As promised, here are the transcripts from my lecture on the “Gallant Boys of the 123rd” for the 6th Annual Civil War Weekend at the Carnegie-Carnegie Library and Music Hall in Pittsburgh. (I hope to post a video of this talk in the near future.)

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. Before I begin I would like to thank Maggie Forbes, Diane Klinefelter, and the rest of the good folks here at the Carnegie-Carnegie for their wonderful hospitality. I would also like to thank each and every one of you for coming today. Civil War Weekend has become quite an event and it is an honor for me to be here. Back in November, I had the privilege of hosting a premiere for a documentary on Richard Kirkland titled “The Angel of Marye’s Heights.” The response I received was outstanding, so I was absolutely thrilled when Maggie and Diane asked if I would return. Today I am going present some insights on the “Gallant Boys of the 123rd” – the Pennsylvania Volunteers. This will be followed by an exclusive screening of our half-hour documentary and a short Q&A session will follow that.

Both of these topics, the lecture and the film, relate not only to one another, but also directly to the Capt. Thomas Espy Post No. 153 of the Grand Army of the Republic right here at the Carnegie-Carnegie. If you stick around to watch the film later, the men depicted in our reenactments could have very likely been members of the 123rd. Today we are joined in the Music Hall by Pittsburgh author Scott Lang who wrote The Forgotten Charge: The 123rd Pennsylvania at Marye's Heights, Fredericksburg, Virginia. Scott is the REAL expert on the PA Vols. and he has been gracious enough to display his wonderful collection of 123rd relics. Be sure to check those out.

Down in Fredericksburg where I live there are four major Civil War Battlefields. These hallowed grounds include Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, Chancellorsville and The Wilderness. Atop the Fredericksburg Battlefield is a bluff known as Marye’s Heights. The legacy of this location is the focal part of our film, but for my talk we will begin by focusing on what stands there today.

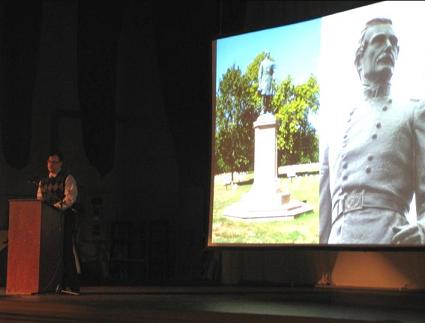

Nowadays atop Marye’s Heights stands a striking monument that commands the center of the Fredericksburg National Cemetery, the final resting place of 15,000 Federal troops who never made it home. This statue portrays General Andrew A. Humphreys and commemorates his Division of Pennsylvania Infantry, the Fifth Corps. Humphrey’s men took place in the Federal Army’s assault at Marye’s Heights and made it to within 100 yards of the Confederate position on this ridge before being cut to pieces and driven back. Theirs was the furthest to advance on this portion of the Army of Northern Virginia’s lines during the Battle of Fredericksburg. On the monument's pedestal read the names of the units that participated in this doomed assault with unparalleled courage and conviction. Included on this list is the 123rd Volunteer Regiment who were mustered out of this region. Many of these men had direct ties to this area either as residents or through family relations.

We know for a fact that there were at least three veterans of the 123rd who survived the war and were members of the Espy Post - right here at the Carnegie-Carnegie. They were: Dennis Gallagher, a member of Company F, who was born in Ireland. After the war he lived in Chartiers. James Harper, a member of Company G, who was born in Washington County and later, lived in McDonald, PA. And William Kirby, a member of Company C, who was born in Allegheny County and settled in Carnegie.

While preparing for this talk I came to the conclusion that there is a very limited amount of materials published specifically on the 123rd. Shortly after the war Samuel Bates wrote a study on the “History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-65” and of course our friend Scott wrote the other. Both of these books served as a valuable reference. That said it would be redundant for me to simply rehash Mr. Bates or Mr. Lang’s findings. I wanted to bring something special to the podium. What I was able to do, through the help of my friends at the National Park Service, was to get the complete transcripts of 4 diaries belonging to members of the 123rd. None of these memoirs have been published to my knowledge and each one is literally a porthole into the past.

Today I will be quoting directly from these diaries, as nothing quite captures the experience of these men more than their own words. Before I do that here is some quick background on the 123rd Volunteer Regiment: They were organized at Pittsburgh, Allegheny City, and Tarentum in August of 1862. They moved to Harrisburg, then to Washington, D.C., where they were attached to the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 5th Army Corps, in the Union’s Army of the Potomac. In 1862 they participated in the: Maryland Campaign (September), Duty at Sharpsburg, MD (October), Movement to Falmouth, VA (October –November) and the Battle of Fredericksburg, VA. (December 12-15). The 123rd would also participate in the infamous 1863 Mud March toward Spotsylvania, and the unsuccessful Chancellorsville Campaign before being mustered out on May 13th of that same year.

Their regimental losses during service were 3 Officers and 27 Enlisted men killed or mortally wounded - and 1 Officer and 41 Enlisted men dead by disease. Total loss over the course of their service was a mere 72 men. That is an amazing number when you look at the engagements that the 123rd participated in. To put that number in perspective: The approximate Union casualties at Antietam: over 12,000 killed or wounded. At Fredericksburg: again - over 12,000 killed or wounded. At Chancellorsville: 17,000 Union men killed or wounded. 72 losses is therefore extraordinary. I would have imagined it to be much-much higher. Perhaps that is a testament to their prowess as fighting men or maybe their luck.

For the purpose of this program let’s focus specifically on their service at Fredericksburg. On a cold winter’s day in December of 1862, Federal forces suffered terrible casualties in several futile assaults against Confederate defenders on the heights behind the city of Fredericksburg. This tremendously one-sided victory renewed the southern force’s resolve while stopping the Union Army’s march toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. The 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteers from Pittsburgh and the surrounding region was right in the thick of it proving that the Steel City’s contribution to the war effort went far beyond the mere production of arms and artillery.

National Park Historian Frank O-Reilly wrote a description of the 123rd’s preparation and entry into battle in his book “The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock.” He wrote: “The 123rd Pennsylvania and the 131st Pennsylvania were in front and the 155th Pennsylvania and the 133rd Pennsylvania behind them. Humphreys ordered his troops to rely on the bayonet and demanded that their weapons be emptied. He had the muskets “rung” (by dropping ramrods noisily into the barrel) to prove they were unloaded. Some of the regiments still carried their gear. …Mounted officers moved to the front. Men touched elbows and roared out of the ravine with a resounding yell.”

At first glance, it sounds like Humphreys is simply ordering his men forward into the fray with no regards for them, but he was actually one of those officers who charged alongside his troops. He once recalled that “For certain good reasons connected with the effect of what I did upon the spirit of the men - and from an invincible repugnance to ride anywhere else - I always rode at the head of my troops.”

Historian Larry Tagg wrote that Lt. Cavada of the general’s staff recalled Humphreys just before he took his troops on the field at Fredericksburg. He stated that: “Humphreys had bowed to his staff in his courtly way, “and in the blandest manner remarked, ‘Young gentlemen, I intend to lead this assault; I presume, of course, you will wish to ride with me?’” Since it was put like that, the staff had done so, and five of the seven officers were knocked off their horses. After his men had taken as much as they could stand in front of the Stone Wall on Marye’s Heights, the next brigade coming up the hill saw Humphreys sitting his horse all alone, looking out across the plain, bullets cutting the air all around him.” He adds, “Something about the way the general was taking it pleased them, and they sent up a cheer. Humphreys looked over, surprised, waved his cap to them with a grim smile, and then went riding off into the twilight. In this way Humphreys had turned his first division’s dislike of him into admiration for his heroic leadership.”

So although the boys of the 123rd were literally marching into a maelstrom of musket fire, they were following a commander who was called upon to be just as courageous as them. It’s really remarkable that he was not shot from his horse – although his horse would eventually be shot out from under him. A diarist from the 123rd who participated in this charge later recalled that as soon as they crested the ridge in front of the Confederate position, stepping into the range of Confederate rifles: “It was then that the balls came thick and fast.” Another stated that the Confederate guns created “such a din as I never wish to hear again.” Soldiers trampled wounded men and horses, and crossed shattered fences. The surroundings, according to one Keystone State volunteer, “were certainly enough to gratify and studios or morbid desire.”

Perhaps the best description comes courtesy of Samuel P. Bates who described it like this: “On the following day the battle opened, and at three P. M., after the corps of Hancock and French had been checked and terribly slaughtered, Humphreys' Division was ordered in. It was a forlorn hope, but gallantly it went forward, and charged again and again those impregnable heights. What brave men dare do, they did; but it was all in vain. No human power could stand against the storm that swept that fatal ground. The One Hundred and Twenty-third occupied a position in the line, with its right reaching nearly to the pike, and bore manfully its part in the battle, suffering grievously. Lieutenant James R. Coulter was among the killed, and Captain Daniel Boisol and Lieutenant George Dilworth among the mortally wounded. The entire loss was twenty-one killed, and one hundred and thirty-one wounded. All night long it lay in position, and through the weary hours of the following day, exposed to a constant fire of the enemy's pickets, and until nine at night, when it was ordered to retire.”

When the smoke cleared after that initial series of assaults, thousands of men has fallen on the field at Fredericksburg, and hundreds more were trapped on the field, unable to retreat or go forward. The area in front of the stone wall at the sunken road became a no-man’s land and sharpshooters continued to pick off survivors who were forced to hide behind the bodies of their dead comrades.

Alexander Altsman, an infantryman in Company E was wounded in the melee and in his diary he wrote of his unfortunate experience at Fredericksburg. On December 13th he writes: “We crossed over the River today the ball and shell were flying through the town, tearing through our ranks William Worthington was struck in the head with a solid shot, but was only stunned our division was put in the fight about sundown.” He continues: “I was the 5th one in our company that was wounded. The following is as correct a list of killed and wounded as I can ascertain: John R Munden - killed David Beatty, Albert Boyce, Chas McTiernan, Henry March, John Stevens, Christian Haber, Samuel Reynolds, William Smith and 1st Lieutenant George Dillworth - wounded. I made my way to the hospital and got my wound dressed but could not get the ball extracted as the doctor could not find it.”

On the 14th he writes: “Did not rest very well last night. Can hobble about a little. The house that we are in now has been very well furnished at one time.” The next day he says, “We were brought over the river this morning, but did not get out of the ambulance until evening.” This is two days after he was shot. Several weeks later – on January 29th, in Washington DC, at Harwood Hospital he finally gets proper medical attention. He writes, “The ball which I received at the Battle of Fredericksburg was extracted this morning. It is a minnie rifle ball and it is bruised a great deal.” So private Altsman is in the 123rd’s charge at Fredericksburg where he is wounded in combat and, over a month later, he is finally relieved of his bullet. In an age of so much death from blood loss and infection, it is amazing to me that he simply refers to the wound’s bruising, like it’s a nuisance.

A comrade in arms named Hugh Hall Stephenson wrote the following series in his diary: December 13th, Saturday: “We went into battle about 3 o’clock and fought till night. List 1 killed and four wounded in Company E. The firing was terrible. Worse than at Antietam.” (That statement is striking as Antietam witnessed bloodshed like no other battle. There 23,000 (yes I said thousand) casualties at that engagement. Over 2100 Confederates - and over 1500 Federal troops killed.) He continues: December 14, Sunday: “Lay on the field all night and all day today. There has been little firing going on all day. At night we were marched back to town and slept in the street.”

Of course in war, not all who are wounded survive the retreat to make it home. James M Watson was another Union soldier who was wounded in the 123rd’s failed assault. Like Altsman, he was hit, and like Stephenson, he was trapped on the field. In fact, Watson was wounded and remained bleeding on the field until the following morning. He would later be removed by an ambulance crew assigned to the 123rd, but would die six weeks later on January 28th, 1863, the day before Altsman had his surgery to remove that ball. So the suffering that these men endured went on long after the rifles and cannons had ceased firing. And that to me personifies the courage and conviction of the Civil War soldier.

In closing today I would like to quote a Union Colonel from the 2nd Brigade named Peter Allebach who sums up the experience of all Pennsylvania Volunteers at Fredericksburg. He writes: “The thought of momentary death rushed upon me and it required every exertion to hush the unbidden fear of my mind. Sulfurous smoke and flame stabbed at the dwindling attackers, leaving the field covered with dead and wounded. We could go no further as the carnage was too fearful.” To put that in perspective Rebel bullets shredded the colors of the 123rd, who later counted 12 large holes in its flag and another through the staff.

Despite facing certain death, the gallant boys of the 123rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment fulfilled their duty to their country and gave it their all in one of the most lop-sided engagements of the entire Civil War. It is therefore our obligation to see that their story and the stories of all participants in America’s “Great Divide” are preserved for future generations. The Capt. Thomas Espy Post No. 153 of the Grand Army of the Republic right here at the Carnegie-Carnegie does this each and every day and I for one am very thankful for their contributions to maintaining Civil War memory.

Updated: Tuesday, 10 May 2011 1:14 PM EDT

Permalink | Share This Post