BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Friday, 24 June 2011

I may actually like this

I have to give the TP credit when it's due. All politics and gaffes aside, I must say that a well-produced series on the Revolution-era really appeals to me.

The Tea Party movement has their own news network, and now, they're turning to admitted fiction. Having long accused Hollywood of raging liberalism, a group of conservatives have banded together to start Colony Bay Productions, according to The Hollywood Reporter, a startup production company that will create right wing-tinged content. Founded by Jonathan Wilson, an experienced Hollywood development executive, and James Patrick Riley, an experienced Patrick Henry impersonator, the company will debut its first show, “Courage, New Hampshire,” on Saturday night. With their interpretation of the founding fathers' intentions, and idealized belief in the purity of early American life, “Courage, New Hampshire” is an obvious start for the Tea Party company; set in the 1700s, it's a soap opera-style show that will go straight to DVD after its red carpet debut. They didn't pitch it to mainstream networks that are actually on TV. As Riley, who wrote, produced and appeared in the show, told THR, while they'll work to include Tea Partiers in the cast and crew, they, “hire anyone who can get the job done. We have cast members who are raging leftists.” READ MORE

Tuesday, 21 June 2011

The Founders did it too

As someone with a specialized degree in Visual Communications, I’m living proof that anyone can become a published 18th-19th century historian. That said, I would never have pictured a legendary pornographer joining our ranks. Yet that is exactly what happened when Hustler publisher and free speech-activist Larry Flynt teamed up with David Eisenbach, a professor of American political history at Columbia University. The result is a tremendously decadent and unique book titled, One Nation Under Sex: How the Private Lives of Presidents, First Ladies and Their Lovers Changed the Course of American History. According to the publisher, this book "peeks behind the White House bedroom curtains and documents how hidden passions have shaped America's public life."

As someone with a specialized degree in Visual Communications, I’m living proof that anyone can become a published 18th-19th century historian. That said, I would never have pictured a legendary pornographer joining our ranks. Yet that is exactly what happened when Hustler publisher and free speech-activist Larry Flynt teamed up with David Eisenbach, a professor of American political history at Columbia University. The result is a tremendously decadent and unique book titled, One Nation Under Sex: How the Private Lives of Presidents, First Ladies and Their Lovers Changed the Course of American History. According to the publisher, this book "peeks behind the White House bedroom curtains and documents how hidden passions have shaped America's public life."

Billed as a collection of “history changing sex scandals” these are the salacious tidbits that have been apparently whitewashed from American textbooks. In an interview for Salon magazine Flynt stated why he wrote the book in the first place: “Well, we're often preoccupied with it even in our present society. Over the last 30 years there were a lot of corrupt politicians – usually involving sexual scandals. I just thought it would be interesting to go back and start with the Founding Fathers and see if they still existed. I was amazed it was so prevalent.” Obviously meant to be more entertaining than educational, the intent of the book is serious nonetheless. And by co-authoring it with a professor from Columbia, Flynt has added an element of scholarship. Although I have yet to read it or examine its sources, I am intrigued to say the least, especially in the sections on the Founding Fathers.

So what did Flynt find? Of course Thomas Jefferson’s renowned sexual relationship with Sally Hemings, a slave girl who he fathered multiple children with is included, as well as Benjamin Franklin’s infidelities while living in France. Franklin, perhaps the biggest playboy of all the Founders is actually credited with publishing a tabloid newspaper that had the first-ever sex advice column. It seems that Flynt and Franklin may have been kindred spirits. James Madison’s wife Dolly (and her sisters) are said to have thrown epic parties at the early White House which often included lots of wine and members of the Continental Army. According to the book, one of the president’s cabinet members said to him, “I know you don't want to hear this, but your wife has single-handedly turned the White House into a brothel.” Alexander Hamilton’s rarely discussed sex scandal is included. Apparently Hamilton was having an affair with a married woman while serving as the secretary of the treasury. Her husband, a gentleman named James Reynolds, began to blackmail Hamilton until word of it reached Congress. Following a formal investigation, it was determined that Hamilton had not used any of the state money to cover his tracks and was entrapped by the situation.

Although I doubt that Larry Flynt will become the next Bruce Catton, he does have an obvious gift for salacious entertainment. At the least, "One Nation Under Sex" sounds like a great bedside read. In closing his interview for Salon, Flynt offered up the book’s affect on his own perspective of America by taking the rest of us to task. He said, “Historians really get under my skin because I think they're the most anal-retentive group of professionals I've ever met. They can look at Mount Rushmore and get writer's cramps. Historians never wanted to believe that this magnificent man who drafted the Declaration of Independence had actually fathered children by a black slave. The publishers of history books tend to be conservative and they only want to know about policy and politics. They don't want to know about sex. That's why it's left out of these books and has been for centuries.”

Monday, 20 June 2011

Didn't the Founders go global?

The key tenets of global citizenship include respect for any and all fellow global citizens, regardless of race, religion or creed and the ability to give rise to a universal sympathy beyond the barriers of nationality. These noble sentiments can be traced back to our country’s earliest origins when a revolutionary author and pamphleteer Thomas Paine published The Rights of Man. In it he said, “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.” The modern definition of global citizenship states: “In international relations, global citizenship can refer to states' responsibility to act with the awareness that the world is a global community, by recognizing and fulfilling its obligations towards the global world, as well as the rights of global citizens. Global citizenship is related to the international relations theory of idealism, which holds that all countries should include a level of moral goodwill in their foreign policy decisions towards one another.” It is my understanding that this does not mean to support others at the expense of your own country’s sovereignty or prosperity. It means to approach the world with the understanding that each country is part of a much bigger picture, and that countries can benefit from one another while working toward a common goal. This is nothing new. My church refers to the world as its mission field.

It is therefore very shocking to see the “anti-global movement” that has popped up among Tea Partiers and their supporters in recent years. The partisan resistance to the term “Citizen of the World” can be traced directly back to President Obama’s 2008 speech in Berlin. That moment forever changed a portion of the American public’s perspective on foreign relations. I will be the first to admit that there are a lot of President Obama’s policies that I don’t agree with. That said, I cannot believe that a more-global-minded approach to politics is not only desirable, but absolutely necessary to survive in 2011.

If Americans are wondering why the rest of the world is passing us by, perhaps they should look no further than this "superior-isolationist" attitude that some folks profess. I seem to recall the last administration burning an awful lot of bridges in support of their maverick agenda.

Not surprising, Glenn Beck has been one of the most outspoken critics of the concept. On his May 25th episode of The Glenn Beck Show he stated, “Tonight, we're kind of introducing something that we'll spend some time on history with in the coming days and weeks. But I have been telling you tonight about the push for globalization. I left my citizen of the world ID in my other pants. I hope they don't deport me now from the planet. There is no such thing as citizen of the world. We're Americans. We're humans. We're on planet earth, but we are Americans. But for Obama, it's time we all just come together. It's not good for America because you've got to equal out the entire world. If you understand the global governance thing that the world, I think, is trying to knit us together on, you'll understand why the president and his allies don't ever want to talk about American Exceptionalism. But America is an exceptional place. We've been an exceptional place because we are a special land.”

It may be an oversimplified critique, but I think that sounds pretty damn conceited and selfish in my opinion. The Tea Party has also been very upfront about this subject. On their website at teaparty.org, they post “Globalization spells the end of America.” I was thinking about this brash statement last week when I began to look at the Founding Fathers as global citizens. Once again, I think the TP folks have contradicted their own branding.

Weren’t Franklin, Jefferson and Adams (all Tea Party darlings) citizens of the world? Let’s examine their contributions abroad…

“It is a common observation here (Paris) that our cause is the cause of all mankind, and that we are fighting for their liberty in defending our own.” - Ben Franklin, Letter to Samuel Cooper, 1777

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in France as America's first ambassador, there were two major superpowers in Europe: England and France. Ambassador Franklin’s primary goal was to secure French aid to for the United States and although he spent the vast majority of his time kibitzing with the intellectuals and upper classes, he did develop a penchant for the plight of France’s peasant population. Franklin lived in France for a period of nine years and became an immensely popular and beloved resident of the quaint town of Passy, which was located just outside of the city of Paris. As the Minister to France, Franklin was a major player in the frontline politics involving much of Europe and the United States. A skilled diplomat, he negotiated treaties with Great Britain, France, Germany, Sweden, and Spain and helped secure America’s place in the world. As a respected scientist and scholar, he was granted honorary degrees in England, Scotland, and America. And as an Enlightenment thinker, he exchanged letters with some of the greatest minds of the eighteenth century. When Franklin left to return to America in 1785, he was replaced by fellow Founder Thomas Jefferson who wrote of his departure, “When he left Passy, it seemed as if the village had lost its patriarch.” Franklin died a mere five years later. Surprisingly it was his adopted home of France that mourned him with the pomp and ceremony befitting a man of his accomplishments. Even today, Ben Franklin remains a major figure in French history. According to Franklin historian Claude-Anne Lopez, “Many French think he was president of the United States. They say, ‘he was the best president you ever had!’”

“Be assured I shall ever retain a lively sense of all your goodness to me, which was a circumstance of principal happiness to me during my stay in Paris.” – Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Madame d'Enville, 1790

Franklin’s replacement, Thomas Jefferson, also became a well known and respected American representative, living on French soil from 1784-1789. Unlike Franklin, he was accompanied by his twelve-year-old daughter Martha (Patsy) and William Short as personal secretary. James Hemings, his nineteen-year-old slave, followed soon after to attend cooking school. Jefferson first took up residence at the Hôtel de Landron and then at the Hôtel de Langeac on the Champs-Elysées. Boasting relationships with some of the most powerful people in the country to include King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, he often appeared at the ministers' offices at the Palace of Versailles and when not attending to political affairs he immersed himself in French culture. In spring of 1785, John Adams and Jefferson successfully negotiated a loan from Dutch bankers to consolidate U. S. debts, pay long overdue salaries to French officer veterans of the American Revolution, and ransom American captives held by Algerian and Moroccan rulers. In May of 1789 Jefferson attended the opening of the French Estates-General and its debates at Versailles. He then drafted a charter of rights with Lafayette in June which served as the basis for the French Declaration of Rights that Lafayette presented to the National Assembly in July.

“Your Proposal of coming to me would make me the happiest of Men, if it were probable that I should live here where I am well settled. But, if the Negotiations for Peace should take a serious Turn, I shall be obliged to live in furnished Lodgings at Paris, or to travel 600 or 800 miles farther to Vienna.” – John Adams, Letter to Abigail, 1782

John Adams joined both Franklin and Jefferson in France before serving as an ambassador to the Netherlands. Accompanied by his eldest son, John Quincy, he represented America in the Dutch Republic, Republic of Venice and the Old Swiss Confederacy. In October 1782, Adams negotiated with the Dutch a treaty of amity and commerce, the first such treaty between the United States and a foreign power following the 1778 treaty with France. And with the aid of the Dutch Patriot leader Joan van der Capellen tot den Pol, he was able to secure the recognition of the United States as an independent government. During this visit, he also negotiated a loan of five million guilders financed by Nicolaas van Staphorst and Wilhelm Willink. The house that Adams bought during this stay in The Netherlands became the first American-owned embassy on foreign soil anywhere in the world. In 1784 and 1785, Adams was one of the architects of far-going trade relations between America and Prussia. Abigail Adams traveled to France in 1784 to join her husband. Soon afterward, Congress appointed him as the first United States ambassador to Britain's Court of St. James. In England from 1785-88, the Adamses regularly heard Unitarian Richard Price preach at Gravel Pit Chapel, Hackney. Adams enjoyed the English minister's friendship. He was also acquainted with Joseph Priestley, Theophilus Lindsey, Thomas Belsham, and many other British Unitarians. Adams's home in England, a house off London's Grosvenor Square, still stands and is commemorated by a plaque.

Thursday, 16 June 2011

Jefferson's Religious Freedom (Originally published Nov. 2008)

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...

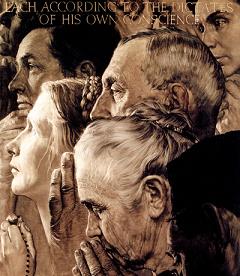

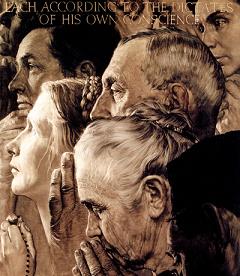

In today's age of divisive and unashamedly biased politics, it is very easy for our nation's citizens to become confused with regard to the principles upon which our country was founded. Both liberals and conservatives routinely lay claim to historical doctrines that they believe support, and in some cases mandate, their own political agendas. Perhaps no other government legislation is more misunderstood or contested than that which describes the "separation of church and state." Non-believers have traditionally argued that this declaration prohibits the recognition of any religion in the public arena, while believers from a variety of faiths argue that it does the exact opposite.

Most bothersome is the lack of knowledge that many people on both sides of the argument possess on the matter. The fact is that the U.S. Constitution, a completely secular document, contains no references to God, Jesus, or Christianity. It says absolutely nothing about the United States being officially founded as a Christian nation. On the other hand, the Declaration of Independence clearly refers to "the Creator" when it states, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

That is as close as we come to a formal "God" endorsement. The fact of the matter is, the literal phrases "church and state," or "separation of church and state" do not appear anywhere in our nation's founding documents. Unfortunately, far too many people today believe that it does.

This does not mean that the Framers were anti-religious. In fact, many of the Founding Fathers belonged to one of the following denominations: Episcopalian/Anglican, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Quaker, Dutch/German Reformed, Lutheran, Catholic, Huguenot, Unitarian, Methodist, and Calvinist, although not all were actively practicing. Many would more likely be considered Deists more than traditional Christians, and some even believed that the practice of organized religion was a sin in itself. Other Founders practiced a more traditional bible-based lifestyle and considered the open practice of a chosen faith a "must" for the new country. Freedom from England meant freedom from the Church of England.

In order to fully understand what freedoms and limitations exist in America within the "separation of church and state," it is essential that one studies the intentions and beliefs of the principle's creator.

Truly an enlightened man of the 18th-century renaissance, Thomas Jefferson remains one of the most celebrated and examined politicians in the history of our nation. Some experts have even gone as far as to state that he was the most "civilized" citizen ever to come from the American Revolution era. He is directly credited with helping to create an infinitely prosperous nation that is rich in individual potential, liberty, and freedom. Jefferson's Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom was first proposed in 1779. The General Assembly adopted it in 1786. This act was passed by both houses and has since become a part of the Virginia Constitution. The principles and language of this unique document have inspired supporters of religious freedom around the world to adopt similar principles.

READ: Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (annotated transcript)

Jefferson originally agreed to author a bill for religious liberties in America while visiting the small town of Fredericksburg, Virginia. After attending a meeting with his contemporaries at an establishment known as ‘Weedons Tavern,' he penned the statute which separated church and state and gave equal status to all faiths. It became the basis for the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving all Americans the freedom to practice their religion, or none at all.

He wrote that "The rights [to religious freedom] are of the natural rights of mankind, and... if any act shall be... passed to repeal [an act granting those rights] or to narrow its operation, such act will be an infringement of natural right."

Jefferson himself proclaimed this bill to be one of his three most gratifying achievements, along with authoring the Declaration of Independence and founding Virginia University. Today, the Religious Freedom Monument proudly stands in Fredericksburg as a testament to that event. The simple marker was first unveiled in 1932 and was moved to its present location in the town at Washington Avenue Mall at Pitt Street in 1977. The monument consists of small obelisk made of hewn stone blocks and pays tribute to Jefferson's words. There are perhaps hundreds of statues, paintings, and monuments spread all across the nation that salute the remarkably fruitful life of Thomas Jefferson. This one is perhaps the most overlooked.

Jefferson is also a perplexing personality when considering the practice of faith. In a letter written to his associate, John Adams, in January of 1817, he boldy states, "Say nothing of my religion. It is known to my god and myself alone."

So what were Jefferson's personal feelings on spirituality, and why was his statute for religious freedom one of the three things that he deemed worthy enough to inscribe on his grave marker? Certainly in addition to authoring the Declaration of Independence and founding Virginia University, this act remained so near and dear to his heart that he wanted to preserve it for eternity.

Religion remains a hotly debated aspect of Thomas Jefferson's legacy. Some claim that he was simply a Deist, while others have accused him of having no faith at all. Jefferson would have been "officially" categorized as a reformed Protestant and was raised as an Episcopalian (Anglican). However, his tendency for wanting to posses a broader knowledge and understanding of all things led him to be influenced by English Deists who believed in the concept that a higher power did indeed exist, but that man's affairs were not under its influence.

He also held many beliefs in common with Unitarians of the period, and sometimes wrote that he thought the whole country would eventually become a Unitarian society. Jefferson recorded that the teachings of Jesus contain the "outlines of a system of the most sublime morality which has ever fallen from the lips of man." He added, "I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know."

Although his specific denominational and congregational ties were limited in his adulthood and his ever-evolving theological beliefs were distinctively his own, Jefferson was by his own admission, a progressive "Christian" if only in intent. He attended Episcopalian services as president, but his manipulation and rewriting of the Christian bible certainly speaks to a man who was both curious and conflicted. He once wrote, "I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished anyone to be..." This aspect of Jefferson's personal belief system remains among the most controversial and debated of all. Bible scholars have accused him of being both a genius and an atheist. Only the former is true.

Jefferson rejected the "divinity" of Jesus, but he believed that Christ was a deeply interesting and profoundly important moral or ethical teacher. He also subscribed to the belief that it was in Christ's moral and ethical teachings that a civilized society should be conducted. Cynical of the miracle accounts in the New Testament, Jefferson was convinced that the authentic words of Jesus had been contaminated.

His theory was that the earliest Christians, eager to make their religion appealing to the pagans, had obscured the words of Jesus with the philosophy of the ancient Greeks and the teachings of Plato. These so-called "Platonists" had thoroughly muddled Jesus' original message. Firmly believing that reason could be added in place of what he considered to be "supernatural" embellishments, Jefferson worked tirelessly to compose a shortened version of the Gospels titled "The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth." The subtitle stated that the work was "extracted from the account of his life and the doctrines as given by Matthew, Mark, Luke & John."

On April 21, 1803, Jefferson sent a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush, who was a fellow ‘Founding Father' and devout Christian, explaining his own interpretation of scripture.

Dear Sir,

In some of the delightful conversations with you in the evenings of 1798-99, and which served as an anodyne to the afflictions of the crisis through which our country was then laboring, the Christian religion was sometimes our topic; and I then promised you that one day or other I would give you my views of it. They are the result of a life of inquiry and reflection, and very different from that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed, but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished anyone to be: sincerely attached to his doctrines in preference to all others, ascribing to himself every human excellence, and believing he never claimed any other. At the short interval since these conversations, when I could justifiably abstract my mind from public affairs, the subject has been under my contemplation. But the more I considered it, the more it expanded beyond the measure of either my time or information. In the moment of my late departure from Monticello, I received from Dr. Priestley his little treatise of "Socrates and Jesus Compared." This being a section of the general view I had taken of the field, it became a subject of reflection while on the road and unoccupied otherwise. The result was, to arrange in my mind a syllabus or outline of such an estimate of the comparative merits of Christianity as I wished to see executed by someone of more leisure and information for the task than myself. This I now send you as the only discharge of my promise I can probably ever execute. And in confiding it to you, I know it will not be exposed to the malignant perversions of those who make every word from me a text for new misrepresentations and calumnies. I am moreover averse to the communication of my religious tenets to the public, because it would countenance the presumption of those who have endeavored to draw them before that tribunal, and to seduce public opinion to erect itself into that inquisition over the rights of conscience which the laws have so justly proscribed. It behooves every man who values liberty of conscience for himself, to resist invasions of it in the case of others; or their case may, by change of circumstances, become his own. It behooves him, too, in his own case, to give no example of concession, betraying the common right of independent opinion, by answering questions of faith which the laws have left between God and himself. Accept my affectionate salutations.

- Th: Jefferson

In 1820 Jefferson returned to his controversial New Testament research. This time, he completed a much more ambitious work titled "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth Extracted Textually from the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French and English." The text of the New Testament appears in four parallel columns in four languages. Jefferson omitted the words that he thought were inauthentic and retained those he believed were original. The resulting work is commonly known as the "Jefferson Bible."

READ: The Jefferson Bible (online edition)

Clearly, religion played a major role in the intellectual life of Thomas Jefferson. Whether his views and practices failed to fit into a traditionally-organized Christian-Judea doctrine, his exhaustive examination, dissection, and authoring of religious studies prove that spirituality mattered to him. Therefore, for anyone to imply that his statute of freedom was created to stifle the practice of religion is completely illogical.

Thomas Jefferson was a believer. He absolutely believed in a higher power by referencing "the Creator." And he believed that everyone within America's borders deserved the right to believe and worship, or not believe and disregard. He also believed in the moral teachings of the one referred to as Jesus Christ, whether he was the Messiah or not. In a letter sent to Harvard Professor Benjamin Waterhouse in 1822, Jefferson stated, "The doctrines of Jesus are simple, and tend all to the happiness of man."

So it is entirely within reason to believe that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom to empower and protect believers and non-believers alike and not to impose restrictions on them. The key word to understanding this document is contained in its very title, "Freedom." Freedom was the most important attribute that the Founding Fathers wished to achieve. Freedom was the keystone in the foundation of the United States of America.

Freedom of religion meant that all people had an equal right to practice their spiritual doctrines without having to worry about the government challenging, or even limiting them.

In his mind, this free will of spiritual expression belonged to everyone including Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and what we would refer to in modern times as New Age practitioners. At the same time, Atheists and Pagans also shared in the very same freedom to either reject or pursue their own beliefs. Thanks to the foresight and brilliance of Thomas Jefferson and his contemporaries, we all have the freedom to believe or not; the freedom to attend church or not; and the freedom to pray or not.

To sanction or officially recognize a single faith (such as Christianity) would have not only been contrary to the Founder's intent, it would have marginalized a portion of society. This statute was all about inclusiveness. This means that all believers have the exact same liberties, regardless of the fact that their belief systems are completely opposed to one another. For example, the Christian is protected from the government mandating that he or she has to follow a particular denomination and the Atheist is protected from the government mandating that he or she believe at all. It's a brilliant and liberating concept when exercised in the manner it was intended.

The "common-sense" practice of uninhibited religious freedom continued until the late 20th-century when individual special-interest groups began to take offense to public religious practices and what appeared to be governmental sanctions of religious holidays. Many petitions appeared in court where groups of believers and non-believers alike argued whether the other side had any right to express their beliefs at all. This litigious conflict spilled out into the public square where religious symbology came under scrutiny. Public prayer and displays were removed in some sectors. Religious slogans and events were also contested.

Unfortunately, like many of our nation's principles, this one has been skewed, even corrupted at times, to imply that the "separation of church and state" means that all forms of religion cannot be celebrated and/or expressed within the public square. These misguided and ultimately petty arguments would no doubt irritate our Founders, especially Thomas Jefferson who fervently believed the opposite.

Here was an open-minded man who had the foresight to see a unified society, where people of different faiths lived secure in knowing that they all shared the same liberty to express their beliefs (or not) without worrying about the intolerance or interference of the government. The irony of this debate is that in challenging the spiritual beliefs of others, we have, as a country, inevitably stifled the very freedom that is granted to us by the "separation of church and state." Mr. Jefferson did not want his prized statute to result in the forced removal of all religious practices and references from the public square. He wanted it to allow all people the option to practice religion according to their beliefs, or not practice religion at all, because according to his own pen, "we all are endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable Rights," no matter who that Creator is, or is not, to us.

By Michael Aubrecht for The Jefferson Project, Nov., 2008

Monday, 13 June 2011

The Luckiest Guy

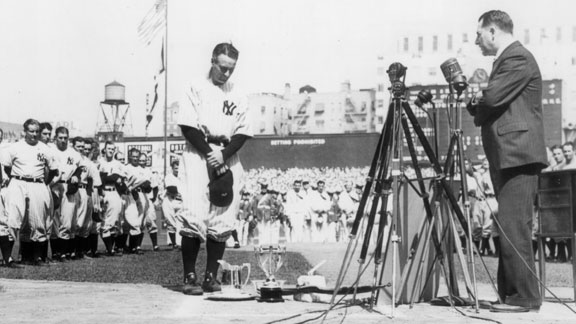

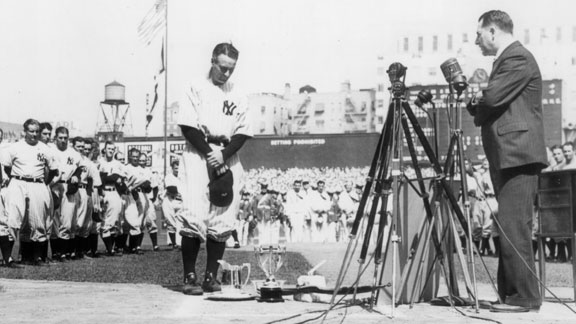

ABOVE: Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium, July 4, 1939.

Today’s post is a little 'off-topic' as it presents another one of my favorite genres of historical study, baseball. My first 'paid-gig' as a writer was that of a contributing historian for Baseball-Almanac.com (2000-2006). Next spring, Eric Wittenberg and I will debut our new book titled You Stink! Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players (The Kent State University Press). The anticipation that is already buzzing around this title is very much appreciated and I for one cannot wait to promote it. This past weekend I shared a rather lengthy, and in-depth conversation with a Red Sox aficionado who was willing to acknowledge that there was at the very least, one Yankee he admired. This one's for him...

Lou Gehrig’s performance on the field made him an American icon, but it was his tragic and untimely death that made him unforgettable. A real-life folk hero, Gehrig was everything a professional baseball player should and shouldn’t be. A quiet man who “carried a big stick,” Gehrig was a blue-collar champion. His records and statistics spoke louder than his actions and his career numbers still rank among the highest in the history of Major League Baseball. As a member of baseball’s most storied franchise, his accomplishments with the first Yankees dynasty are without question. His dedication to the game was certainly second to none, yet beyond baseball, there was nothing newsworthy or spectacular about him. In the words of his widow, Eleanor, “He was just a square, honest guy.”

Simply stated, Lou Gehrig was a baseball player…a great baseball player. All-Century Teammate, Hall of Famer, Triple Crown Winner, All-Star, World Series Champion, Most Valuable Player… these are just some of the terms used to describe the one they called “The Iron Horse.” Unlike the players of today, Gehrig spent his entire professional career with the same team while wearing the blue pinstripes in his hometown of New York City. His life story represented the “American Dream” and read more like a Hollywood movie script. Surprisingly more fact than fiction, it was appropriately translated into THE PRIDE OF THE YANKEES, which was nominated for eleven Academy Awards in 1943 and is still regarded by many today as the finest baseball movie ever made. His statistics spoke volumes as well and continue to prove that his impact on our national pastime remains second to none by a player from his era.

For starters, his lifetime batting average was .340, fifteenth all-time highest, and he amassed more than 400 total bases in five seasons. A player with few peers, Gehrig remains one of only seven players with more than 100 extra-base hits in one season. During his career he averaged 147 RBIs a year and his 184 RBIs in 1931 still remains the highest single-season total in American League history. Always at the top of his game, Gehrig won the Triple Crown in 1934, with a .363 average, 49 homers, and 165 RBIs, and was chosen Most Valuable Player in both 1927 and 1936. Unbelievable for a man of his size, #4 stole home 15 times, and he batted .361 in 34 World Series games with 10 homers, eight doubles, and 35 RBIs. Still standing is his record for career grand slams with 23. Gehrig hit 73 three-run homers, as well as 166 two-run shots, giving him the highest average of RBIs (per homer) of any player with more than 300 home runs. Not bad for a guy who originally entered Columbia University with the intention of becoming an engineer!

For most ballplayers, this would have been more than enough fare for a ticket to Cooperstown, but for Gehrig, the aforementioned stats are only a glimpse into his brilliant career. Still the only player in history to drive in 500 runs in three years, he also hit 493 home runs (while playing first), the most by any first baseman in history. On June 3, 1932, Gehrig became the first American Leaguer to hit four home runs in a game and he was the first athlete to have his number officially retired in 1939. A true thoroughbred, he was christened the “Iron Horse” when he held the “unbreakable” record of 2,130 consecutive games played, until 1998, when it was finally topped by another “Iron Man” named Cal Ripken Jr. A tireless worker, Gehrig played every game for more than 13 years despite a broken thumb, a broken toe and back spasms. Later in his career, his hands were X-rayed and doctors were able to spot 17 different fractures that had “healed” while he continued to play. This toughness could be attributed to the fact that he was the only surviving child (out of 4) of hard-working German immigrants. Somehow though, even his resilient exterior could not overcome the growing sickness he hid within.

Things began to change in 1938 as Gehrig struggled and fell below .300 for the first time since 1925. He appeared clumsy and sluggish on (and off) the field and it was painfully clear that there was something wrong. He lacked his usual dominant swing and many pitches that he would have normally hit out of the ballpark fizzled into meager fly outs. Initially, doctors diagnosed him with having a gall bladder problem and put him on a bland diet, which only made him weaker. Determined to work through his pain, he managed to play in the first eight games of the 1939 season, but fatigue weighed on his bat and he was barely able to field the ball. Gehrig knew that when his fellow Yankees had to congratulate him for stumbling into an average catch, it was time for him to leave. Eventually, he took himself out of the game and unfortunately, he would never return.

After a battery of tests, doctors at the Mayo Clinic diagnosed Gehrig as having a very rare form of degenerative disease called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The prognosis was terminal and there was no chance that he would ever play baseball again. Aware that his days were numbered, he continued to carry himself with unwavering dignity, despite being unable to conceal his failing health.

Local sports writer Paul Gallico suggested that the team should have a recognition day to honor Gehrig on July 4, 1939. In attendance were Mom and Pop Gehrig, Eleanor Gehrig (wife), and all the 1939 Yankees with manager Joe McCarthy. Other guests included Bob Meusel, Bob Shawkey, Herb Pennock, Waite Hoyt, Joe Dugan, Mark Koenig, Benny Bengough, Tony Lazzeri, Arthur Fletcher, Earle Combs, Wally Schang, Wally Pipp, Everett Scott, New York Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia, US Postmaster General James A. Farley, and the New York baseball writers dean and MC for the ceremony, Sid Mercer. Babe Ruth showed up late, as was his typical fashion, and drew a loud cheer from the crowd. Gehrig was touched that there were so many people there on his behalf, but he had mixed emotions about Ruth being there. The two, once good friends, had not spoken in years.

Gehrig historian Sara Kaden Brunsvold, recalled the ceremony:

During the first game, Gehrig stayed in the Yankee dugout anxiously awaiting the ceremony that would take place at home plate at the end of the game. Similarly Joe McCarthy was fretting over the words he would say to Gehrig during the ceremony. Neither man thought himself articulate, and neither looked forward to having so many eyes on them. Whereas Gehrig decided to do the best he could with the impending ceremony, McCarthy was so nervous he became irritable. But he still had presence of mind enough to notice how frail Gehrig looked, and he pulled some of the Yankees players aside and told them to watch Gehrig during the ceremony in case he should start to collapse.

Finally the first game was over and workers set up a hive of microphones behind home plate. The Yankee players of the current year and yesteryear lined up along the foul lines. Gehrig was placed near the microphones. A line of well-wishers from various occupations and fame came to the mics to say sweet, sweet things to Gehrig and about Gehrig. Some tears escaped from his eyes while he nervously, humbly hung his head and made a small circle of impressions in the dirt with his spikes. He took every word said to heart.

McCarthy came to the mics to say his piece with limbs trembling just as much as Gerhig’s. Despite his uneasiness, McCarthy was as heartfelt as he could manage, fighting the urge to bawl like a baby out of respect to Gehrig’s shaky emotions. Because McCarthy and Gehrig were very close, almost a father-son relationship, McCarthy knew that if he started crying it would probably make things that much worse for Gehrig trying to get through the ceremony. The most memorable part of his speech was when he assured Gehrig that no matter what Gehrig thought of himself, he was never a hindrance to the team.

Gehrig was given a number of presents, commemorative plaques, and trophies. Some came from the big-wig people; and, touching, some came from folks of the Stadium’s janitorial service and groundskeepers. The most talked about present Gehrig received was a silver trophy with all the Yankee players’ signatures on it presented by McCarthy. Inscribed on the front was a poem the Yankees had asked Times writer John Kieran to pen:

We’ve been to the wars together,

We took our foes as they came;

And always you were the leader,

And ever you played the game.

Idol of cheering millions;

Records are yours by sheaves;

Iron of frame they hailed you,

Decked you with laurel leaves.

But higher than that we hold you,

We who have known you best;

Knowing the way you came through

Every human test.

Let this be a silent token

Of lasting friendship’s gleam

And all that we’ve left unspoken.

- Your Pals on the Yankee Team

With more than 62,000 fans in attendance, Gehrig slowly stepped up to a bank of microphones and spoke those immortal words of thanks in one of the most heartfelt speeches ever given. As a testament to his courage and selflessness, he opened his remarks with the famous line, “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.”

He continued: “I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans. Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert - also the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow - to have spent the next nine years with that wonderful little fellow Miller Huggins - then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology - the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy! Sure, I’m lucky. When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift, that’s something! When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies, that’s something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles against her own daughter, that’s something. When you have a father and mother who work all their lives so that you can have an education and build your body, it’s a blessing! When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed, that’s the finest I know. So I close in saying that I might have had a tough break - but I have an awful lot to live for!”

His obituary, as printed in the New York Times, outlined his contributions to the community both on the baseball field and off:

...Regarded by some observers as the greatest player ever to grace the diamond, Gehrig, after playing in 2,130 consecutive championship contests, was forced to end his career in 1939 when an ailment that had been hindering his efforts was diagnosed as a form of paralysis. ...But as brilliant as was his career, Lou will be remembered for more than his endurance record. He was a superb batter in his heyday and a prodigious clouter of home runs. The record book is liberally strewn with his feats at the plate.

As a fitting tribute, Lou Gehrig was elected to the Hall of Fame that December. During the last months of his life, he worked on youth projects for New York until he was unable to walk. He died in 1941, at the age of 37. He was cremated, and his remains are in Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, roughly, 45 minutes from Manhattan. A headstone for Gehrig was erected that mistakenly claims he was born in 1905 (he was really born in 1903). His sudden death brought national attention to this relatively unknown affliction known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the illness has since been renamed “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”. His position in the public eye helped to inspire more intensive research and today the ALS medical community is hopefully getting closer to finding a cure.

The tragedy of his death still resonates today with baseball historians, players and fans all around the world. And it is important that we all remember that his contributions as a man far exceed those of a mere ballplayer. Lou Gerhig proved that anyone could achieve his or her dreams through hard work and determination. He then exhibited an iron-man work ethic that has only been broken once in the history of the game. Finally, he showed how courage and class could carry one through the most difficult of times.

Lou Gehrig accomplished more in his short life than most athletes could ever dream. He was a pure ballplayer at a time when the game was pure. As the years go by, so does the distance between young fans and the players of Gehrig’s era. Their game was timeless and we may never experience baseball as it was experienced back then.

EXTRA: Lou Gehrig's Lifetime Statistics at Baseball-Almanac.

Newer | Latest | Older

As someone with a specialized degree in Visual Communications, I’m living proof that anyone can become a published 18th-19th century historian. That said, I would never have pictured a legendary pornographer joining our ranks. Yet that is exactly what happened when Hustler publisher and free speech-activist Larry Flynt teamed up with David Eisenbach, a professor of American political history at Columbia University. The result is a tremendously decadent and unique book titled,

As someone with a specialized degree in Visual Communications, I’m living proof that anyone can become a published 18th-19th century historian. That said, I would never have pictured a legendary pornographer joining our ranks. Yet that is exactly what happened when Hustler publisher and free speech-activist Larry Flynt teamed up with David Eisenbach, a professor of American political history at Columbia University. The result is a tremendously decadent and unique book titled,

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...