I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he [Christ] wished anyone to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other. - Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, April 12, 1803

I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he [Christ] wished anyone to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other. - Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, April 12, 1803

Without a doubt, one of the most complex aspects of Thomas Jefferson’s life story is the subject of spirituality. From his authoring of the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom and Jefferson Bible, to the many letters that he sent to friends and associates touting the teachings of Jesus Christ, Jefferson’s religious beliefs remain a perplexing riddle to this very day.

As a practicing Christian and historian, I have spent a great deal of time examining this subject and my dream of penning that best-seller revolves around a book that presents Jefferson’s experiences here in Fredericksburg when he agreed to draft the official document that separated church and state. A recurring interest, Jefferson’s attitudes on faith were the focus of the inaugural essay that I wrote for The Jefferson Project, as well as the initial debate that I participated in at Jefferson Today.

Below is a portion of my rebuttal from Jefferson Today. You can also read my essay, titled Jefferson’s Religious Freedom, over at The Jefferson Project. Plans are to open this subject up for discussion in a future posting, while providing additional insights and sources from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

CHRISTIAN CONSCIENCE?

Jefferson rejected the “divinity” of Jesus, but he believed that Christ was a deeply interesting and profoundly important moral or ethical teacher. He also subscribed to the belief that it was in Christ’s moral and ethical teachings that a civilized society should be conducted. Cynical of the miracle accounts in the New Testament, Jefferson was convinced that the authentic words of Jesus had been contaminated. His theory was that the earliest Christians, eager to make their religion appealing to the pagans, had obscured the words of Jesus with the philosophy of the ancient Greeks and the teachings of Plato. These so-called “Platonists” had thoroughly muddled Jesus’ original message. Firmly believing that reason could be added in place of what he considered to be “supernatural” embellishments, Jefferson worked tirelessly to compose a shortened version of the Gospels titled “The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth.” The subtitle stated that the work was “extracted from the account of his life and the doctrines as given by Matthew, Mark, Luke & John.”

On April 21, 1803, Jefferson sent a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush, who was a fellow ‘Founding Father’ and devout Christian, explaining his own interpretation of scripture.

Dear Sir,

In some of the delightful conversations with you in the evenings of 1798-99, and which served as an anodyne to the afflictions of the crisis through which our country was then laboring, the Christian religion was sometimes our topic; and I then promised you that one day or other I would give you my views of it. They are the result of a life of inquiry and reflection, and very different from that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed, but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished anyone to be: sincerely attached to his doctrines in preference to all others, ascribing to himself every human excellence, and believing he never claimed any other. At the short interval since these conversations, when I could justifiably abstract my mind from public affairs, the subject has been under my contemplation. But the more I considered it, the more it expanded beyond the measure of either my time or information. In the moment of my late departure from Monticello, I received from Dr. Priestley his little treatise of “Socrates and Jesus Compared.” This being a section of the general view I had taken of the field, it became a subject of reflection while on the road and unoccupied otherwise. The result was, to arrange in my mind a syllabus or outline of such an estimate of the comparative merits of Christianity as I wished to see executed by someone of more leisure and information for the task than myself. This I now send you as the only discharge of my promise I can probably ever execute. And in confiding it to you, I know it will not be exposed to the malignant perversions of those who make every word from me a text for new misrepresentations and calumnies. I am moreover averse to the communication of my religious tenets to the public, because it would countenance the presumption of those who have endeavored to draw them before that tribunal, and to seduce public opinion to erect itself into that inquisition over the rights of conscience which the laws have so justly proscribed. It behooves every man who values liberty of conscience for himself, to resist invasions of it in the case of others; or their case may, by change of circumstances, become his own. It behooves him, too, in his own case, to give no example of concession, betraying the common right of independent opinion, by answering questions of faith which the laws have left between God and himself. Accept my affectionate salutations.

- Th: Jefferson

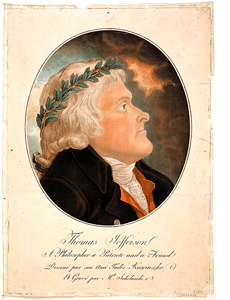

IMAGE: Thomas Jefferson, aquatint by Tadeusz Koo Ciuszko

Updated: Monday, 8 March 2010 12:14 AM EST

Permalink | Share This Post