Gene ruining another suit. (Mel Torme called this picture "a killer.")

A look at the king of percussion…and perspiration. By Michael Aubrecht, co-author of FUNdamentals of Drumming for Kids (w/ Rich Redmond)

In the dictionary of slang, the expression "by the sweat of his brow" is used to describe the route whereby an individual's hard work and diligence are rewarded. In a culture that was founded on the premise that one earns his keep, sweat, in American ideology, represents a physical manifestation of the price that one pays for expending exceptional effort while achieving success. Sweat therefore equates to an element of a performance worthy of our respect.

Naturally, one would assume that "sweat" is a suitable noun to be used when praising the efforts of an athlete on the playing field, but what about those of a musician on stage? Does the sweat resulting from the physical activity of playing music under the lights necessitate the same type of commendation as playing a sport? Obviously musicians perspire, but is that a notable measure when discussing their appeal as performers?

According to the legacy of one legendary musician, the answer is a resounding yes.

That musician is none other than the big band maestro Gene Krupa, who is considered by both drummers and non-drummers alike to be one of the greatest virtuoso performers ever to top the bandstand. Like myself, prior to penning this piece, most folks are probably unaware of the fact that sweat has played a prominent part in the legacy of "The Ace Drummer Man."

As a drummer, historian and Krupa devotee, I have spent many hours with my nose buried in yellowed newspaper articles, reading dusty eye-witness accounts and faded press packages that examined the impact of this amazing drummer, not just on music, but also on the popular culture of the 1930's and ‘40's. Surprisingly, the common description that keeps coming up again and again when reading about the life of Gene Krupa is "sweat."

In fact, from what I can interpret, perspiration appears to be more prevalent in Gene Krupa conversations than that of any other musician of his era. It is as if the raw physicality of Krupa's performance was, and is, just as revered as the musicality of it, and that is what makes the "sweat of Krupa's brow" particularly fascinating.

Back in the day, musicians of Krupa's caliber often published press manuals that were provided to potential promoters in advance of bookings. As predecessors to today's media kits, these instructional guides outlined everything from a musician's background and personal tastes, to their specific stage set-ups and equipment requirements. They also included a series of press-ready article templates that could be filled in and used for event promotion.

Gene Krupa's official MCA press manual from the late 1930's was titled "The Ace Drummer Man, Gene Krupa and his Orchestra: Publicity-Advertising-Exploitation." On page 12, there is a very peculiar template titled "Changes Clothes Often."

It states: Gene Krupa, drummer-bandleader, who is scheduled to appear at ____ on ____, through arrangements with Music Corporation of America, drums so strenuously that he needs an entire change of clothes at every performance. He carries a wardrobe of more than thirty suits which, although specially waterproofed, must be changed after each stage show or forty-five minute jam session. Despite the terrific pace Krupa's supply of energy is inexhaustible, for he never tires of his drums. At a recent theater appearance the maestro-drummer made thirty-five changes of clothes during the week, five changes a day.

This is the first time, in my research, that massive perspiration, necessitating multiple wardrobe changes, was used as a marketing tool for a jazz performer. Two other sections of the manual reinforce the apparent brutal toll of Krupa's drumming. The first piece, titled "Drummer vs. Athlete" correlates Krupa's musical performance to that of a sporting contest:

"When it comes to beating the drums, Gene Krupa, is generally considered to be the fastest man in the business, and according to health authorities, he expends as much energy in working as do athletes in pursuing strenuous sports." It adds that: "James Davies, health and exercise authority measured Krupa's exertion during a ‘jam session' and declared his drumming required as much energy as almost any other human motion. Davies compared the drumming with a five-minute handball game at top speed, a 14-foot pole vault, a six-foot high jump or a 24-foot broad jump. Two swing numbers in a row as Krupa plays them are more enervating than a mile run or four line plunges on a football field."

The next section in the narrative is titled "Loses Weight Nightly" and states: "Medical authorities have explained the phenomena of Gene Krupa, world's greatest drummer, who never tires during his workout, although he almost ends his nightly dance sessions in total collapse, by explaining that his physical system in now hardened to this serious strain - and is put back in shape by the five hearty meals which the drummer eats daily."

Looking at this analysis strictly in terms of swing-drumming, one can only imagine the physical exertion that speed-metal drummers of the modern era are expending over the course of a show. That in itself makes Krupa's skill set even more delicate as the style of music he perfected required much more diversity and finesse than that of a thrasher.

At the time of this publication though, there was no speed-metal. Popular music, more specifically swing music, wasn't gauged by the physical requirement of the arrangements. It was gauged by the intensity experienced by the audience while dancing to it. The taxing efforts put forth by the musicians performing it went relatively unnoticed - except when discussing Gene Krupa.

My point is that I've never read an article about Dave Lombardo that compares him to Olympic sprinter Usain Bolt; nor do I believe that Slayer's press kit specifically uses as a ticket teaser, the buckets of sweat that Lombardo produces while performing. The sweat that is most notably recalled at a Slayer concert is spent in the pit, by the crowd.

So what was it about the ferocity-induced sweat of a Gene Krupa performance that stood out so significantly that it became symbolic of his exceptional efforts? And why was this so unusual during his era?

No doubt anyone who witnessed Krupa laying down tribal beats on such hits as "Drum Boogie" and "Sing Sing Sing" would agree that his stamina was remarkable. In his book The World of Gene Krupa: That Legendary Drummin' Man, Bruce H. Klauber showcases the percussionist's epic perspiration as an example of the intensity of his playing. He writes, "Krupa made a visual impact, what with his...sweating...with hair flying and sticks twirling all the while under the light strobe."

In a 2003 Joe Levinson article titled Benny and Gene! Together Again! musician Dave Frishberg recalled how Krupa's energy didn't stop once he left the bandstand, even when he was soaked to the bone and obviously spent:

"Gene stood behind the bar and signed every damned picture," he writes, "He even signed special requests: ‘Can you write "To Sidney from Gene Krupa? Would you dedicate it ‘To Mary from Gene Krupa'? Make it to my granddaughter: ‘To Gwendolyn from Gene Krupa.' Gene was a real gentleman. He autographed every picture standing, sweating, tired, and holding back his anger."

The only conclusion that I can draw from all of this is that Krupa was the first, and more importantly, the best sweater on the bandstand - meaning that he performed at a level that eclipsed the efforts of his peers, as indicated by his sweat. In fact, Krupa sweated so much that it literally became his calling card.

This evidence inevitably proves that the energy expended when drumming can equal that expended in a sport. Gene Krupa was absolutely an athlete in terms of physical exertion, and he obviously excelled in his field. Most impressive is the fact that Krupa's physical flair did not overshadow, but ultimately accented his brilliant musicianship.

And that is what made Gene Krupa's sweat more significant and noteworthy than anyone outside of the music scene could probably comprehend. If respect can be measured by sweat, then it's fair to say that Gene Krupa sweated...a lot. Best of all, he earned every drop of that sweat, every time he sat behind the drum kit.

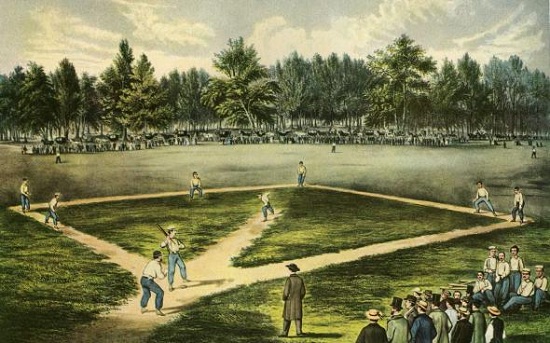

It’s been a little while since I posted anything Civil War or Baseball-history related and here’s a great opportunity to do both. A few weeks ago I received a very interesting email from Thomas Howland DeWitt. Thomas' great-great-grandfather Thomas Smith Howland was a member of the 33rd Massachusetts infantry. During the war Thomas wrote several letters home to his family that discussed the game of baseball being played in camp. Below is the transcript of one of them.

Camp 33rd Mass. Vols.

April 13th 1864

Dear Mother

I received my letter and papers yesterday. I’m sorry you have such bad luck with your hens; probably they will do better when warm weather comes. I hope you will enjoy your North Easter. We are having splendid weather. So warm that I sit in my shirt sleeves writing. The woods begin to look very green. Apple trees have been in bloom some time, and wild flowers are more plenty than I sever saw them at home in any season of the year.

The match game of the baseball between the staff and orderlies of Gen Hooker and thirteen players from our regiment came off this forenoon. The result was in favor of our regiment. The innings stood seventy to eleven. Pretty badly beat wasn’t they. They will play another game this afternoon. General Hooker ordered Colonel Wood to postpone brigade drill that they might play.

Locke, Cushman, and myself went over the mountain to the Tennessee fishing Saturday. In the gap through the mountains there are many beautiful wild flowers; I noticed several kinds of fern also. Tomorrow I will get some and send you. Snakes are getting to be very plenty along the river. The citizens say there are rattlesnakes here but I haven’t come across any yet. Going to have to hunt for them some day. We found an old boat in the river, bailed it out, and embarked. The fishing was rather poor. It had been raining and the water was muddy. WE caught a few catfish and some others that I didn’t know the of. Ducks were very plenty if we had brought our guns we could have done better shooting than fishing. We had a grand time. I felt independent once more, floating about on the river, seemingly hemmed in by the wild mountains. You cannot imagine what a pleasure it is to anyone who has long been under restraint; compelled to obey the least wish of his superiors to get away from their influence and feel that he is free to do his own will. I no not see how any man can be a slave. I like to be my own master. Well to chose even the profession of a soldier. I am willing and intend to remain in the army until I see the end of the rebellion, then I shall get out as soon as possible. But to return to fishing. We kept on down the river until we came to Kelly’s Ferry, the placed where our rations were formerly landed, and took the old corduroy road over the mountains to camp. A distance of some five miles. You have heard poets talk of the air laden with the perfume of roses but words fail me to describe the very odorous but not very delicious essence of mule that perfumed that old corduroy. It was almost insupportable. That portion of the road running over the mountain is ornamented with a dead mule every rod or two. Some are thinly covered with earth but many of them are entirely uncovered.

The second game of ball has come off and we stand seventy to seventeen almost as bad as before. Considerable money changed hands on the results of these two games. The fellows from Hookers are poor players. I don’t believe you could pick out thirteen men in our regiment but what could beat them.

Your affectionate son,

TSH

For more on Civil War baseball read my article for Civil War Historian magazine Battlefield Baseball and don’t forget to check out our You Stink! blog. Eric and I have begun working on our follow-up Baseball’s Could Have Beens and are starting to book our first speaking engagements of 2013. Stay tuned!

As I have been completely immersed in finalizing a highly anticipated book on drumming with my friend and co-author Rich Redmond, while simultaneously rediscovering my own swing chops, my mind is totally occupied with nothing else…

In the chronicles of drumming history, no two names resonate with more respect than those of Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich. These two musicians literally redefined their instrument and have inspired generations of drummers who still look upon them with a sense of wonder and worship. During their era, big-bands ruled the airways belting out swing, jazz and bebop numbers. At the time, it was the drummer who towered above all other soloists on the bandstand. Krupa and Rich were at the top of the heap, performing magnificent as individuals and divinely when brought together to “battle” one another.

It was during these “drum battles” that one could clearly see the dazzling similarities and differences in the playing styles of the participants. Krupa, clearly a dancer’s drummer, furiously worked the toms, creating a tribal backbeat that was accented with a brilliant use of the splash and cowbell. Rich, a tremendously technical player, played ridiculous rudiments at a speed that was virtually incalculable and incorporated stick tricks that left his peers shaking their heads in disbelief. To watch Krupa and Rich go at it must have been like watching Babe Ruth pitch to himself.

Unfortunately there are only a few of these epic engagements that have been captured either on audio or film. “The Original Drum Battle,” as it came to be known, took place at the kick-off of what was the 12th National Tour of Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic. That show took place at Carnegie Hall on September 13, 1952 and has become one of the most revered live recordings ever captured. Purchase on Amazon There are also two meetings of Gene and Buddy on film, both from television shows broadcast in 1966 and 1971.

On November 1, 1956, both drummers went into the studio with a group of JATP All-Stars, recording an LP called “Krupa and Rich.” Strangely, Gene and Buddy only play together on one tune, with the rest of the tracks featuring one drummer or the other. Although there is no recorded documentation, there is evidence that Buddy and Gene continued their drum battles from time-to-time through 1957. In a 1956 radio interview with the Voice of America's Willis J. Conover, the two drummers spoke of how they felt about the battles, as well as an upcoming JATP show where they were both set to appear. When asked about setting up these challenges, Rich explained the intentional spontaneity of them:

“…they never will be because then it would get kind of stiff, boring kind of thing. I think we get up on the stand every night and we look at each other and you listen to all the comments that come at you from the audience. Naturally, they're partisan groups and they're all shouting for their favorites, and we sit down at the drums and we laugh, and some nights Gene'll start a tempo or other nights I'll start the tempo. And we just start to play. And some nights it's great, and other nights it's laughs, and other nights it's boring, because that's what makes-anything that's spontaneous is a-it's a free feeling. We get up there and play just exactly what we feel like that particular night. When we play places like Carnegie Hall where the places are sold out we know that the people are listening uh, we play good. We play other places where we don't think there's too much interest-rather than listening-I think that people would rather be heard themselves-so we let them scream and we play under them.”

In 1966 Sammy Davis Jr. played host to the mighty two on a broadcast of his ABC television program:

The last, on-camera meeting between Krupa and Rich that we know of took place on October 12, 1971. The occasion was a Canadian television special hosted by their friend and fellow percussionist Lionel Hampton. Rich came out at the very end of the program to participate in a four-way drum duel featuring Hampton, Krupa, Rich and Mel Torme'. After Krupa passed away in 1973, Rich continued to battle other drummers off-and-on until his own death in 1987.

Today, over five decades since Krupa and Rich first took the stage to duel, musicians and music lovers alike are still amazed and invigorated by these incredible performances that have not been duplicated or witnessed since.