Here is a PDF of the official announcement from The History Press for my fifth and newest book, The Civil War in Spotsylvania: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads.

Updated: Monday, 19 October 2009 1:09 PM EDT

Permalink | Share This Post

Here is a PDF of the official announcement from The History Press for my fifth and newest book, The Civil War in Spotsylvania: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads.

This will be the third, and perhaps last post before I start my new Technical Writer position with the U.S. Marshals. As I adjust to my commute, I hope to blog from the train via my Blackberry, but we’ll see how that goes. One of the many things that immediately impressed me about this outfit was their obvious dedication to preserving their own legacy. History really matters to the U.S. Marshals and the moment you enter their headquarters, you are greeted by a large statue of Wyatt Earp. At my panel interview, I was tested on my knowledge of the organization. Fortunately, I had prepped myself by spending some time on their website. Who knows? Maybe someday I'll write a book on the subject.

This will be the third, and perhaps last post before I start my new Technical Writer position with the U.S. Marshals. As I adjust to my commute, I hope to blog from the train via my Blackberry, but we’ll see how that goes. One of the many things that immediately impressed me about this outfit was their obvious dedication to preserving their own legacy. History really matters to the U.S. Marshals and the moment you enter their headquarters, you are greeted by a large statue of Wyatt Earp. At my panel interview, I was tested on my knowledge of the organization. Fortunately, I had prepped myself by spending some time on their website. Who knows? Maybe someday I'll write a book on the subject.

Much like the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Marshals Service wants their people at every level to fully appreciate the history of those who came before them. As the oldest federal law enforcement agency in the United States, they have apprehended more fugitives than all other law-enforcement agencies combined. As a historian, I love the fact that this group embraces their heritage and goes to great lengths to instill the same values of those who came before them. The list of noteworthy U.S. Marshals is a long one and includes familiar names such as Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok, and even Frederick Douglass (I never knew that.) Two Confederate Generals also wore the silver-star, Benjamin McCulloch, U.S. Marshal for Eastern District of Texas; who became a brigadier general, and Richard Griffith, who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Savage's Station during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign.

Griffith is a particularly interesting character in southern Civil War history as he was originally from Pennsylvania. He was born in Philadelphia and graduated from Ohio University before moving to Vicksburg, Mississippi. During the Mexican War, Griffith served as an infantryman with the 1st Mississippi Rifles. It was there where he met and became close friends with an up-and-coming colonel named Jefferson Davis. After the war Griffith left the army for civilian life and worked as both a banker and a U.S. Marshal. He also held the rank of brigadier general in the Mississippi State Militia.

At the outbreak of the War Between the States, Griffith sided with the Confederacy and was immediately appointed as a colonel in the 12th Mississippi Infantry. One year later he was promoted to brigadier general and put in command of four Mississippi regiments that became part of Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder’s division. Griffith saw action at the Seven Days Battles near the Confederate capital of Richmond. During that engagement he was mortally wounded in his thigh by a shell fragment. As he died he was recorded to have said, “If only I could have led my brigade through this battle, I would have died satisfied.”

According to his bio: The loss of General Griffith was much lamented by many, including his long-time friend Jefferson Davis. Of the fighting at Savage Station he wrote, “Our loss was small in numbers, but great in value. Among others who could ill be spared, here fell the gallant soldier, the useful citizen, the true friend and Christian gentleman, Brigadier General Richard Griffith. He had served with distinction in foreign war, and, when the South was invaded, was among the first to take up arms in defense of our rights.” Later in the war, a group of soldier-musicians called “The McLaws Minstrels,” serving under Lafayette McLaws and formerly under General Griffith, would play at a theater in Fredericksburg. They charged a modest admission fee, the proceeds from which were used to erect a monument in the Mississippi State Capitol in honor of their fallen commander.

Today, Brig. Gen. Richard Griffith is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Jackson, MS.

As the start date for my new job with the U.S. Marshals approaches, I have found myself eagerly anticipating the many changes that will now affect my work day. Perhaps the biggest adjustment will come in the form of the commute. Not one to sit still much, I have been looking at constructive ways to pass the time on the train. In addition to reading, music has always been a great traveling companion of mine. Recently I re-discovered Classical music. While in school, I developed a serious liking to instrumental film soundtracks that led to my appreciation of the master composers. Over the years, I moved away from the genre, but after coming back, I feel a renewed vigor and appreciation for it. Perhaps I'm finally cool with being un-cool. (Apparently this is nothing new, as my kids have known I'm a geek for years.)

As the start date for my new job with the U.S. Marshals approaches, I have found myself eagerly anticipating the many changes that will now affect my work day. Perhaps the biggest adjustment will come in the form of the commute. Not one to sit still much, I have been looking at constructive ways to pass the time on the train. In addition to reading, music has always been a great traveling companion of mine. Recently I re-discovered Classical music. While in school, I developed a serious liking to instrumental film soundtracks that led to my appreciation of the master composers. Over the years, I moved away from the genre, but after coming back, I feel a renewed vigor and appreciation for it. Perhaps I'm finally cool with being un-cool. (Apparently this is nothing new, as my kids have known I'm a geek for years.)

Until recently, I always listened to Talk Radio, but that forum had become so politically charged and divisive, I could hardly stand a minute of it. Frankly, it made me angry, so one day I tuned into a local Classical station as I traveled to and from work. Amazingly, the music had a tremendous calming affect on me and I began to feel incredibly relaxed and replenished. When I got home, I loaded my entire iPod with my Classical CD collection including symphonies from Mozart, Tchaikovsky, and Handel. It was as if I was reacquainting myself with an old friend. I am fortunate that Virginia gets one of the top Classical public radio stations in the country WETA 90.9 FM. Now I find myself listening to Classical as I write and I think my output is improving.

I hope that my musical knowledge and tastes will continue to evolve as I spend more time listening to this style. I know I have plenty of "high-brow" readers out there, so please feel free to recommend any concertos, sonatas or symphonies that you think I may enjoy. The historian in me is especially interested in compiling the kinds of tunes that our Founding Fathers enjoyed. I wonder what was on Jefferson's iPod?

I wanted to share it then, but there were some procedures that still needed to take place. Without getting into any specific-details, I can now say that I have accepted a full-time position as a Technical Writer for the U.S. Marshals. I could not be more excited about this career move and I ask that you be patient in the coming weeks as I adjust to this new job. I think it’s fair to say that I will not be blogging as frequently in the coming weeks, but I promise to make my posts worth your while.

I wanted to share it then, but there were some procedures that still needed to take place. Without getting into any specific-details, I can now say that I have accepted a full-time position as a Technical Writer for the U.S. Marshals. I could not be more excited about this career move and I ask that you be patient in the coming weeks as I adjust to this new job. I think it’s fair to say that I will not be blogging as frequently in the coming weeks, but I promise to make my posts worth your while.

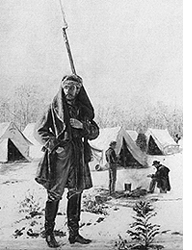

Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads

Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads

by Michael Aubrecht

Review inquiries welcome

Ordering information

Camp life is becoming very monotonous at our present abode. Winter is near at hand, and our tents a very inadequate shelter for this cold clime. Wood too has become an object-far off and bad roads to haul it over. The cold winds, howling around us like evil spirits, admonish us to prepare for "worse coming." -James J. Kirkpatrick, 16th MS Infantry, CSA

Often referred to as the "Crossroads of the Civil War," Spotsylvania County in central Virginia bore witness to some of the most intense fighting during the War Between the States. The nearby city of Fredericksburg and neighboring counties of Stafford, Orange and Caroline also hosted a myriad of historically significant events during America's "Great Divide."

Four major engagements took place in this region, including the Battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Spotsylvania Court House and the Wilderness. Today, the hallowed grounds that make up the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park are the second largest of their kind in the country. In addition, the area remains home to many historic Civil War landmarks, including Chatham, Salem Church, the "Stonewall" Jackson Shrine and Ellwood Manor. Dozens of monuments and roadside markers dot the landscape, and more than 200,000 tourists visit the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania region each year.

Similarly, from 1861 to 1865, hundreds of thousands of troops from both sides of the conflict marched through, fought at and camped in the woods and fields of Spotsylvania County and the surrounding area. The National Park Service christened the region "the Bloodiest Landscape in North America," stating that over a four-year period more than eighty-five thousand men were wounded and over fifteen thousand were killed. A number of exceptionally significant events also took place in the vicinity, including the first clash between Union general Ulysses S. Grant and Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee, as well as the first recorded skirmish between the Southern forces and U.S. Colored Troops.

This book focuses specifically on the Confederate encampments that spread across Spotsylvania County and the adjoining regions during the course of the Civil War. By using the testimonies of witnesses and words taken directly from published memoirs, diary entries and letters home, readers will be able to gain some insight regarding the day-to-day experiences of camp life for the Southern armies on campaign in the Old Dominion.

According to Spotsylvania County's official history, as presented by the tourism bureau:

Spotsylvania's roots extend back to 1721, when the colony of Virginia created a vast new county that stretched past the Blue Ridge Mountains. The county was named for Alexander Spotswood, lieutenant governor of the colony from 1710 to 1720. The City of Fredericksburg was formed from the county in 1728. Spotsylvania's many historic places include the following sites: a skirmish near the Rappahannock River between American Indians and a group led by Capt. John Smith; the first commercially successful ironworks in North America; a slave revolt attempted in the 1810s; and one of the nation's most productive pre-1849 gold mines. The county is probably best-known for the battles fought on its soil during the Civil War. Because of Spotsylvania's strategic location between the Confederate and Union armies, several major battles were fought in the county, including ones at Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, Fredericksburg, and Spotsylvania Court House, one of the bloodiest battles of the war. More than 100,000 troops from both sides died in Spotsylvania.

The nearby town of Fredericksburg blends almost seamlessly into the county's landscape. Its authorized biography states:

The City of Fredericksburg was established by an act of the Virginia General Assembly in 1728, on land originally patented by John Buckner and Thomas Royston of Essex County in 1681. It was named for Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-51), eldest son of King George II of Great Britain and father of King George III. Its older streets still bear the names of members of the British royal family. Located at the falls of the Rappahannock River, Fredericksburg flourished as a regional marketplace and prosperous seaport before the American Revolution. Although the Fredericksburg region is steeped in over 300 years of history, it is the area's part in the Civil War that attracts most of the visitors today. The City of Fredericksburg is strategically located midway between Washington D. C. and Richmond, Virginia. The City of Fredericksburg was a major objective for both sides during the Civil War. The city changed hands at least seven times and is the site of some of the most intense and crucial battles of the war.

Both locations, in addition to the surrounding counties of Stafford, Orange, Caroline and others, acted as major campsites and stationing locations for thousands of troops from both the Federal and Confederate armies.

Topics in this book include the construction and configuration of winter quarters, daily troop activities, church services, drills and assignments, foraging and supply acquisition, games and entertainment, crimes and punishment, servants, slaves and civilian aid, as well as personal reminiscences of missions and engagements. In addition, an intimate look into the family lives of several soldiers is revealed through their personal correspondence with loved ones who were left behind on the homefront.

Camp life for the common soldier during the Civil War was a mixture of a blessing and a curse. Off the battlefield, these encampments afforded a temporary sense of safety and security. They were also a bastion of boredom, and troops passed the time playing chess, singing songs and participating in a relatively new recreational activity called "baseball." At the same time, many soldiers fell victim to the indulgences of army life that included gambling, thievery, intoxication and prostitution. Thousands of men died of disease and dysentery from poor living conditions, and the scarring that was left behind on the land from camping armies proved to be just as destructive as the battles themselves.

Most soldiers in the field, regardless of their virtue, wrote constantly to reassure their friends and family, or simply to stay abreast of what was going on in their absence. As a result, there is a tremendous quantity of recorded memories available on life (and death) in these canvas communities. Enlisting with visions of glory, many of these men never expected to be away from their families for a long period of time, and few could have predicted the hardships that they would experience. Confederate forces suffered significantly more as the war dragged on, due to a rapidly depleting supply of military resources and basic life-sustaining necessities.

The broad demographic of these secessionists crossed all lines of society, which included everyone from privileged slave owners to poor farm boys. From a frustrated infantryman who described the monotony of his days like this: "The first thing in the morning is drill. Then drill a little more. Then drill, and lastly drill," to Confederate general Braxton Bragg, who commented on the debauchery of vices when he said, "We have lost more valuable lives at the hands of whiskey sellers than by the balls of our enemies," they all served in the same army and tented together regardless of their station.

Fortunately, we still have the written recordings of these soldiers who unknowingly preserved their own legacies by hand. Some pieces in this book were obviously penned early on as they bragged proudly about serving the "Cause." Others were composed long after they had become disenchanted with the war. Many of them were bittersweet as they captured the last chronicles of homesick husbands and fathers who later fell on the battlefield.

Due to inconsistent record keeping and the fact that most of the official records for the Confederate States of America were destroyed during the fall of Richmond in 1865, there is no definitive number that accurately represents the strength of the Southern army. Troop estimates range from 500,000 to 2,000,000 men who were involved at any time during the war. Reports from the War Department began at the end of 1861, indicating 326,768 men; in 1862 with 449,439 men; in 1863 with 464,646 men; in 1864 with 400,787 men; and the last report indicated 358,692 men. An estimate of enlistment throughout the war was 1,227,890 to 1,406,180.

Confederate general Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia is estimated to have had about 75,000 troops in its ranks during the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville and about 62,000 during the Overland Campaign, which included engagements at Spotsylvania Court House and the Wilderness. Therefore, one could estimate roughly that anywhere between 62,000 and 75,000 soldiers were stationed or encamped around the region from 1861 to 1865. These numbers pale in comparison when measured against the 135,000 Federal troops that were said to be stationed and/or camped in the neighboring Stafford County.

The exact locations of many of these Confederate camps remain unknown, but the winter quarters for the South's more senior commanders are recorded and marked prominently. These include the headquarters of General Lee, General Longstreet and General Stuart. Other locations of campsites include the grounds of the Spotsylvania Court House and along the Lee's Hill area near Massaponax. For many soldiers, who simply opened their letters with "camped near Fredericksburg," the meaning of "near" could mean anywhere in the Spotsylvania Court House or the surrounding region.

Many of the excerpts in this book were taken from the bound volumes collection at the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park Service archives. Some are quoted from the original Southern Historical Society Papers. Other pieces cite quotes found in the postwar autobiographies of those who survived. They have been credited in all instances, and the original wording has not been corrected or modified in any way, in order to preserve the integrity of the original documents.

Readers will likely note a distinct difference between the writing and spelling of those individuals who were schooled and those who were uneducated. Many of these transcripts contain poor grammar, no punctuation, atrocious spelling and primitive composition. They also contain an honesty and sincerity that could only be presented through mirroring their original structure. All of them provide an intimate look into the lives of those stationed at Confederate encampments in and around Spotsylvania County.

Judge J.W. Stevens, a member of Hood's Texas Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, recalled the average Confederate soldier's camp experiences in his recollections titled Reminiscences of the Civil War...(transcript follows).

[END PREVIEW]