BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Thursday, 16 June 2011

Jefferson's Religious Freedom (Originally published Nov. 2008)

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...

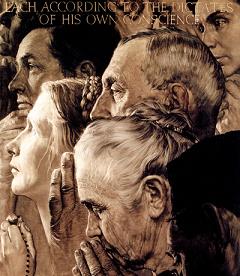

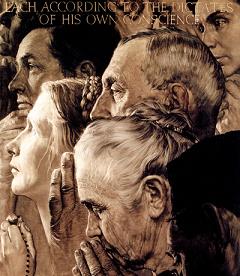

In today's age of divisive and unashamedly biased politics, it is very easy for our nation's citizens to become confused with regard to the principles upon which our country was founded. Both liberals and conservatives routinely lay claim to historical doctrines that they believe support, and in some cases mandate, their own political agendas. Perhaps no other government legislation is more misunderstood or contested than that which describes the "separation of church and state." Non-believers have traditionally argued that this declaration prohibits the recognition of any religion in the public arena, while believers from a variety of faiths argue that it does the exact opposite.

Most bothersome is the lack of knowledge that many people on both sides of the argument possess on the matter. The fact is that the U.S. Constitution, a completely secular document, contains no references to God, Jesus, or Christianity. It says absolutely nothing about the United States being officially founded as a Christian nation. On the other hand, the Declaration of Independence clearly refers to "the Creator" when it states, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

That is as close as we come to a formal "God" endorsement. The fact of the matter is, the literal phrases "church and state," or "separation of church and state" do not appear anywhere in our nation's founding documents. Unfortunately, far too many people today believe that it does.

This does not mean that the Framers were anti-religious. In fact, many of the Founding Fathers belonged to one of the following denominations: Episcopalian/Anglican, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, Quaker, Dutch/German Reformed, Lutheran, Catholic, Huguenot, Unitarian, Methodist, and Calvinist, although not all were actively practicing. Many would more likely be considered Deists more than traditional Christians, and some even believed that the practice of organized religion was a sin in itself. Other Founders practiced a more traditional bible-based lifestyle and considered the open practice of a chosen faith a "must" for the new country. Freedom from England meant freedom from the Church of England.

In order to fully understand what freedoms and limitations exist in America within the "separation of church and state," it is essential that one studies the intentions and beliefs of the principle's creator.

Truly an enlightened man of the 18th-century renaissance, Thomas Jefferson remains one of the most celebrated and examined politicians in the history of our nation. Some experts have even gone as far as to state that he was the most "civilized" citizen ever to come from the American Revolution era. He is directly credited with helping to create an infinitely prosperous nation that is rich in individual potential, liberty, and freedom. Jefferson's Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom was first proposed in 1779. The General Assembly adopted it in 1786. This act was passed by both houses and has since become a part of the Virginia Constitution. The principles and language of this unique document have inspired supporters of religious freedom around the world to adopt similar principles.

READ: Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (annotated transcript)

Jefferson originally agreed to author a bill for religious liberties in America while visiting the small town of Fredericksburg, Virginia. After attending a meeting with his contemporaries at an establishment known as ‘Weedons Tavern,' he penned the statute which separated church and state and gave equal status to all faiths. It became the basis for the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, giving all Americans the freedom to practice their religion, or none at all.

He wrote that "The rights [to religious freedom] are of the natural rights of mankind, and... if any act shall be... passed to repeal [an act granting those rights] or to narrow its operation, such act will be an infringement of natural right."

Jefferson himself proclaimed this bill to be one of his three most gratifying achievements, along with authoring the Declaration of Independence and founding Virginia University. Today, the Religious Freedom Monument proudly stands in Fredericksburg as a testament to that event. The simple marker was first unveiled in 1932 and was moved to its present location in the town at Washington Avenue Mall at Pitt Street in 1977. The monument consists of small obelisk made of hewn stone blocks and pays tribute to Jefferson's words. There are perhaps hundreds of statues, paintings, and monuments spread all across the nation that salute the remarkably fruitful life of Thomas Jefferson. This one is perhaps the most overlooked.

Jefferson is also a perplexing personality when considering the practice of faith. In a letter written to his associate, John Adams, in January of 1817, he boldy states, "Say nothing of my religion. It is known to my god and myself alone."

So what were Jefferson's personal feelings on spirituality, and why was his statute for religious freedom one of the three things that he deemed worthy enough to inscribe on his grave marker? Certainly in addition to authoring the Declaration of Independence and founding Virginia University, this act remained so near and dear to his heart that he wanted to preserve it for eternity.

Religion remains a hotly debated aspect of Thomas Jefferson's legacy. Some claim that he was simply a Deist, while others have accused him of having no faith at all. Jefferson would have been "officially" categorized as a reformed Protestant and was raised as an Episcopalian (Anglican). However, his tendency for wanting to posses a broader knowledge and understanding of all things led him to be influenced by English Deists who believed in the concept that a higher power did indeed exist, but that man's affairs were not under its influence.

He also held many beliefs in common with Unitarians of the period, and sometimes wrote that he thought the whole country would eventually become a Unitarian society. Jefferson recorded that the teachings of Jesus contain the "outlines of a system of the most sublime morality which has ever fallen from the lips of man." He added, "I am of a sect by myself, as far as I know."

Although his specific denominational and congregational ties were limited in his adulthood and his ever-evolving theological beliefs were distinctively his own, Jefferson was by his own admission, a progressive "Christian" if only in intent. He attended Episcopalian services as president, but his manipulation and rewriting of the Christian bible certainly speaks to a man who was both curious and conflicted. He once wrote, "I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished anyone to be..." This aspect of Jefferson's personal belief system remains among the most controversial and debated of all. Bible scholars have accused him of being both a genius and an atheist. Only the former is true.

Jefferson rejected the "divinity" of Jesus, but he believed that Christ was a deeply interesting and profoundly important moral or ethical teacher. He also subscribed to the belief that it was in Christ's moral and ethical teachings that a civilized society should be conducted. Cynical of the miracle accounts in the New Testament, Jefferson was convinced that the authentic words of Jesus had been contaminated.

His theory was that the earliest Christians, eager to make their religion appealing to the pagans, had obscured the words of Jesus with the philosophy of the ancient Greeks and the teachings of Plato. These so-called "Platonists" had thoroughly muddled Jesus' original message. Firmly believing that reason could be added in place of what he considered to be "supernatural" embellishments, Jefferson worked tirelessly to compose a shortened version of the Gospels titled "The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth." The subtitle stated that the work was "extracted from the account of his life and the doctrines as given by Matthew, Mark, Luke & John."

On April 21, 1803, Jefferson sent a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush, who was a fellow ‘Founding Father' and devout Christian, explaining his own interpretation of scripture.

Dear Sir,

In some of the delightful conversations with you in the evenings of 1798-99, and which served as an anodyne to the afflictions of the crisis through which our country was then laboring, the Christian religion was sometimes our topic; and I then promised you that one day or other I would give you my views of it. They are the result of a life of inquiry and reflection, and very different from that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed, but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished anyone to be: sincerely attached to his doctrines in preference to all others, ascribing to himself every human excellence, and believing he never claimed any other. At the short interval since these conversations, when I could justifiably abstract my mind from public affairs, the subject has been under my contemplation. But the more I considered it, the more it expanded beyond the measure of either my time or information. In the moment of my late departure from Monticello, I received from Dr. Priestley his little treatise of "Socrates and Jesus Compared." This being a section of the general view I had taken of the field, it became a subject of reflection while on the road and unoccupied otherwise. The result was, to arrange in my mind a syllabus or outline of such an estimate of the comparative merits of Christianity as I wished to see executed by someone of more leisure and information for the task than myself. This I now send you as the only discharge of my promise I can probably ever execute. And in confiding it to you, I know it will not be exposed to the malignant perversions of those who make every word from me a text for new misrepresentations and calumnies. I am moreover averse to the communication of my religious tenets to the public, because it would countenance the presumption of those who have endeavored to draw them before that tribunal, and to seduce public opinion to erect itself into that inquisition over the rights of conscience which the laws have so justly proscribed. It behooves every man who values liberty of conscience for himself, to resist invasions of it in the case of others; or their case may, by change of circumstances, become his own. It behooves him, too, in his own case, to give no example of concession, betraying the common right of independent opinion, by answering questions of faith which the laws have left between God and himself. Accept my affectionate salutations.

- Th: Jefferson

In 1820 Jefferson returned to his controversial New Testament research. This time, he completed a much more ambitious work titled "The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth Extracted Textually from the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French and English." The text of the New Testament appears in four parallel columns in four languages. Jefferson omitted the words that he thought were inauthentic and retained those he believed were original. The resulting work is commonly known as the "Jefferson Bible."

READ: The Jefferson Bible (online edition)

Clearly, religion played a major role in the intellectual life of Thomas Jefferson. Whether his views and practices failed to fit into a traditionally-organized Christian-Judea doctrine, his exhaustive examination, dissection, and authoring of religious studies prove that spirituality mattered to him. Therefore, for anyone to imply that his statute of freedom was created to stifle the practice of religion is completely illogical.

Thomas Jefferson was a believer. He absolutely believed in a higher power by referencing "the Creator." And he believed that everyone within America's borders deserved the right to believe and worship, or not believe and disregard. He also believed in the moral teachings of the one referred to as Jesus Christ, whether he was the Messiah or not. In a letter sent to Harvard Professor Benjamin Waterhouse in 1822, Jefferson stated, "The doctrines of Jesus are simple, and tend all to the happiness of man."

So it is entirely within reason to believe that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom to empower and protect believers and non-believers alike and not to impose restrictions on them. The key word to understanding this document is contained in its very title, "Freedom." Freedom was the most important attribute that the Founding Fathers wished to achieve. Freedom was the keystone in the foundation of the United States of America.

Freedom of religion meant that all people had an equal right to practice their spiritual doctrines without having to worry about the government challenging, or even limiting them.

In his mind, this free will of spiritual expression belonged to everyone including Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and what we would refer to in modern times as New Age practitioners. At the same time, Atheists and Pagans also shared in the very same freedom to either reject or pursue their own beliefs. Thanks to the foresight and brilliance of Thomas Jefferson and his contemporaries, we all have the freedom to believe or not; the freedom to attend church or not; and the freedom to pray or not.

To sanction or officially recognize a single faith (such as Christianity) would have not only been contrary to the Founder's intent, it would have marginalized a portion of society. This statute was all about inclusiveness. This means that all believers have the exact same liberties, regardless of the fact that their belief systems are completely opposed to one another. For example, the Christian is protected from the government mandating that he or she has to follow a particular denomination and the Atheist is protected from the government mandating that he or she believe at all. It's a brilliant and liberating concept when exercised in the manner it was intended.

The "common-sense" practice of uninhibited religious freedom continued until the late 20th-century when individual special-interest groups began to take offense to public religious practices and what appeared to be governmental sanctions of religious holidays. Many petitions appeared in court where groups of believers and non-believers alike argued whether the other side had any right to express their beliefs at all. This litigious conflict spilled out into the public square where religious symbology came under scrutiny. Public prayer and displays were removed in some sectors. Religious slogans and events were also contested.

Unfortunately, like many of our nation's principles, this one has been skewed, even corrupted at times, to imply that the "separation of church and state" means that all forms of religion cannot be celebrated and/or expressed within the public square. These misguided and ultimately petty arguments would no doubt irritate our Founders, especially Thomas Jefferson who fervently believed the opposite.

Here was an open-minded man who had the foresight to see a unified society, where people of different faiths lived secure in knowing that they all shared the same liberty to express their beliefs (or not) without worrying about the intolerance or interference of the government. The irony of this debate is that in challenging the spiritual beliefs of others, we have, as a country, inevitably stifled the very freedom that is granted to us by the "separation of church and state." Mr. Jefferson did not want his prized statute to result in the forced removal of all religious practices and references from the public square. He wanted it to allow all people the option to practice religion according to their beliefs, or not practice religion at all, because according to his own pen, "we all are endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable Rights," no matter who that Creator is, or is not, to us.

By Michael Aubrecht for The Jefferson Project, Nov., 2008

Monday, 13 June 2011

The Luckiest Guy

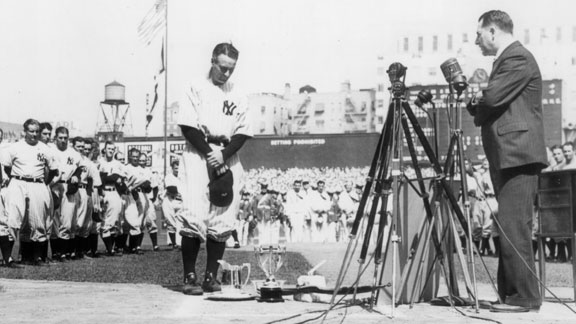

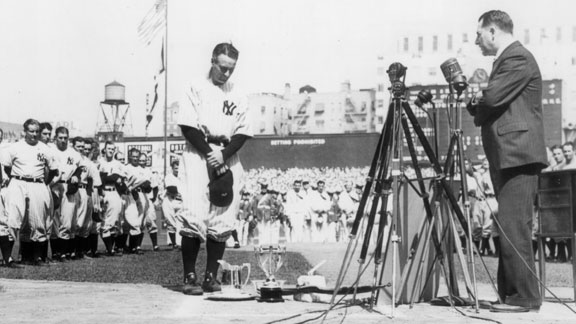

ABOVE: Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium, July 4, 1939.

Today’s post is a little 'off-topic' as it presents another one of my favorite genres of historical study, baseball. My first 'paid-gig' as a writer was that of a contributing historian for Baseball-Almanac.com (2000-2006). Next spring, Eric Wittenberg and I will debut our new book titled You Stink! Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players (The Kent State University Press). The anticipation that is already buzzing around this title is very much appreciated and I for one cannot wait to promote it. This past weekend I shared a rather lengthy, and in-depth conversation with a Red Sox aficionado who was willing to acknowledge that there was at the very least, one Yankee he admired. This one's for him...

Lou Gehrig’s performance on the field made him an American icon, but it was his tragic and untimely death that made him unforgettable. A real-life folk hero, Gehrig was everything a professional baseball player should and shouldn’t be. A quiet man who “carried a big stick,” Gehrig was a blue-collar champion. His records and statistics spoke louder than his actions and his career numbers still rank among the highest in the history of Major League Baseball. As a member of baseball’s most storied franchise, his accomplishments with the first Yankees dynasty are without question. His dedication to the game was certainly second to none, yet beyond baseball, there was nothing newsworthy or spectacular about him. In the words of his widow, Eleanor, “He was just a square, honest guy.”

Simply stated, Lou Gehrig was a baseball player…a great baseball player. All-Century Teammate, Hall of Famer, Triple Crown Winner, All-Star, World Series Champion, Most Valuable Player… these are just some of the terms used to describe the one they called “The Iron Horse.” Unlike the players of today, Gehrig spent his entire professional career with the same team while wearing the blue pinstripes in his hometown of New York City. His life story represented the “American Dream” and read more like a Hollywood movie script. Surprisingly more fact than fiction, it was appropriately translated into THE PRIDE OF THE YANKEES, which was nominated for eleven Academy Awards in 1943 and is still regarded by many today as the finest baseball movie ever made. His statistics spoke volumes as well and continue to prove that his impact on our national pastime remains second to none by a player from his era.

For starters, his lifetime batting average was .340, fifteenth all-time highest, and he amassed more than 400 total bases in five seasons. A player with few peers, Gehrig remains one of only seven players with more than 100 extra-base hits in one season. During his career he averaged 147 RBIs a year and his 184 RBIs in 1931 still remains the highest single-season total in American League history. Always at the top of his game, Gehrig won the Triple Crown in 1934, with a .363 average, 49 homers, and 165 RBIs, and was chosen Most Valuable Player in both 1927 and 1936. Unbelievable for a man of his size, #4 stole home 15 times, and he batted .361 in 34 World Series games with 10 homers, eight doubles, and 35 RBIs. Still standing is his record for career grand slams with 23. Gehrig hit 73 three-run homers, as well as 166 two-run shots, giving him the highest average of RBIs (per homer) of any player with more than 300 home runs. Not bad for a guy who originally entered Columbia University with the intention of becoming an engineer!

For most ballplayers, this would have been more than enough fare for a ticket to Cooperstown, but for Gehrig, the aforementioned stats are only a glimpse into his brilliant career. Still the only player in history to drive in 500 runs in three years, he also hit 493 home runs (while playing first), the most by any first baseman in history. On June 3, 1932, Gehrig became the first American Leaguer to hit four home runs in a game and he was the first athlete to have his number officially retired in 1939. A true thoroughbred, he was christened the “Iron Horse” when he held the “unbreakable” record of 2,130 consecutive games played, until 1998, when it was finally topped by another “Iron Man” named Cal Ripken Jr. A tireless worker, Gehrig played every game for more than 13 years despite a broken thumb, a broken toe and back spasms. Later in his career, his hands were X-rayed and doctors were able to spot 17 different fractures that had “healed” while he continued to play. This toughness could be attributed to the fact that he was the only surviving child (out of 4) of hard-working German immigrants. Somehow though, even his resilient exterior could not overcome the growing sickness he hid within.

Things began to change in 1938 as Gehrig struggled and fell below .300 for the first time since 1925. He appeared clumsy and sluggish on (and off) the field and it was painfully clear that there was something wrong. He lacked his usual dominant swing and many pitches that he would have normally hit out of the ballpark fizzled into meager fly outs. Initially, doctors diagnosed him with having a gall bladder problem and put him on a bland diet, which only made him weaker. Determined to work through his pain, he managed to play in the first eight games of the 1939 season, but fatigue weighed on his bat and he was barely able to field the ball. Gehrig knew that when his fellow Yankees had to congratulate him for stumbling into an average catch, it was time for him to leave. Eventually, he took himself out of the game and unfortunately, he would never return.

After a battery of tests, doctors at the Mayo Clinic diagnosed Gehrig as having a very rare form of degenerative disease called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The prognosis was terminal and there was no chance that he would ever play baseball again. Aware that his days were numbered, he continued to carry himself with unwavering dignity, despite being unable to conceal his failing health.

Local sports writer Paul Gallico suggested that the team should have a recognition day to honor Gehrig on July 4, 1939. In attendance were Mom and Pop Gehrig, Eleanor Gehrig (wife), and all the 1939 Yankees with manager Joe McCarthy. Other guests included Bob Meusel, Bob Shawkey, Herb Pennock, Waite Hoyt, Joe Dugan, Mark Koenig, Benny Bengough, Tony Lazzeri, Arthur Fletcher, Earle Combs, Wally Schang, Wally Pipp, Everett Scott, New York Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia, US Postmaster General James A. Farley, and the New York baseball writers dean and MC for the ceremony, Sid Mercer. Babe Ruth showed up late, as was his typical fashion, and drew a loud cheer from the crowd. Gehrig was touched that there were so many people there on his behalf, but he had mixed emotions about Ruth being there. The two, once good friends, had not spoken in years.

Gehrig historian Sara Kaden Brunsvold, recalled the ceremony:

During the first game, Gehrig stayed in the Yankee dugout anxiously awaiting the ceremony that would take place at home plate at the end of the game. Similarly Joe McCarthy was fretting over the words he would say to Gehrig during the ceremony. Neither man thought himself articulate, and neither looked forward to having so many eyes on them. Whereas Gehrig decided to do the best he could with the impending ceremony, McCarthy was so nervous he became irritable. But he still had presence of mind enough to notice how frail Gehrig looked, and he pulled some of the Yankees players aside and told them to watch Gehrig during the ceremony in case he should start to collapse.

Finally the first game was over and workers set up a hive of microphones behind home plate. The Yankee players of the current year and yesteryear lined up along the foul lines. Gehrig was placed near the microphones. A line of well-wishers from various occupations and fame came to the mics to say sweet, sweet things to Gehrig and about Gehrig. Some tears escaped from his eyes while he nervously, humbly hung his head and made a small circle of impressions in the dirt with his spikes. He took every word said to heart.

McCarthy came to the mics to say his piece with limbs trembling just as much as Gerhig’s. Despite his uneasiness, McCarthy was as heartfelt as he could manage, fighting the urge to bawl like a baby out of respect to Gehrig’s shaky emotions. Because McCarthy and Gehrig were very close, almost a father-son relationship, McCarthy knew that if he started crying it would probably make things that much worse for Gehrig trying to get through the ceremony. The most memorable part of his speech was when he assured Gehrig that no matter what Gehrig thought of himself, he was never a hindrance to the team.

Gehrig was given a number of presents, commemorative plaques, and trophies. Some came from the big-wig people; and, touching, some came from folks of the Stadium’s janitorial service and groundskeepers. The most talked about present Gehrig received was a silver trophy with all the Yankee players’ signatures on it presented by McCarthy. Inscribed on the front was a poem the Yankees had asked Times writer John Kieran to pen:

We’ve been to the wars together,

We took our foes as they came;

And always you were the leader,

And ever you played the game.

Idol of cheering millions;

Records are yours by sheaves;

Iron of frame they hailed you,

Decked you with laurel leaves.

But higher than that we hold you,

We who have known you best;

Knowing the way you came through

Every human test.

Let this be a silent token

Of lasting friendship’s gleam

And all that we’ve left unspoken.

- Your Pals on the Yankee Team

With more than 62,000 fans in attendance, Gehrig slowly stepped up to a bank of microphones and spoke those immortal words of thanks in one of the most heartfelt speeches ever given. As a testament to his courage and selflessness, he opened his remarks with the famous line, “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.”

He continued: “I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans. Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert - also the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow - to have spent the next nine years with that wonderful little fellow Miller Huggins - then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology - the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy! Sure, I’m lucky. When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift, that’s something! When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies, that’s something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles against her own daughter, that’s something. When you have a father and mother who work all their lives so that you can have an education and build your body, it’s a blessing! When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed, that’s the finest I know. So I close in saying that I might have had a tough break - but I have an awful lot to live for!”

His obituary, as printed in the New York Times, outlined his contributions to the community both on the baseball field and off:

...Regarded by some observers as the greatest player ever to grace the diamond, Gehrig, after playing in 2,130 consecutive championship contests, was forced to end his career in 1939 when an ailment that had been hindering his efforts was diagnosed as a form of paralysis. ...But as brilliant as was his career, Lou will be remembered for more than his endurance record. He was a superb batter in his heyday and a prodigious clouter of home runs. The record book is liberally strewn with his feats at the plate.

As a fitting tribute, Lou Gehrig was elected to the Hall of Fame that December. During the last months of his life, he worked on youth projects for New York until he was unable to walk. He died in 1941, at the age of 37. He was cremated, and his remains are in Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, roughly, 45 minutes from Manhattan. A headstone for Gehrig was erected that mistakenly claims he was born in 1905 (he was really born in 1903). His sudden death brought national attention to this relatively unknown affliction known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the illness has since been renamed “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”. His position in the public eye helped to inspire more intensive research and today the ALS medical community is hopefully getting closer to finding a cure.

The tragedy of his death still resonates today with baseball historians, players and fans all around the world. And it is important that we all remember that his contributions as a man far exceed those of a mere ballplayer. Lou Gerhig proved that anyone could achieve his or her dreams through hard work and determination. He then exhibited an iron-man work ethic that has only been broken once in the history of the game. Finally, he showed how courage and class could carry one through the most difficult of times.

Lou Gehrig accomplished more in his short life than most athletes could ever dream. He was a pure ballplayer at a time when the game was pure. As the years go by, so does the distance between young fans and the players of Gehrig’s era. Their game was timeless and we may never experience baseball as it was experienced back then.

EXTRA: Lou Gehrig's Lifetime Statistics at Baseball-Almanac.

Saturday, 11 June 2011

The Gallant Boys of the 123rd PA Vols.

Thursday, 9 June 2011

Keeping with our recurring art theme

Of all the bullets on my resume, perhaps none make me prouder than my side-job as the personal copywriter for renowned Civil War painter Mort Kunstler. I got this cherry-gig after I penned a few articles on the artist for The Free Lance-Star here in Fredericksburg, VA (feature). After 3-years together, I am now coming up on what will be my 10th piece (sample) and I can’t wait to see what my friend will paint next. Although Mort has spent the last two decades focusing on the Civil War, he has done some excellent pieces on the Revolutionary War period over the course of his extraordinary 40+year career. This includes paintings from his The American Spirit series. Here is one of my favorites:

World Turned Upside Down (Yorktown, Va., October 19, 1781)

Finally, they had won. After more than six years of warfare, the War for Independence was ending – and it was an American victory. So many times the cause of American freedom had seemed lost. So much hardship had been borne by these Continental troops, and so often General George Washington had kept them in the war equipped with little more than determination. Now, aligned before them was the fearsome British army that had been sent to conquer the South – the army that had won so many victories in the Carolinas and had inflicted so much suffering on American civilians. Now these troops in red uniforms – composing perhaps the finest army in the world – were laying down their arms in surrender. And standing victorious before them were America’s citizen soldiers – “contemptible, cowardly dogs,” a British commander had once erroneously and ironically called them.

Led by General Washington and strengthened by a French army under General Comte de Rochambeau, these Continental troops had trapped General Charles Cornwallis and his British army with their backs to the water at Yorktown, Virginia. Washington had led a forced march from New York to the Virginia coast, and had taken the British by surprise. A French fleet had defeated the British navy at the nearby battle of the Capes – ending all hope of rescue for Cornwallis. The British had been battered into submission at Yorktown by a five-day artillery bombardment and repeated attacks by the Americans and the French. Finally, Cornwallis admitted defeat, and surrendered his army to the Americans he had so underestimated – but he could not bear to do it in person. He officially claimed to be ill, and sent a substitute, General Charles O’Hara, to perform the humiliating task. O’Hara offered the surrender sword to General Rochambeau, who recognized the intended insult, and pointed him toward General Washington. The General refused as well, and directed the British substitute to a subordinate, General Benjamin Lincoln.

And so it ended. Other British troops were in the field – a huge army in New York – but the surrender at Yorktown was humiliation enough, and King George III agreed to give up the American colonies he had once vowed to subdue. As Cornwallis’ defeated army marched to the surrender, a British band played a contemporary tune entitled “The World Turned Upside Down.” It was more appropriate than even they realized: American independence would launch a freedom movement that would topple tyrants for generations to come and would inspire oppressed peoples throughout the world to a “new birth of freedom.”

Mort Kunstler’s Comments:

In the fall of 2005, the U.S. Army War College’s Class of 2006 Gift Committee asked me if I would be interested in a commission to paint the surrender at Yorktown. To be able to accurately paint an event of such enormous importance was a wonderful opportunity. I’ve had an interest in this subject for a long time. Back in the 1970s, I did two small paintings on the surrender, and since I always wanted to do a major painting on the subject, I accepted the commission. I contacted Diane Depew at the National Park Service in Yorktown and John Giblin of the Army War College to help with the details.

“The World Turned Upside Down” places the Continental troops on the left with their artillery in the foreground. This is the way the scene would have looked to a British soldier standing in the road, waiting to march between the line of American troops, and French troops seen in the right background. It’s a different perspective from earlier artworks of the topic – and one that I think gives us a fresh view of this pivotal historical event.

The commander of Washington’s French allies, General Rochambeau sits astride his horse on the extreme right, with the flags of his Soissonnais Regiment fluttering above him. To his left, Washington’s aide, General Benjamin Lincoln – mounted on his grey charger – accepts the surrender from British General Charles O’Hara. General George Washington, is seen mounted to the left of his personal headquarters flag, the blue banner with the white stars. The flag with the unusual arrangement of red, white and blue stripes seen immediately to the right of Washington’s flag is a well-documented early American flag of the period.

The helmeted troops on General Washington’s right are the elite Life Guard, who served as the general’s personal guard. After the surrender ceremony, the British had to march a mile and a half to finally lay down their arms at what became known as “Surrender Field” – now a national historic site. Although the Yorktown region had been drenched with torrential rains two nights earlier – as indicated by the puddle in the foreground – the day of the surrender was described as a beautiful, clear day with lots of white, puffy clouds. The puddle is also used as a design element, to act as a pointer that guides the viewer to the painting’s center of interest – General O’Hara offering the sword of surrender to General Lincoln.

I really enjoyed painting “The World Turned Upside Down” – it was a nice departure from the usual Civil War subjects I have been doing and I hope it proves to be a long-lasting reminder of our hard-won American freedom.

More related paintings:

The Capture of Fort Motte

Benedict Arnold Demands the Powderhouse Key

Washington at Carlisle

Digging the Trenches at Yorktown

Lafayette With Washington at Morristown

Monday, 6 June 2011

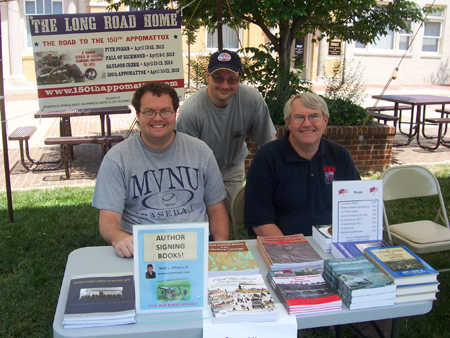

Gathering of Eagles 2011

On Saturday (June 4th) I had the privilege of participating in the Annual Gathering of Eagles at the historic Old Courthouse Civil War Museum in Winchester Virginia. This one-of-a-kind event offers a weekend filled with the foremost impressionists of leaders and politicians from both sides of the Civil War. This was my fourth appearance in six years and although the crowds were a bit slimmer due to the economy, everyone had a great time.Coinciding with the Civil War Sesquicentennial, this year’s theme was 1861, the “Gathering Storm.” The hosts, Lee’s Lieutenants and the Federal General’s Corps, delivered incredibly unique performances that focused on the period leading up to the war. It was neat to see all of the Confederate Generals dressed up in their blue U.S. Army uniforms when performing the scenes that took place prior to secession. Some of the performances included a re-enactment of the two president’s inaugural addresses, an emotional piece that dealt with the separation of friends, a discussion over the issues of loyalty and traitors, and the always popular “Meet the Generals.”

I had the privilege of sharing the Author’s Tent with some outstanding historians including Jerry Hilsworth, author of Civil War Winchester and Scott Mingus Sr. (and his son) author of Flames Beyond Gettysburg and about 6 other titles. I really enjoyed the opportunity to get to know these guys who are all experts in their field of study. Jerry’s knowledge of Winchester’s wartime experiences, especially off of the battlefield, was tremendous and Scott’s expertise on regiments like the Louisiana Tigers blew me away. Scott’s son, a professor from Liberty University, and I shared some great conversations on the state of Major League Baseball.

This year I focused on selling DVDs in place of my books. Despite being an outdoor event, I managed to run electricity and set up our usual display with movie props, promo materials, a behind the scenes kiosk, and the film playing on a small screen. This enabled me to share the story of Richard Kirkland with a diverse group of people who were coming in and out of the re-enactor events. I spoke to several college kids, members from a kid’s soccer team, retired folks, Civil War buffs and an elementary school librarian. My parents even came by on the way home from Gettysburg.Everyone was very receptive to Kirkland’s story and asked great questions. The one comment I got repeatedly was that folks were familiar with the monument in Fredericksburg, but never knew the story behind it. Every time I hear that it reinforces how important this story is and how thankful I am to be part of this movie. One of the biggest joys for me as the producer is the opportunities that I get to meet people. Over the last year we have screened the The Angel of Marye’s Heights in Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, Stafford, Lexington, Lynchburg, Pittsburgh, Manassas, Winchester, Arlington, Savannah, Columbia and Brunswick. The Angel is also being shown (and sold) at multiple museums and used in history classrooms from New York to California. People from almost every state have purchased a copy of the DVD and we even have some international sales. The buzz keeps growing and growing.

This past weekend was the cap on a year that has reinforced the idea (for me) that doing this stuff really matters. Whether it’s writing a book, attending a re-enactment, producing a documentary, or simply talking to people, those of us that have dedicated a portion of our lives to preserving and presenting the history of our nation are doing a great service to the memories of those who came before us. This is proven by the people we meet, who validate our efforts and make all of this worth it.

Newer | Latest | Older

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...

As the argument over America being founded as a Christian nation has been a recurring topic...