Misquoting the Founders is a Political Epidemic

It’s no secret that the GOP has made a routine out of misquoting the Founding Fathers in support of their political agenda. According to The Washington Post: “Republicans have used incorrect quotes to portray the founders as sympathetic to modern conservatism. Knowing that people derive hope from the words of our founding fathers, Republicans frequently use and misuse their words to garner support for their positions.” Here are just a few of these counterfeit quotations:

“Thomas Jefferson wrote that government is best that governs least.” – Senator Rand Paul (R-KY)

“Government is not reason. It is not eloquence. It is force. Like fire, it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master.” – Congressman Louie Gohmert (R-TX) claiming to quote George Washington

“As Jefferson said, the price of freedom is eternal vigilance.” – Congresswoman Virginia Foxx (R-NC)

“Our third president, Thomas Jefferson, said this, ‘Eternal vigilance is the price of freedom.’” – Congressman Marlin Stutzman (R-IN)

“President George Washington said that the right to keep and bear arms is ‘the most effectual means of preserving peace.’” – Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT)

“The democracy will cease to exist, when you take away from those who are willing to work to give to those who would not.” – Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK), claiming to be quoting Jefferson

None of these quotes were said by their attributers yet the Republicans continue to misquote them again and again. Personally, I don’t know what is more embarrassing for these folks, getting tangled in their own misquotes or regurgitating piss-poor research contributions from their staff. Either way, we are on to them. Edward Lengel, a UVA professor who edited George Washington’s personal papers spoke on the irony of this practice. According to him this is the exact type of political propaganda that would have infuriated the Founders: “It’s a betrayal of Washington’s legacy. It’s a betrayal of who he was. He would have been outraged to find people manipulating his words, or making things up, to indicate that he supposedly believed this or that thing.”

I will add that it is also a betrayal of the American voter.

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 9:52 AM EST

Updated: Wednesday, 28 December 2011 7:39 AM EST

Permalink |

Share This Post

Exploring the Sexuality of a Founding Father: Gay history in the classroom and how it may reshape how we think about our past

Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens statue in Lafayette Park in Philadelphia

Pennsylvania, named one of "The Queerest Historical Sites."

In July of 2011, California became the first state to require that public school textbooks include the accomplishments of gay, lesbian and transgender Americans. Known as SB48, the measure won final passage from the state legislature when it passed on a 49-25 party-line vote, with Democrats in favor and Republicans opposed. According to LGBT Weekly, "The Fair, Accurate, Inclusive and Respectful (FAIR) Education Act amends the Education Code to finally include the contributions of LGBT people in social sciences instruction. The bill also prohibits the state Board of Education from adopting discriminatory instruction and discriminatory materials."

After signing the mandate into law Governor Jerry Brown released the following statement: "This bill revises existing laws that prohibit discrimination in education and ensures that the important contributions of Americans from all backgrounds and walks of life are included in our history books. It represents an important step forward for our state."

This historic step toward educational diversity came about as part of a liberal movement to broaden the content of history lessons taught in American classrooms. Throughout the nineties, historians and educators alike cited the need for more-inclusive lesson plans that would enable a broader demographic of students to relate to the material. This included the integration of noteworthy contributions from disabled Americans, as well as Hispanics and Pacific Islanders. Much like the civil-rights-based movement of the sixties, which incorporated more female and African American history in textbooks, this movement set out to remedy decades of neglect. One of the last groups to be addressed in American history textbooks is the gay community.

As the California ruling has opened the door for other U.S. states to revise their own curriculums to include the contributions of a broader sexual orientation, it also gives modern educators the opportunity to reexamine existing history in a different light. For over a century questions surrounding the sexuality of several American icons, including presidents James Buchanan and Abraham Lincoln, have been considered offensive and unmentionable. Today they could be the basis for a renewed interpretation. In fact, these studies could enable us to see things in a different perspective even though many of the questions raised have been quietly discussed for generations.

For fifteen years prior to his presidency, James Buchanan lived with his close friend and confidant, Alabama Senator William Rufus King, who later became vice president under Franklin Pierce. Their extremely close relationship ignited rumors around Washington D.C., prompting the ever-uncouth Andrew Jackson to refer to King as "Miss Nancy," while Aaron Brown spoke of the two gentlemen as "Buchanan and wife." The theory that one of America's most revered presidents, Abraham Lincoln was a homosexual is a more modern one. It is based on several circumstantial events and an explicit poem written by a teenage Lincoln that is open to interpretation. Gay activist C. A. Tripp has published multiple commentaries on the subject, stating that Lincoln's distant and difficult relationships with women stood in stark contrast to the warm relations that he shared with a number of men. Many Lincoln scholars vehemently refute this theory and the debate remains ongoing.

Perhaps no other American icon has had more speculation raised (and ignored) as to his sexual preference than Alexander Hamilton. This controversial Founding Father left behind an abundance of questions after dying a premature death following an ill-fated duel with political rival Aaron Burr. His is a story that begs for reexamination and it is one that may eventually necessitate revision for a whole new generation of Americans. Of course all historical analysis is subject to speculation, but what we have come to learn about the life and writings of Alexander Hamilton has revealed an interesting argument for his homosexuality.

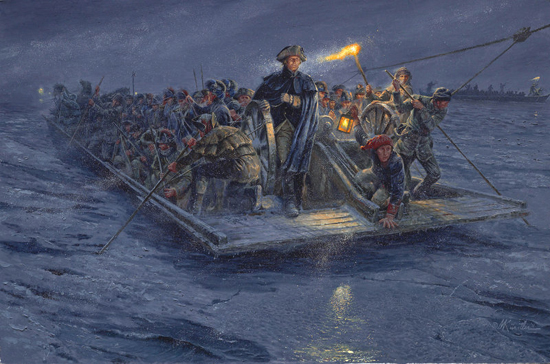

As was quite common for men of his social stature, Hamilton was a complex man of many talents. Soldier, economist, political philosopher, constitutional lawyer, secretary of the Treasury, leader of the Federalist Party and founder of the U.S. Mint were just a few of the titles he held. Hamilton's climb toward political popularity was forged during his exquisite service during the American Revolutionary War. Initially acting as an artillery officer, he later became the senior aide-de-camp to General George Washington. Hamilton again served his commander-and-chief in 1794 during the "Whiskey Rebellion" tax-revolt, acting as the president's closest military confidant. Three years later, he was unanimously named as Washington's successor and commander of a new American army, mobilizing in preparation for a potential war with France. Fortunately, the need for such a force was negated thanks to the stubborn diplomacy of President John Adams.

It was while serving on Washington's staff that Hamilton met John Laurens, the man whose relationship with him has become the subject of much inquiry. Laurens was a successful soldier and statesman from South Carolina who gained approval by the Continental Congress in 1779 to recruit a regiment of 3,000 slaves by promising them freedom in return for fighting. Despite being married to Martha Manning, Laurens arrived in the colonies as a bachelor after leaving his wife behind in London. He joined the Continental Army and following the Battle of Brandywine, was made an aide-de-camp to General Washington with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He also served with the Baron von Steuben (another rumored homosexual), doing reconnaissance at the outset of the Battle of Monmouth.

While on campaign Laurens became close friends with his fellow aides, the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton. His relationship with the latter would become one of question as to whether the two shared a homosexual, or at least a homosocial relationship, unbeknownst to their peers. Adding to the complexity of their bond is Hamilton's reputation as an adulterer. In 1791 he admitted participating in a scandalous affair with the wife of James Reynolds. In an effort to limit the political ramifications of his actions, Hamilton published a full confession of his affair, shocking both his family and supporters by not merely admitting his guilt, but also by inexplicably narrating the affair at an unexpected level of detail. The public's reaction damaged Hamilton's standing for the rest of his life. That event however took place years after the untimely death of John Laurens in 1782.

As one who specializes in human sexuality, historian Jonathan Katz contends that the primary source in support of the Hamilton-Laurens relationship can be found in a series of intimate letters that were written shortly after Laurens left Washington's staff to return to his home state of South Carolina. His goal was to persuade the state's legislature to recruit African Americans, who were flocking to fight the Continentals as British Loyalists. Despite having no military reason, both men maintained their working relationship through correspondence.

Hamilton's first letter to Laurens was penned in April of 1779 and appears to be filled with innuendo:

Cold in my professions - warm in my friendships - I wish, my Dear Laurens, it were in my power, by actions rather than words, to convince you that I love you. I shall only tell you that ‘till you bade us Adieu, I hardly knew the value you had taught my heart to set upon you. Indeed, my friend, it was not well done. You know the opinion I entertain of mankind, and how much it is my desire to preserve myself free from particular attachments, and to keep my happiness independent of the caprice of others. You should not have taken advantage of my sensibility, to steal into my affections without my consent. But as you have done it, and as we are generally indulgent to those we love, I shall not scruple to pardon the fraud you have committed, on one condition; that for my sake, if not for your own, you will always continue to merit the partiality, which you have so artfully instilled into me. . . .

And Now my Dear as we are upon the subject of wife, I empower and command you to get me one in Carolina. Such a wife as I want will, I know, be difficult to be found, but if you succeed, it will be the stronger proof of your zeal and dexterity. . . .

If you should not readily meet with a lady that you think answers my description you can only advertise in the public papers and doubtless you will hear of many . . . who will be glad to become candidates for such a prize as I am. To excite their emulation, it will be necessary for you to give an account of the lover - his size, make, quality of mind and body, achievements, expectations, fortune, &c. In drawing my picture, you will no doubt be civil to your friend; mind you do justice to the length of my nose and don't forget, that I [about five words here have been mutilated in the manuscript - some scholars theorize that Hamilton was referring to his ‘manhood'].

After reviewing what I have written, I am ready to ask myself what could have put it into my head to hazard this Jeu de follie. Do I want a wife? No - I have plagues enough without desiring to add to the number that greatest of all; and if I were silly enough to do it, I should take care how I employ a proxy. Did I mean to show my wit? If I did, I am sure I have missed my aim. Did I only intend to [frisk]? In this I have succeeded, but I have done more. I have gratified my feelings, by lengthening out the only kind of intercourse now in my power with my friend. Adieu

Yours.

A Hamilton

On September 11, 1779, Hamilton wrote a second letter in which he referred to himself as a jealous lover:

I acknowledge but one letter from you, since you left us, of the 14th of July which just arrived in time to appease a violent conflict between my friendship and my pride. I have written you five or six letters since you left Philadelphia and I should have written you more had you made proper return. But like a jealous lover, when I thought you slighted my caresses, my affection was alarmed and my vanity piqued. I had almost resolved to lavish no more of them upon you and to reject you as an inconstant and an ungrateful -. But you have now disarmed my resentment and by a single mark of attention made up the quarrel. You must at least allow me a large stock of good nature. . . .

Have you not heard that I am on the point of becoming a benedict? I confess my sins. I am guilty. Next fall completes my doom. I give up my liberty to Miss Schuyler. She is a good hearted girl who I am sure will never play the termagant; though not a genius she has good sense enough to be agreeable, and though not a beauty, she has fine black eyes - is rather handsome and has every other requisite of the exterior to make a lover happy. And believe me, I am lover in earnest, though I do not speak of the perfections of my Mistress in the enthusiasm of Chivalry.

Is it true that you are confined to Pennsylvania? Cannot you pay us a visit? If you can, hasten to give us a pleasure which we shall relish with the sensibility of the sincerest friendship.

Adieu God bless you. . . .

A Hamilton

The lads all sympathize with you and send you the assurances of their love.

One year later on September 16, 1780, Hamilton penned a third correspondence to Laurens that appears to put his affections for the recipient to be above those for his current female mistress:

That you can speak only of your private affairs shall be no excuse for your not writing frequently. Remember that you write to your friends, and that friends have the same interests, pains, pleasures, sympathies; and that all men love egotism.

In spite of Schylers black eyes, I have still a part for the public and another for you; so your impatience to have me married is misplaced; a strange cure by the way, as if after matrimony I was to be less devoted that I am now. Let me tell you, that I intend to restore the empire of Hymen and that Cupid is to be his prime Minister. I wish you were at liberty to transgress the bounds of Pennsylvania. I would invite you after the fall to Albany to be witness to the final consummation. My Mistress is a good girl, and already loves you because I have told her you are a clever fellow and my friend; but mind, she loves you a l'americaine not a la françoise.

Adieu, be happy, and let friendship between us be more than a name.

A Hamilton

The General & all the lads send you their love.

There are no other Hamilton-Laurens letters in known existence that are open to this kind of interpretation. Their relationship from here on was relatively short-lived. Two years later Laurens was killed during a skirmish, prompting a distraught and grieving Hamilton to state; "I feel the deepest affliction at the news we have just received of the loss of our dear and inestimable friend Laurens. His career of virtue is at an end.... I feel the loss of a friend I truly and most tenderly loved, and one of a very small number."

Some historians have theorized that these letters clearly present a homosocial, possibly as the result of a suppressed homosexual relationship that existed between both men while they were serving in the Continental Army. There are no eyewitness accounts that support this theory, but the above letters do leave the possibility open to question. All three letters are seldom quoted separately and they are often the subject for great debate. In an essay titled The Hamilton-Laurens Relationship Bob Arneback argues that although these letters prove nothing; "In the extant letters, this is the last of Hamilton's homoerotic bravado with Laurens. But it is quite enough to allow us to label Hamilton as a man with a wide appetite for pleasures that comfortably included homosexuality."

Jonathan Katz's pioneering book Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A., examines the relationship between Hamilton and Laurens through the understanding of same-sex love and sexual relationships as being historically contingent. He places the letters in the social context of their time without excusing their language as merely a convention or describing them in terms of brotherhood or idealized friendship. Katz then boldly theorizes that the sexual innuendo in these letters is "one of the semi-secret languages used by early American homosexuals to speak of those same-sex relations otherwise unnamable among Christians." Hamilton was an active orthodox and conventional Presbyterian-evangelical, adding yet another layer of complexity to this theory. Katz also claims that Hamilton may have had relations with Pierre L'Enfant, the French-born architect and civil engineer best known for designing the layout of the streets of Washington, D.C..

Despite these accusations there is distinct proof that Hamilton enjoyed the company and relations of women. In addition to his affair with Maria Reynolds, he later wed a woman named Elizabeth Schuyler and fathered eight children with her. She survived Hamilton for fifty years, until 1854. Eliza spent much of her life working to help widows and orphans. After Hamilton's death, she co-founded New York's first private orphanage, the New York Orphan Asylum Society. Most historians who do ascribe to the gay Hamilton theory tend to believe that Elizabeth was completely unaware of any homosexual tendencies of her husband.

Hamilton joined his friend John Laurens in the great beyond on July 12, 1804. Both a celebrated war hero and detested politician, he left behind a legacy that continues to divide critics to this very day. From his dissenting posture as an ardent Federalist to his disruptions as a member of John Adam's cabinet, Hamilton does not enjoy the same blanket-adoration as his contemporaries. Perhaps this is why questions surrounding his controversial lifestyle have gone unanswered. Ironically, as an underhanded, adulterous and potentially bi-sexual politician whose career was mired in suspicion, Hamilton appears to be more at home in today's political arena than that of his own time.

We may never know for sure if he had true homosexual affections for John Laurens or Pierre L'Enfant, but the ‘evidence' we do have is certainly open to speculation. It begs further examination or, at the least, an acknowledgement of possibility and therein lies the dilemma with this type of armchair historical analysis. It all comes down to opinion. To some, the words penned in those letters by Hamilton are simply those of a man who is dramatically stating his affections for a brother-in-arms. Others read it as a clear declaration of one man's love for another.

The Hamilton-Laurens bond has been forever captured in a sculpture that stands in Lafayette Park in Philadelphia Pennsylvania. According to The Queerest Places: A Guide to Gay and Lesbian Historic Sites: "Lafayette Park also features statues of several prominent figures of the American Revolution, whom we now claim as gay. There is a statue of Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens, who were inseparable in life and whose hands in the statue appear to be lightly touching. The two were colonels in the Continental Army and together served as interpreters for Baron von Steuben, the Revolutionary War hero and lover of men..." One look at the curious posing of the monument certainly adds to the mystique surrounding the nature of their relationship.

Some organizations have implicitly accepted the premise of the Hamilton-Laurens relationship and used it as an example of gay historical icons in support of their cause. The Alexander Hamilton American Legion Post 448 in San Francisco is the only branch of the American Legion comprised primarily of gay, lesbian, bi-sexual and transgender individuals. Since 1985, members of Post 448 have marched in both the city's Gay Pride and Veterans Day parades and served as the Color Guard unit for the Gay Games. According to their website, "The members of Alexander Hamilton Post 448 are dedicated to the welfare of GLBT veterans and current service personnel and strongly advocate the repeal of the military's ‘Don't Ask, Don't Tell' policy."

Beyond the obvious inclusion factor, how does SB48 really affect the study of history?

With a more diverse interpretation in the classroom, students could invariably look to an Alexander Hamilton as an example of a rumored homosexual whose contributions to American history are worthy of our attention. Other historical figures whose sexual preferences have been questionable could follow. The impact on how history is viewed in American classrooms as a whole could be forever changed by the broadening of its focus, just as it was in the sixties.

At the same time, reexamining our past with unsuppressed "gaydar" could also have the reverse affect as it is the very perceptions from the gay community that could in turn, counter these claims. Dr. Jeffrey Wesolowski, a student of queer-history from Ann Arbor Michigan offers some insight into how the question over what is "straight versus gay" could invariably result in a misreading of one man's affections for another. He states:

"Is the modern approach to sexuality (i.e. what we consider a gay lifestyle) similar to the conception before let's say 1900? Many scholars of gay history might say no. For example, a man might be expected to, and even wish to marry a woman, despite the fact that he was sexually attracted to men. The concept of gay marriage would have made about as much sense to such a person in such an era as flying to the moon. This internal conflict makes things more complicated with written euphemisms and relationships as such. As an American culture, we have always been rather homosocial. Endearing writings from one man to another in the 18/19th centuries were not uncommon confounding the issue further. The challenge over determining who was straight and who was gay is a perplexing one. Certainly there were many queer people of historical note and perhaps now that gay history is merging with the mainstream these questions can be more open for discussion."

Only time will tell what kind of impact the FAIR Education Act will have in the classroom, or if any of the nation's historical figures such as Alexander Hamilton will be perceived in a different way. Will Grant, a teacher at The Atheanian School in San Francisco, summarized the impact of adding gay history into curriculum. During an interview for NPR he said, "People act as if gays and lesbians popped into the historical world in 1969, and when people find out that gays and lesbians have been a part of all cultures, going past recorded history, then that really shifts the way that people think about things."

And perhaps it's that simple. Whether examining American history through a straight or gay lens, a more honest and diversified way of thinking certainly benefits us all.

Sources:

California Brings Gay History into the Classroom, Ana Tintocalis (National Public Radio, July 22, 2011)

Excerpts from My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries, ed. Rictor Norton (1998)

Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. , Jonathan Katz (Harper & Row, 1985)

John Laurens and the American Revolution, Gregory D. Massey (University of South Carolina Press, 2000)

The Federalist Papers, No. 85: Concluding Remarks, Alexander Hamilton (Independent Journal, 1788)

The Hamilton-Laurens Relationship, Bob Arnebeck, (http://bobarnebeck.com/hamlau.html)

The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, Allan McLane Hamilton (London: Duckworth, 1910)

The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett, assoc. ed. Jacob E. Cooke (NYCU, 1961)

The Queerest Places, (http://queerestplaces.wordpress.com/2009/01/13/lafayette-park/)

The Works of Alexander Hamilton, ed. John C. Hamilton (New York, 1851)

Why Alexander Hamilton?, American Legion Post 448, (http://www.post448.org/why.htm)

How do other country's teach the Revolution?

Two recent Op-Eds posted here on ‘Blog, or Die.’ dealt with what I consider to be fraudulent practices of teaching the American Revolution. The first took elementary academia to task for propagating the watered down and candy-coated version of American history that we are taught as children. The second took proponents of American-Exceptionalism to task for disseminating the woefully naïve and inflated American propaganda that we have come to expect at Tea Party conventions.

Two recent Op-Eds posted here on ‘Blog, or Die.’ dealt with what I consider to be fraudulent practices of teaching the American Revolution. The first took elementary academia to task for propagating the watered down and candy-coated version of American history that we are taught as children. The second took proponents of American-Exceptionalism to task for disseminating the woefully naïve and inflated American propaganda that we have come to expect at Tea Party conventions.

Both are full of agenda-driven biases and do little to aid in the understanding of our country’s history. They also reveal an antiquated perspective and sense of insecurity. (But if re-telling the same stories and wearing a big foam finger that says “We’re #1” is what helps some folks sleep at night, who am I to judge?)

Today I thought it might be interesting to see how the ‘other side’ teaches the American Revolution. The following excerpts are taken from online surveys presented to students and graduates from Canada and the United Kingdom. Some folks may be surprised to know that the American Revolution isn’t really on the radar of other countries, even the ones who participated in it.

BRITIAN: “It’s called the American War of Independence, and it’s one of the events that are studied as part of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the Jacobite Rebellion or the rise of the British Empire. It also crops up as part of the background to the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic Wars. To the British it was just one of the things that happen when the main event - fighting the French and forming the United Kingdom - was going down. At the time the British Empire was beginning to form and priorities were elsewhere. The Brits were fighting the Spanish, the French, various Sultans and Maharajas in India and trying to hold on to the Caribbean spice/slave trade at the time. So there was a whole lot going on. You have to realize it’s not an integral part of British history. Yes it shaped the British Empire in that it leads to a shift towards India and Africa, but for Britain it was the loss of some colonies rather than something fundamental. British history covers over 2,000 years if you start with the Romans, even in recent times two world wars that wrecked Europe and ruined the Empire were far more integral.”

IRELAND: “In my school in Northern Ireland it was mentioned in passing as precursor to the republic gaining independence. Although obviously many years apart 1776-1916 (1922). Apart from that and the famine/Irish emigration we learn very little about American history. My compulsory history at school consisted of, as far as I can remember; some monarchy, some holocaust stuff, some the women’s rights movement over here, the troubles in Ireland, and a bit on the American west, which we all agreed was a stupid choice of subject and resented for being pretty much totally disconnected from anything we wanted to learn about. I remember being pretty disdainful for most of what was on the syllabus actually now come to think of it.”

UNITED KINGDOM: “The problem for America is that as a “young” nation, it needs to nurture its own mythology to arrive at a sense of national identity. The winners almost always get to write the “definitive” version of events and the truth is often, if not always, ignored or suppressed. The American Revolution, as the birth pains of the new country, is a prime candidate for such mythology. A myth repeated for 200 years takes on the mantle of truth. They do portray the Americans as bad, but the Americans portray them as bad. Just like Germans portray the allies of WWI as bad and vice versa. Every war is portrayed differently in different countries.”

SCOTLAND: “In Scotland schools teach the wars with England and the highland clearances. Never learned much about English history until the point where we learn about the union. World War 1 and 2 are the other big topics. The American civil war, America in general and even England is not taught in History and if they did it would likely be a single lesson.”

CANADA: “We learn about it a little bit in Canada, but we focus on the British (Canadian) / French point of view. The War of 1812 is far more important to us. I’m curious why so many Americans think the War of 1812 was won by America. In Canada we are taught it was a tie. If you look at the Treaty of Ghent, all pre war borders would be reinstated, and no surrender by either side. The treaty was mainly struck because the reasons for the war no longer existed. The short of it was that Britain was at war with France (the Naploeonic War), and the U.S. was giving the French assistance. So the British put trade barriers on America. Soon America declared war, and the War of 1812 began. After the Napoleonic War ended Britain no longer needed to place trade sanctions on America. This is what led to the Treaty of Ghent.”

Counter-Response: Unalienable rights?

My last Op-Ed (below) spawned a counter-post over on the Old VA Blog. This rebuttal presents the concept of ‘unalienable rights,’ and argues that American Exceptionalism is valid because the Founding Fathers believed that our rights come from God, not Kings, nor governments, nor Congress nor the President, none of which have the moral authority to grant rights; they can only acknowledge them.

My last Op-Ed (below) spawned a counter-post over on the Old VA Blog. This rebuttal presents the concept of ‘unalienable rights,’ and argues that American Exceptionalism is valid because the Founding Fathers believed that our rights come from God, not Kings, nor governments, nor Congress nor the President, none of which have the moral authority to grant rights; they can only acknowledge them.

The phrase “that they [all men] are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” from the Declaration of Independence was used as the basis for this theory. It is an assumption that has been debated by historians and philosophers alike for generations.

Ironically, I am in the process of finishing up a brilliant study of the Declaration by Pauline Maier titled American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Among its revelations is the fact that the document was anything but visionary. According to Maier’s findings, ninety such declarations were already issued throughout the Thirteen Colonies from April to July 1776. Her book also does a wonderful job of reminding us that Declaration is a secular, man-made document - extraordinary in its own right - but not a religious dogma or scripture.

According to the counter-post I referenced above, the use of term ‘unalienable rights’ by the Founders was a deliberate choice that affirms American Exceptionalism: “It means that those rights are incapable of being surrendered or taken away - basic rights which the Founders believed [and correctly so] preexisted any government.” Remember, their argument is that God alone gave us our rights and the Founders used this as a primary point when declaring our separation from England.

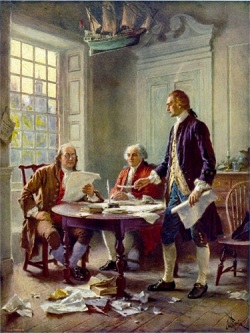

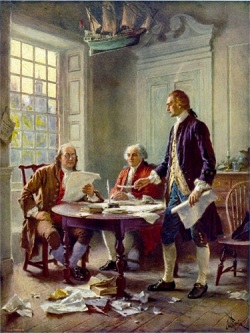

This is a fine interpretation. However, I take issue with the specific assertion that the Founding Fathers used the concept of divinized ‘rights’ as the basis for our nation’s independence. The exact phrase used was: “One item which often gets overlooked in what makes America exceptional is how the Founders viewed rights…specifically, that our rights come from God.” The truth is that the reference to “their Creator” bestowing any rights on the nation’s citizenry was not even part of the original draft. In fact, it wasn’t even inserted into the Declaration of Independence until the very end. Unfortunately the original draft of the proclamation no longer exists, but a compilation has been reconstructed from various copies that do. Here is the evolution of the phrase in question:

Jefferson’s original states: “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable, that all men are created equal and independent; that from that equal creation they derive in rights inherent and unalienables, among which are the preservation of life, and liberty and the pursuit of happiness; . . .”

In the John Adams copy, written, sometime between June 11 and June 28, in his own (J. Adams) handwriting we have the following: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal and independent; that from that equal creation they derive in rights inherent and unalienables, among which are the preservation of life, and liberty and the pursuit of happiness; . . .”

Before being submitted to Congress, the above section was changed to the following: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. . . .”

Note the underlined addition of the phrase “endowed by their Creator”. Though many other changes were made in the rest of the document, Congress accepted those lines for the finished Declaration.

So…the question remains, does this statement support American Exceptionalism? I say no. First off, this entire concept was anything but a uniquely “American ideal.” The 17th-century English, philosopher John Locke and the Irish philosopher Francis Hutcheson both presented the theory of natural law and unalienable rights prior to the Founders. Second, and perhaps most telling of all, is the fact that the Founders themselves were not unanimous in support of this theory.

Thomas Jefferson, the very author of the Declaration, added that additional verbiage only at the insistence of his fellow committee members. His friend James Madison, author of the U.S. Constitution, believed that there were social rights, arising neither from natural law nor from positive law (which are the basis of natural and legal rights respectively) but from the social contract from which a government derives its authority.

In other words Madison believed that society endows these rights upon themselves in order to maintain a civilized and prosperous culture. This power comes for The People, by The People. That’s not at all a divine intervention which was the entire basis for the pro-AE crowd’s counterpoint. So although I agree with the premise that the Declaration of Independence is an exceptional document, I do not believe that its language alone affirms American Exceptionalism.

We often forget the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, where the Founders gathered in Philadelphia to argue and debate about what rights and responsibilities should be included in the constitution. After three years of heavy argument, negotiation, compromise and salesmanship, the 13 states voted on the constitution, and the rights and responsibilities within it became law. This reinforces the idea that the concept of rights (regardless of origin) was an extremely complex and controversial subject, even to the men who established them.

Two recent Op-Eds posted here on ‘Blog, or Die.’ dealt with what I consider to be fraudulent practices of teaching the American Revolution.

Two recent Op-Eds posted here on ‘Blog, or Die.’ dealt with what I consider to be fraudulent practices of teaching the American Revolution.  My last

My last