BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Wednesday, 31 March 2010

Edits and Egos

This week I am busy fine-tuning the article version of my talk about Mary Ball Washington for Patriots of the American Revolution. The final word count was around 3,000 and I found some excellent sources for illustrations including several books published in the 1880’s. This 20-minute speech is rapidly growing into a much larger and more scholarly project. In addition to the upcoming feature in PAR, I am also giving a 1-hour presentation on George’s mother to the Stafford County Historical Society in October. I also anticipate posting the video version of this from the VA Farm Bureau Women’s Conference next week. (Stay tuned)

My commute has me casually reading through Benjamin Franklin: An American Life by Walter Isaacson and I am gaining a whole ‘new’ perspective on Dr. Franklin. Much like his associates John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, Franklin was also a brilliant, multi-talented entrepreneur. Unlike them, he also appears to have held the nefarious title of “playboy.” Let’s just say that Benjamin Franklin was a very busy man…who stayed busy…in three countries.

Although I have zero interest in his sex life, I am very interested in how he handed personal relationships. More specifically, I am interested in the personal and political relationships between Franklin and Adams and Jefferson. These three egos in one room must have been a sight to behold. I have read that there was a mutual respect and competitive spirit surrounding their kinship, as well as periodic animosity.

The first sign of tension between these giants may have come during their early collaboration on the Declaration of Independence. As the most eloquent writer of the group, Jefferson was tasked with authoring the first draft, which was then reviewed by Adams and Franklin. Both critics were adamant that a document of this magnitude could not be created in it’s entirely by one man. Their fellow colleagues from the Continental Congress also injected their opinions, which in turn, led to protesting from the original author.

As portrayed in the HBO Mini-Series John Adams, Jefferson is said to have been visibly apprehensive with the editorial comments made by his peers. I was curious as to the level of “apprehension,” so I did some research into this episode and found an account that was written by Franklin’s grandson, William Temple. It was later published in William Temple’s Diary: A Tale of Benjamin Franklin’s Family In the Days Leading up to The American Revolution. It reads:

June 23, 1776

The awesome day has come and gone. Father made the proposed “tenderness and delicacy” impossible. In no uncertain terms, he told the Provincial Congress that they were an illegal body, definitely not representative of the population of New Jersey. He called them “pretended patriots,” “insidious malcontents bent on replacing British liberty with Republican tyranny.” He refused to answer the questions asked by the President of Congress. At some point, Mr. Witherspoon, President of Princeton College, lost his temper and alluded sarcastically to Father’s “exalted birth.” It was finally decided, with the approval of the Philadelphia Continental Congress, that the governor should be removed from New Jersey and sent under guard to the custody of Governor Trumbull in Connecticut. Exactly what Father had predicted!

As my aunts shed copious tears, I wondered whether this was Father at his worst — unbearably arrogant — or at his best — true to himself, whatever the cost. “To thine own self be true...” a nice Shakespeare quotation that might comfort Aunt Jane in a calmer moment.

On the very day of Father’s trial, Grandfather, now back home and feeling much better, was looking over Mr. Jefferson’s draft of a Declaration of Independence. Mr. Thomas Jefferson, a tall, lanky man with reddish hair, lives only a couple of blocks from us on Market street. The motion for such a Declaration was proposed some time ago by a fellow Virginian, Richard Henry Lee, but is acted upon only now. Known to be an excellent writer, Mr. Jefferson, also a Virginian, was quite upset by the many changes to his text suggested by various congressional colleagues. Grandfather told me that he had recommended only one important change. In the introductory sentence, “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable...” Grandfather suggested replacing those two qualifiers by the word self-evident, and Jefferson agreed.

BELOW: Jefferson's original draft of the Declaration with Adam’s and Franklin’s marks. (Source: Independence Hall Association) View an enlarged and legible version of the draft at Constitution.org.

Friday, 26 March 2010

Drummer Men?

Throughout the history of warfare musicians have always played an important role on the battlefield. Military music has served many purposes including marching-cadences, bugle-calls and funeral dirges. Fifes, bagpipes and trumpets are just some of the tools that were used to instruct friend and intimidate foe.

Throughout the history of warfare musicians have always played an important role on the battlefield. Military music has served many purposes including marching-cadences, bugle-calls and funeral dirges. Fifes, bagpipes and trumpets are just some of the tools that were used to instruct friend and intimidate foe.

Perhaps the most notable of these instruments was the drum. From as far back as the ancient days of Babylon, percussion rallied the troops on the field, sent signals between the masses, and scared the enemy half to death. During the Revolutionary War, drummers in both the Continental and English ranks marched bravely into the fight with nothing but their rudiments and sticks to protect them.

Remarkably, some of these musicians were in fact, very young boys, not quite yet into their teen years. That group however, was a minority. Despite popular culture’s portrayal of the little “Drummer Boy,” boys were actually an acceptation to the rule in early American warfare. According to The music of the Army... An Abbreviated Study of the Ages of Musicians in the Continental Army by John U. Rees (Originally published in The Brigade Dispatch Vol. XXIV, No. 4, Autumn 1993, 2-8.):

Boy musicians, while they did exist, were the exception rather than the rule. Though it seems the idea of a multitude of early teenage or pre-teenage musicians in the Continental Army is a false one, the legend has some basis in fact. There were young musicians who served with the army. Fifer John Piatt of the 1st New Jersey Regiment was ten years old at the time of his first service in 1776, while Lamb's Artillery Regiment Drummer Benjamin Peck was ten years old at the time of his 1780 enlistment. There were also a number of musicians who were twelve, thirteen, or fourteen years old when they first served as musicians with the army.

Sixteen years, although young by today’s standards, was considered the mature age of a young man in the days of the American Revolution. It was also the average age of many fifers and drummers who marched in the ranks of Gen. Washington’s army. For example the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment boasted the following musician’s roll:

John Brown, fife - 14 years old, enlisted in 1777 (11 years in 1777)

Thomas Cunningham, drum - 18 years old, enlisted in 1777 (15 years in 1777)

Benjamin Jeffries, drum - 15 years old, enlisted in 1777 (12 years in 1777)

Robert Hunter, drum - 40 years old, enlisted in 1777 (37 years in 1777)

Thomas Harrington, drum - 14 years old, enlisted in 1777 (11 years in 1777)

Samuel Nightlinger, drum - 16 years old, enlisted in 1777 (13 years in 1777)

James Raddock, fife - 16 years old, enlisted in 1777 (13 years in 1777)

George Shively, fife - 19 years old, enlisted in 1777 (16 years in 1777)

David Williams, drum - 17 years old, enlisted in 1777 (14 years in 1777)

Despite their non-violent role in battle, many of these drummer’s war stories are even more compelling than those of the fighting men around them. For instance, Charles Hulet, a drummer in the 1st New Jersey…The following deposition was given by Hulett's son-in-law in 1845:

"... said Hulett... enlisted in Captain Nichols company [possibly Noah Nichols, captain in Stevens' Artillery Battalion as of November 9, 1776. In 1778 he was a captain in the 2nd Continental Artillery. See entry for Joseph Lummis] which was a part of the first Regiment of New Jersey in the service of the United States which Regiment was commanded by Col. Ogden. He enlisted as aforesaid on the 7 May 1778... He was engaged in the battle of Monmouth and was wounded in the leg and then or soon after taken a prisoner and by the enemy and carried in captivity to the West Indies, To relieve himself from the horrors of his imprisonment he joined the British Army as a musician and was sent to the United States. That soon after his return... he deserted from the British ranks and again joined the army of the United States and the south under General Greene. He was present at the siege of York and after the surrender of Cornwallis he was one of the corps that escorted the prisoners which was sent to Winchester... and he remained in service to the end of the war. This declarant always understood that said Hulett at the close of the war held the rank of Drum-Major."

For a detailed study, visit The music of the Continental Army....

Illustration by Donna Neary, from Raoul F. Camus, Military Music of the American Revolution. (Chapel Hill, NC, 1976).

PS: Your blogger drummer marching off to war in 1978.

Wednesday, 24 March 2010

And Justice For All

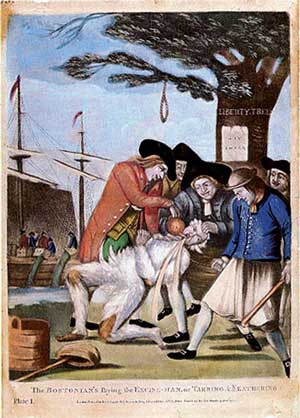

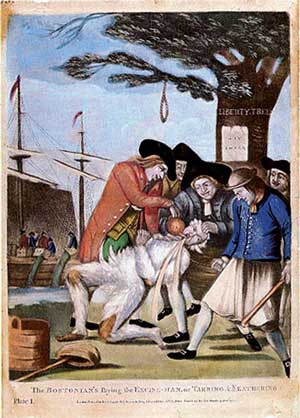

ABOVE: “The Bostonians Paying the Excise Man.”

(1774 print, attributed to P. Dawe.)

Chastisement in the pursuit of justice remains one of the most hotly contested and debated issues of the day. From capital punishment to humiliation practices, consequences suffered by those who commit crimes are intended to set an example. The debate lies in how far one can go in the pursuit of righteousness. Many citizens today believe that more criminals deserve to be rehabilitated rather than incarcerated, while others rally for harsher and lengthier sentences. Recent accusations of torture and inhumane interrogation techniques have reopened the public’s examination of how prisoners should, and should not, be treated.

In the early days of primitive America, vigilante justice, or “mob rules,” commanded the streets as angry citizens took it upon themselves to act as judge, jury, and in some cases, executioner. Many of the methods used at this time were exceptionally painful and permanently scarring. Some of the harshest punishments can be traced back to the crown, hundreds of years before any Englishman ever set foot in the New World. Perhaps the most disturbing form of retribution to be dispensed in the colonial era was the act of tarring and feathering. This was an unsanctioned penalty in which an individual would have boiling hot tar poured over or brushed onto them, then they would be either covered in - or rolled in - feathers. Sometimes the person would be stripped naked and carried around town upon a rail. The goal was to humiliate them to the point that they would vacate the town, never to return.

This painful procedure was originally endorsed by English law in the late 1100’s. The earliest mention of “official” tar and feathering occurred in the orders of King Richard I of England, who issued them to his navy before sailing for the Holy Land in 1191. It is believed that this primitive ordinance aimed at criminal crusaders inspired the use of the technique in the colonies during the turbulent days leading up to the revolution. What follows is a transcript of what is believed to be the only royal declaration in existence that specifically instructs the use of tar and feathering:

Laws of Richard I (Coeur de Lion) Concerning Crusaders Who Were to Go by Sea. 1189 A.D. ("Roger of Hoveden," III p. 36 [Rolls Series].)

Richard by the grace of God king of England, and duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, and count of Anjou, to all his subjects who are about to go by sea to Jerusalem, greeting. know that we, by the common counsel of upright men, have made the laws here given. Whoever slays a man on ship. board shall be bound to the dead man and thrown into the sea. But if he shall slay him on land, he shall be bound to the dead man and buried in the earth. If any one, moreover, shall be convicted through lawful witnesses of having drawn a knife to strike another, or of having struck him so as to draw blood, he shall lose his hand. But if he shall strike him with his fist without drawing blood, he shall be dipped three times in the sea. But if any one shall taunt or insult a comrade or charge him with hatred of God: as many times as he shall have insulted him, so many ounces of silver shall he pay. A robber, moreover, convicted of theft, shall be shorn like a hired fighter, and boiling tar shall be poured over his head, and feathers from a cushion shall be shaken out over his head,-so that he may be publicly known; and at the first land where the ships put in he shall be cast on shore. Under my own witness at Chinon.

Source: Henderson, Ernest F.

Select Historical Documents of the Middle Ages

London: George Bell and Sons, 1896

Sunday, 21 March 2010

What a weekend.

This weekend I had a great time visiting with my friend Mort Kunstler (View a PDF of my FLS article) and speaking at the VA Farm Bureau Women’s Conference on the life and legacy of Mary Ball Washington. It was clearly the largest room that I have done to date (300+ attendees) and I will be receiving a copy of the video that was recorded for broadcast to post here. The feedback that I received on this particular piece was extremely encouraging. As a result, I will be submitting a more scholarly and in-depth version to Patriots of the American Revolution for inclusion in an upcoming issue. Stay tuned for the VAFB video which will be posted upon receipt. I would like to add that Virginia's farmers deserve our thanks and support. If you like to eat, remember where it comes from.

This weekend I had a great time visiting with my friend Mort Kunstler (View a PDF of my FLS article) and speaking at the VA Farm Bureau Women’s Conference on the life and legacy of Mary Ball Washington. It was clearly the largest room that I have done to date (300+ attendees) and I will be receiving a copy of the video that was recorded for broadcast to post here. The feedback that I received on this particular piece was extremely encouraging. As a result, I will be submitting a more scholarly and in-depth version to Patriots of the American Revolution for inclusion in an upcoming issue. Stay tuned for the VAFB video which will be posted upon receipt. I would like to add that Virginia's farmers deserve our thanks and support. If you like to eat, remember where it comes from.

Via email: I thoroughly enjoyed your presentation and perspective on Mary Ball Washington. That was the fastest half hour of history I have attended! For me, you could have gone on the rest of the morning.

Doug Stoughton

Director, Women and Young Farmer Department

Virginia Farm Bureau Federation

Thursday, 18 March 2010

May I take your coat sir?

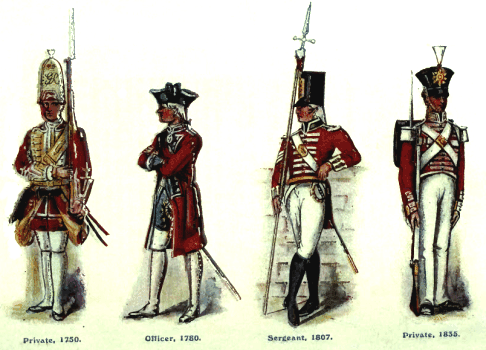

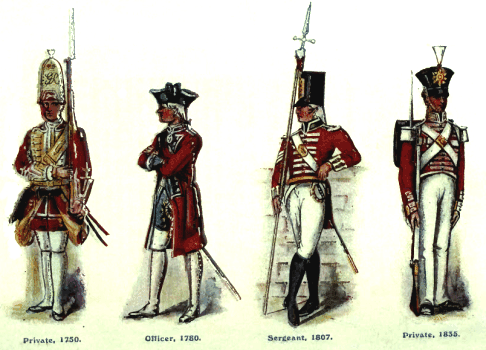

ABOVE: British Army infantry uniforms from 1750 to 1835.

Source: Regimental Nicknames and Traditions of the British Army. (London: Gale & Polden. 1916.)

Today I thought I would share something a little more casual and just for fun… My father has a tremendous collection of records which include a complete set of Bill Cosby’s comedy albums. A good part of my childhood memories include scenes of the family, sitting around the old stereo, listening to some of the funniest bits ever captured on vinyl. One of my favorites is a record titled “Bill Cosby is a Very Funny Fellow Right?” (or something like that). There is a routine from that performance in which Cosby pitches the concept of a referee holding a coin toss at the beginning of a war. He uses the American Revolution as the basis, and after making the right call, the Continentals choose to ‘kick off,’ and add that “We can wear whatever color uniforms we like, and hide behind trees and rocks and stuff, and you British have to wear bright red, and march out in the open in a straight line.” That punch-line stuck with me and even to this day, every time I see a depiction of a Redcoat, that joke enters my mind. What makes it so funny is that it’s true.

Clearly the Brits had far better tailors than the Continentals, but form over function has never worked on the battlefield. In their quest to look their best, many of the King’s finest suffered death by wardrobe. We know this as there have been studies by military historians that cite the affect of heavy and cumbersome uniforms on the army. They have determined that the regulation style uniforms worn by the English troops contributed to needless suffering en route to defeat. There was even an episode of “Battlefield Detectives” on the History Channel in which they concluded that a group of British soldiers who were cut off from any shade or water supplies were beaten by a much smaller force of militia, who pinned them in and simply prevented them from moving (in a siege like state). As the hours passed their enemy fell into a deadly state of heat exhaustion and dehydration. The investigators even went so far as to put two modern-day British Commandos on treadmills, one in the sparse attire worn by the minutemen and the other in a traditional garb worn by English infantry. The Continental fared well, while the Redcoat almost passed out. (Of course the opposite was true in the winter-months and the rebels lightweight gear left much to be desired at places like Valley Forge.)

According to excerpts cited from "History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army" by Maj. R.M. Barnes, “The red coat has evolved from being the British infantryman's ordinary uniform to a garment retained only for ceremonial purposes. Its official adoption dates from February 1645, when the Parliament of England passed the New Model Army ordinance. The new English Army (there was no 'Britain' until the union with Scotland in 1707) was formed of 22,000 men, divided into 12 foot regiments of 1200 men each, 11 horse regiments of 600 men each, one dragoon regiment of 1000 men, and the artillery, consisting of 50 guns. In the United States, "Redcoat" is associated with British soldiers who fought against the colonists during the American Revolution. It does not appear to have been a contemporary expression - accounts of the time usually refer to "Regulars" or "the King's men". Abusive nicknames included "bloody backs" (in a reference to both the colour of their coats and the use of flogging as a means of punishment for military offences) and "lobsters" (most notably in Boston around the time of the Boston Massacre). It is not until the 1880s that the term "redcoat" as a common vernacular expression for the British soldier appears in literary sources, such as Kipling's poem "Tommy", indicating some degree of popular usage in Britain itself. However an isolated earlier use of this term relating to the American War of Independence appears in "The Riflemen's Song at Bennington", an old folk song that supposedly [citation needed] goes back to the 1770s.”

Someone once said that it is “better to look good than to feel good.” Another remarked that you should “always dress for success.” I wonder if the former was an officer in the English Army.

PS. This weekend I’ll be spending Saturday with Mort Kunstler at his Fredericksburg print signing and Sunday I’ll be giving my speech on Mary Ball Washington at the VAFB Women’s Convention. Hopefully I’ll have photos and a video to share next week.

Newer | Latest | Older

Throughout the history of warfare musicians have always played an important role on the battlefield. Military music has served many purposes including marching-cadences, bugle-calls and funeral dirges. Fifes, bagpipes and trumpets are just some of the tools that were used to instruct friend and intimidate foe.

Throughout the history of warfare musicians have always played an important role on the battlefield. Military music has served many purposes including marching-cadences, bugle-calls and funeral dirges. Fifes, bagpipes and trumpets are just some of the tools that were used to instruct friend and intimidate foe.

This weekend I had a great time visiting with my friend Mort Kunstler (

This weekend I had a great time visiting with my friend Mort Kunstler (