BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Friday, 18 March 2011

U.S. Marshal Edward Carrington

As a technical-writer for the U.S. Marshals Service, I have the privilege of working with some of the most dedicated people in federal law-enforcement. No other division under the Department of Justice can boast the history of the USMS. From its storied establishment in 1789 by George Washington, to its long list of noteworthy marshals including Frederick Douglass and Wyatt Earp, the USMS is the oldest, and in my opinion, the finest agency in the country. As a Virginia resident I am particularly interested in those who wore ‘the Star’ for my home state.

As a technical-writer for the U.S. Marshals Service, I have the privilege of working with some of the most dedicated people in federal law-enforcement. No other division under the Department of Justice can boast the history of the USMS. From its storied establishment in 1789 by George Washington, to its long list of noteworthy marshals including Frederick Douglass and Wyatt Earp, the USMS is the oldest, and in my opinion, the finest agency in the country. As a Virginia resident I am particularly interested in those who wore ‘the Star’ for my home state.

Edward Carrington was the first United States Marshal for the state of Virginia. Born in Cumberland County in 1748, he was a successful attorney who managed a large plantation as well as his family’s estate. He was also active in politics to the point of becoming a close confidant of George Washington’s. Carrington was approached by Washington to advise him on the growth of Thomas Jefferson’s Republican Party in the Old Dominion. He also provided critiques of potential cabinet candidates and offered opinions on what qualifications should be necessary for political appointments.

As a soldier Carrington served in the First Continental Artillery during the Revolutionary War. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was tasked as the quartermaster-general for Nathaniel Green’s Southern Campaign. During his service Carrington commanded artillery units in engagements against the redcoats at Hobkirk’s Hill and Yorktown. His military service off of the battlefield was equally noteworthy. In addition to being appointed to meet with British representatives to discuss an exchange of prisoners, Carrington was tasked with managing the selling of goods and property confiscated by the Continental Army.

After the British surrendered in 1781, Carrington returned home to practice law and manage his family’s properties. In 1785, and again in ’86, he was nominated as a delegate to represent the state of Virginia at the Continental Congress. In the spring of 1789, Carrington volunteered his services to the new government. Later that year, the United States Marshal Service was established by President Washington who formed the first federal law-enforcement agency under the Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789. Section 27 of that act reads:

And be it further enacted, That a marshal shall be appointed in and for each district for a term of four years, but shall be removable from office at pleasure, whose duty it shall be to attend the district and circuit courts when sitting therein, and also the Supreme Court in the district in which that court shall sit.(b) And to execute throughout the district, all lawful precepts directed to him, and issued under the authority of the United States, and he shall have the power to command all necessary assistance in the execution of his duty, and to appoint as shall be occasion, one or more deputies...

In appreciation for his many years of service, Carrington was appointed as the U.S. Marshal for the District of Virginia at the age of 41. He held the position for a little over 2 years (1789-1791) before he was appointed as the state’s Supervisor of Distilled Spirits.

In 1794, Carrington temporarily retired from public service while maintaining his friendship with Washington. When President John Adams was preparing to raise another volunteer army in anticipation of a war with France, Carrington was named as the supreme commander over an aging Washington. A few months later, America resolved the crisis with France and Washington died of pneumonia.

Carrington remained in Virginia and went on to serve two terms as the mayor of Richmond (1807-1810). During the first year of his first term, he served as the foreman on the jury for the Aaron Burr treason trial. After finding Burr ‘not guilty’ Carrington returned to the mayor’s office where he continued to serve until October 28, 1810, when he died at the age of 62.

References:

USMS website: The First Generation of U.S. Marshals

Congressional Biography: Edward Carrington

Constitution.org: Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789

Hopkins, Garland Evans. Colonel Carrington of Cumberland

Tuesday, 15 March 2011

A History-Mystery

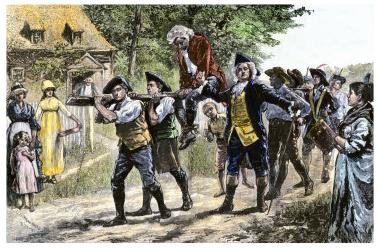

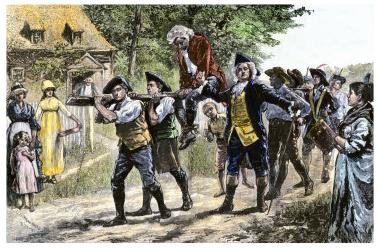

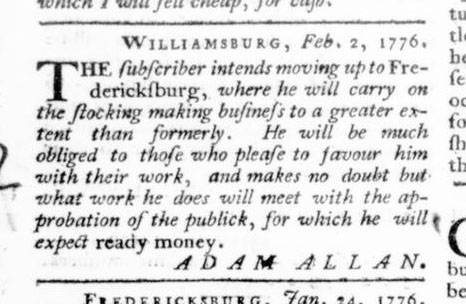

As mentioned below I am researching source-material on the life of a local Loyalist named Adam Allan. While discussing this with Pittsburgh-based historian Tom Byers another Adam Allen was brought to my attention. The Loyalist named “Allan” that I am looking for was born in Great Britain, operated a stocking manufactory, and lived in Williamsburg and Fredericksburg before moving to New Brunswick after being tarred and feathered. Tom’s Loyalist, spelled “Allen,” was born in Scotland, moved to New Brunswick where he enlisted and became a Lieutenant in the Queens Grenadiers in 1779, retaining his commission in 1793 when Britain went to war with France. Both men filed claims for land after the war. So the question remains, is this the same guy?

As mentioned below I am researching source-material on the life of a local Loyalist named Adam Allan. While discussing this with Pittsburgh-based historian Tom Byers another Adam Allen was brought to my attention. The Loyalist named “Allan” that I am looking for was born in Great Britain, operated a stocking manufactory, and lived in Williamsburg and Fredericksburg before moving to New Brunswick after being tarred and feathered. Tom’s Loyalist, spelled “Allen,” was born in Scotland, moved to New Brunswick where he enlisted and became a Lieutenant in the Queens Grenadiers in 1779, retaining his commission in 1793 when Britain went to war with France. Both men filed claims for land after the war. So the question remains, is this the same guy?

It’s quite possible. Tom reminded me that many Loyalists who were tarred and feathered later found their way into a redcoat. He added that the spelling of the name Allan/Allen sometimes gets slipshod in the handwritten record keepings of the 18th c. Another discrepancy he noticed was in their birth-years. One source has ‘Allen’ as being born in 1757, but with handwriting in those days, 1757 could just as easily been 1751 which happens to be when ‘Allan’ was born. What makes this possibility particularly interesting is the notion that Adam Allan/Allen would have certainly had an ax to grind in Virginia. What better way to get revenge than as a soldier in the ranks of the British Army?

So what originally started out as an investigation into the life of a businessman who was subjected to chastisement and forced to flee the town, now has the potential to be the story of a tortured-Tory turned revengeful redcoat. Tom has already directed me to some great sources on Loyalists who enlisted. Stay tuned as the hunt is on to find the REAL Adam Allan/Allen…

Looking at Loyalists

My friend and editor-extraordinaire Benjamin Smith over at Patriots of the American Revolution kindly informed me that my feature “American Gladiators: The Alexander Hamilton-Aaron Burr Duel” will be running in the upcoming July/August issue. My next piece promises to be a bit more challenging. Taking a page from blogger Robert Moore Jr. who has done some excellent work on the Southern Unionists Chronicles, I am interested in examining Virginia’s Loyalists of the Revolution, specifically those here in Fredericksburg.

My previous piece for PAR on the Black Loyalists of New Brunswick was quite broad. This study will take a different approach by examining an individual’s experience. The challenge is finding a good candidate and enough reference material to cover them. In doing some preliminary research, I came upon a Fredericksburg Loyalist whose experiences were particularly unpleasant.

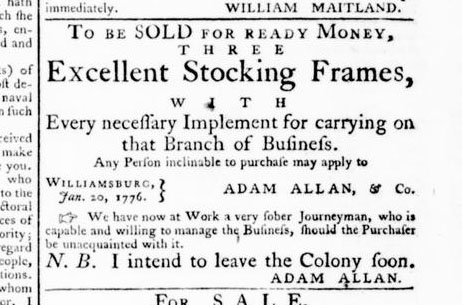

Adam Allan was born in Great Britain in 1751 and originally settled in Williamsburg in 1772. According to an article titled The White Loyalists of Williamsburg by Kevin P. Kelly, “Allan, the proprietor of the Stocking Manufactory, moved to Fredericksburg in February 1776 after making himself very unpopular in Williamsburg by capturing and returning the colony’s seal to Dunmore. But Allan was even less popular in Fredericksburg. He reported that on June 6, 1776, he was ‘stript naked to the waist tarr’d & feather’d’ and in that situation, ‘carted through Fredericksburg upwards of two hours.’ He fled to New Brunswick in 1786.

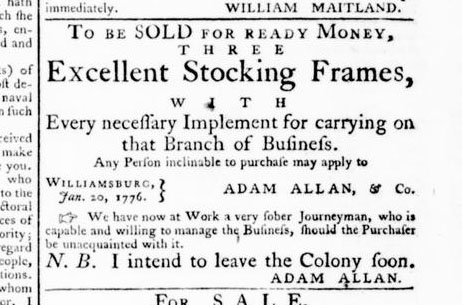

That certainly has the makings of an interesting story. What makes it extremely significant (to me) is the fact that Allan was at one time, a highly-respected businessman in his community, yet he was not exempt from the chastisements that were carried out on Loyalists. This speaks to how quickly residents turned on their fellow citizens who were in support of the Crown. I was able to locate 17 tradesmen newspaper advertisements placed by Allan in 1776.

In the January 20th issue of Dixon and Hunter, a Williamsburg publication, Allan advertises the sale of equipment and journeymen for hire. He closes his ad by stating N.B. I intend to leave the Colony soon.

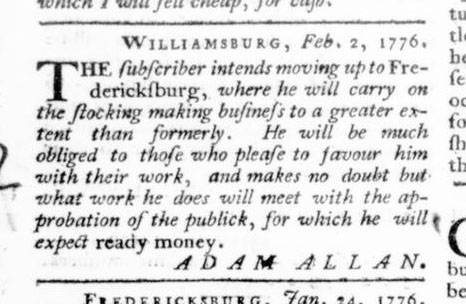

In the February 2nd, 9th, and 16th issues of Purdie, a Fredericksburg publication, Allan announces his arrival:

Williamsburg, Feb 2, 1776.

The subscriber intends moving up to Fre-

dericksburg, where he will carry on

the stocking making business to a greater ex-

tent than formerly. He will be much

obliged to those who please to favour him

with their work, and makes no doubt but

what work he does will meet with the ap-

probation of the publick, for which he will

expect ready money. ADAM ALLAN

Obviously, Mr. Allan was not hiding from the public. I am therefore extremely curious as to what transpired to cause him to leave Williamsburg, why he selected Fredericksburg as a new home, and what events led up to him being tarred and feathered. I will post updates as this project unfolds.

Monday, 14 March 2011

The Soldier’s Parson

Although military chaplains did not exist in an ‘official capacity’ there were instances of clergymen following their flocks into the field during the American Revolution. James Caldwell, also known as “The Fighting Chaplain” was a Presbyterian minister who served with the Continentals as both an army and militia chaplain. Following his graduation in 1759 from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), Caldwell became the pastor at the Elizabethtown Presbyterian Church. His church was burned to the ground by Tories in 1780 setting him on the path towards a new purpose.

Caldwell’s reputation among the troops quickly became legendary following the Battle of Springfield. According to the Library of Congress’ website Religion and the Founding of the American Republic, “At the battle of Springfield, New Jersey, on June 23, 1780, when his company ran out of wadding, Caldwell was said to have dashed into a nearby Presbyterian Church, scooped up as many Watts hymnals as he could carry, and distributed them to the troops, shouting ‘put Watts into them, boys.’”

Tragically the clergyman and his wife were both killed before the war ended. Elizabeth Caldwell was struck down by British gunfire during the Battle of Connecticut Farms. It was reported that she had been shot through the window of their home as she sat with her children on a bed. The circumstances over this “accidental shooting” were disputed. James’ death was equally tragic as he was shot by a Continental sentry after refusing to allow the inspection of a package. The sentry, James Morgan, was hanged for murder after rumors leaked that he had been paid to assassinate the chaplain. With the untimely death of both parents, the nine orphaned Caldwell children were raised by relatives and friends of the family.

Sunday, 13 March 2011

Back to business

I think I’ll give the Tea Party folks a break. “Blog or Die” is supposed to be about real substance, not political commentary. Like my fellow Civil War bloggers who are crusading against the myth of Black Confederates, I will continue to call the TP out for butchering the Revolution. For now, let’s move on…

I think I’ll give the Tea Party folks a break. “Blog or Die” is supposed to be about real substance, not political commentary. Like my fellow Civil War bloggers who are crusading against the myth of Black Confederates, I will continue to call the TP out for butchering the Revolution. For now, let’s move on…

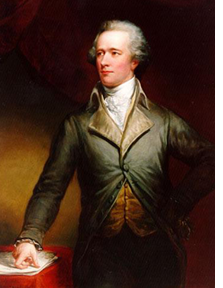

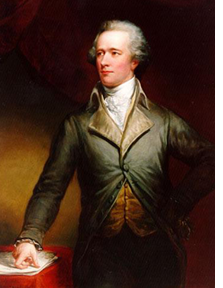

This week I delivered my latest feature for Patriots of the American Revolution on the 1804 Alexander Hamilton- Aaron Burr duel. The article came in just under 4,000 words and presented five components: 1. the background on the strained relationship between Hamilton and Burr, 2. the events that set the duel in motion, 3. the eyewitness account from the attending physician, 4. the post-duel affect on Burr’s public life, and 5. the anti-dueling movement which arose. I included a sidebar with “The Code Duello” under which duels were conducted.

Most folks will be surprised to know that neither men were strangers to dueling, especially Hamilton. His son Philip had been killed three years earlier in a match against George I. Eaker after he and a friend engaged in “hooliganish behavior” in Eaker’s box at Manhattan’s Park Theater. Hamilton had also been the principal in ten shot-less duels from 1770-1779. These included matches against William Gordon, Aedanus Burke, John Francis Mercer, James Nicholson, James Monroe, and Ebenezer Purdy. He acted in the role of second at three other challenges.

By analyzing the accounts, I cannot help but think that Hamilton entered this duel thinking that his adversary would not fire. Without giving away all the details, I will say that there are a number of perplexing questions. Hamilton was a highly regarded military man and Burr was known as being a poor shot. Yet Hamilton shoots high, misses, and tragically dies while Burr manages to hit his target in a manner that mortally wounds. Hamilton's demeanor leading up to the duel is also odd. One item that I did not discuss in the article is the last letter penned by Hamilton. According to the Massachusetts Historical Society:

Alexander Hamilton’s 10 July letter to Theodore Sedgwick of Stockbridge, Mass., is perhaps more notable for what it does not contain, rather than what it does. Writing only hours before he met Aaron Burr on the dueling grounds in Weehawken, New Jersey, Hamilton never mentions his deadly assignation to Sedgwick, nor suggests in any way that this could be his final letter. Instead, Hamilton briefly informs Sedgwick, a fellow Federalist and Massachusetts judge, of his distaste for politics and his negative views of current talk regarding the secession of the New England states and democracy in general. Hamilton writes: “... our real Disease ... is Democracy, the poison of which by a subdivision will only be the more concentrated in each part, and consequently the more virulent.”

Here is the letter in its entirety:

New York July 10. 1804

My Dear Sir

I have received two letters from you

since we last saw each other -- that of the latest date being

the 24 of May. I have had in hand for some

time a long letter to you, explaining my view of the

course and tendency of our Politics, and my intentions

as to my own future conduct. But my plan embraced

so large a range that owing to much avocation, some

indifferent health, and a growing distaste for

Politics, the letter is still considerably short of

being finished -- I write this now to satisfy you,

that want of regard for you has not been

the cause of my silence --

I will here express but one

sentiment, which is, that Dismembrement of our

Empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive ad-

vantages, without any counterballancing good;

administering no relief to our real Disease; which

is Democracy, the poison of which by a subdivision

will only be the more concentrated in each part,

and consequently the more virulent.

King is on his way for

Boston where you may chance see him,

and hear from himself his sentiments --

God bless you

AH

Why didn't Hamilton mention the duel? Perhaps he felt it was a private affair at the time. Maybe he was so used to participating in shot-less duels he felt this one would be equally uneventful. In reading his words, they (in my opinion) come off as sounding frustrated and cynical. He confesses a “growing distaste for politics.” Of course this is only speculation as no one will ever know what he was really thinking the night before he died. You can view a hi-res image of the letter here.

I will post a PDF of the article once it runs in PAR. In the meantime, here’s a YouTube link to some of that substance that I was talking about.

Newer | Latest | Older

As a technical-writer for the U.S. Marshals Service, I have the privilege of working with some of the most dedicated people in federal law-enforcement. No other division under the Department of Justice can boast the history of the USMS. From its storied establishment in 1789 by George Washington, to its long list of noteworthy marshals including Frederick Douglass and Wyatt Earp, the USMS is the oldest, and in my opinion, the finest agency in the country. As a Virginia resident I am particularly interested in those who wore ‘the Star’ for my home state.

As a technical-writer for the U.S. Marshals Service, I have the privilege of working with some of the most dedicated people in federal law-enforcement. No other division under the Department of Justice can boast the history of the USMS. From its storied establishment in 1789 by George Washington, to its long list of noteworthy marshals including Frederick Douglass and Wyatt Earp, the USMS is the oldest, and in my opinion, the finest agency in the country. As a Virginia resident I am particularly interested in those who wore ‘the Star’ for my home state.

As mentioned

As mentioned

I think I’ll give the Tea Party folks a break. “Blog or Die” is supposed to be about real substance, not political commentary. Like my fellow Civil War bloggers who are crusading against the myth of Black Confederates, I will continue to call the TP out for butchering the Revolution. For now, let’s move on…

I think I’ll give the Tea Party folks a break. “Blog or Die” is supposed to be about real substance, not political commentary. Like my fellow Civil War bloggers who are crusading against the myth of Black Confederates, I will continue to call the TP out for butchering the Revolution. For now, let’s move on…