Introduction excerpt

Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads

Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads

by Michael Aubrecht

Review inquiries welcome

Ordering information

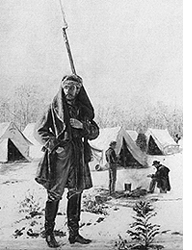

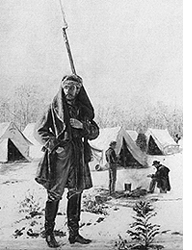

Camp life is becoming very monotonous at our present abode. Winter is near at hand, and our tents a very inadequate shelter for this cold clime. Wood too has become an object-far off and bad roads to haul it over. The cold winds, howling around us like evil spirits, admonish us to prepare for "worse coming." -James J. Kirkpatrick, 16th MS Infantry, CSA

Often referred to as the "Crossroads of the Civil War," Spotsylvania County in central Virginia bore witness to some of the most intense fighting during the War Between the States. The nearby city of Fredericksburg and neighboring counties of Stafford, Orange and Caroline also hosted a myriad of historically significant events during America's "Great Divide."

Four major engagements took place in this region, including the Battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Spotsylvania Court House and the Wilderness. Today, the hallowed grounds that make up the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park are the second largest of their kind in the country. In addition, the area remains home to many historic Civil War landmarks, including Chatham, Salem Church, the "Stonewall" Jackson Shrine and Ellwood Manor. Dozens of monuments and roadside markers dot the landscape, and more than 200,000 tourists visit the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania region each year.

Similarly, from 1861 to 1865, hundreds of thousands of troops from both sides of the conflict marched through, fought at and camped in the woods and fields of Spotsylvania County and the surrounding area. The National Park Service christened the region "the Bloodiest Landscape in North America," stating that over a four-year period more than eighty-five thousand men were wounded and over fifteen thousand were killed. A number of exceptionally significant events also took place in the vicinity, including the first clash between Union general Ulysses S. Grant and Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee, as well as the first recorded skirmish between the Southern forces and U.S. Colored Troops.

This book focuses specifically on the Confederate encampments that spread across Spotsylvania County and the adjoining regions during the course of the Civil War. By using the testimonies of witnesses and words taken directly from published memoirs, diary entries and letters home, readers will be able to gain some insight regarding the day-to-day experiences of camp life for the Southern armies on campaign in the Old Dominion.

According to Spotsylvania County's official history, as presented by the tourism bureau:

Spotsylvania's roots extend back to 1721, when the colony of Virginia created a vast new county that stretched past the Blue Ridge Mountains. The county was named for Alexander Spotswood, lieutenant governor of the colony from 1710 to 1720. The City of Fredericksburg was formed from the county in 1728. Spotsylvania's many historic places include the following sites: a skirmish near the Rappahannock River between American Indians and a group led by Capt. John Smith; the first commercially successful ironworks in North America; a slave revolt attempted in the 1810s; and one of the nation's most productive pre-1849 gold mines. The county is probably best-known for the battles fought on its soil during the Civil War. Because of Spotsylvania's strategic location between the Confederate and Union armies, several major battles were fought in the county, including ones at Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, Fredericksburg, and Spotsylvania Court House, one of the bloodiest battles of the war. More than 100,000 troops from both sides died in Spotsylvania.

The nearby town of Fredericksburg blends almost seamlessly into the county's landscape. Its authorized biography states:

The City of Fredericksburg was established by an act of the Virginia General Assembly in 1728, on land originally patented by John Buckner and Thomas Royston of Essex County in 1681. It was named for Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-51), eldest son of King George II of Great Britain and father of King George III. Its older streets still bear the names of members of the British royal family. Located at the falls of the Rappahannock River, Fredericksburg flourished as a regional marketplace and prosperous seaport before the American Revolution. Although the Fredericksburg region is steeped in over 300 years of history, it is the area's part in the Civil War that attracts most of the visitors today. The City of Fredericksburg is strategically located midway between Washington D. C. and Richmond, Virginia. The City of Fredericksburg was a major objective for both sides during the Civil War. The city changed hands at least seven times and is the site of some of the most intense and crucial battles of the war.

Both locations, in addition to the surrounding counties of Stafford, Orange, Caroline and others, acted as major campsites and stationing locations for thousands of troops from both the Federal and Confederate armies.

Topics in this book include the construction and configuration of winter quarters, daily troop activities, church services, drills and assignments, foraging and supply acquisition, games and entertainment, crimes and punishment, servants, slaves and civilian aid, as well as personal reminiscences of missions and engagements. In addition, an intimate look into the family lives of several soldiers is revealed through their personal correspondence with loved ones who were left behind on the homefront.

Camp life for the common soldier during the Civil War was a mixture of a blessing and a curse. Off the battlefield, these encampments afforded a temporary sense of safety and security. They were also a bastion of boredom, and troops passed the time playing chess, singing songs and participating in a relatively new recreational activity called "baseball." At the same time, many soldiers fell victim to the indulgences of army life that included gambling, thievery, intoxication and prostitution. Thousands of men died of disease and dysentery from poor living conditions, and the scarring that was left behind on the land from camping armies proved to be just as destructive as the battles themselves.

Most soldiers in the field, regardless of their virtue, wrote constantly to reassure their friends and family, or simply to stay abreast of what was going on in their absence. As a result, there is a tremendous quantity of recorded memories available on life (and death) in these canvas communities. Enlisting with visions of glory, many of these men never expected to be away from their families for a long period of time, and few could have predicted the hardships that they would experience. Confederate forces suffered significantly more as the war dragged on, due to a rapidly depleting supply of military resources and basic life-sustaining necessities.

The broad demographic of these secessionists crossed all lines of society, which included everyone from privileged slave owners to poor farm boys. From a frustrated infantryman who described the monotony of his days like this: "The first thing in the morning is drill. Then drill a little more. Then drill, and lastly drill," to Confederate general Braxton Bragg, who commented on the debauchery of vices when he said, "We have lost more valuable lives at the hands of whiskey sellers than by the balls of our enemies," they all served in the same army and tented together regardless of their station.

Fortunately, we still have the written recordings of these soldiers who unknowingly preserved their own legacies by hand. Some pieces in this book were obviously penned early on as they bragged proudly about serving the "Cause." Others were composed long after they had become disenchanted with the war. Many of them were bittersweet as they captured the last chronicles of homesick husbands and fathers who later fell on the battlefield.

Due to inconsistent record keeping and the fact that most of the official records for the Confederate States of America were destroyed during the fall of Richmond in 1865, there is no definitive number that accurately represents the strength of the Southern army. Troop estimates range from 500,000 to 2,000,000 men who were involved at any time during the war. Reports from the War Department began at the end of 1861, indicating 326,768 men; in 1862 with 449,439 men; in 1863 with 464,646 men; in 1864 with 400,787 men; and the last report indicated 358,692 men. An estimate of enlistment throughout the war was 1,227,890 to 1,406,180.

Confederate general Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia is estimated to have had about 75,000 troops in its ranks during the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville and about 62,000 during the Overland Campaign, which included engagements at Spotsylvania Court House and the Wilderness. Therefore, one could estimate roughly that anywhere between 62,000 and 75,000 soldiers were stationed or encamped around the region from 1861 to 1865. These numbers pale in comparison when measured against the 135,000 Federal troops that were said to be stationed and/or camped in the neighboring Stafford County.

The exact locations of many of these Confederate camps remain unknown, but the winter quarters for the South's more senior commanders are recorded and marked prominently. These include the headquarters of General Lee, General Longstreet and General Stuart. Other locations of campsites include the grounds of the Spotsylvania Court House and along the Lee's Hill area near Massaponax. For many soldiers, who simply opened their letters with "camped near Fredericksburg," the meaning of "near" could mean anywhere in the Spotsylvania Court House or the surrounding region.

Many of the excerpts in this book were taken from the bound volumes collection at the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park Service archives. Some are quoted from the original Southern Historical Society Papers. Other pieces cite quotes found in the postwar autobiographies of those who survived. They have been credited in all instances, and the original wording has not been corrected or modified in any way, in order to preserve the integrity of the original documents.

Readers will likely note a distinct difference between the writing and spelling of those individuals who were schooled and those who were uneducated. Many of these transcripts contain poor grammar, no punctuation, atrocious spelling and primitive composition. They also contain an honesty and sincerity that could only be presented through mirroring their original structure. All of them provide an intimate look into the lives of those stationed at Confederate encampments in and around Spotsylvania County.

Judge J.W. Stevens, a member of Hood's Texas Brigade in the Army of Northern Virginia, recalled the average Confederate soldier's camp experiences in his recollections titled Reminiscences of the Civil War...(transcript follows).

[END PREVIEW]

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 10:35 PM EDT

Updated: Wednesday, 7 October 2009 11:57 PM EDT

Permalink |

Share This Post

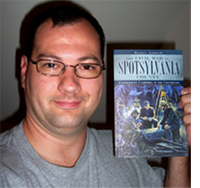

Hot off the press

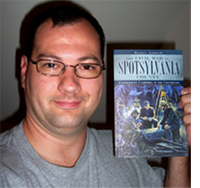

The author’s copies of my new book The Civil War in Spotsylvania County: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads arrived today. This 160-page title is my fifth published overall, and my second release with The History Press. I must say that I am very proud of the finished product. I will be setting up some signings and lectures in the future. Check back for bookings. In the meantime you can order at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, or direct from THP’s website.

The author’s copies of my new book The Civil War in Spotsylvania County: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads arrived today. This 160-page title is my fifth published overall, and my second release with The History Press. I must say that I am very proud of the finished product. I will be setting up some signings and lectures in the future. Check back for bookings. In the meantime you can order at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, or direct from THP’s website.

Here’s the teaser: From 1861 to 1865, hundreds of thousands of troops from both sides of the Civil War marched through, battled and camped in the woods and fields of Spotsylvania County, earning it the nickname 'Crossroads of the Civil War.' When not engaged with the enemy or drilling, a different kind of battle occupied soldiers boredom, hunger, disease, homesickness, harsh winters and spirits both broken and swigged. Focusing specifically on the local Confederate encampments, renowned author and historian Michael Aubrecht draws from published memoirs, diaries, letters and testimonials from those who were there to give a fascinating new look into the day-to-day experiences of camp life in the Confederate army. So huddle around the fire and discover the days when the only meal was a scrap of hardtack, temptation was mighty and a new game they called 'baseball' passed the time when not playing poker or waging a snowball war on fellow compatriots.

Race and remembrance

This weekend I spent a wonderful, albeit exhausting day at the Virginia State Fair. As expected, this event drew thousands of visitors and was spread out over 300+ acres at the Meadow Event Park near Kings Dominion. There was a carnival midway with lots of games and rides, an agricultural and equestrian fair, and most importantly, tons of fried food. Of course we were there for the kids so the majority of the day was spent watching them ride all kinds of nausea-inducing attractions while eating artery-clogging delicacies.

This weekend I spent a wonderful, albeit exhausting day at the Virginia State Fair. As expected, this event drew thousands of visitors and was spread out over 300+ acres at the Meadow Event Park near Kings Dominion. There was a carnival midway with lots of games and rides, an agricultural and equestrian fair, and most importantly, tons of fried food. Of course we were there for the kids so the majority of the day was spent watching them ride all kinds of nausea-inducing attractions while eating artery-clogging delicacies.

The addition of seeing a 1,000+ lb. pumpkin, meeting Lady Luck from the VA Lottery, and cheering on a lumberjack competition made the 9-hour marathon very satisfying. (We also saw a "snake woman" in the Side-Show Attractions that blew my mind and may have permanently traumatized my youngest daughter. The things they can do with smoke and mirrors nowadays...at least I hope it was an illusion!)

I was very pleased to see both a large Civil War camp, as well as a strong presence represented by the Sons of Confederate Veterans in both the Heritage Village and Convention Center. Everywhere you looked people were wearing rebel flag stickers (including yours truly) supporting Confederate Heritage Month. The re-enactor's exhibits, artillery firings, and camp life demonstrations were excellent. There was however, no Federal representation on site, which I found to be a bit odd. I have never been to a CW event where only one-side was represented.

Additionally I saw large crowds gathered at the Confederate Camp, Indian Village, Virginia Dept. of Historical Resources and VA Game and Fish Wildlife Pavilions, but very few people near the African-American History Shelter. What I found most odd was that the crowd as a whole was very diverse, yet I saw very few African-Americans stop at the exhibit. As I was watching an American-Indian tribal dance demonstration, I was facing toward the shelter and observed dozens of people of all colors walking right past it in favor of other exhibits. I counted 4-6 people total enter the tent. Later as I wandered from site to site, I was one of only 2 people (at the time) to peek in at their exhibits. There were some great educational pieces on the African-American struggle in early Virginia.

Presentation was certainly not the problem as they had some wonderful exhibits and artwork. Volunteers were not absent either as people were standing by for questions. Location wasn't an issue as they were literally the first stop at the top of the hill as you entered the footpath towards the village. So why did they appear to have so few visitors? And why so few African-Americans?

As the Vice-Chairman of the National Civil War Life Foundation, I sit on a very diverse board, which has vehemently pledged itself to preserving and presenting the Civil War-era histories of ALL participants. We take this directive very seriously. As a result, race in regards to visitation has become an important part of our focus. Nowadays I find myself being more aware of it when I visit battlefields, museums and other history-related events.

Unfortunately, now that I am paying attention, I see very little diversity around me on tours. On a personal level, I have maybe a handful of white friends who show an interest in history, but as one who spends a great deal of time at places like the Fredericksburg Battlefield and Monticello, I see very few minorities there when I visit.

My friends at The Jefferson Project have also opened my eyes to the differences in the ways whites and blacks view and acknowledge history. Some have told me very candidly that in their opinion, younger African-Americans today don't have an active interest in their people's story. Recently, I had a local black historian tell me that kids just don't care about their roots like they used to. He added that their attention is focused on today's athletes and entertainers because they are far more exciting than civil rights leaders who they can't relate to. Older people, in his mind, don't seek out black history because the past can be painful.

Whatever this gap is, I witnessed it on Saturday, at least for the time I was there. Perhaps the problem is in the presentation (or lack thereof)? I know that Gettysburg and Mount Vernon for instance; have made an effort to diversify their programs.

I would love to hear from my readers of all colors (especially you curators or NPS folks) if they have experienced or observed similar situations. Is there a racial difference in the general public's pursuit of history and is there a quantifiable lack of interest among any ethic communities when compared to others? My query is not just in regards to Civil War history either; I am speaking in regards to all periods that are presented today. A future post will be provided compiling the responses.

What are your thoughts?

Agreeing to disagree

Lately I have noticed that there are a lot of debates going on, some heated at times, all across the CW blogoshpere. The topics igniting these exchanges range from historical interpretation, to political perspectives and blogging etiquette. What I find so interesting is that neither side ever changes the other's opinion. There is both a passion and stubbornness to the process and I find it both educational and entertaining.

Lately I have noticed that there are a lot of debates going on, some heated at times, all across the CW blogoshpere. The topics igniting these exchanges range from historical interpretation, to political perspectives and blogging etiquette. What I find so interesting is that neither side ever changes the other's opinion. There is both a passion and stubbornness to the process and I find it both educational and entertaining.

The reason I feel inclined to comment on this today is that beyond the blogosphere, America as a whole seems to be fully engaged in this type of behavior. The divide in our nation, whether political, cultural, racial, spiritual, economical or any other "al" is clearly on the rise. The recent elections and cut-throat partisanship that is going on in the government, coupled with biased media coverage has seemingly enraged citizens everywhere. Everyone has an opinion, or an argument to voice and cynicism is en vogue. In a way, the very freedom to fight with one another is what America is all about, yet at the same time the idea of a "united" states speaks to a sense of unity.

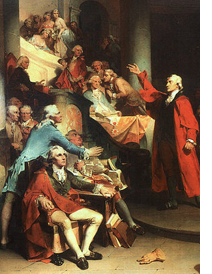

We all have the right to disagree, but I often wonder how far a society will fan the flames of dissent before any kind of compromise or agreement can be reached. It begs the question will the government ever be able to cross party lines and work together? Or will liberals and conservatives ever agree on anything? From the days of the Continental Congress to the syndication of the Glenn Beck show, America has always fought hard for its beliefs, especially at the podium.

It is, in essence, what we Americans do best, and the fact that we come from a lineage of instigators who stood up whether it be for independence, or secession, or civil rights, proves that the act of debate is one of the most precious freedoms that we possess. There was a time in our nation's not-so-distant history that men who came from the same land stood across from one another on a battlefield and killed each other. Be thankful that today, we can fire as many volleys as we want at each other across cyberspace because we live in a free society that encourages debate.

Just opened...

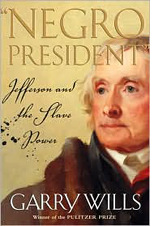

Today I started reading a book by Gary Wills titled "Negro President" Jefferson and the Slave Power. It has been sometime since I read a book for pure pleasure and I am REALLY looking forward to doing so. Unfortunately the newspaper that I periodically write book reviews for is undergoing budget cuts. (Those of you who were expecting reviews, I ask that you please remain patient as I have a great working relationship with the editor and will most likely be back in the future when their resources for freelancers are restored.) As a result, I am going to take some ME time and simply read for fun.

Today I started reading a book by Gary Wills titled "Negro President" Jefferson and the Slave Power. It has been sometime since I read a book for pure pleasure and I am REALLY looking forward to doing so. Unfortunately the newspaper that I periodically write book reviews for is undergoing budget cuts. (Those of you who were expecting reviews, I ask that you please remain patient as I have a great working relationship with the editor and will most likely be back in the future when their resources for freelancers are restored.) As a result, I am going to take some ME time and simply read for fun.

Last Christmas I snagged a hardback copy of this title at a used bookstore to add to my ever-growing collection of books on Thomas Jefferson. There is no other individual in our nation's history as brilliant or complex as TJ and I remain in awe of this man. Anyone familiar with my work with The Jefferson Project knows that I have a newfound fascination for examining the difficult issue of slavery and Jefferson - not only in regards to how Jefferson himself viewed race relations - but also how we today, as people of different colors reflect on his views.

According to Amazon, Wills' book is "a richly detailed study of the United States' tragic constitutional bargain with slavery, and meanders through the lives of several key figures in antebellum American history along the way." This includes issues surrounding the influence of slavery in the U.S. between 1790 and 1848.

In addition to Jefferson, fellow Founder John Quincy Adams and federalist/abolitionist Timothy Pickering also play major roles in this study. The underlying conflict here is a key component in the Civil War. That is the political struggle between Northern versus Slave-State powers which began at the time of Jefferson and erupted with the South's secession. Although I have no intention of working with this material in any formal capacity, I hope to gather some new insights to share with you here.

Beyond the subject matter, "Negro President" looks to be an enjoyable read. Gary Wills is a tremendous historical writer. He won a Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America, which describes the background and effect of Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863.

This past summer I read Joyce Appleby's Thomas Jefferson and I have been casually working my way through The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson: Autobiography and Public and Private Letters. It will be nice to read something that I can wrap my little brain around. I am also planning a trip back to Monticello in the fall to photograph the leaves and check out the new Visitor's Center. Perhaps this time I will have a different perspective as I walk Mulberry Row?

I will say that I am entertaining the notion of (someday - off in the future...) writing a lengthy piece on Jefferson's experiences here in Fredericksburg where, at an establishment known as "Weedon's Tavern," he met with his political contemporaries in 1777 and agreed to author a bill for religious liberties in America.

Today, the Religious Freedom Monument stands proudly as a testament to that event. Jefferson himself proclaimed this bill to be one of his three proudest achievements, alongside authoring the Declaration of Independence and founding the University of Virginia. In fact, these three accomplishments are the only ones that he deemed worthy enough to inscribe on his grave marker at Monticello.

BONUS: Gary Wills discussing this book on NPR’s Tavis Smiley Show LISTEN HERE

Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads

Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads

The author’s copies of my new book The Civil War in Spotsylvania County: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads arrived today. This 160-page title is my fifth published overall, and my second release with The History Press. I must say that I am very proud of the finished product. I will be setting up some signings and lectures in the future. Check back for bookings. In the meantime you can order at

The author’s copies of my new book The Civil War in Spotsylvania County: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads arrived today. This 160-page title is my fifth published overall, and my second release with The History Press. I must say that I am very proud of the finished product. I will be setting up some signings and lectures in the future. Check back for bookings. In the meantime you can order at  This weekend I spent a wonderful, albeit exhausting day at the

This weekend I spent a wonderful, albeit exhausting day at the  Lately I have noticed that there are a lot of debates going on, some heated at times, all across the CW blogoshpere. The topics igniting these exchanges range from historical interpretation, to political perspectives and blogging etiquette. What I find so interesting is that neither side ever changes the other's opinion. There is both a passion and stubbornness to the process and I find it both educational and entertaining.

Lately I have noticed that there are a lot of debates going on, some heated at times, all across the CW blogoshpere. The topics igniting these exchanges range from historical interpretation, to political perspectives and blogging etiquette. What I find so interesting is that neither side ever changes the other's opinion. There is both a passion and stubbornness to the process and I find it both educational and entertaining. Today I started reading a book by Gary Wills titled "Negro President" Jefferson and the Slave Power. It has been sometime since I read a book for pure pleasure and I am REALLY looking forward to doing so. Unfortunately the newspaper that I periodically write book reviews for is undergoing budget cuts. (Those of you who were expecting reviews, I ask that you please remain patient as I have a great working relationship with the editor and will most likely be back in the future when their resources for freelancers are restored.) As a result, I am going to take some ME time and simply read for fun.

Today I started reading a book by Gary Wills titled "Negro President" Jefferson and the Slave Power. It has been sometime since I read a book for pure pleasure and I am REALLY looking forward to doing so. Unfortunately the newspaper that I periodically write book reviews for is undergoing budget cuts. (Those of you who were expecting reviews, I ask that you please remain patient as I have a great working relationship with the editor and will most likely be back in the future when their resources for freelancers are restored.) As a result, I am going to take some ME time and simply read for fun.