|

|

Good afternoon

folks. It is an honor and a

privilege to have the opportunity

to speak to you this afternoon. I

would like to thank each and

every one of you for coming. I

would also like to thank the

entire staff here at the Manassas

Museum for their invitation and

hospitality. Today's presentation

is titled "The Great Revival."

I've specialized in the study of

Christianity in the War Between

the States for the last 5 years

or so and my goal today is to

share some uplifting and positive

stories that took place during

one of the most tragic times in

our nation's history.

|

spacer

My talk today will be

featuring excerpts from studies I've done

for The Jackson Society as well as my

devotional 'The Southern Cross: 50

inspirational stories about faith under

fire.' These stories will feature the

common soldier, two officers, a

politician, and a priest. All had a

significant contribution to the rise of

religion in the Civil War. I promise not

to go too long and I will be happy to take

any questions you may have. I will also be

signing discounted copies of this book

today in the gallery.

Let's begin by briefly

looking at the subject of faith and its

impact during one of the darkest periods

in American history. Religion in America

during the 19th-Century, more

specifically, Protestantism, was a major

brick in the foundation of the nation.

Religion played a vital role politically,

socially, and of course spiritually.

Therefore it is no surprise that faith

remained a welcome companion to both

soldiers in the field and citizens on the

home front. It is my opinion that

Christianity was also a major factor

during the reconciliation and

reconstruction years that followed the

war.

To this day, casualties

from the Civil War (620,000+) still exceed

our country's losses in all other military

conflicts. From 1861 to 1865, both sides

suffered tremendous fatalities (almost 2%

of the population was lost) and the

subsequent damage to the country's

infrastructure cost millions to rebuild.

Perhaps if either army could have foreseen

the tragedy that would befall them, a

compromise may have been offered in place

of musket fire.

Still, one cannot deny the

fact that one of the positive

repercussions of the War Between the

States was the number of soldiers that

were baptized in the field. Many troops

became 'born-again' during the later years

of the war as things became more desperate

and hopeless. The romance and pageantry

that had once attracted volunteers by the

thousands at the beginning of the conflict

wore away as the blood-soaked killing

fields spread like a cancer across the

country. From firesides of the Eastern

Campaign here in Virginia to the army

campsites of Tennessee, soldiers came to

Christ by the thousands.

However, according to some

accounts, religion did not accompany many

soldiers at the start of the war. The

magazine Christianity Today recalled the

trials and tribulations with living a

Godly life while on campaign. It stated:

"Day-to-day army life was so boring that

men were often tempted to 'make some

foolishness,' as one soldier typified it.

Christians complained that no Sabbath was

observed. General Robert McAllister, an

officer who was working closely with the

United States Christian Commission,

complained that a 'tide of irreligion' had

rolled over his army 'like a mighty

wave.'" Frankly you had thousands of young

men who had never left home, unsupervised,

and "off their leashes" so to

speak.

Fortunately, as the war

progressed, a movement referred to as "The

Great Revival" took place in the South.

Beginning in the fall of 1863, this event

was in full progress throughout the Army

of Northern Virginia. Approximately 7,000

rebel soldiers in Robert E. Lee's force

were converted before the revival was

interrupted by General U.S. Grant's attack

in May of 1864.

Dr. Gardiner H. Shattuck,

Jr., author of 'A Shield and Hiding Place:

The Religious Life of the Civil War

Armies,' reports that "The best estimates

of conversions in the Union forces place

the figure between 100,000 and 200,000

men-about 5-10 percent of all individuals

engaged in the conflict. In the smaller

Confederate armies, at least 100,000 were

converted. Since these numbers include

only 'conversions' and do not represent

the number of soldiers actually swept up

in the revivals-a yet more substantial

figure-the impact of revivals during the

Civil War surely was tremendous."

Throughout the war the

church was repeatedly called upon to meet

many new challenges that came with a

divided nation. Protecting the sanctity of

religious practices remained a top

priority for those who were extremely

concerned about the repercussions of the

wartime climate. First and foremost was

the inevitable splitting of the

denominations following the South's

secession. And although there appeared to

be no immediate hostilities harbored by

Christian leaders on either side, the fact

remained that the political split in the

country - also split the church. This had

a profound affect on virtually every

aspect of their operations.

For example, up until the

outbreak of the Civil War, the American

Bible Society, based in New York, handled

the production and distribution of most

Protestant-based materials including

Bibles and tracts. After the conflict

began, an entirely new system had to be

formed in order to meet the needs of the

Southern congregations. Many of these

dilemmas were addressed in the minutes of

the Presbyterian Church's General

Assembly.

One major point addressed

the need to establish a new chapter of the

Bible Society to shoulder the task of

producing and distributing religious

materials in the Confederate States.

Privatized organizations representing a

multitude of denominations stepped forward

printing and distributing gospel tracts in

the field. Another concern pertained to

the issue of camp worship and the negative

affects of military operations on the

Sabbath.

Perhaps most surprising,

most armies during the War Between the

States did not commonly deploy with

embedded clergy. Many Christian commanders

in the field recognized the need for

spiritual strengthening and that a healthy

soul meant healthy troops. One of the most

outspoken on this crisis was a man near

and dear to my heart and of course the

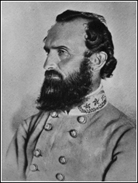

Manassas area, Confederate General Thomas

J. Jackson.

|

|

"Old Jack" (later

christened 'Stonewall') was one

of the South's most pious

believers and the first

high-ranking officer to

personally lobby for chaplains,

arguing that a soldier's mental

state of mind directly affected

his ability to perform on the

battlefield. Jackson also

regularly put forth an effort to

introduce this philosophy to the

rest of the southern army. After

realizing a lack of participation

in the war effort by the church,

Jackson sent a letter to the

Southern Presbyterian General

Assembly, petitioning them for

support.

|

spacer

In it he stated, "Each

branch of the Christian Church should send

into the army some of its most prominent

ministers who are distinguished for their

piety, talents and zeal; and such

ministers should labor to produce concert

of action among chaplains and Christians

in the army. These ministers should give

special attention to preaching to

regiments which are without chaplains, and

induce them to take steps to get

chaplains, to let the regiments name the

denominations from which they desire

chaplains selected, and then to see that

suitable chaplains are secured." He added,

"A bad selection of a chaplain may prove a

curse instead of a blessing."

Despite the lack of

readily available clergymen in the early

Confederate Army, Jackson appointed a

personal minister to his staff and

maintained daily prayer rituals whether in

camp or on the march. Whenever possible, a

strict schedule of morning and evening

worship on the Sabbath, as well as

Wednesday prayer meetings, was adhered to

at all costs. One of our local

Fredericksburg preachers, the chaplain

Reverend Beverly Tucker Lacy routinely led

the services, which were often attended by

General Lee and his staff.

As the courageous

reputation of the "Stonewall Brigade"

continued to grow, so did its quest for

salvation. Jackson's own passion for

sharing the Word and steadfast faith

ultimately inspired his men to rise to the

occasion and his beliefs became infectious

throughout the ranks. By putting his trust

in God, he was able to inspire those under

him to achieve victory in the face of

defeat. With total confidence, he

routinely bragged of their bravery saying,

"Who could not conquer with such troops as

these?"

In addition, Reverend

Lacy's energizing speeches quickly became

a popular event for saved and unsaved

soldiers alike, who attended his sermons

by the thousands. Jackson recalled one

particular event that summarized the

success of their ministry. He wrote, "It

was a noble sight to see there those, who

led our armies to victory and upon whom

the eyes of the nation are turned with

admiration and gratitude, melted in tears

at the story of the cross and the

exhibition of the love of God to the

repenting and return sinner."

Thanks to the good

general's efforts and example, the

Confederate Army soon began assigning

chaplains to accompany its flocks into the

field. Some of these shepherds even went

so far as to participate in the fight, but

most were stationed at camp for weekly

rituals and ceremonies before and after

the battle.

As expected, there were

predominantly Protestant preachers in the

South. The Catholic contingency was larger

in the North's ranks, mostly due to the

large population of immigrants. Regardless

of the off-balance numbers of Protestants

and Catholics, denominations were not

important in the eyes of Jackson or his

peers.

He specifically addressed

this issue by stating that,

"Denominational distinctions should be

kept out of view, and not touched upon.

And, as a general rule, I do not think a

chaplain who would preach denominational

sermons should be in the army. His

congregation is his regiment, and it is

composed of various denominations. I would

like to see no question asked in the army

of what denomination a chaplain belongs

to; but let the question be, Does he

preach the Gospel?"

Fortunately, clergy soon

after became an integral part of military

life that grew into a mandatory asset for

an army, especially on deployment. Even

today, the chaplains are still out in the

field, providing our troops with spiritual

nourishment. I have been contacted by

several military clergymen over the years,

most are interested in using my religious

bio on Thomas Jackson and the Bible Study

curriculum that was developed with it. All

of them cite Stonewall as a major

influence on how they conduct themselves.

Several have written their doctoral thesis

on Jackson's piety.

Another little known fact

about Stonewall's legacy was that he and

his wife helped to establish the first

African-American Sunday School in

Lexington. To this day the controversial

subject of Jackson's contradictory role in

the religious education of both free and

slave blacks is debated by historians

abroad. My very good friend and the man

who wrote the Foreword to 'The Southern

Cross' Richard Williams Jr. has written a

critically acclaimed book on the subject

titled 'Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man's

Friend.' I recommend it highly. The

research is extraordinary and you can

judge Jackson's motivations for

yourself.

Now contrary to some

popular beliefs down here in the South,

there were in fact, influential believers

in the blue uniform. Perhaps the only

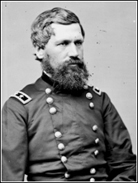

Union commander with an equally infectious

faith as that of Jackson was none other

than "The Christian General" Oliver

Howard. If I ever write a book on a

Yankee, this is the guy I'll do.

|

|

General Howard

could just as easily been

attending camp service in a gray

uniform - if not for politics, a

strong opinion against slavery,

and a sense of duty toward

preserving the Union. Even in

battle Howard was as much a moral

crusader as a warrior, insisting

that his troops attend prayer and

temperance meetings. A recent PBS

documentary summed up the life of

Oliver Howard perfectly when it

said, "Throughout his long

military career, Oliver Howard

gained victory by the force of

his moral convictions, as often

as by force of arms."

|

spacer

In 1857, Howard was a

full-time soldier who was deployed to

Florida for the Seminole Wars. It was

there that he experienced a conversion to

evangelical Christianity and considered

resigning from the army to become a

minister. His religious proclivities would

later earn him the nickname "the Christian

general." On the outbreak of the Civil

War, Howard, an opponent of slavery,

resigned his regular army commission and

became colonel of the Third Maine

Volunteers in the Union Army. Much like

Jackson, Howard made spiritual

strengthening a daily part of his troop's

regiments.

Unfortunately, Howard's

motivational efforts did not always

transpire on the battlefield in the same

manner that it did for Jackson's brigades.

At the Battle of Fair Oaks (June1862) he

was wounded twice in the right arm. The

second wound shattered his bone near the

elbow. It was amputated, and Howard spent

two months recovering from his wounds

before coming back. He was also given the

Medal of Honor as a result of his own

gallantry.

According to an August

1864 issue of Harper's Weekly: "General

Howard has lost his right arm in his

country's service. It used to be a joke

between him and Kearney, who had lost his

left arm, that, as a matter of economy,

they might purchase their gloves together.

One of Howard's most significant moments

(in the field) came at Gettysburg, where

he assumed command of Reynolds troops

after he was killed."

After the war, he was

appointed head of the Freedman's Bureau,

which was designed to protect and assist

the newly freed slaves. In this position,

Howard quickly earned the contempt of

white Southerners and many Northerners for

his unapologetic support of black suffrage

and his efforts to distribute land to

African-Americans. He was also fearlessly

candid about expressing his belief that

the majority of white Southerners would be

happy to see slavery restored.

He even championed freedom

and equality for former slaves in his

private life, by working to make his elite

Washington, D.C., church racially

integrated and by helping to found an

all-black college in the District of

Columbia, which was soon named Howard

University in his honor. Oliver Howard was

essentially a civil rights activist,

before there was a civil right's movement.

Perhaps no other war veteran rallied for

the assimilation of freed blacks more than

he.

In addition, Howard was

active in Indian engagements and

subsequent relations in the West and is

remembered as a man of his word and of

strong moral convictions. As was quite

common, many of the surviving commanders

of the Civil War became "celebrities" in

the public eye, and they often signed

autographs. Howard routinely signed his

"The Lord Is My Shepard."

Much like Thomas

"Stonewall" Jackson was in the South,

Oliver "O" Howard is to be credited for

his evangelistic efforts on behalf of the

North, in addition to his activism on

behalf of all minorities living in the

U.S. at the time. He was a man of God who

ultimately became a man of the people -

ALL people - regardless of the color of

their skin. Yes Oliver O' was indeed a

damn Yankee, but he was a damn good one

too.

|

|

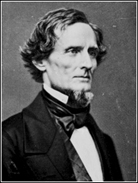

Next up is a

gentleman you'll all recognize.

Every road here in the Old

Dominion is named after him. Of

course this is the one and only

Jefferson Davis. Now J.D. here is

one of those guys who many people

recall incorrectly. And a little

known fact that I will share with

you today, showcases a major

contribution he had to religion

and politics, not only in the

Confederate States of America,

but also later in the reunited

government of the US. Despite

popular belief, he did not

'officially' volunteer for the

position of president in the

Confederate States.

|

spacer

He had a successful track

record as a politician prior to the war

and was nominated and later appointed. In

fact, there is a story on his History

Channel bio that tells of a messenger

riding up to the front yard of Davis'

residence and informing him that he was

just made president of the seceded states.

He did not necessarily want the job at

first, but he took it as he was a man of

duty. He had been what most historians

today consider to be one of the greatest

Secretaries of Defense in the history of

America. At the time the position was

called the Secretary of War. It was there

where Davis established many of the roots

of the Department of Defense that we have

today.

He revolutionized the

Navy, initiated competitive weapons

development and defense contracting. He

also developed new tactics to go with the

new weapons and was a tremendous

taskmaster. Unfortunately, he would not

have the same success as the Confederacy's

Commander and Chief.

Davis was a poor

protestant, a man of humble origins, who

began his formal education at a small,

one-room, log cabin school in the back

woods of Mississippi. (similar to his

counterpart U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

from Illinois.) Two years later, his

family moved and he entered the Catholic

school of Saint Thomas at St. Rose Priory,

which was operated by the Dominican Order

of Kentucky.

At the time, Davis was the

only Protestant student in the entire

institution, but his own acceptance, as

well as an introduction to a different

denomination, made a lasting impression on

the Episcopalian. Later, as a West Point

graduate, Davis prided himself on the

military skills he had gained in the

Mexican-American War as a colonel in a

volunteer regiment and as U.S. Secretary

of War under President Franklin Pierce.

After rising to the highest chair in the

newly established Confederate government,

Davis made a concerted effort to bridge

the spiritual and social gaps between

citizens of different faiths.

During the 19th Century,

Catholics and Jews were often held in

contempt and discriminated against by the

country's Protestant majority. President

Davis did not share this sentiment and

following his appointment to power, he set

a precedent when he assembled the first

administration in American history that

integrated Protestants, Catholics and

Jews. This included his Secretary of

State/ Secretary of War/Attorney General:

Judah P. Benjamin (Jewish) and Secretary

of the Navy: Stephen R. Mallory

(Catholic).

Davis' unorthodox and

courageous decision went against all

previous political practices and

ultimately sent shockwaves through all of

the county's governing bodies, as not even

his contemporary, Abraham Lincoln, had

appointed anyone other than Protestants to

a high office.

In his article 'Jefferson

Davis, Religion and the Politics of

Recognition,' D. Jason Berggren stated

that, "Davis practiced the politics of

recognition by appointing individuals

identified with persecuted religious

minorities. In this regard, contrary to

conventional wisdom, Jefferson Davis was a

remarkable president, a president ahead of

his time." In the end, Davis was simply a

disciple who respected other

Christian-Judea faiths and gave them

legitimacy in the community that he

governed. He once said, "Never be haughty

to the humble; never be humble to the

haughty." Haughty of course meaning

arrogant.

This kind of humbleness

and acceptance of fellow believers of

different theologies bred a fellowship

that spread among the southern states. It

took guts for Davis to do that and our

politicians today seem more bent on

dividing the country's believers instead

of bringing them all to the table. His

choice was very risky and very unpopular,

but it was the right thing to do.

Now I will caveat that

statement by adding that there was an

undeniable hypocrisy that still existed

within the Confederate government by

rallying in the pursuit of freedom and

independence for the white population,

while simultaneously supporting the

institution of slavery.

That said, when examining

the role that faith played in both free

and enslaved societies, it is reaffirming

to know that there were still positive

changes that later benefited all creeds

and colors.

So although he ultimately

'lost' the war and the country, Jefferson

Davis' courage to bridge the gap between

faiths did have a positive impact on all

administrations that followed him even to

this day. Keeping with that theme of

different denominations, let's look at the

last individual that I will be speaking

about today.

Everyone I've talked about

so far has been a Protestant, but I want

to finish today's talk looking at a

Catholic who truly personified the term

'prayer warrior.'

|

|

According to

Catholic doctrine, one of the

most important duties that a

priest administers is the act of

"Last Rites," which is a form of

absolution that is given to a

dying person. In time of war,

this provides a problem as men

obviously fall on the battlefield

without having a priest nearby.

In order to compensate for this

absence, Catholic chaplains would

perform a universal form of this

prior to the battle. Much like

their Protestant peers, the

Catholics would gather together

on the eve of (or hours before)

an anticipated engagement, but

their ceremony would include a

"Last Rites" ritual that would

prematurely absolve them in the

event that they were

killed.

|

spacer

This Mass was extremely

important to brigades that were made up of

immigrants such as the Irish and German

contingencies. Perhaps the most famous of

these was "The Irish Brigade," who

deployed with Father William Corby.

On The American Civil War

web site, they describe his invaluable

service: "For many Civil War soldiers,

both North and South, religion served to

provide hope and meaning given what they

endured during this bloody, violent

conflict. When possible, men of the church

would take an active role in lending such

to the troops both during times of

idleness and of combat." They add, "The

Reverend Father William Corby, chaplain to

the Union's Irish Brigade among others,

extended general absolution to all

soldiers, Catholic and non-Catholic alike.

He was also known to administer Last Rites

to the dying on the field while under

fire.

Prior to the conflict in

the Wheatfield on the second day of the

Battle of Gettysburg, he offered general

absolution to the Irish Brigade. Despite

the loss of 506 of their men during that

day's battle, one soldier stated that,

because of Father Corby, "He felt as

strong as a lion after that and felt no

fear although his comrade was shot down

beside him." Not the only example of

heroism by people of the clergy, Chaplain

William Hoge ignored the Union Blockade to

bring Bibles to Southern soldiers."

Father Corby was born in

Detroit on October 2, 1833 to Daniel, a

native of King's County, Ireland and

Elizabeth, a citizen of Canada. Daniel

became a prominent real estate dealer and

one of the wealthiest landed proprietors

in the country. He helped to found many

Detroit parishes and aided in the building

of many churches. His son William was

educated in the common schools until he

was sixteen and then joined his father's

business for four years. Realizing that

William had a calling to the priesthood

and a desire to go to college, Daniel sent

him and his two younger brothers to the

ten year old university of Notre Dame in

South Bend, Indiana. The Congregation of

the Holy Cross staffed the school then, as

now.

After graduation, Corby

returned to the school as a faculty

member. During the Civil War, he

volunteered his services as a chaplain in

the Union Army at the request of Father

Sorin, who was the Superior-General of the

Congregation of the Holy Cross. Corby

resigned his professorship at Notre Dame

and was assigned as chaplain to the 88th

New York Volunteer Infantry in the famed

Irish Brigade of Thomas Francis Meagher.

It has been written that he boarded the

train with a song on his lips - singing,

"I'll hang my harp on a willow tree. I'm

off to the wars again: A peaceful home has

no charm for me. The battlefield no

pain."

For the next three years,

Father Corby ministered to the troops with

great enthusiasm. This made him popular

with the men. According to the Catholic

Cultural Society, "Chaplains, like

officers, won the common soldiers' respect

with their bravery under fire. Father

Corby's willingness to share the hardships

of the men with a light-hearted attitude

and his calm heroism in bringing spiritual

and physical comfort to men in the thick

of the fighting won him the esteem and the

friendship of the men he served.

Frequently under fire, Corby moved among

casualties on the field, giving assistance

to the wounded and absolution to the

dying. For days after the battles, he

inhabited the field hospitals to bring

comfort to men in pain."

Known for their glorious

(and ultimately disastrous) charge at

Fredericksburg, the Irish Brigade also

made a gallant stand at Gettysburg, where

their priest has been forever memorialized

in a modest statue that stands near the

Pennsylvania Monument. The CCS recalls

this as the defining moment for BOTH the

brigade and their chaplain: "Before the

Brigade engaged the Confederate soldiers

at a wheat field just south of Gettysburg,

Father William Corby, in a singular event

that lives in the history of the Civil

War, addressed the troops.

Placing his purple stole

around his neck, Corby climbed atop a

large boulder and offered absolution to

the entire unit, a ceremony never before

performed in America. Kohl, editor of

Corby's memoirs, tells us that Father

Corby sternly reminded the soldiers of

their duties, warning that the Church

would deny Christian burial to any who

wavered and did not uphold the flag. The

members of the Brigade were admonished to

confess their sins in the correct manner

at their earliest opportunity."

After repenting in the

eyes of their Lord, the Irish Brigade

plunged forward into battle and were met

with a massive volley of fire from the

Confederate forces. At the end of the day,

198 of the men whom Father Corby had

blessed had been killed. A tragedy? Yes.

But it was dulled by the fact that the

departed heroes had been absolved and

blessed prior to the engagement.

This surely made the

family and friends of the dead, a little

less sad, believing that their loved ones

received the promise of salvation. Father

Corby's presence was invaluable and a

great comfort to all who attended his

services. He is perhaps, the most famous

and revered Catholic priest of the entire

Civil War.

Following the war, Father

Corby returned to Notre Dame in 1865 where

he was made vice president. Within a year,

Corby was named president. At the end of

his term at Notre Dame 1872, Father Corby

was sent to Sacred Heart College. He

returned to Notre Dame as president in

1877 where he became known as the "Second

Founder of Notre Dame" for his successful

effort to rebuild the campus following a

fire. Later he became Assistant General

for the worldwide order.

Father Corby wrote a book

of his recollections, entitled "Memoirs of

Chaplain Life." He stated, "Oh, you of a

younger generation, think of what it cost

our forefathers to save our glorious

inheritance of union and liberty! If you

let it slip from your hands you will

deserve to be branded as ungrateful

cowards and undutiful sons. But, no! You

will not fail to cherish the prize-- it is

too sacred a trust-- too dearly

purchased."

He died in 1897, and as he

was being buried, surviving veterans of

the Grand Army Of The Republic are said to

have sang this song: "Answering the call

of roll on high. Dropping from the ranks

as they make reply. Filling up the army of

the by and by." Today Father Corby remains

the most revered and remembered priest of

the Civil War.

|

|

In closing today,

and in honor of the museum's

newest exhibit on the life of the

Civil War soldier, I would like

to share a quote from a wonderful

and thought provoking prayer that

is rumored to have been found on

the body of a dead Confederate

Soldier.

It personifies in

my opinion the essence of how

important of a role faith played

in the life and death of our boys

in blue and in gray. It

says:

|

spacer

I asked God for strength,

that I might achieve,

I was made weak, that I might learn humbly

to obey.

I asked God for health,

that I might do greater things,

I was given infirmity, that I might do

better things.

I asked for riches, that I

might be happy,

I was given poverty, that I might be

wise.

I asked for power, that I

might have the praise of men,

I was given weakness, that I might feel

the need of God.

I asked for all things,

that I might enjoy life,

I was given life, that I might enjoy all

things.

I got nothing that I asked

for - but everything I had hoped for.

Almost despite myself, my unspoken prayers

were answered.

I am among men, most

richly blessed. (Amen)

Thank you all very

much.

Are there any questions?

|