Christmas and slavery at Monticello

Although Thomas Jefferson’s Bible presents a non-traditional view on the birth of Jesus, Christmas celebrations were still held at Monticello and Poplar Forest acknowledging the Christian holiday. In 1762, Jefferson described Christmas as “The day of greatest mirth and jollity” and both friends and family wrote about the decorating of evergreen trees and the hanging of stockings. Christmas was also a time of change for Monticello’s slave population.

According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation: “For African-Americans at Monticello, the holiday season represented a time between - a few days when the winter work halted and mirth became the order of the day. The Christmas season came to represent hours when families reunited through visits and when normal routines were set aside. In 1808, Davy Hern traveled all the way to Washington where his wife Fanny worked at the President’s House to be with her for the holidays. Two days before the Christmas of 1813, Bedford Davy, Bartlet, Nace, and Eve set out for Poplar Forest to visit relatives and friends. Enslaved people frequently recalled that Christmas was the only holiday they knew. Many cherished memories of gathering apples and nuts, burning Yule logs, and receiving special tokens of food and clothing.”

The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia provides the following list of 'Christmas in the Enslaved Community' primary source references:

- 1790 December. (Nicholas Lewis, Monticello steward, accounts in Ledger 1767-1770). “To 2 1/2 Gallons Whiskey at Christmass for the Negroes.”

- 1797 December 2. (Jefferson to Maria J. Eppes). “Tell Mr. Eppes that I have orders for a sufficient force to begin and finish his house during the winter after the Christmas holidays; so that his people may come safely after New year's day.”

- 1808 November 17. (Edmund Bacon to Thomas Jefferson). “Davy Has Petitioned for leave to come to see his wife at Christmass.”

- 1808 November 22. (Jefferson to Edmund Bacon). “I approve of your permitting Davy to come [to Washington] at Christmas.”

- 1810 August 17. (Jefferson to W. Chamberlayne). “I agreed to take them [hired slaves] at that price and they were to come to me after the Christmas Hollidays when their time with him was out.”

- 1813 December 24. (Jefferson to Patrick Gibson). “We shall begin to send [flour] from hence immediately after the Christmas holidays.”

- 1814 December 23. (Jefferson to Jeremiah Goodman, overseer). “Davy, Bartlet, Nace and Eve set out this morning for Poplar Forest. Let them start on their return with the hogs the day after your holidays end, which I suppose will be on Wednesday night [Dec. 28], so that they may set out Thursday morning.”

- 1818 December 24. (Joel Yancey, Poplar Forest, to Jefferson). “Your two boys Dick and Moses arrived here on Monday night last [Dec. 21]. Both on horse back without a pass, but said they had your permission to visit their friends here this Xmass.”

- 1821 December 27. (Mary Jefferson Randolph to Virginia Jefferson Randolph). “This Christmas has passed away hitherto as quietly as I wished and a great deal more so than I expected. I have not had a single application to write passes or done or seen any of the little disagreeable business that we generally have to do and except catching the sound of a fiddle yesterday on my way to the smokehouse and getting a glimpse of the fiddler as he stood with half closed eyes and head thrown back with one foot keeping time to his own scraping in the midst of a circle of attentive and admiring auditors I have not seen or heard any thing like Christmas gambols and what is yet more extraordinary have not ordered the death of a single turkey or helped to do execution on a solitary mince pie wo you see you lost nothing by being on the road this week.”

Although Christmas did not represent physical freedom for Monticello’s slave population, it could provide an opportunity for spiritual freedom, as well as the hope for better things to come. According to his records, Jefferson granted a four-day holiday at Christmas in which slaves could visit with friends and family in the community. Christmas was also one of the two times during the year that Jefferson would provide cloth to his slaves for clothes.

Like most masters, Jefferson increased his slave’s food rations during this time and on occasion, provided whiskey. During the brief sabbatical Monticello’s slaves had the freedom to hold their own services and celebrations, which included the same merriment as their white counterparts. This included singing and dancing. There are no records that indicate that Thomas Jefferson attended any of these events, but Isaac Jefferson once recalled that his brother would “come out among the black people, play the fiddle and dance half the night.”

Christmas on Mulberry Row is one of the most striking examples of the complex and contradictory nature of the master-slave relationship at Monticello. Despite its apparent hypocrisy, the holiday season represented a time when enslaved African-Americans could exercise a little levity and celebrate the birth of our Lord and savior.

I would like to take this opportunity to wish all of my readers a very Merry Christmas. God bless.

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 10:30 AM EST

Updated: Wednesday, 22 December 2010 10:53 AM EST

Permalink |

Share This Post

My Black Confederate Contribution

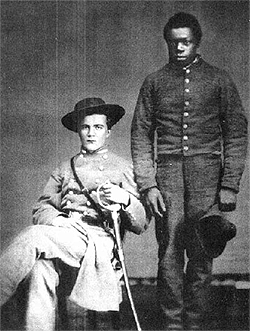

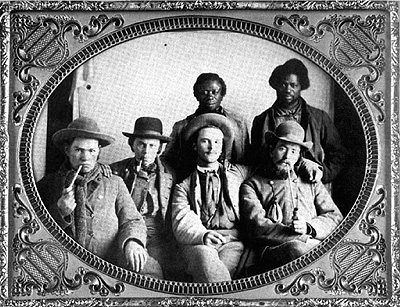

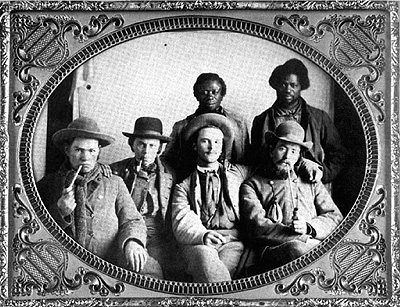

Members of the 7th Tennessee Cavalry and their slaves. (Tom Farish Collection)

Over the last few years the subject of race has become of particular interest to me. Its impact on history first came to my attention when (as co-founder of The Jefferson Project) I participated in a multi-racial project titled What Black History Month Means to Me for The Free Lance-Star. In my regional book on Fredericksburg’s historical churches, I included a comparison of the black and white Baptist congregations which later evolved into a lecture titled Houses of the Holy: A Study in Pre-War Race Relations. This talk was very well received and I last presented it at Manassas Museum. Since then I have penned several features for Patriots of the American Revolution that dealt with the subject of race in the past and present.

Although this subject was newfound territory for me, several of my associates had been writing about it for quite some time. Our good friend Richard Williams had authored a tremendous book on the first black Sunday school in Lexington titled Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man’s Friend. This narrative was later turned into the documentary Still Standing, The Stonewall Jackson Story. Following Richard’s lead, I no longer avoided subjects that I found uncomfortable. Since then race, and more importantly, racism, has become a crucial element when examining our nation’s origin. How could it not be? As an historian focusing on the Colonial-era it would be impossible for me to present anything of merit on the Founding Fathers while ignoring their practice of slavery. We must acknowledge the hypocrisy that existed within the Founders own struggle for independence as they were guilty of withholding liberty from an entire race of people. This is the complexity that is early-American history and the struggle between the races becomes even more complicated during the Civil War.

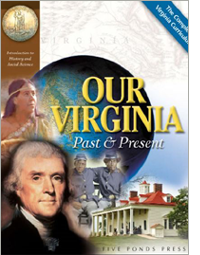

One race-related topic that has become THE debate among historians and enthusiasts is the ongoing argument over the existence of black confederates. Much of this sudden interest has come in retaliation to recently published claims that thousands of African-Americans served in the southern ranks as equal combatants. The subject of black confederates even won nationwide attention after a 4th-grade VA history book was issued to students with the claim that thousands of blacks fought for the Confederacy and that two black battalions fought under Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson. As one who has written quite a bit of material on the general, to include dozens of articles and a short biography, I can say that I never-ever read anything that even remotely alluded to this.

One race-related topic that has become THE debate among historians and enthusiasts is the ongoing argument over the existence of black confederates. Much of this sudden interest has come in retaliation to recently published claims that thousands of African-Americans served in the southern ranks as equal combatants. The subject of black confederates even won nationwide attention after a 4th-grade VA history book was issued to students with the claim that thousands of blacks fought for the Confederacy and that two black battalions fought under Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson. As one who has written quite a bit of material on the general, to include dozens of articles and a short biography, I can say that I never-ever read anything that even remotely alluded to this.

I don’t even know how anyone could accidentally misquote that. Still there are supporters that swear up and down that this is the gospel and that similar claims are true. Some proponents even claim that there is a modern conspiracy to keep African-Americans from getting the credit they deserve in the fight for southern independence.

My only contribution to this heated-discussion comes in the form of a chapter that I included in my book The Civil War in Spotsylvania: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads. In my research of hundreds of letters pulled from the archives at the Fredericksburg/Spotsylvania National Military Park, I found one instance that mentioned an African-American acting in a combatant role and zero claims of any groups of black confederates fighting in any of the four major battles. I did find several letters that discussed blacks acting in the role of body servants and camp slaves and one mention of a former servant receiving a post-war pension. All of these findings are included in the book. My own summation is that there were no black southern soldiers fighting in mass in any of the four regional campaigns.

I do acknowledge the service of Levi Miller, which has been validated by the folks here at the NMPS, but there is a BIG difference between one black slave acting in the capacity of a soldier and 'thousands' for sure. I can say this with total confidence as there is no evidence that I am aware of that supports these numbers.

Still, there are people who come up to me at book signings and want to argue that tens of thousands of blacks donned the gray kepi and willfully went off to war to fight the Yankee invader. Some of these people have an agenda, but many others are just misinformed. I try to be as polite as possible and it’s hard to argue with someone that is so adamant in their beliefs. Perhaps that is why I have been writing so much about this subject in regards to the Revolution. Simply put, you can’t argue about the slaves at Monticello or the black loyalists of New Brunswick.

Frankly, it was the controversy over the VA textbook that caught my attention. The idea that this kind of misinformation could spread into an approved curriculum was startling to say the least. That event in particular made me aware of how dangerous this situation is. My children go to school in Virginia where this textbook was released and I would have been horrified to read its account claiming that: “thousands of Southern blacks fought in the Confederate ranks including two black battalions under the command of Stonewall Jackson.”

In response to this claim I am posting a portion of my only published writing on black confederates, so that I can go to sleep at night knowing that I shared my few findings with the general public. Levi Miller's story is unique and the two letters that are also included in the chapter describe the cooking and laundry services provided by Confederate slaves.

Excerpt from The Civil War in Spotsylvania County, Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads by Michael Aubrecht (The History Press, 2009)

Excerpt from The Civil War in Spotsylvania County, Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads by Michael Aubrecht (The History Press, 2009)

Colored “Confederates”

Black Cooks, Body Servants and Slaves

Bill is as well pleased as any Negro you ever saw, he has been to three negro Balls since we arrived at these camps, but he would go off without first asking permission. —W. Johnson J. Webb, Company I, 51st Georgia Volunteer Infantry.

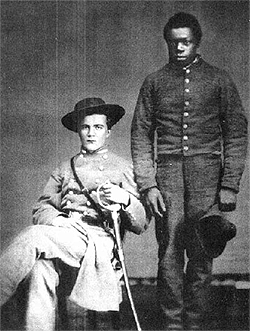

Throughout the course of the war, Confederate officers routinely brought their slaves with them to act as camp servants and mess cooks. This was done as both a reflection of the officers’ social status and for the domestic services provided by the slaves. In some cases, these African Americans would be issued uniforms, and their typical responsibilities included cooking, washing clothes and cleaning quarters. In addition, those slaves with a musical talent were often called upon to sing, dance and play tunes to entertain their masters’ staff or messmates. The sincere nature of these relationships is required to be judged on an individual basis, but it is fair to say that the overwhelming majority of blacks in Confederate camps were most likely acting in the role of servants rather than soldiers. ABOVE: Studio shot of a Confederate officer and his body servant (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

One of these rare individuals who is said to have served in both capacities was Levi Miller. Born in Rockbridge County, Miller accompanied his master into the field as a body servant and was later called upon to nurse him back to health following a serious wounding at the Battle of the Wilderness. Following his master’s recovery, Miller is said to have been voted into the regiment as a full-fledged member. He is then said to have fought in multiple engagements, with the most notable occurring at the bloody Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse.

According to an account by Captain J.E. Anderson, Miller served with courage and honor. He wrote, “About 4 p.m., the enemy made a rushing charge. Levi Miller stood by my side—and man never fought harder and better than he did—and when the enemy tried to cross our little breastworks and we clubbed and bayoneted them off, no one used his bayonet with more skill, and affect than Levi Miller.” Following the South’s surrender, Miller received a pension from the State of Virginia as a veteran.

An article printed in the Fredericksburg papers stated that one of the longest surviving Confederate body servants was a local man named Cornelius S. Lucas. In captivity, Lucas had belonged to William Pollock of Stafford County, who served in Company H, 47th Regiment, Virginia Infantry. Upon receiving his freedom, Lucas became a minister and eventually operated a coffeehouse and store in the downtown district. It is believed that he too received a pension for his time with the army, as well as a certificate of appreciation from the local United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter.

Some blacks served the entire war in a loyal capacity to their owners, while others escaped the binds of slavery to find freedom across the Union lines. When the Federal army occupied an area, local slaves would use that opportunity to seek refuge among them, some even acting in the capacity of teamsters or stretcher-bearers. Others would enlist as soldiers and return to fight as members of the U.S. Colored Troops. One Fredericksburg widow named Jane Beale commented in her diary on May 12, 1862, about the mass exodus of blacks toward the Northern army. She wrote, “The enemy has interfered with our labour by inducing our servants to leave us and many families are left without the help they have been accustomed to in their domestic arrangements. They tell the servants not to leave, but to demand wages.”

Regardless of their roles, or personal motives and loyalties, African Americans on both sides of the conflict served with the same courage and distinction as their white counterparts, whether acting in the capacity of soldier, servant or slave.

Letter from John McDonald of the 13th Mississippi Infantry to his wife:

Camp near Fredericksburg

March 30th, 1863

Well Susan I will resume the writing of my letter by telling you that yesterday and to day is verry cold ice is a quarter of an inch thick this morning I told you last night what I have done before I begun my letter so I will tell you what I have done this morning. the first thing you know is to get out of bed. the next I brought a bucket of water and wash my face and hands and then folds up the blankets while the other boys cooked a little breakfast and then we joined in and washed our clothes this may surprise you so I will tell you something about it. You see when Rose Williams came back he brought some of his friends with him to go in the same mess. and that made the mess too large so I and Martin Willis Jo Walters and Adam Ulmer seceded from the old mess and the negro that had been doing our washing belonged to Rose, of course the negro then would go with the other mess so we thought that we could gain by doing our own washing rather than to pay 25 cents a garment which would cost me about 75 cents a week enough of this stuff Susan we are still at Fredericksburg tomorrow is the last day of March. I don’t see any sign of the buds of trees puting out yet and neither do I see any signs of peace the Yankees are still in sight across the Rappahanoch River…

John McDonald

Four slaves prepare a kettle meal near Confederate artillerymen.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Recollections of Robert Wallace Shand, Company C, 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry:

John Clarkson of our mess had a negro man named Mander who cooked for us and served our mess. We chipped in and got a horse and wagon and foraging was easy, for the county around was rich in food stuffs. The beef was magnificent drawn largely from Loudon County, which was a garden spot. Chickens, ducks, butter, eggs, buttermilk etc were easily obtained and we fared sumptuously every day. Meantime, we went diligently thro’ all the routine of Camp-life. Reveille beat at dawn of day which comes sooner there than in Columbia in June—and later in December. After roll call the boys proceeded to cook their breakfast, but as our mess had a servant we went to sleep again. After breakfast was guard mounting, then company drill, recreation, cooking, dinner, battalion drill, dress parade, cooking, supper, tattoo, sleep. I may here note that on marches and while under arms expecting a fight, a few were detailed to cook for all, and sometimes it happened that there was no cooking at all because there was nothing to be cooked. Guard was divided into three squads, each (called a relief) was on two hours and off four but when off were kept at the guard tent. Details were sent up every day from the ten companies. Each relief had a corporal, and for the whole there was one sergeant, and a lieutenant who was officer of the guard. Each captain in turn was officer of the day. I do not remember how long it was between the times that my turn came. It probably varied on account of absences, sickness and extra duty men. I remember that one night the countersign was “Austerlitz.” I told the corporal that our illiterate men would not remember that word. Sure enough the sentinels kept it lively that night. “Corporal of the guard post #3” and “corporal of the guard post #8” etc., and the call was to ask the corporal to tell them again what the countersign was.

On 18 November we again took up our march and covered a distance of 13 miles which took us across the Rapidan at Raccoon Ford on the road to Fredericksburg. The regiment camped the next night at Chancellorsville and on the evening of the 20th went into camp two miles out of Fredericksburg. But on 19th I broke down, and keeping Edwards with me, lost our way, stayed all night with a Mrs. Mason, and reached Chancellorsville in a heavy rain on the afternoon of the 20th. where we stopped, and spent the night in the large house of Mr. Chancellor. After supper two soldiers asked for sleeping quarters. Mr. C. said his house was full and therefore he was sorry that he could give them no place except the loft of his stable. He went out to show them the way, and we wondered whether we would have to take the wagon shed, but when we made the same request of him on his return, he said he could give us a mattress on the floor of the dining room. And there we slept comfortably all night. The next evening we rejoined our company in camp.

During all the months of my service, what was camp life? I have mentioned guard mounting (p. 32) and our drills (p. 56). At guard mounting (or troupe) every morning, the 2d Sergeant took the sick and ailing ones to the Surgeon at the hospital tent, who diagnosed and prescribed—the latter according to stock on hand. The noncommissioned officers and men had to get their own wood and water, do their own cooking and washing. and keep their guns clean. The officers had servants for these duties. Until after Sharpsburg, old Manders slave to John Clarkson, did most of these duties for us. He also was a good provider. When we stopped, he would go off and come back with chickens etc. for most of which we paid, but sometimes the old fellow (who was too honest to steal) would “impress” them, or, to use his own phrase, “pressed em.” But a disagreement broke up our mess and thereafter, Edwards, Bryce and I slept together, did our own cooking, toting etc.

Robert Wallace Shand

Sources:

Fredericksburg/Spotsylvania National Military Park Service archives:

BV# 080-02: Letters of John McDonald, 13th Mississippi.

BV# 162-04–162-05: Incidents in the life of a Private Soldier in the War Waged by the United States against the Confederate States 1861–1865. Robert Wallace Shand, Co. C., 2nd SCV (SC Library).

One race-related topic that has become THE debate among historians and enthusiasts is the ongoing argument over the existence of black confederates. Much of this sudden interest has come in retaliation to recently published claims that thousands of African-Americans served in the southern ranks as equal combatants. The subject of black confederates even won nationwide attention after a

One race-related topic that has become THE debate among historians and enthusiasts is the ongoing argument over the existence of black confederates. Much of this sudden interest has come in retaliation to recently published claims that thousands of African-Americans served in the southern ranks as equal combatants. The subject of black confederates even won nationwide attention after a