Last post on this matter

Chaplain Jacob Duché leading the first prayer in the First Continental Congress at Carpenter's Hall, Philadelphia, September 1774: mezzotint, 1848.- Granger Collection - artist unknown

The Christian Nation “debate” is not really an intellectual contest between legitimate contending viewpoints. Instead, it is a manufactured “controversy” akin to the global warming “debate.” On the one side are purveyors of a rich and complex view of the past, including most historians who have written and debated fiercely about the founding era. On the “other side” is a group of ideological entrepreneurs who have created an alternate intellectual universe based on a historical fundamentalism. In their drive to create a usable past, they show little respect for the past as a foreign country. - Paul Harvey, blogger at Religion in American History and history professor at the University of Colorado.

The debate over America being a Christian Nation has become a recurring topic here at “Blog, or Die.” Over the last few days I have remained frustrated while searching for a way to intelligently explain this dispute and offer some kind of closure. My conclusion is that the argument is fruitless. Neither side will ever concede. The belief or disbelief in a Christian Nation is far too personal. It involves the pairing of two sacred subjects: religion and politics. It was this sense of futility that led me to seek out other bloggers who are dealing with the same dilemma. Not surprising, the more objective and logical explanations were found in the academic realm. This is where John Fea’s blog led me to Paul Harvey’s blog.

After reading Professor Harvey’s remarks (above) I was immediately struck by his use of the term “foreign county” when referring to our nation’s past. Perhaps the biggest problem with the Christian-nationalist’s perspective is that they tend to treat the Founding Fathers as if they were our contemporaries. They want to believe that the Founders thought like we think and valued what we value. The reality is that they were not the same as us. They lived in a different time - in a different world. Anyone who studies history recognizes the natural progression of human culture. People of the past are not always motivated by the same issues and concerns that motive today’s society. In that sense Colonial America and the early Republic were “foreign countries.” It seems silly to me that anyone would try to sustain a modern perspective by drawing a parallel between themselves and someone who lived 250 years ago.

The trouble with today’s debate isn’t the practice of presentism. It is, according to Harvey, “the selective use of anecdotes, proof texts, and the decontextualized way of doing history.” I have blogged about the conundrum of using convenient quotes before. Find any verse from Jefferson or Adams that supports organized religion and I’ll find two or more that contradict it. It has been my experience that most proponents of the Christian Nation work in reverse. Instead of entering the argument with no preconceived notions - allowing the unraveling of facts to determine a conclusion, they begin their search in defense of their conclusion - going backwards until they find something that validates their beliefs. My supervisor would call that "ass-backwards."

On his blog Harvey adds that this approach is used in order to legitimize the anti-Statist, Christian-nationalist, Evangelical-victimization argument in the present. He writes, “The issue, then, is not Christian conservatives advocating their views in the public square. The problem, rather, is their claim that their beliefs and readings of documents from the past represent a kind of legitimate scholarship that should have its place in the public ‘debate.’” It is the battle between history and theology that ultimately leads nowhere. In other words, the argument over America being a Christian Nation is a case of apples versus oranges. One side is searching for facts, while the other is seeking validation.

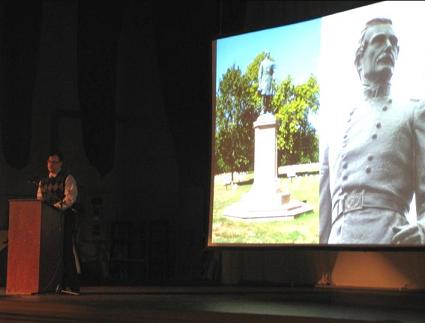

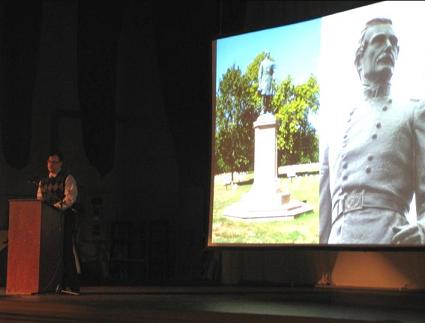

123rd PA Vols lecture

As promised, here are the transcripts from my lecture on the “Gallant Boys of the 123rd” for the 6th Annual Civil War Weekend at the Carnegie-Carnegie Library and Music Hall in Pittsburgh. (I hope to post a video of this talk in the near future.)

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. Before I begin I would like to thank Maggie Forbes, Diane Klinefelter, and the rest of the good folks here at the Carnegie-Carnegie for their wonderful hospitality. I would also like to thank each and every one of you for coming today. Civil War Weekend has become quite an event and it is an honor for me to be here. Back in November, I had the privilege of hosting a premiere for a documentary on Richard Kirkland titled “The Angel of Marye’s Heights.” The response I received was outstanding, so I was absolutely thrilled when Maggie and Diane asked if I would return. Today I am going present some insights on the “Gallant Boys of the 123rd” – the Pennsylvania Volunteers. This will be followed by an exclusive screening of our half-hour documentary and a short Q&A session will follow that.

Both of these topics, the lecture and the film, relate not only to one another, but also directly to the Capt. Thomas Espy Post No. 153 of the Grand Army of the Republic right here at the Carnegie-Carnegie. If you stick around to watch the film later, the men depicted in our reenactments could have very likely been members of the 123rd. Today we are joined in the Music Hall by Pittsburgh author Scott Lang who wrote The Forgotten Charge: The 123rd Pennsylvania at Marye's Heights, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Scott is the REAL expert on the PA Vols. and he has been gracious enough to display his wonderful collection of 123rd relics. Be sure to check those out.

Down in Fredericksburg where I live there are four major Civil War Battlefields. These hallowed grounds include Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, Chancellorsville and The Wilderness. Atop the Fredericksburg Battlefield is a bluff known as Marye’s Heights. The legacy of this location is the focal part of our film, but for my talk we will begin by focusing on what stands there today.

Nowadays atop Marye’s Heights stands a striking monument that commands the center of the Fredericksburg National Cemetery, the final resting place of 15,000 Federal troops who never made it home. This statue portrays General Andrew A. Humphreys and commemorates his Division of Pennsylvania Infantry, the Fifth Corps. Humphrey’s men took place in the Federal Army’s assault at Marye’s Heights and made it to within 100 yards of the Confederate position on this ridge before being cut to pieces and driven back. Theirs was the furthest to advance on this portion of the Army of Northern Virginia’s lines during the Battle of Fredericksburg. On the monument's pedestal read the names of the units that participated in this doomed assault with unparalleled courage and conviction. Included on this list is the 123rd Volunteer Regiment who were mustered out of this region. Many of these men had direct ties to this area either as residents or through family relations.

We know for a fact that there were at least three veterans of the 123rd who survived the war and were members of the Espy Post - right here at the Carnegie-Carnegie. They were: Dennis Gallagher, a member of Company F, who was born in Ireland. After the war he lived in Chartiers. James Harper, a member of Company G, who was born in Washington County and later, lived in McDonald, PA. And William Kirby, a member of Company C, who was born in Allegheny County and settled in Carnegie.

While preparing for this talk I came to the conclusion that there is a very limited amount of materials published specifically on the 123rd. Shortly after the war Samuel Bates wrote a study on the “History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-65” and of course our friend Scott wrote the other. Both of these books served as a valuable reference. That said it would be redundant for me to simply rehash Mr. Bates or Mr. Lang’s findings. I wanted to bring something special to the podium. What I was able to do, through the help of my friends at the National Park Service, was to get the complete transcripts of 4 diaries belonging to members of the 123rd. None of these memoirs have been published to my knowledge and each one is literally a porthole into the past.

Today I will be quoting directly from these diaries, as nothing quite captures the experience of these men more than their own words. Before I do that here is some quick background on the 123rd Volunteer Regiment: They were organized at Pittsburgh, Allegheny City, and Tarentum in August of 1862. They moved to Harrisburg, then to Washington, D.C., where they were attached to the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 5th Army Corps, in the Union’s Army of the Potomac. In 1862 they participated in the: Maryland Campaign (September), Duty at Sharpsburg, MD (October), Movement to Falmouth, VA (October –November) and the Battle of Fredericksburg, VA. (December 12-15). The 123rd would also participate in the infamous 1863 Mud March toward Spotsylvania, and the unsuccessful Chancellorsville Campaign before being mustered out on May 13th of that same year.

Their regimental losses during service were 3 Officers and 27 Enlisted men killed or mortally wounded - and 1 Officer and 41 Enlisted men dead by disease. Total loss over the course of their service was a mere 72 men. That is an amazing number when you look at the engagements that the 123rd participated in. To put that number in perspective: The approximate Union casualties at Antietam: over 12,000 killed or wounded. At Fredericksburg: again - over 12,000 killed or wounded. At Chancellorsville: 17,000 Union men killed or wounded. 72 losses is therefore extraordinary. I would have imagined it to be much-much higher. Perhaps that is a testament to their prowess as fighting men or maybe their luck.

For the purpose of this program let’s focus specifically on their service at Fredericksburg. On a cold winter’s day in December of 1862, Federal forces suffered terrible casualties in several futile assaults against Confederate defenders on the heights behind the city of Fredericksburg. This tremendously one-sided victory renewed the southern force’s resolve while stopping the Union Army’s march toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. The 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteers from Pittsburgh and the surrounding region was right in the thick of it proving that the Steel City’s contribution to the war effort went far beyond the mere production of arms and artillery.

National Park Historian Frank O-Reilly wrote a description of the 123rd’s preparation and entry into battle in his book “The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock.” He wrote: “The 123rd Pennsylvania and the 131st Pennsylvania were in front and the 155th Pennsylvania and the 133rd Pennsylvania behind them. Humphreys ordered his troops to rely on the bayonet and demanded that their weapons be emptied. He had the muskets “rung” (by dropping ramrods noisily into the barrel) to prove they were unloaded. Some of the regiments still carried their gear. …Mounted officers moved to the front. Men touched elbows and roared out of the ravine with a resounding yell.”

At first glance, it sounds like Humphreys is simply ordering his men forward into the fray with no regards for them, but he was actually one of those officers who charged alongside his troops. He once recalled that “For certain good reasons connected with the effect of what I did upon the spirit of the men - and from an invincible repugnance to ride anywhere else - I always rode at the head of my troops.”

Historian Larry Tagg wrote that Lt. Cavada of the general’s staff recalled Humphreys just before he took his troops on the field at Fredericksburg. He stated that: “Humphreys had bowed to his staff in his courtly way, “and in the blandest manner remarked, ‘Young gentlemen, I intend to lead this assault; I presume, of course, you will wish to ride with me?’” Since it was put like that, the staff had done so, and five of the seven officers were knocked off their horses. After his men had taken as much as they could stand in front of the Stone Wall on Marye’s Heights, the next brigade coming up the hill saw Humphreys sitting his horse all alone, looking out across the plain, bullets cutting the air all around him.” He adds, “Something about the way the general was taking it pleased them, and they sent up a cheer. Humphreys looked over, surprised, waved his cap to them with a grim smile, and then went riding off into the twilight. In this way Humphreys had turned his first division’s dislike of him into admiration for his heroic leadership.”

So although the boys of the 123rd were literally marching into a maelstrom of musket fire, they were following a commander who was called upon to be just as courageous as them. It’s really remarkable that he was not shot from his horse – although his horse would eventually be shot out from under him. A diarist from the 123rd who participated in this charge later recalled that as soon as they crested the ridge in front of the Confederate position, stepping into the range of Confederate rifles: “It was then that the balls came thick and fast.” Another stated that the Confederate guns created “such a din as I never wish to hear again.” Soldiers trampled wounded men and horses, and crossed shattered fences. The surroundings, according to one Keystone State volunteer, “were certainly enough to gratify and studios or morbid desire.”

Perhaps the best description comes courtesy of Samuel P. Bates who described it like this: “On the following day the battle opened, and at three P. M., after the corps of Hancock and French had been checked and terribly slaughtered, Humphreys' Division was ordered in. It was a forlorn hope, but gallantly it went forward, and charged again and again those impregnable heights. What brave men dare do, they did; but it was all in vain. No human power could stand against the storm that swept that fatal ground. The One Hundred and Twenty-third occupied a position in the line, with its right reaching nearly to the pike, and bore manfully its part in the battle, suffering grievously. Lieutenant James R. Coulter was among the killed, and Captain Daniel Boisol and Lieutenant George Dilworth among the mortally wounded. The entire loss was twenty-one killed, and one hundred and thirty-one wounded. All night long it lay in position, and through the weary hours of the following day, exposed to a constant fire of the enemy's pickets, and until nine at night, when it was ordered to retire.”

When the smoke cleared after that initial series of assaults, thousands of men has fallen on the field at Fredericksburg, and hundreds more were trapped on the field, unable to retreat or go forward. The area in front of the stone wall at the sunken road became a no-man’s land and sharpshooters continued to pick off survivors who were forced to hide behind the bodies of their dead comrades.

Alexander Altsman, an infantryman in Company E was wounded in the melee and in his diary he wrote of his unfortunate experience at Fredericksburg. On December 13th he writes: “We crossed over the River today the ball and shell were flying through the town, tearing through our ranks William Worthington was struck in the head with a solid shot, but was only stunned our division was put in the fight about sundown.” He continues: “I was the 5th one in our company that was wounded. The following is as correct a list of killed and wounded as I can ascertain: John R Munden - killed David Beatty, Albert Boyce, Chas McTiernan, Henry March, John Stevens, Christian Haber, Samuel Reynolds, William Smith and 1st Lieutenant George Dillworth - wounded. I made my way to the hospital and got my wound dressed but could not get the ball extracted as the doctor could not find it.”

On the 14th he writes: “Did not rest very well last night. Can hobble about a little. The house that we are in now has been very well furnished at one time.” The next day he says, “We were brought over the river this morning, but did not get out of the ambulance until evening.” This is two days after he was shot. Several weeks later – on January 29th, in Washington DC, at Harwood Hospital he finally gets proper medical attention. He writes, “The ball which I received at the Battle of Fredericksburg was extracted this morning. It is a minnie rifle ball and it is bruised a great deal.” So private Altsman is in the 123rd’s charge at Fredericksburg where he is wounded in combat and, over a month later, he is finally relieved of his bullet. In an age of so much death from blood loss and infection, it is amazing to me that he simply refers to the wound’s bruising, like it’s a nuisance.

A comrade in arms named Hugh Hall Stephenson wrote the following series in his diary: December 13th, Saturday: “We went into battle about 3 o’clock and fought till night. List 1 killed and four wounded in Company E. The firing was terrible. Worse than at Antietam.” (That statement is striking as Antietam witnessed bloodshed like no other battle. There 23,000 (yes I said thousand) casualties at that engagement. Over 2100 Confederates - and over 1500 Federal troops killed.) He continues: December 14, Sunday: “Lay on the field all night and all day today. There has been little firing going on all day. At night we were marched back to town and slept in the street.”

Of course in war, not all who are wounded survive the retreat to make it home. James M Watson was another Union soldier who was wounded in the 123rd’s failed assault. Like Altsman, he was hit, and like Stephenson, he was trapped on the field. In fact, Watson was wounded and remained bleeding on the field until the following morning. He would later be removed by an ambulance crew assigned to the 123rd, but would die six weeks later on January 28th, 1863, the day before Altsman had his surgery to remove that ball. So the suffering that these men endured went on long after the rifles and cannons had ceased firing. And that to me personifies the courage and conviction of the Civil War soldier.

In closing today I would like to quote a Union Colonel from the 2nd Brigade named Peter Allebach who sums up the experience of all Pennsylvania Volunteers at Fredericksburg. He writes: “The thought of momentary death rushed upon me and it required every exertion to hush the unbidden fear of my mind. Sulfurous smoke and flame stabbed at the dwindling attackers, leaving the field covered with dead and wounded. We could go no further as the carnage was too fearful.” To put that in perspective Rebel bullets shredded the colors of the 123rd, who later counted 12 large holes in its flag and another through the staff.

Despite facing certain death, the gallant boys of the 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment fulfilled their duty to their country and gave it their all in one of the most lop-sided engagements of the entire Civil War. It is therefore our obligation to see that their story and the stories of all participants in America’s “Great Divide” are preserved for future generations. The Capt. Thomas Espy Post No. 153 of the Grand Army of the Republic right here at the Carnegie-Carnegie does this each and every day and I for one am very thankful for their contributions to maintaining Civil War memory.

In honor of Mother's Day

Mary Ball Washington, The Mother of the Father of our Country

By Michael Aubrecht (Patriots of the American Revolution July/August 2010)

There is an old adage that goes “Behind every great man is a great woman.” Throughout the course of American history this maxim has proven true in the lives of remarkable ladies, whose legacies are equally as memorable as their male counterparts. Many of these female protagonists made their mark as the spouses of celebrated gentlemen, while others followed in the footsteps of their remarkable fathers. Some women simply gave birth to their sons and then raised them for greatness. This is perhaps the noblest feat of all. One woman who nurtured perhaps our nation’s greatest citizen, soldier, and politician was Mrs. Mary Ball Washington.

In Stafford County Virginia, on the bank of the Rappahannock River sits Ferry Farm, the childhood home of our country’s first president. A short distance away in the small town of Fredericksburg stands the Mary Washington House. Both of these sites host thousands of tourists each and every year, yet the woman who lived at them both for the longest time is often forgotten in favor of her offspring. This is understandable as her son is held in the highest of venerations of any historical figure, but the story of Mary Ball Washington is one of a remarkably independent lady.

Today this Virginia farm woman is remembered as a citizen of great virtue and tenacity. According to the memoirs of her friends and family she was truly beloved, and equally infuriating. She was a splendid wife who was prematurely widowed and a stubborn mother who struggled in her relationship with her children. She was also a practicing Christian, who was said to have spent a great deal of time in meditation, seeking guidance and finding strength in her own faith. Hers is a legacy of independence and fortitude, passed down from mother to child.

Mary Ball was born in Lancaster County Virginia in 1708 and was one of many siblings in a combined family. Her father was a gentleman named Joseph Ball and her mother was the widow Mary Johnson. The first Ball family home was located at Epping Forest where her grandfather, William Ball, had immigrated from England to the Old Dominion around the year 1650. Unfortunately, as it often happened in this period, Mary’s parents fell sick and prematurely succumbed to their maladies, leaving her fatherless at age three and motherless at age twelve or thirteen.

As an orphan Mary was placed, in accordance with the terms of her mother’s will, under the guardianship of Mr. George Eskridge, who was a local attorney and friend of the Ball family. For the next decade, she lived with the Eskridge family, along with her married half-sister Elizabeth Bonum. Although there are not many records on this part of her life, it is apparent that Mary was well cared for. She was educated, an avid reader and a skilled equestrian.

This quality of upbringing for an orphan during colonial times was a blessing indeed, as many children without parents or relatives ended up on the streets or in unloving homes. Often they were abused and considered a source of labor. Mary had been very fortunate to be placed in the care of an established lawyer who had a comfortable income and a way of nurturing her. Because of this, she was given the opportunity to grow into what was considered to be a well-bred young woman.

By 1731, Mary had reached the age of twenty-three, which was considered old-maid status by Colonial standards. Once again good fortune favored her as she met a strapping entrepreneur named Augustine Washington. Augustine’s family, much like Mary’s had been in the colonies since the mid-1600s. He too was educated and had been schooled in England. Augustine was a well-established widower, fourteen years her senior, with three children, Lawrence, Augustine, and Jane.

Obviously there are no photographs of Mary Ball Washington, but there are several documented impressions of her as a young lady. She was considered to be tall for a female and later said to resemble her eldest son. Her cousins found her to have a very kind expression and two surviving portraits depict her as a typical young maiden. Beauty however appears to be in the eye of the beholder as Lafayette is said to have likened her to a Roman matron, while Eleanor Parke Custis, the wife of Betty Lewis’ son Lawrence, described her as “remarkably plain in her dress.”

After a brief courtship, the practicality of their relationship led to matrimony between the twenty-three year-old Mary and her thirty-seven year-old suitor. Augustine filled the much-needed role of provider while Mary became a nurturer for his children. At the onset of their marriage, the Washington’s were not extravagantly wealthy, but they would grow in net worth as Augustine’s success grew at a regional level. The following February Mary gave birth to a son, the first of six children. They named him “George” after George Eskridge, Mary’s adopted father.

The Washington family lived on a beautiful plantation called Pope’s Creek, which was later called Wakefield. There they prospered and the family grew. In the end Mary and Augustine had six children altogether: George, Betty, Samuel, John Augustine, Charles, and Mildred. Remarkably, most of the entire Washington-Ball clan found success in their adult lives. Betty married Fielding Lewis and built the Kenmore Estate. Samuel served as a justice of the peace and a lawman in Stafford County. John Augustine founded the Mississippi Land Company. Charles helped to establish Charles Town in West Virginia. Mildred unfortunately died at the age of sixteen months.

The Washingtons moved to Hunting Creek in 1736, which was later christened Mount Vernon. In 1738 Augustine purchased a farm (which was later known as Ferry Farm) to be closer to his iron business. It was then that the family moved and settled in Fredericksburg. Here is where the tall tales that would become ingrained in Washington’s legacy originated; whether it was George confessing to chopping down a cherry tree, or skipping a silver dollar across the river. After settling at the new homestead in central Virginia, Mary kept busy with overseeing the day-to-day operations of the farm and tending to her children. Augustine focused his energies on his business interests.

In 1743 tragedy repeated itself in the life of Mary Ball Washington, as her husband passed away unexpectedly at the age of forty-nine. Mary, who had been orphaned in her early teens, was now widowed at the tender age of thirty-five, with five children. George was only eleven years old at the time of his father’s death. In accordance with Augustine’s will, Mt. Vernon was left to George’s half-brother Lawrence, and the 600-acre family farm in Fredericksburg was left to George. Provision was made for Mary to receive the benefit of the crops for five years and possession of the property until George came of age. Various portions of other land holdings and personal property were divided among the all of the siblings. This included slaves.

Although there were tumultuous years that followed, Mary was said to have remained a vigilant parent. Historians over the years have traced George’s epic honesty and fortitude to the influence of his parents and some have even credited his mother alone with his rise to greatness. According to the publication Archiving Early America:

“To Mary Ball Washington we owe the precepts and example that governed her son throughout his life. The moral and religious maxims found in her favorite manual — ‘Sir Matthew Hale’s Contemplations’ — made an indelible impression on George’s memory and on his heart, as she read them aloud to her children. That small volume, with his mother’s autograph inscribed, was among the cherished treasures of George Washington’s library as long as he lived. When George was 14 years old, his half-brother Lawrence obtained a midshipman’s warrant for him in the English naval service. George made plans to embark on-board a man-of-war, then in the Potomac. His baggage was already on the ship. But at the last minute his mother refused to give her consent, preventing her son from a life that would have cut him off from the great career he would eventually pursue. A noted biographer described her action as the debt owed by mankind to the mother of Washington.” (It was rumored that Mary gave George a beautiful pen-knife as a consolation gift, and playfully had it engraved “Always Obey your Superiors.”)

Mary remained in mourning and lived in Fredericksburg for more than forty-five years after the death of her husband. She never remarried, which could be viewed as a testament to her constitution and strong will. She was, by all accounts, a self-supportive woman, although she was obliged, once George came of age, to rely on his generosity for financial support. As George’s military and political career prospered, his mother continued to be a meager farmer who maintained the land that her husband had purchased.

Years passed and the relationship between Mary and George deteriorated. Although she was by no means poor, she regularly complained to outsiders that she was destitute and neglected by her children, much to George’s embarrassment. This led to an animosity between mother and son that persisted. Despite the strain on their relationship, George remained in contact with his mother and made it a point to send her correspondence while deployed on military affairs. One preserved letter, dated 1755, followed a military engagement early on in his career and was meant to reassure Mary of his safety. George concluded his letter with the phrase “Your most dutiful son.”

At the age of 64, Mary became too old to run the farm. In 1772, her eldest son purchased a home for her in downtown Fredericksburg, where she lived for the remaining seventeen years of her life. When the War for Independence began, General George Washington took command of the Continental Army in June of 1775 and did not see his mother again for nearly ten years. During this time Mary remained in town and rarely visited the family farm.

It was recorded that Mary’s stubbornness began to rear its ugly head. She requested that the Virginia House of Delegates (formally the House of Burgesses) provide her with an allowance, since she was, after all, the mother of the army’s supreme commander. She then petitioned for a state pension and also to have her taxes lowered. None of her requests were granted.

Despite their rift, Mary’s proudest moment may have come during a visit by her son to Fredericksburg in February of 1784. After being awarded the honors of the town, George accepted and responded with a declaration honoring “My reverend mother by whose maternal hand, early deprived of a father, I was led to manhood.”

George continued to pay Mary’s rent for the livestock and slaves at Ferry Farm and in 1787 he strongly urged her to move from the house and live with one of her children. It was thought that she might move in with her son John, however John died before she ever moved and she never agreed to go elsewhere.

Two years later, President-elect George Washington, en route to New York for his inauguration, paid his last visit to his mother at the house in Fredericksburg in April of 1789, four months before she died. It was reported that the two were reunited and repaired their relationship. George Washington Parke Custis, the president’s adopted son, gave a moving account of Mary Ball Washington’s last meeting with her son. He recalled:

“Immediately after the organization of the present Government, the Chief Magistrate [Washington] repaired to Fredericksburg to pay his humble duty to his mother, preparatory to his departure for New York. An affecting scene ensued. He told her I have come to bid you an affectionate farewell. So soon as the weight of public business which must necessarily attend the outset of a new Government can be disposed of, I shall hasten to Virginia, and— Here the matron interrupted with, “And you will see me nomore; my great age, and the disease which is fast approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world; I trust in God that I may be somewhat prepared for a better. But go, George, fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to have intended for you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and a mother’s blessing be with you always.”

He added, “The President was deeply affected. His head rested upon the shoulder of his parent, whose aged arm feebly, yet fondly, encircled his neck. That brow on which fame had wreathed the purest laurel virtue ever gave to created man relaxed from its lofty bearing. That look which could have awed a Roman Senate in its Fabrician day was bent in filial tenderness upon the time-worn features of the aged matron. He wept. A thousand recollections crowded upon his mind, as memory, retracing scenes long passed, carried him back to the maternal mansion and the days of youth, where he beheld that mother, whose care, education and discipline caused him to reach the topmost height of laudable ambition. Yet, how were his glories forgotten while he gazed upon her whom, wasted by time and malady, he should part with to meet no more! Her predictions were but too true. The disease which so long had preyed upon her frame, completed its triumph, and she expired at the age of eighty-five [actually eighty-one], rejoicing in the consciousness of a life well spent, and confiding in the belief of a blessed immortality.”

President Washington went on to serve his country once again, as Mary Ball Washington died at the age of eighty-one from cancer during his first year in office. She was buried at Kenmore on the Lewis plantation, a few steps from “Meditation Rock.” This location was her favorite retreat for reading, prayer and meditation. It somehow seemed fitting that a woman who was so connected to the area’s land, would be returned to it upon her death. The plaque at the base of the rocks reads: “Here Mary Ball Washington prayed for the safety of her son and country during the dark days of the revolution.”

Mary’s impact on the region remained and, in the 1830s, the women of Fredericksburg banded together to raise funds for a monument dedicated to her memory. The following year, the prominent Silas Burrows of New York offered to pay for it himself. In laying the cornerstone, Andrew Jackson said this about her:

“Mary Washington acquired and maintained a wonderful ascendancy over those around her. This true characteristic of genius attended her through life, and she conferred upon her son that power of self-command which was one of the remarkable traits of her character. She conducted herself through this life with virtue and prudence worthy of the mother of the greatest hero that ever adorned the annals of history.”

Unfortunately Mary’s first marker was destroyed during the Civil War, but another one was placed in 1893. It was formally dedicated by President Cleveland in May of 1894 and featured an inscription that paid tribute to what may be considered her greatest accomplishment. It simply reads “Mary the Mother of Washington.” Yet perhaps it was her beloved son George, who most fittingly summed up the life of Mary Ball Washington when he said, “My mother was the most beautiful woman I ever saw. All I am I owe to my mother. I attribute all my success in life to the moral, intellectual and physical education I received from her.”

Few women have reared children who rose to the heights of Mary Ball Washington’s son George. Her motherly influence on him was a cornerstone in the foundation of America’s greatest father and helped to make him the most celebrated military and political figure in our nation’s history.

Sources:

George Washington's Boyhood Home at Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore (www.kenmore.org, George Washington Foundation)

In Search of the ‘real’ Mary Ball Washington by Paula S. Felder (The Free Lance-Star, March 12, 2005)

Mary Ball Washington: “His Revered Mother” (History Library Point: Central Rappahannock Regional Library)

Mary and Martha, the mother and the wife of George Washington by John Lossing Benson (1886, Harper & Brothers, Franklin Square)

The Life of George Washington; with Curious Anecdotes by M. L. Weems (1877, J.P. Lippincott & Co. Philadelphia)

Washington and His Mother by Frederick Bernays Weiner (American Historical Review, 1991. 26, Vol. 3)