Troy Davis and the Civil War

This week’s biggest news story was the controversial execution of Georgia Death Row inmate Troy Davis and the reignited debate over the death-penalty in America. This got me thinking about how public executions have been carried out in our country and their obvious emotional impact on those who witness it.

You may recall a few weeks ago when I mentioned formalizing my lecture for the Richmond Civil War Round Table. That talk will take place in May of next year. The RCWRT folks were very interested in my book on The Civil War in Spotsylvania: Confederate Campfires at the Crossroads, and requested that I speak on that title. Apparently someone at the RT revealed how impressed they were with my extensive use of first-hand recollections. This collection of letters makes up the majority of the book which has become both a reference source and a pleasure read. There is very little glamour or romance in this work, and I think that I met my goal of presenting the miserable and mundane life that Johnny Reb experienced while on campaign. It’s a very “gray” book (no pun intended).

One topic that they specifically mentioned anticipating is the section on camp justice. In the chapter titled “Crime and Punishment: Executions, Courts-Martial and Humiliations,” I present multiple accounts and images of soldiers being punished and killed for crimes against their fellow soldiers. Here is an excerpt:

As the war dragged on into its third and fourth years, soldiers on both sides of the conflict began to flee the army in record numbers. Some were traumatized by the horrors they had witnessed, others were shamed by the atrocities they had committed and many more were disenchanted with the inexperienced officers who ultimately hampered their chances at survival. Southern troops were more likely to desert, as their supplies were dwindling at a more rapid rate compared to their Northern counterparts who were better outfitted. According to Dr. James I. Robertson Jr. in Tenting Tonight, one in every seven Confederates would eventually desert. As the soldiers fell into a deeper sense of desperation, the futility of their fight and cause became overwhelming at times. One Rebel soldier wrote, “Many of our people at home have become so demoralized that they write to their husbands, sons, and brothers that desertion is now not dishonorable.”

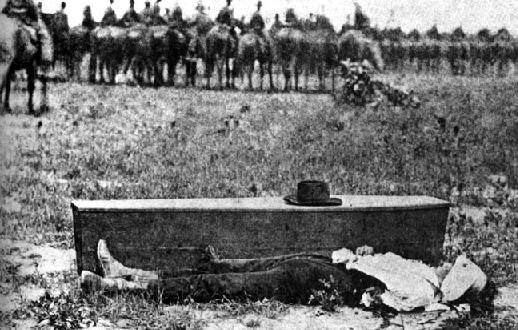

In order to curb a mass exodus from spreading throughout the ranks of the Confederate army, officers were forced to make grim examples of those who were apprehended while attempting to abandon their duty. The odds of successfully escaping were said by some to be three to one in favor of the soldier. Those who were caught, however, were dealt with in a swift and deadly manner. Following a court-martial, deserters would often be sentenced to death by firing squad. These public executions were to be carried out in front of the entire camp in an effort to strike fear in the hearts of future would-be fugitives.

Each prisoner would be given an opportunity for prayer with a camp chaplain or priest and then blindfolded and (hopefully) shot dead in the chest by a group of riflemen who usually had one loaded musket and the rest primed with powder in place of projectiles. This was done to help dispel guilt. Many times the prisoner’s body would be positioned so as to fall right into a coffin. Sometimes, the lack of marksmanship among the firing squad required additional volleys to finish the job. This made the horrific affair all the more difficult to watch, as the additional suffering of a fellow countryman was unbearable.

Less drastic punishments involved the public humiliation of wearing berating signage, being forced to do hard labor, the branding of the letter “D” for deserter or “C” for coward on the soldier’s hand or cheek or simply being drummed out of camp in a reprehensible fashion. In an age when nobility was held in the highest regard, the dishonor one would bring upon himself and his family by running away was usually deterrent enough. However, as the trauma of war destroyed one’s optimism, the risk of death and disgrace became less frightening. Some Confederate officials were concerned about the negative effect of camp executions on what remained of troop morale. Several states instituted a no-punishment clause for soldiers who willfully returned to their ranks. One governor wrote a public affirmation that stated,

“Many of you have, doubtless, remained at home after the expiration date of your furloughs, without the intention to desert the cause of your country, and you have failed to return to your Commands for fear of the penalty to which you may be subjected. Many of you have left your Commands without leave, under the mistaken notion that the highest duty required you to provide sustenance and protection to your families. Some have been prompted to leave by one motive and some by others. Very few, I am persuaded, have left with the intent to abandon the cause of the South.” He added, “I am authorized to say that ALL WHO WILL without delay VOLUNTARILY return to their Commands, will receive a lenient and merciful consideration; and that none, who so return within forty days from this date, will have the penalty of death inflicted on them.”

In a letter from Spencer Glasgow Welch, a surgeon in the 13th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry (McGowan’s Brigade), to his wife, the physician details the events of an execution by firing squad:

Camp near Rappahannock River Va

March 5, 1863

Edwin Jim Allen and Ben Strother took dinner with me yesterday and I think I gave them a pretty good dinner for camp. We had biscuit, excellent ham, fried potatoes, rice, light bread butter, stewed fruit and sugar. They ate heartily as soldiers always do. Edwin is not suffering from his wound, but on account of it he is privileged to have his baggage hauled. A man was shot near our regiment last Sunday for desertion. It was a very solemn scene. The condemned man was seated on his coffin with his hands tied across his breast. A file of twelve soldiers was brought up to within six feet of him, and at the command, a volley was fired right into his breast. He was hit by but one ball because eleven of the guns were loaded with powder only. This was done so that no man can be certain that he killed him. If he was the thought of it might always be painful to him. I have seen men marched through the camps under guard with boards on their backs, which were labeled “I am a coward,” or “I am a thief,” or “I am a shirker from battle” and I saw one man tied hand and foot astride the neck of a cannon and exposed to view for sixteen hours. These severe punishments seem necessary to preserve discipline.

Spencer Glasgow Welch

What this (and the other letters not quoted here) tells me is that even in time of war when mass brutality and murder are a daily occurrence, the execution of one’s fellow man had a definite impact on those who witnessed it. This trauma is not unlike what is being experienced today as Americans are rethinking whether or not the administration of the death sentence is still tolerable.

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 10:27 AM EDT

Updated: Friday, 23 September 2011 12:06 PM EDT

Permalink |

Share This Post

50 years later, Maris still matters

This weekend the New York Yankees organization will commemorate the 50th anniversary of Roger Maris’ historic 1961 homerun season. Even the most ardent Yankees haters (to include my friend and co-author Eric Wittenberg) have to give Roger respect for breaking one of the most difficult and coveted records in all of professional sports. The Maris family will be on hand, as well as surviving members of the 1961 Yankees squad. To commemorate this commemoration, here is an article that I penned for Baseball-Almanac a few years ago titled 61 in ‘61:

This weekend the New York Yankees organization will commemorate the 50th anniversary of Roger Maris’ historic 1961 homerun season. Even the most ardent Yankees haters (to include my friend and co-author Eric Wittenberg) have to give Roger respect for breaking one of the most difficult and coveted records in all of professional sports. The Maris family will be on hand, as well as surviving members of the 1961 Yankees squad. To commemorate this commemoration, here is an article that I penned for Baseball-Almanac a few years ago titled 61 in ‘61:

When modern baseball fans look back at all the classic record-breaking moments that they have witnessed in their lifetime, it is quite possible that one number really stands out in their mind. That number is 62. Why? Because most of them could never forget the excitement and pageantry of watching Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa [since then exposed as juicers] both set new standards in 1998, by breaking the all-time single season home run record, the most revered record in all of sports.

It was the first time, in a long time, that America’s passion for the game resembled the glory days, when it truly was our nation’s pastime and the players were larger-than-life heroes. And although their legacy has come under scrutiny due to the steroids scandal that has stained the entire era, both players were credited for giving major league baseball a much needed shot in the arm (no pun intended).

Despite the fact that another suspicious slugger named Barry Bonds [also a chemically enhanced fraud] has since set the new magic number at 73, their race seemed more romantic and brought a lot of overdue attention to the man whose record they were chasing, Roger Maris. It also seemed more fitting as they were both competing in a similar situation as Maris and his teammate Mickey Mantle had in 1961. Both contests were between two friends pushing each other to be better on and off the field; neither ever letting their competitiveness get in the way of their friendship or their friendship get in the way of their competitiveness.

The press had dubbed them “The M&M Boys” and their story is an incredible example of what impact sports can have when two teammates who are as opposite as can be, come together to create something special. To understand this, one has to look at both men individually to see what they accomplished together.

Roger Maris was a great ballplayer who never got the respect he deserved. Unfortunately, the press never really considered him “hero” material, but when you look at his life, on and off the field, you realize that he was the ideal hero. He was a good husband, father and athlete, who was more concerned with the success of his team than his own individual stats. (An attitude seldom seen in today’s game.)

No record ever hung around a player’s neck more like an albatross than Roger Maris’ 61 homers in 1961. As late as the 1980 All-Star Game he fumed, “They acted as though I was doing something wrong, poisoning the record books or something.” In surpassing Babe Ruth’s supposedly unsurpassable record, Maris faced the hostility of the baseball public on several fronts.

First, although he had been the 1960 American League MVP, he was basically a .269 hitter, still an unknown quantity unworthy of dethroning America’s greatest sports hero. That he played the game with a ferocious intensity and that he was a brilliant right fielder and an exceptional baserunner, well, that was irrelevant.

Second, for most of the season Maris wasn’t the only batter chasing the ghost of the Babe. His teammate Mickey Mantle, the successor to Ruth, to Lou Gehrig, and to Joe DiMaggio, was the people’s choice. It was Mantle who hit 500-foot home runs that thrilled fans. Mantle garnered support as the season-long chase headed toward September.

Maris? He was merely efficient; a left-handed hitter who had just the swing to take advantage of that friendly porch in Yankee Stadium’s right field. He rarely hit a homer further than 400 feet. His charisma quotient was almost nil. That 1961 season was the first year of expansion and the first year of the 162-game season. With the addition of two teams to the American League, many hitters had their greatest seasons, such as Norm Cash, who somehow hit .361, corked bat and all. Expansion also meant an expanded schedule. Ruth had set his record in 1927 in a 154-game season.

So for many people, Maris’ feat would be tainted if he needed more than 154 games to break Ruth’s record. Commissioner Ford Frick even announced that if Maris took more than 154 games to break the record it would go into the record books as a separate accomplishment from Ruth’s, with an asterisk, so to speak. “As a ballplayer, I would be delighted to do it again,” Maris once remarked. “As an individual, I doubt if I could possibly go through it again. They even asked for my autograph at mass.” As always, Maris was being honest. He once said about playing baseball for a living, “It’s a business. If I could make more money down in the zinc mines, I’d be mining zinc.” Could anyone have been more unlike the Babe?

In his first game in Yankee pinstripes, Maris singled, doubled, and smacked two home runs. His MVP numbers included a league leading 112 RBIs and 39 home runs, only one behind league-leader Mantle, although he missed 18 games with injuries. In 1961 Maris stayed healthy and played 161 games, a career high. As he and Mantle made their charge at Ruth’s home run record, the Yankees even considered switching Maris, who batted third, and Mantle, who batted fourth, to give Mantle a better shot at the record.

If the switch had been made, Maris almost certainly would not have broken the record. Consider this: Maris did not receive one intentional walk in 1961. After all, who would walk Maris to get to Mantle? While most players would have welcomed such a dilemma, Maris did not. “I never wanted all this hoopla,” he said. “All I wanted is to be a good ballplayer, hit 25 or 30 homers, drive in around a hundred runs, hit .280, and help my club win pennants. I just wanted to be one of the guys, an average player having a good season.”

Mantle fell back in the middle of September when he suffered a hip injury. Maris kept it up and went into the 154th game of the season in Baltimore with 58 homers. He gave it his best shot that night. He hit No. 59 and then hit a long foul on his second-to-last at bat. Alas, in his last at bat, against Hoyt Wilhelm, he hit a checked-swing grounder. “Maybe I’m not a great man, but I damn well want to break the record,” he said. He finally did it on the last day of the season against the Red Sox’s Tracy Stallard. Fittingly it went about 340 feet into Yankee Stadium’s right field porch. Maris also made back-to-back MVP honors, driving in a league leading 142 runs.

As expected MLB Commissioner (and The Babe’s ghostwriter), Ford C. Frick ruled that since Maris had played in a 162-game schedule (as opposed to Ruth’s 154), his record would be listed officially with a qualifying asterisk; this decision stood until 1991. Although, he never experienced the same hitting streak, his consistency as a power hitter continued and he hit 275 home runs during his 12-year career.

Maris remained bitter about the experience. He said of that season, “Do you know what I have to show for 61 home runs? Nothing. Exactly nothing.” Despite all the controversy, Maris was awarded the American League’s MVP Award for the second straight year. It is said, however, that the stress of pursuing the record was so great for Maris that his hair occasionally fell out in clumps during the season. Later Maris even surmised that it might have been better all along had he not broken the record or even threatened it at all.

Mickey Mantle, like Maris, was also an exceptional athlete from the Midwest, but with a press-friendly personality and movie-star good looks that made him a fan favorite both on and off the field. “The Mick” fit into the Yankee persona perfectly and his contributions to the pinstripes were on par with the long line of Yankee legends that had come before him. Mickey represented what America is all about: a young kid from the mid-west, going to the big city, living the American dream and becoming a sports legend. A courageous player, he achieved greatness despite an arrested case of osteomyelitis, numerous injuries and frequent surgery.

The powerful Yankee switch-hitter belted 536 homers (many of the tape-measure variety), won the American League home run and slugging titles four times, collected 2,415 hits, and batted .300 or more 10 times. The three-time MVP was named to 20 All-Star teams. He holds numerous World Series records, including most home runs (18).

Opposites yes, but also equals, both summed up their own careers perfectly. Mickey said, “It was all I lived for, to play baseball.” and Roger was quoted as saying, “All I wanted was to be a good ballplayer.”

Maris has not been elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but his teammate Mantle was elected unanimously in his first year of eligibility. Many historians credit Ford Frick’s decision to ‘footnote’ Maris’ epic achievement as having an effect on his ability to be put on the ballot. Others simply state that Maris did not have the cumulative statistics to warrant such an honor. Ironically, the decision to add the asterisk has also stained the commissioner’s legacy.

The first MLB leader not to have a political background, Ford Frick was a multi-talented journalist with experience in teaching, ghost writing and advertising. After graduating from DePauw University, Frick took a position as an English teacher at Colorado High School and also freelanced as a beat writer for the Colorado Springs Gazette. Two years later, he left teaching to become the supervisor of training in the rehabilitation division of the War Department for four states (Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming). Although the position was important, Frick could not ignore his “writer’s bug” and briefly worked for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver before returning to Colorado Springs to open his own advertising agency and write a weekly editorial column for the Colorado Springs Telegraph.

An enthusiastic baseball fan, Frick landed his dream job in 1922 after joining the sports staff of the New York American. The following year, he moved on to the Evening Journal where he covered the New York Yankees and eventually became a ghostwriter for Babe Ruth. Things got even better when he finally left the typewriter behind in favor of the microphone to become a sportscaster with station WOR. A rising figure in the sports media, Frick was named the first director of the National League Service Bureau and was put in charge of all publicity for Major League Baseball. He excelled rapidly at the position and was later elected as the President of the National League, succeeding John A. Heydler.

His first act as president was a passionate proposal for the establishment of a National Baseball Museum to honor the greatest players ever to take the field. This, of course, led to the Hall of Fame. He was also instrumental in saving several franchises from bankruptcy, including the Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, Boston Braves, Cincinnati Reds and the Pittsburgh Pirates. Immensely popular amongst the owners, he held the position until September 1951 when sixteen of them elected him commissioner on September 20, 1951.

During his tenure, Frick was responsible for many changes in the reconstruction, expansion and transition of baseball. Some of the major changes included the growth from eight to ten teams in each league; the establishment of multiple national television contracts; a league draft and college scholarship system; and the introduction of baseball on the international level in countries such as Japan, Central America, Holland, Italy and Africa.

Not unlike his Major League Baseball forefathers, Frick was contested on several occasions for policies that did not agree with the public’s view. The verdict surrounding Roger Maris’ single-season homerun record remained at the top of that list. The decision stood for the next thirty years and remained as a black eye on an otherwise stellar career. Frick was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1970. He also became the namesake of the Ford C. Frick Award, which is given to outstanding Hall of Fame broadcasters.

In 1991, then MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent officially removed the asterisk from the record. Unfortunately, Roger Maris had passed away in 1985, never receiving full credit for his unparalleled athletic accomplishment.

61 HOMERUNS BY ROGER MARIS HR | Game | Date / Box | Pitcher | Team | Throws | Where | Inning |

| 1 | 11 | 04-26-1961 | Paul Foytack | Detroit | Right | Away | 5th |

| 2 | 17 | 05-03-1961 | Pedro Ramos | Minnesota | Right | Away | 7th |

| 3 | 20 | 05-06-1961 | Eli Grba | Los Angeles | Right | Away | 5th |

| 4 | 29 | 05-17-1961 | Pete Burnside | Washington | Left | Home | 8th |

| 5 | 30 | 05-19-1961 | Jim Perry | Cleveland | Right | Away | 1st |

| 6 | 31 | 05-20-1961 | Gary Bell | Cleveland | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 7 | 32 | 05-21-1961 | Chuck Estrada | Baltimore | Right | Home | 1st |

| 8 | 35 | 05-24-1961 | Gene Conley | Boston | Right | Home | 4th |

| 9 | 38 | 05-28-1961 | Cal McLish | Chicago | Right | Home | 2nd |

| 10 | 40 | 05-30-1961 | Gene Conley | Boston | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 11 | 40 | 05-30-1961 | Mike Fornieles | Boston | Right | Away | 8th |

| 12 | 41 | 05-31-1961 | Billy Muffett | Boston | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 13 | 43 | 06-02-1961 | Cal McLish | Chicago | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 14 | 44 | 06-03-1961 | Bob Shaw | Chicago | Right | Away | 8th |

| 15 | 45 | 06-04-1961 | Russ Kemmerer | Chicago | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 16 | 48 | 06-06-1961 | Ed Palmquist | Minnesota | Right | Home | 6th |

| 17 | 49 | 06-07-1961 | Pedro Ramos | Minnesota | Right | Home | 3rd |

| 18 | 52 | 06-09-1961 | Ray Herbert | Kansas City | Right | Home | 7th |

| 19 | 55 | 06-11-1961 | Eli Grba | Los Angeles | Right | Home | 3rd |

| 20 | 55 | 06-11-1961 | Johnny James | Los Angeles | Right | Home | 7th |

| 21 | 57 | 06-13-1961 | Jim Perry | Cleveland | Right | Away | 6th |

| 22 | 58 | 06-14-1961 | Gary Bell | Cleveland | Right | Away | 4th |

| 23 | 61 | 06-17-1961 | Don Mossi | Detroit | Left | Away | 4th |

| 24 | 62 | 06-18-1961 | Jerry Casale | Detroit | Right | Away | 8th |

| 25 | 63 | 06-19-1961 | Jim Archer | Kansas City | Left | Away | 9th |

| 26 | 64 | 06-20-1961 | Joe Nuxhall | Kansas City | Left | Away | 1st |

| 27 | 66 | 06-22-1961 | Norm Bass | Kansas City | Right | Away | 2nd |

| 28 | 74 | 07-01-1961 | Dave Sisler | Washington | Right | Home | 9th |

| 29 | 75 | 07-02-1961 | Pete Burnside | Washington | Left | Home | 3rd |

| 30 | 75 | 07-02-1961 | Johnny Klippstein | Washington | Right | Home | 7th |

| 31 | 77 | 07-04-1961 | Frank Lary | Detroit | Right | Home | 8th |

| 32 | 78 | 07-05-1961 | Frank Funk | Cleveland | Right | Home | 7th |

| 33 | 82 | 07-09-1961 | Bill Monbouquette | Boston | Right | Home | 7th |

| 34 | 84 | 07-13-1961 | Early Wynn | Chicago | Right | Away | 1st |

| 35 | 86 | 07-15-1961 | Ray Herbert | Chicago | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 36 | 92 | 07-21-1961 | Bill Monbouquette | Boston | Right | Away | 1st |

| 37 | 95 | 07-25-1961 | Frank Baumann | Chicago | Left | Home | 4th |

| 38 | 95 | 07-25-1961 | Don Larsen | Chicago | Right | Home | 8th |

| 39 | 96 | 07-25-1961 | Russ Kemmerer | Chicago | Right | Home | 4th |

| 40 | 96 | 07-25-1961 | Warren Hacker | Chicago | Right | Home | 6th |

| 41 | 106 | 08-04-1961 | Camilo Pascual | Minnesota | Right | Home | 1st |

| 42 | 114 | 08-11-1961 | Pete Burnside | Washington | Left | Away | 5th |

| 43 | 115 | 08-12-1961 | Dick Donovan | Washington | Right | Away | 4th |

| 44 | 116 | 08-13-1961 | Bennie Daniels | Washington | Right | Away | 4th |

| 45 | 117 | 08-13-1961 | Marty Kutyna | Washington | Right | Away | 1st |

| 46 | 118 | 08-15-1961 | Juan Pizarro | Chicago | Left | Home | 4th |

| 47 | 119 | 08-16-1961 | Billy Pierce | Chicago | Left | Home | 1st |

| 48 | 119 | 08-16-1961 | Billy Pierce | Chicago | Left | Home | 3rd |

| 49 | 124 | 08-20-1961 | Jim Perry | Cleveland | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 50 | 125 | 08-22-1961 | Ken McBride | Los Angeles | Right | Away | 6th |

| 51 | 129 | 08-26-1961 | Jerry Walker | Kansas City | Right | Away | 6th |

| 52 | 135 | 09-02-1961 | Frank Lary | Detroit | Right | Home | 6th |

| 53 | 135 | 09-02-1961 | Hank Aguirre | Detroit | Left | Home | 8th |

| 54 | 140 | 09-06-1961 | Tom Cheney | Washington | Right | Home | 4th |

| 55 | 141 | 09-07-1961 | Dick Stigman | Cleveland | Left | Home | 3rd |

| 56 | 143 | 09-09-1961 | Mudcat Grant | Cleveland | Right | Home | 7th |

| 57 | 151 | 09-16-1961 | Frank Lary | Detroit | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 58 | 152 | 09-17-1961 | Terry Fox | Detroit | Right | Away | 12th |

| 59 | 155 | 09-20-1961 | Milt Pappas | Baltimore | Right | Away | 3rd |

| 60 | 159 | 09-26-1961 | Jack Fisher | Baltimore | Right | Home | 3rd |

| 61 | 163 | 10-01-1961 | Tracy Stallard | Boston | Right | Home | 4th |

Data courtesy of Baseball-Almanac.com

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 9:34 PM EDT

Updated: Thursday, 22 September 2011 8:46 AM EDT

Permalink |

Share This Post

Remembering Richard

Next week marks the 148th anniversary of the Battle of Chickamauga, fought September 19–20, 1863. It also marks the last week that Richard Kirkland walked on the earth. In acknowledgement of his death I am posting the original lecture that served as the base narrative for our documentary film "The Angel of Marye's Heights." On Wednesday, May 28th, 2008 I had the honor and privilege of giving this talk to the Fredericksburg Civil War Roundtable at the Jepson Alumni Center at Mary Washington University. The FCWRT is one of the oldest in the country and was founded in 1952. The overall theme of my presentation was the life, death, and legacy of Confederate Infantry Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland of the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers. My focus went beyond this extraordinary soldier's life story to show how the memory of his humanitarian act here at Fredericksburg became so important to the country when commemorating the war in later years. The transcript of my lecture follows:

Thank you Jim. Good evening folks. It is certainly an honor and a privilege to have the opportunity to speak to you tonight. When Mr. Ford contacted me, he initially requested a presentation on 'Stonewall' Jackson. However, when I heard that the theme of this year was "Great Lives that Touched Fredericksburg during the Civil War," there was perhaps no greater choice of topic in my opinion than that of Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland. Like many of you, I have been a longtime admirer of the story of the “Angel of Marye's Heights” and this presentation forced me to further research what is truly an extraordinary life.

It was no surprise that I was able to retrieve some great sources for this evening's talk. Mac Wycoff of the National Park Service has done a wonderful job compiling and publishing information on Sgt. Kirkland. I was able to find a variety of materials in the bound volumes at Chatham, as well as in a short biography written by a novice historian named Les Carroll. I was also able to get transcripts of Kirkland's personal letters from Susan Sweet of the Orange County Round Table out in California. Although I had previously published an essay on Kirkland, as well as a chapter in my devotional titled "The Southern Samaritan," I still believe that I have just begun to scratch the surface of this remarkable man's story, which has inevitably touched me.

So let's begin this evening with a couple simple questions: What is so special about this man and the act of humanity that he exhibited amidst the madness of war? And how did a young man from South Carolina leave such an indelible mark not only on Fredericksburg, Virginia, but ultimately on the rest of the country? Well for one, Kirkland's legacy is based first and foremost on a true story. It is an inspirational story. It is an uplifting story. Even in some respects it is an unbelievable story. But it is both amazing, and true.

Now I'll be the first to admit that much of our Civil War history is far too often mired in folklore and myth. We historians are guilty at times of romanticizing things that should not be romanticized and idolizing people who shouldn't be idolized. Yet this single incident that occurred here in Fredericksburg is revered because it is as profound and inspirational as it sounds. It is one of those rare instances when reality reads like a Hollywood script and remains reality.

I was amazed while browsing through the NPS archives by the number of accounts from eyewitnesses that repeatedly corroborate the story of the “Angel of Marye's Heights.” Time and time again, memoirs repeated the same story over and over. So it leaves little doubt in my mind. We are NOT propagating a legend. However, we must also acknowledge that the telling of this tale has been embellished, includes speculation, and has been marketed over and over in a variety of capacities through the years. Tonight I will show both sides.

While researching Kirkland's history I was fascinated with the monumental efforts that were put forth during the Civil War Centennial to commemorate the event by everyone from the Confederate Veteran's Association to the U.S. House of Representatives. I will be quoting a number of those sources, along with excerpts from my own book and memoirs from those who knew the man himself. Ultimately there is perhaps no other single event here in Fredericksburg that has captured the hearts and minds of both citizens and soldiers like this one. It is after all, the largest marker on the field near the stone wall and therefore the Kirkland Monument is essentially the identifying 'universal' symbol of the battlefield. Additionally, the 'character' of Sgt. Kirkland has become a historical 'pop-icon' of sorts as the likeness of his deed has become forever frozen through the marketing of statues, figurines, paintings and toys. These are just a few of the items I was able to find. In essence, he has become a souvenir, maybe even a brand... a 19th-century "Good Samaritan" if you will.

Of course Kirkland has also been cast in sculpture. One adorns the field here in Fredericksburg, while another sits in the courtyard at the National Civil War Museum up in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. I think that speak volumes. Of all the significant subjects to choose from, the country's national museum selected this event and this likeness for their site too. Honestly, I can't think of any other action by an enlisted man during the Civil War that has been more celebrated than this one. So it is with that premise that I present to you tonight the life, death, and legacy of Sgt. Kirkland. It is my hope that you will leave here with a greater appreciation not only for an act of charity that momentarily stopped the war, but for the entire life of the man who was more than just the 'Angel of Marye's Heights.'

Richard Rowland Kirkland was born in August of 1843 in the rural county of Kershaw in South Carolina. He was a typical farm boy whose family had strong ties to the community and a long lineage of military service. It is said that at least 10 of his ancestors had fought in the Revolutionary War. His great-grandfather, Daniel Kirkland, had served as a supply officer in the army and had fought in the Battle of Camden, S.C. in 1780.

It seems the very soil that his family farmed was hallowed by the service of his forefathers. To quote a UDC study titled A Rebel Against Injustice: Richard Kirkland, Young Humanitarian of Kershaw County, South Carolina: "The Kirklands were not rice bird-planters from Charleston. They came overland from Farquhar County, VA and settled in the Catawba Wateree Valley where the streams, the falls, the steep hills and giant boulders reminded them of Scotland. They were bred with the individualistic tendency of the self-reliant pioneers - the determination to do what they thought right - yet ready to take the consequences."

Richard was the son of John and Mary Kirkland whose relatives had long established a comfortable life farming in the fertile fields of the agricultural South. He was the youngest of 7 children (6 boys and 1 girl). Unfortunately Richard's mother passed away when he was just 2, although it has been written that this tragedy brought the family together. Sadly, there would be more tragedies for the Kirkland family to come.

The Kirkland's owned slaves, although I have been unable to validate exactly how many. One source I found stated there were 20, yet another tallied over 100. My guess is it's probably somewhere in between. Their plantation boasted large tracts of tobacco in White Oak, Gum Swamp, and the Flat Rock Regions of the county. I did read that many of their slaves escaped following "Sherman's March" into South Carolina that left the property devastated for years to come.

The family was indeed Christians and the children attended the Flat Rock Community Church and school. They were a close knit bunch and the relationships that they forged would carry into their adulthood. (On a side note, as I read about the Kirklands, I couldn't help but picture Jimmy Stewart's family in the film "Shenandoah," except of course the Kirkland's were all for the Southern Cause.)

Richard showed an aptitude for surveying and assisted with mapping out a 288-acre farmland near his family's homestead at the age of 16. Although the skill appeared to be a future for the lad, farming remained in his blood. He continued earning money through surveying jobs, but he used the profits to invest in farming tools.

Hard work was a way of life in the Kirkland house. So was the duty to one's country. At the onset of the Civil War, most of the males answered the "call to arms" and enlisted in the Confederate Army as volunteers. It was agreed among the brothers that one must stay home to protect the women and children and to control the slaves, as an uprising was feared. Lots were drawn and the duty of staying home was drawn by James, the eldest brother, much to his sorrow, but he abided by the agreement.

Although the rest of the Kirkland brothers did not all serve together in the same units, they did run into each other off and on during the war. Brother Jesse served with the 7th South Carolina. Dan and Billy deployed with the Kirkwood Rangers. Sam joined up with the 22nd S.C. Militia and later he would move on to the 7th South Carolina Cavalry following the death of his younger brother. He too would perish after being taken prisoner and contracting a disease at Point Lookout prison camp in Maryland. James, who had stayed behind, was tragically shot and killed on the plantation. By the time of the South's surrender, the family patriarch, John Kirkland will have lost his fortune, property, possessions, reputation, and three sons to the 'Great Divide.' Sadly, he died a broken man in 1870.

Following secession, Richard enlisted with the rebel forces before the age of 18. He had signed up as a private in the Camden Volunteers, who were later formed as the 2nd Regiment, South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. His neighbor, Captain John Kennedy was his immediate superior and the regimental commander was Colonel (and later General) Joseph B. Kershaw, a prominent attorney and officer. He is the gentleman pictured here beside Kirkland. Kershaw would also go on to become one of Kirkland's biggest promoters so to speak following the War Between the States. I'll share one of his tributes a little later on. Kirkland was later promoted to Sergeant a little over a year into the war.

Richard is said to have also helped recruit additional members into the S.C. Vols. This unit went right into the conflict arriving in Charleston during the bombardment of Fort Sumter. Although they would not fight in the war's first engagement, there would be few that they would not fight in throughout the war. Just look at this resume...At a first glance you can't help but ask were there any battles that they didn't participate in. Very few it seems. I have highlighted the two most noteworthy fights in relation to our discussion tonight, the battles of Fredericksburg and Chickamauga. The 'beginning' and the 'end' so to speak.

I'd like to read an essay from my book The Southern Cross that presents the extraordinary event that became the cornerstone of Kirkland's legacy: "Every Civil War writer has quoted either Union General William T. Sherman's statement of 'War is all Hell...,' or the Confederacy's supreme commander, Robert E. Lee, when he said 'It is well that war is so terrible-lest we should grow too fond of it.'

Both of these men were among the greatest generals ever to set foot on a battlefield, yet their obvious distaste for the very acts that made them legendary resonates from these lines. As a historian, one must always be careful not to "over-romanticize" war and to be constantly aware of the cold, sometimes harsh realities of the people and times that they portray. This is a dilemma that has plagued critics for centuries, resulting in both revisionist and apologist histories being written again and again.

However, for every heartbreak in wartime there has also been heroism, and for every tragedy, there has also been triumph. This is what makes the history of warfare worthy of our attention and justifies the energy we spend to preserve its memory for future generations. It is the good stories, the ones that reflect life (not death), the ones founded on courage and mercy that demand our interest. This is the side of war that truly needs to be glorified.

One such incident is the story of Sergeant Richard Rowland Kirkland, otherwise known as 'The Angel of Marye's Heights.' Perhaps the most compassionate and heroic character of the entire era, this lone Confederate soldier's conduct has become one of the most touching and inspirational subjects ever to come out of the War Between the States.

By the winter of 1862, Gen. Robert E. Lee's forces had claimed more decisive battlefield victories than their Northern counterparts due, in part, to the majority of engagements that took place on Southern soil. Throughout the first year of the war, the Confederates had managed to capitalize on a clear 'home field' advantage by dictating both the time and place of most major engagements. As a result, the Confederate States of America appeared to be well on their way toward achieving independence.

One of the biggest and most one-sided victories took place during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Early in the morning on December 13, 1862, Union forces began a desperate and doomed assault on a fortified position, known today as the 'stone wall at the sunken road.'

After crossing the Rappahannock River and taking possession of Fredericksburg, the Federal Army of the Potomac set its sights on taking the surrounding area where the Army of Northern Virginia had withdrawn. Perhaps a little too confident after experiencing only minor skirmishes in the town, the Union commanders failed to realize the brilliant tactical deployments established by Lee's lieutenants. By intentionally leaving the town to the enemy, Confederate forces were able to fortify their positions in anticipation of the arrival of the Federals. The most impenetrable of these positions was a long stone wall at the base of a sloping hill known as 'Marye's Heights.'

Overlooking the field stood another 'virtual' wall of Confederate artillery, cavalry and support troops that extended for miles in both directions. An attack would be a suicide mission. In order to reach the enemy, Union soldiers had to ford a canal ditch and then cross a vast open field with little or no cover. As soon as they left the tree line, a massive artillery barrage, joined by almost uncountable rifle fire, rained down upon the advancing men. Those that were able to escape the cannon were slowed by a slope that led to a fortified stone wall lining a sunken road. Behind the wall, soldiers knelt two and three ranks deep, with the front line firing and the rest reloading musket after musket. The result was a continuous hail of fire that cut rows and rows of men down before they could even get into position.

Wave after wave of Union soldiers left the safety of the canal ditch and were slaughtered. The death toll was staggering. In just one hour the Federals suffered more than 3,000 dead. After fifteen unsuccessful charges, the fighting ceased for the night, leaving the field littered with thousands of bloody bodies. Around midnight, Federal troops ventured forth under cover of darkness to gather what wounded they could find, but many were too close to the Confederate line to retrieve. Throughout the night, screams and cries of the wounded penetrated the peaceful silence of the cease-fire.

A Confederate soldier stationed at the wall later stated that it was 'weird, unearthly, terrible to hear and bear the cries of the dying soldiers filling the air -lying crippled on a hillside so many miles from home-breaking the hearts of soldiers on both sides of the battlefield.'

One soldier, Richard Rowland Kirkland, an infantry sergeant with the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, struggled to rest amidst the horrid sounds of suffering that echoed across the field. A combat veteran, he was accustomed to the dead and dying, having seen action at Manassas, Savage Station, Maryland Heights and Antietam. By the morning of the 14th, he could take it no longer and requested permission to aid the enemy. Initially, his commanding officer was reluctant, as Kirkland would likely be shot dead by Union sharpshooters when he cleared the wall. He later granted the persistent soldier his request, but forbid him to carry a flag of truce. Determined to do the right thing and with total disregard for his own safety, Kirkland grabbed several canteens and leaped over the fortification.

Instantly several shots rang out as the Union soldiers thought their wounded were under attack. Realizing the sincerity of Kirkland's effort, the Federal marksmen lowered the barrels of their rifles. Thus, the fatal shot never came and both sides looked on in amazement as the sergeant moved from one wounded man in blue to another. Going back and forth over the wall for an hour and a half, Kirkland only returned to the safety of his own lines after he had done all he could do.

A fellow soldier in Kirkland's company later recalled the incident in part of a short narrative for The Confederate Veteran that was published in 1903. He wrote, 'The enemy saw him and supposing his purpose was to rob the dead and wounded, rained shot and shell upon the brave Samaritan. God took care of him. Soon he lifted the head of one of the wounded enemy, placed the canteen to his lips and cooled his burning thirst. His motivation was then seen and the fire silenced. Shout after shout went up from friend and foe alike in honor of this brave deed.'

In the end, this soldier's action resulted in much more than a moment of mercy. It was a moment that stopped the entire Civil War and reminded those around him that, regardless of their circumstances, one should always strive to show compassion for his fellow man."

Mercy is the only way (in my opinion) that man can retain a sense of decency amidst the primitive circumstances of war. Perhaps that is why Kirkland's selfless action is celebrated even to this day? Years later General Kershaw himself would write to the editor of The News and Courier in January of 1880 presenting what he called "an accurate record of the events surrounding Richard Kirkland at Fredericksburg." He stated:

"With profound anxiety, he was watched as he stepped over the wall on his errand of mercy, Christ-like mercy. Unharmed he reached the nearest sufferer. He knelt beside him, tenderly raised the drooping head, rested it gently upon his own noble breast, and poured precious life giving fluid down the fever scorched throat. This done he laid him gently down, placed his knap-sack under his head, straightened out his broken limb, spread his over-coat over him, replaced his empty canteen with a full one, and turned to another sufferer.

By this time his purpose was well understood on both sides and all danger was over. From all parts of the field arose fresh cries of 'Water, for God's sake, water!' More piteous still, the mute appeal of some one who could only feebly lift a hand to say, here too is life and suffering. For and hour and a half did this ministering angle pursue his labor of mercy, nor ceased to go and return until he had relieved all of the wounded on that part of the field."

His commanding officer wasn't the only one touched by the Sgt's compassion. The Confederate veterans of Kershaw County so admired Richard Kirkland that they bypassed six Confederate generals born in Kershaw County and later named their organization "The Camp Richard Kirkland."

I had noticed while flipping through the bound volumes at the NPS archives that tributes abounded to this event, especially in publications that were issued during the Civil War Centennial period. I wonder if this is also an example of people looking to shine a light on a positive story from a war that had so few things to celebrate. One piece in particular that was published in 1962 by the Carolina Museum personifies this concept of elevating a mythical hero, by taking the truth and presenting assumptions that may or may not have been completely accurate. Clearly there is an agenda with articles like this. And I quote:

"The public must remember that this unassuming South Carolina farm boy held no bitterness or malice towards his enemies. He simply believed in a cause, and, for that cause, he died during the Battle of Chickamauga. At the instant of his death Richard Kirkland ceased to belong exclusively to the Confederacy and became a hero of national magnitude."

That is certainly a wonderful tribute, but in retrospect, it seems a tad inflated. At best this piece is compromised by some personal speculation. However, perhaps this is exactly what the descendants of the war's participant's wanted, or even needed at the time. In other words, maybe the public begged for Kirkland's story to justify the right to commemorate the war in the first place. It may therefore be case of simply embellishing something that transpired on the battlefield even though it was already worth remembering.

Why? Perhaps the tragic memory of brother versus brother was simply too painful to pursue. The biggest proof (in my opinion) of this intentional focus on 'presenting the positive' came in the form of a declaration that is printed in the Congressional Record Appendix from January 23, 1961. The record includes a formal statement that says: "The Civil War Centennial Committee has decided not to attempt to reenact any part of the battle in its program commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg to be held on December 13, 1962. But rather would the committee and the people of the North and South expand their energies in giving to their fellow countrymen and the world the story of Richard Kirkland who fought here and hallowed the ground upon which this bloody battle was fought."

Isn't that amazing? Here you have members of the U.S. government, South Carolinians, telling Virginia not to focus on the battle, but rather on the human interest story of a single soldier. It appears that the Battle of Fredericksburg became palatable only through this story of a Confederate's compassion.

Still, Fredericksburg was not the end of Kirkland's story. His life continued on and he accompanied his comrades in the victorious, yet bittersweet Battle of Chancellorsville, then up north to face the Federals on the fields at Gettysburg. Following the battle here, Kirkland was able to return home for a short time. There he was able to spend weeks with his sister Caroline and also his sweetheart, who was Susan Evelina Kirkland, the daughter of Major Daniel Kirkland and his second cousin. Little did they know it would be the last time they would meet.

Richard returned to the ranks of the Army of Northern Virginia just in time for the fight at Chancellorsville. Once again, the gods of war smiled upon the sergeant and he was able to emerge from the horrific engagement without a scratch. By the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, Kershaw had been promoted to a brigadier general in McLaw's Division of Longstreet's Corps. His regiments (including Kirkland's 2nd) fought in the woods and fields of the George Rose farm as well as the infamous Wheatfield. It is said that Kirkland performed with great courage and distinguished himself in battle. He was enthusiastically *promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. [*this has been disproved]

Many of Richard's companions were not as fortunate as he. Here we have a familiar image that was taken by photographer Timothy O'Sullivan on a visit to the Gettysburg battlefield on July 5-6, 1863. He captured dead South Carolinians from General Kershaw's Brigade, who were killed in fighting near this spot on July 2. The Confederate casualties were photographed exactly where they were laid to rest on the George Rose Farm. The comrades of these men only had time to dig the graves and carve initials on simple wooden headboards before they were ordered to leave the scene. Richard evaded wounding. His luck however was about to run out.

Kirkland's final fight would come during the bloody battle at Chickamauga. Here he would fall, yet be remembered in the same heroic fashion as he was after Fredericksburg. One eyewitness, who has been contested, but not disproven was a gentleman by the name of W.D. Trantham, who is said to have entered the army at the age of 13 and served with Kirkland. As he was apparently present at the Lieutenant's fatal wounding he presented a tribute to his fallen comrade. It is especially noteworthy as it specifically recalls the incident at Marye's Heights. It stated:

"The circumstances of his death were most heroic. He fought literally until the last gasp, and even in the very presence and moment of death showed that the sublime self-sacrifice and regard for others which he exhibited at Fredericksburg, was a settled principle of his nature. His command was hurled like a thunderbolt against the enemy who held a position that was nigh-impregnable. The line suffered a temporary check. Kirkland with two of his comrades, Ario Niles and James W. Arrants, were in the front of the line and reached an exposed knoll before they discovered that they were alone. They of course retired; but in doing so Kirkland, against the warning of his companions, persisted in turning and firing upon the advancing enemy. While thus engaged he was shot in the breast. Niles and Arrants ran to him and sought to bear him from the field. With blood spurting from wound and mouth he gasped: 'No, I am done for. You can do me no good. Save yourselves and tell my pa that I died right.' In a few minutes the line returned to the charge and drove the enemy from the field. Richard Kirkland's pure soul was with God."

Once again, we have a magnificent tale that is certainly rooted in fact, but written in a way that you can't help but be inspired when reading. Now Richard was only one of the tragic losses in this particular battle. I believe that half of the brigade was either wounded or killed there. Kirkland's body was removed from the field, sent back to his family in Kershaw County, and he was buried in a secluded spot on the White Oak Plantation. His grave marker was simple and had the initials R.R.K. carved into it. Fortunately his moment of courage and compassion at Fredericksburg was recorded for posterity and recognized by a handful of officers and enlisted men.

Following his death, many recalled the impact that this South Carolinian farm boy had on their lives during one of the darkest periods in American history. One of Richard's friends wrote: "I knew this brave boy; he was my friend and chum; we shared each other's blankets. He was a noble boy...He fought through all the Virginia battles in Longstreet's Corps, and was killed on the bloody field of Chickamauga...He did his duty and always answered the roll call. No nobler soul ever winged its flight from the field of battle...than that of Richard Kirkland...Sleep on, dear friend. Your old comrades will soon join you in your home of rest."

His Obituary that ran on October 16, 1863 also included a multitude of accolades such as: "Many gallant heroes have fallen, but not a more generous or gallant spirit has been sacrificed on our country's alter since the beginning of the war, than that of the one for whom this is intended as a feeble tribute. He was one of those who, knowing his duty was willing to discharge it, be the consequences what they might. He shunned no hardships, he shrunk from no danger. His was a steady course, making the path of duty the road which he was won't to travel…" And "…Young and gallant soldier rest in peace; fate has decreed that you should not reap the reward of all your toils; but your name stands recorded upon the long list of victories already sacrificed upon the altar of your country's liberty."

In 1909, a request was made to move the remains of Richard Kirkland from the family plot to the Quaker Cemetery in Camden. This was mostly suggested as his original place of rest was becoming overgrown. The notion of giving him a more prestigious burial so that others could honor him was granted. A large stone was sculpted and engraved to mark the final resting place of the one they had called an angel.

His tombstone reads: "Richard Kirkland, CSA, who at the Battle of Fredericksburg risked his life to carry water to wounded and dying enemies and at the Battle of Chickamauga laid down his life for his country."

As you can see people leave canteens at the site in tribute. Additional shrines to Richard Kirkland include a memorial fountain that was financed by school children in 1910 and of course the monument here in Fredericksburg. In 1965, this piece was sculpted by the famous artist Felix DeWeldon and unveiled in front of the stone wall on the Fredericksburg battlefield where Kirkland performed his humanitarian act. The inscription on the statue reads: "At the risk of his life, this American soldier of sublime compassion brought water to his wounded foes at Fredericksburg. The fighting men on both sides of the line called him the Angel of Marye's Heights."

So here we are tonight, living in the crossroads of the Civil War, standing just a few miles from the spot where a young man performed an extraordinary act of humanity. We have a library full of tributes and accolades recalling the event and elevating the man who performed with grace, and compassion - courage and selflessness. Some are embellished, others are not.

We also have a magnificent monument testifying to the best and worst of man. And shelves of souvenirs and paintings that depict this remarkably encouraging moment that will be forever frozen in time. Most importantly, we have the collective memory of a young man who was able to rise above the madness of war and extend a helping hand to those who were not 'really' his enemy.

In closing, I would like to quote an excerpt from a poem about Richard Kirkland that was penned by Walter Clark in 1908:

"Like Daniel of old in the lion's den,

He walked through the murderous air

No touch or tear his gray-clad form,

For the hand of God was there"

"And I am sure in the Book of Gold,

Where the blessed angel writes

He wrote that day with his shining pen

The Angel of Marye's Heights"

We can see that this man's memory is worthy of the myth and that his was a life that certainly touched Fredericksburg (and beyond) during the Civil War. It is a story that touched me, and I certainly hope that it touched you too. Thank you.

BUY The Angel of Marye’s Heights on DVD

This weekend the New York Yankees organization will commemorate the 50th anniversary of Roger Maris’ historic 1961 homerun season. Even the most ardent Yankees haters (to include my friend and

This weekend the New York Yankees organization will commemorate the 50th anniversary of Roger Maris’ historic 1961 homerun season. Even the most ardent Yankees haters (to include my friend and