to wear bright red, and march out in the open in a straight line.” That punch-line stuck with me and even to this day, every time I see a depiction of a Redcoat, that joke enters my mind. What makes it so funny is that it’s true.

Clearly the Brits had far better tailors than the Continentals, but form over function has never worked on the battlefield. In their quest to look their best, many of the King’s finest suffered death by wardrobe. We know this as there have been studies by military historians that cite the affect of heavy and cumbersome uniforms on the army. They have determined that the regulation style uniforms worn by the English troops contributed to needless suffering en route to defeat. There was even an episode of “Battlefield Detectives” on the History Channel in which they concluded that a group of British soldiers who were cut off from any shade or water supplies were beaten by a much smaller force of militia, who pinned them in and simply prevented them from moving (in a siege like state). As the hours passed their enemy fell into a deadly state of heat exhaustion and dehydration. The investigators even went so far as to put two modern-day British Commandos on treadmills, one in the sparse attire worn by the minutemen and the other in a traditional garb worn by English infantry. The Continental fared well, while the Redcoat almost passed out. (Of course the opposite was true in the winter-months and the rebels lightweight gear left much to be desired at places like Valley Forge.)

According to excerpts cited from "History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army" by Maj. R.M. Barnes, “The red coat has evolved from being the British infantryman's ordinary uniform to a garment retained only for ceremonial purposes. Its official adoption dates from February 1645, when the Parliament of England passed the New Model Army ordinance. The new English Army (there was no 'Britain' until the union with Scotland in 1707) was formed of 22,000 men, divided into 12 foot regiments of 1200 men each, 11 horse regiments of 600 men each, one dragoon regiment of 1000 men, and the artillery, consisting of 50 guns. In the United States, "Redcoat" is associated with British soldiers who fought against the colonists during the American Revolution. It does not appear to have been a contemporary expression - accounts of the time usually refer to "Regulars" or "the King's men". Abusive nicknames included "bloody backs" (in a reference to both the colour of their coats and the use of flogging as a means of punishment for military offences) and "lobsters" (most notably in Boston around the time of the Boston Massacre). It is not until the 1880s that the term "redcoat" as a common vernacular expression for the British soldier appears in literary sources, such as Kipling's poem "Tommy", indicating some degree of popular usage in Britain itself. However an isolated earlier use of this term relating to the American War of Independence appears in "The Riflemen's Song at Bennington", an old folk song that supposedly [citation needed] goes back to the 1770s.”

Someone once said that it is “better to look good than to feel good.” Another remarked that you should “always dress for success.” I wonder if the former was an officer in the English Army.

PS. This weekend I’ll be spending Saturday with Mort Kunstler at his Fredericksburg print signing and Sunday I’ll be giving my speech on Mary Ball Washington at the VAFB Women’s Convention. Hopefully I’ll have photos and a video to share next week.

Sunday, 14 March 2010

2010 Event Schedule

I am periodically available for speaking engagements, book signings, radio shows, documentary/television appearances and online chat presentations. Fees and travel expenses are negotiable. Power Point projection requested for speaking events. I will provide the media. *Discounts and/or fees waived for church, military and non-profit groups. Please note that I will only write NEW topics on the Colonial-period. I can present past Civil War talks. See transcripts below. Email for booking info.

March 21, 2010 VA Farm Bureau Women's Conference: Mary Ball Washington, The Mother of the Father of Our Country (Fredericksburg Hospitality House)

June 5, 2010 Book Signing: "Gathering of Eagles" (Winchester Courthouse Museum)

Will return to in 2011.

June 19, 2010 CWHC Muster Banquet: "Jackson's Journey, Stonewall in the Valley" (Lexington Holiday Inn Express)

July 24, 2010 Premiere party: "The Angel of Marye's Heights" documentary.

(Central Rappahannok Regional Library)

September 18, 2010 Screening: "The Angel of Marye's Heights" documentary. (Liberty University Campus)

October 9, 2010 Civil War Author's Book Signing: "Germannafest," Germanna Community College 40th Anniversary Celebration (Locust Grove)

October 21, 2010 "Mary Ball Washington, The Mother of the Father of Our Country" (Stafford County Courthouse Administration Center)

November 13, 2010 Book Signing and Vignettes: "Civil War Author's Day" (Gray Ghost Vineyards and Winery)

Date(s) TBD "The Angel of Marye's Heights" film opening and screenings.

Date TBD NCWLF "Campfires at the Crossroads: Letter Readings" (CW Life Museum)

PAST TRANSCRIPTS:

Richard Kirkland "The Angel of Marye's Heights"

Race Relations at Fredericksburg's Landmark Churches

Backyard History: Lee's Hill Community

Houses of the Holy: Fredericksburg's Churches

The Great Revival in the American Civil War

Faith under Fire: Discipleship during the Civil War

Christ in the Camp by Rev. J. William Jones

Effective Historic Research and Writing

Radio Shows, Chatroom Discussions, and Misc. Events

Commercial and Documentary Appearance samples

Saturday, 13 March 2010

Inaugural Guest Post

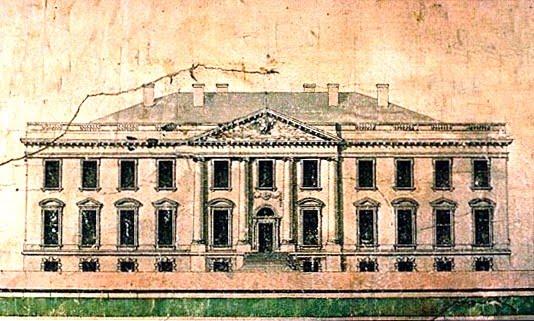

ABOVE: c 1793 Elevation of the original White House, by James Hoban. (MD Historical Society)

One of the new additions to “Blog, or Die.” will be periodic guest posts by fellow historians. Our first candidate and I have collaborated for years over at The Jefferson Project and The Free Lance-Star Town & County. His name is Chris Williams and he is a graduate of VCU, very active politically in the African-American community, and a contributing writer to such award-winning publications as Street Report Magazine. Chris is also an R&B songwriter and producer. His specialty is correlating early American history to today and he has penned several outstanding pieces on Black History Month.

Chris and I have a sincere respect for one another and we often have difficult discussions over issues like racism and historical memory. It was his interpretations of the Founding Fathers that initiated the TJ Project. We don’t always agree, but we glean wisdom from each other’s views and our work is far better for it. Chris recently suggested that we construct some pieces regarding race from the Old America to the New America and in a recent email to me he wrote, “Race is a topic that is almost a societal taboo to speak on, but I have no problem expressing my opinions on it because it's something that we all deal with every day in different ways.”

I asked my friend if he would allow me to share a piece he penned on the origins of the White House. In it he brilliantly integrates the history of the building with the historic presidency that dominated the attention of the day. This article ran just before President Obama’s inauguration and is incredibly fascinating. As the issue of race has become a regular topic here, I can’t think of a better way to kick-off our guest posts than sharing this seldom discussed piece of American history.

THE WHITE HOUSE AND OBAMA

By Chris Williams

FLS (T&C), January 17, 2009

Since its inception, the White House has been a representation of liberty, democracy and independence. What many Americans don't know is how the actual building was constructed and the correlation it has with the heritage of our incoming president, Barack Obama, whose inauguration is Tuesday.

Obama's heritage has intrigued both Republicans and Democrats, but in researching the history of the White House I found striking similarities between the ancestral lineages of the people who designed and built it and of the man who will be residing there next week.

As the story goes, in 1790 the first U.S. Congress approved the Act of Residence to create the permanent seat of the federal government. The act empowered President George Washington to locate America's capital along the Potomac and Anacostia rivers.

It designated Philadelphia as the temporary capital for 10 years until the completion of a presidential residence and a capitol in Washington.

George Washington had a grand vision for the buildings. They would be emblematic of the democracy that America acquired just nine years earlier with the surrender of British troops in the Revolutionary War.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant and Benjamin Banneker devised the original plans for the city of Washington, but those plans were held in abeyance until an architect was found.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson proposed that a national design competition be held to determine the designer of the president's house and Congress' house--the "capitol," the term Virginians used for their statehouse.

The winner of this competition was an Irish architect named James Hoban. Through happenstance, he had met George Washington a year earlier in Charleston, S.C., when Washington was visiting personal friends. Little did they know that a year later they would be joining forces to bring Washington's vision to fruition.

The buildings Hoban designed directly reflected the 18th-century Georgian neoclassical style of the house of the Duke of Leinster in Dublin, Ireland. These designs stood out to Washington because he was fascinated by edifices located in Europe.

"In the last part of the eighteenth century, Americans and the Irish had the same political convictions along with shared strategies in economic development for their countries," according to William Seale, author of "The White House: An American Idea."

It is not known whether this played a role in Washington's choice of Hoban, but his plans were approved in the autumn of 1792 with changes forthcoming a year later.

To proceed with the implementation, the U.S. government planned to import workers from Europe, but recruitment yielded abysmal results. The government then sent out a request for 100 slaves to begin the arduous task of constructing the White House.

The laying of the cornerstone took place on Oct. 13, 1792.

There was a Fredericksburg-area connection to the original construction of the White House. In 1793, enslaved and free blacks from Virginia and Maryland began clearing the forest for the White House and Capitol, digging trenches and ditches and bringing sandstone piece by piece on boats from the Aquia Creek quarry in Stafford County.

They also began hauling lumber and other materials from White Oak Swamp in what is now King and Queen County, and placing cut stones for the walls of the White House.

According to Seale, "City commissioners of the project were concerned that this local source of sandstone couldn't provide the sufficient quantity necessary to produce the White House and the Capitol so they decided to downscale the size of the White House to keep the plans intact. Due to the reduction in size, the White House now in a sense was 'Americanized' because of the loss of the most obvious reference to the Leinster House, which was the high base, but Washington demanded to keep the ground dimensions of the enlarged plans."

Brickmasons worked hand in hand with the stone-masons to provide stability for the structure of the White House.

"The credit for carving the stone for the first White House belonged to two groups of Scottish immigrants who were stonemasons that faced a moratorium from the building industry in England due to the war with revolutionary France," according to Seale.

These two groups of immigrants consisted of members of the Masonic order in Washington and two brothers, John and James Williamson (who were not related to the chief stonemason, Collen Williamson, also from Scotland).

By 1795, Williamson and Hoban no longer saw eye to eye and Williamson was replaced by an English mason, George Blagdin. But it was another Englishman, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, along with Thomas Jefferson, Dr. William Thornton and James Hoban, who saw through the completion of the original White House and Capitol.

Once the construction was finished, the porous sandstone walls were coated with a mixture of lime, rice glue, casein and lead, giving the house its familiar color and name. The first president to inhabit the residence was John Adams in 1800.

Hoban and Latrobe were also responsible for overseeing the reconstruction of the White House after it was burned by the British during the war of 1812.

OBAMA CONNECTION

In this research, I came across some surprising similarities between the lineage of James Hoban and that of President-elect Barack Obama.

Hoban's lineage traces back to the province of Leinster; Obama's great-great-great-grandfather on his mother's side, Falmouth Kearney, also was from the province of Leinster.

Hoban was from County Kilkenny, and Falmouth Kearney was from nearby County Offaly.

It has been well documented that Obama is a distant cousin of President Harry Truman, Vice President Dick Cheney and former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill through their common ancestor, Mareen Duvall.

Obama's English and Scotch-Irish roots can be traced back to the 1650s to Duvall, a wealthy Huguenot merchant who immigrated to Maryland during the mid-17th century.

The fact that Obama's father was African brings into the equation the role of African-Americans in constructing the White House. Their work alongside the Scotch-Irish immigrants was pivotal in laying the foundation and molding the designs for what was variously called the President's Palace, the Presidential Mansion, the President's House, the Executive Mansion and, as it was to be named later by Theodore Roosevelt, the White House.

Each of these disparate groups contributed to crafting a building that will be home to one of its own after the swearing-in of our 44th president on Tuesday night.

President-elect Obama's African, English and Scotch-Irish background make him an anomaly in the sphere of American politics. His election will go down in the time-honored annals of the White House.

Thursday, 11 March 2010

Inspiration in "Charm City"

Today I had the pleasure of traveling to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, where I dined on crab cakes in the shadow of the USS Constellation. Constructed in 1854, this vessel is known as a “sloop-of-war” and was the flagship for the U.S. African Squadron from 1859-1861. During this period she disrupted the African slave trade by interdicting three slave ships and releasing over 700 imprisoned Africans. Armed to the teeth, the Constellation boasts 16 × 8 in (200 mm) chambered shell guns, 4 × 32-pounder (15 kg) long guns, 1 × 20-pounder (9 kg) Parrott rifle, 1 × 30-pounder (14 kg) Parrott rifle, and 3 × 12-pounder (5 kg) bronze boat howitzers. Based on a 1797 frigate design, the USS Constellation was a Civil War–era ship.

I was so inspired by my visit, I am now working on a special post about “The Father of the American Navy,” John Paul Jones. Of all the officers that I have examined from the Revolutionary War, Jones ranks among the top of the list. His performance under fire is considered by many to be second to none and his tactics are still taught by the U.S. Navy today. Captain Jones also has family ties here in Fredericksburg and some of his relatives are buried here. Everyday on the way to the train station I walk past the corner of Lafayette Blvd. and Caroline Street, where a beautifully restored row house stands that belonged to Jones's brother, William Paul. Perhaps I will make some time to stop there one day and discuss the property’s legacy with its owner. Stay tuned for that JPJ post and be sure to visit the USS Constellation the next time you find yourself in Baltimore, craving crab cakes.

On a side-note, please look for my article in this Saturday’s Free Lance-Star Town & County on Mort Künstler’s newest release, The Angel of the Battlefield, as well as the release of my histiography written for the painting itself which depicts Clara Barton’s experience at Chatham. This will be the fourth FLS article I’ve penned on Mort and the fourth painting copy I’ve penned for Mort. He will be coming to town on the 20th for a print signing and I’ll be sure to take some photos to share with you here.

(Photograph by me, via BlackBerry)

Wednesday, 10 March 2010

The emancipating slaveholder

ABOVE: Life of George Washington--The farmer. By Junius Brutus Stearns (Library of Congress).

As my newfound studies into the Revolution continue to expand, one subject that has caught my attention is the extraordinary life and legacy of George Washington. Most of my current reading has been done in preparation for my upcoming presentation on Mary Ball Washington for the VA Farm Bureau Women’s Convention, and for an article that I am writing for Patriots of the American Revolution magazine on Col. Washington and the VA Militia’s experiences in western Pennsylvania. Sources for these projects include Edward G. Lengel’s General George Washington and Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer. Both of these titles are excellent and I am gaining a tremendous wealth of knowledge on our nation’s first commander-in-chief.

Over the years, the majority of my work has focused specifically on the social, political, and religious aspects of our collective history. That is to say NOT the military ones. I have zero expertise in battlefield tactics and leave that subject up to real military historians like Eric Wittenberg and Brooks Simpson. In lieu of manly weapons and strategy, I have chosen to tackle the equally explosive issue of race. Just as my book on Fredericksburg’s churches and PAR feature on Race and Remembrance at Monticello dealt with the complexities and contradictions of slavery, so too are my latest studies into the Founding Fathers. I have written extensively on Thomas Jefferson’s attitudes on the institution of human bondage and I am now examining Washington’s perspective.

I do not consider myself ready to draw any concrete conclusions (yet) on Washington’s struggles over race. That said, I have found the obvious similarities and differences between Jefferson’s and Washington’s racisms to be most intriguing. Both Virginia planters benefited greatly from the institution in their own private enterprise while accumulating and maintaining their family’s wealth on the backs of their slaves. Washington however, ended his life with a mindset that differed from Jefferson’s. The slaves that Washington owned in his own right came from several sources. He was left eleven slaves by his father's will; a portion of his half-brother Lawrence Washington's slaves, about a dozen in all, were willed to him after the death of Lawrence's infant daughter and his widow; and Washington purchased from time to time slaves for himself, mostly before the Revolution.

David Hackett Fischer recently published a piece on Washington titled Born to Lead which contained an excellent sidebar describing this aspect of Washington’s life. Titled The Unapologetic Patrician, it presents a critical portrait of a social snob who begrudgingly maintained slaves until his death:

“Washington grew up among many inequalities, and he accepted most of them. He was very conscious of social rank. A sociable man among his peers, he was at his ease with others of his class and often in their company. From 1768 to 1775, he entertained 2,000 people at Mount Vernon, mostly “people of rank,” as he called them. He deliberately kept others at a distance and advised his manager at Mount Vernon always to deal that way with inferiors. “To treat them civilly is no more than what all men are entitled to,” Washington wrote, “but my advice to you is, to keep them at a proper distance; for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you sink in authority.” Washington had been taught to treat people of every rank with civility and “condescension,” a word that has changed its meaning in the modern era. In Washington’s world, to condescend was to treat inferiors with decency and respect while maintaining a system of inequality.

His world was also a hierarchy of wealth, and Washington acquired a large share of it. When his brother died, he became the master of Mount Vernon at the age of 22, leasing it from his sister-in-law, then owning it outright. At 36, he married Martha Parke Custis, a very beautiful and gracious woman and one of the richest widows in Virginia. By skillful management and good luck, his property increased rapidly before the Revolution. Public service diminished his wealth, and he was forced to sell large tracts of land to pay the expenses of his presidency, but even with that burden, he built one of the largest family fortunes in America, with a net worth of more than a million dollars. In 1799, his and his wife’s estates included many thousands of acres and 331 slaves.

Part of his world was hierarchy and race. In his early years, Washington owned many slaves and actively bought and sold them. Before the Revolution, he shared the attitudes of his time and place and fully accepted slavery, but after 1775, his thoughts changed rapidly. He began to speak of slavery as a great evil, and by 1777, he wrote of his determination to “get clear” of it. After much thought and careful preparation, he emancipated all of his slaves in his will.” (Bold emphasis added.)

It appears that Washington’s conscience was deeply troubled in his later years. His determination to free his slaves was likely a way of easing the burden of guilt. Unlike Jefferson, Washington freed all of his slaves upon his (and his wife’s) death, making no distinction between them. Every one was granted liberty regardless of their age, position, or stature within the household. Jefferson only freed certain slaves when he passed away and many more were sold off by his heirs to cover the immense debt that he had incurred while building Monticello. One could even say that Jefferson relinquished his slaves because he had to, while Washington appears to have done so because he wanted to. Here is an excerpt from Washington’s will that frees his slaves and commends them for their service (Note: the < > denotes where text was illegible, but can be assumed):

<Ite>m Upon the decease <of> my wife, it is my Will & desire th<at> all the Slaves which I hold in <my> own right, shall receive their free<dom>. To emancipate them during <her> life, would, tho' earnestly wish<ed by> me, be attended with such insu<pera>ble difficulties on account of thei<r interm>ixture by Marriages with the <dow>er Negroes, as to excite the most pa<in>ful sensations, if not disagreeabl<e c>onsequences from the latter, while <both> descriptions are in the occupancy <of> the same Proprietor; it not being <in> my power, under the tenure by which <th>e Dower Negroes are held, to man<umi>t them. And whereas among <thos>e who will recieve freedom ac<cor>ding to this devise, there may b<e so>me, who from old age or bodily infi<rm>ities, and others who on account of <the>ir infancy, that will be unable to <su>pport themselves; it is m<y Will and de>sire that all who <come under the first> & second descrip<tion shall be comfor>tably cloathed & <fed by my heirs while> they live; and that such of the latter description as have no parents living, or if living are unable, or unwilling to provide for them, shall be bound by the Court until they shall arrive at the ag<e> of twenty five years; and in cases where no record can be produced, whereby their ages can be ascertained, the judgment of the Court, upon its own view of the subject, shall be adequate and final. The Negros thus bound, are (by their Masters or Mistresses) to be taught to read & write; and to be brought up to some useful occupation, agreeably to the Laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, providing for the support of Orphan and other poor Children. and I do hereby expressly forbid the Sale, or transportation out of the said Commonwealth, of any Slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever. And I do moreover most pointedly, and most solemnly enjoin it upon my Executors hereafter named, or the Survivors of them, to see that th<is cla>use respecting Slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled at the Epoch at which it is directed to take place; without evasion, neglect or delay, after the Crops which may then be on the ground are harvested, particularly as it respects the aged and infirm; seeing that a regular and permanent fund be established for their support so long as there are subjects requiring it; not trusting to the <u>ncertain provision to be made by individuals. And to my Mulatto man William (calling himself William Lee) I give immediate freedom; or if he should prefer it (on account of the accidents which ha<v>e befallen him, and which have rendered him incapable of walking or of any active employment) to remain in the situation he now is, it shall be optional in him to do so: In either case however, I allow him an annuity of thirty dollars during his natural life, whic<h> shall be independent of the victuals and cloaths he has been accustomed to receive, if he chuses the last alternative; but in full, with his freedom, if he prefers the first; & this I give him as a test<im>ony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War. <end>

A detailed listing of Washington’s slaves is also available online at The Papers of George Washington. More on this subject to come.

Newer | Latest | Older