Guest Post

One of my favorite aspects of hosting this blog is the opportunity it gives me to showcase the work of talented historians who do not have blogs of their own. Over the last few months I have been corresponding with several writers who all share a common interest in the Colonial/Revolutionary Period. All of them have submitted articles to Patriots of the American Revolution and are conducting some highly original studies into our Nation's fight for independence. I have invited each of them to appear on ‘Blog or Die’ as guest posters and today I would like to share the first of these. Our inaugural guest blogger is Michael J. Kahn, a NY Police Officer, Board Trustee for the Yorktown Historical Society and leader for the Pines Bridge Monument.

A Monumental Effort: The 1st RI at Pines Bridge

by Michael J. Kahn

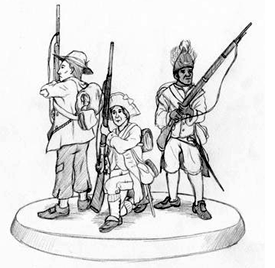

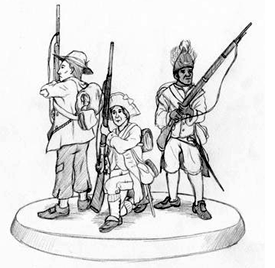

I would like to share a project that I am working on in my hometown that would honor a unique Continental regiment and their commander who were “massacred” at the hands of Tories. It is my goal to have a monument to erect three statues commemorating those soldiers and officers of the First Rhode Island Regiment.

Colonel Christopher Greene and several soldiers under his command died in an ambush attack on May 14, 1781 just north of the Croton River (in modern-day Yorktown Heights, NY). His regiment was an integrated unit, comprised of whites, African Americans, and Native Americans. This skirmish (known locally as the Battle of Pines Bridge) involved Loyalist troops under the command of Colonel James DeLancey, the unit known as the DeLancey's Refugees (or Cowboys). The African Americans that were captured alive were sold into slavery in the British West Indies.

These men and their assigned duties have not been totally lost to history, but they have yet to receive, in my opinion, their due respect and admiration. The Pines Bridge was a vital strategic crossing point of the Croton River, a river that links New England directly with the Hudson River. We all know the significance of the Hudson during the war, but the Croton River almost never gets the appropriate mention. Washington knew that control of the Croton River mean three things: a natural barrier, it allowed for a defense from incursions from southern Westchester County and New York City; the river also established a staging point for a potential re-conquest of Manhattan Island; and the Croton allowed for trade and communication to flow between New England and the Middle Colonies.

The theme of the monument is to reflect the diversity of the regiment and how different people came together to fight for a common glorious cause. Each statue would represent the three cultures involved, and would ideally be placed near the current Pines Bridge.

The theme of the monument is to reflect the diversity of the regiment and how different people came together to fight for a common glorious cause. Each statue would represent the three cultures involved, and would ideally be placed near the current Pines Bridge.

This project has received a lot of local political support, as well as interest of Congressman Jim Langevin's office (2nd Congressional District, RI). The local media as well as the Rhode Island media have contacted me to follow the project's progression. We have also partnered with our town planning department as well as our local chamber of commerce. (Pic: Artist Paul Gioacchini’s rendering of the monument.)

Additionally, NY State Senator-Elect Greg Ball and Congresswoman-Elect Dr. Nan Hayworth have pledged their assistance and shown interest, respectively, to seeing this undertaking through to completion. The President of the Putnam County/Westchester County Sons of the American Revolution, Ken Stevens, is also attached to this project. Furthermore, I will be speaking about this project to local chapters of the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution this month.

I’m hoping that many more people will come out to support this project, both politically and financially. The committee charged with the task of bringing this project to fruition is working diligently on getting it done by May 14, 2012. We just finished a site plan and are applying for the necessary permits to place the statue at the chosen location.

Anyone wishing to make donations towards the funding of the monument may send a check made out to the Yorktown Historical Society with “monument fund” written on the memo section of the check. They can be mailed to the Yorktown Historical Society, PO Box 355, Yorktown Heights, New York 10598. The Yorktown Historical Society is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and all donations are tax-deductible.

BIO: Michael J. Kahn is a police officer for the Town of Yorktown, New York and a Board Trustee for the Yorktown Historical Society. He is the project leader for the Pines Bridge Monument and can be reached at Monument1781@yahoo.com.

Posted by ny5/pinstripepress

at 1:03 PM EST

Updated: Wednesday, 17 November 2010 1:32 PM EST

Permalink |

Share This Post

This one's for Jana (again).

This post was deleted when I approved the comments. It appears that the moderator function is not working properly. At the risk of losing another post, I have temporarily turned off the comments option until it is fixed. Here is the repost:

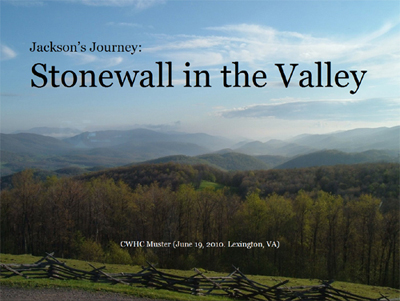

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

This is an extra special thrill for me as I finally get an opportunity to meet and greet a roomful of friends, many who I have known only in the realm of cyberspace. I want to thank Pat and Steve for the invite, as well as the folks here at the Holiday Inn Lexington for thier hospitality. To be invited to give the annual CWHC Muster Banquet address is an exceptional honor, and when you throw in a free meal, well it doesn’t get any better than this. As most of you know I switched over to the era of the Revolution last year and tonight will likely be my last new Civil War talk. As bittersweet as that sounds, I can’t think of a better audience to share it with. I am also very thankful that we get to debut our new documentary film on Richard Kirkland tonight and look forward to your reactions. We are taping this to post online for Pat, Steve and Jana and those who could not be here. Hello friends we miss you. Tonight I hope to share some insights into what I consider to be one of THE most noteworthy and understated campaigns of the entire war.

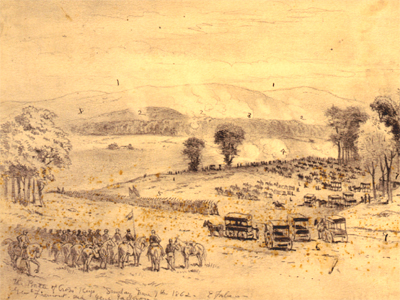

Over the last few days you have visited the sites and scenes of many of the area’s most hallowed grounds and hallowed halls. You have been to Cross Keys, Port Republic, and New Market. You have visited historic VMI and Lee Chapel. You have no doubt gained a deeper understanding of the participants in the Valley Campaign and their experiences both on and off the battlefield.

As a result I don’t want to stand up here and regurgitate a bunch of facts that you have learned over the course of this trip. Tonight I want to share something different. I want share some of the lesser known stories from the first Shenandoah Valley Campaign. I will also be using some rare images that may be unknown to you in place of the standard portraits.

Now I will be the first to admit that my longstanding affection for the life and legacy of Thomas Jackson is perhaps one of the biggest keystones in my foundation as a public historian. My first book was titled Onward Christian Soldier, I taught an 8-week bible study class on Jackson’s piousness at Spotsylvania Presbyterian Church, my license plate says STOWNWL and most recently, the newest member of the Aubrecht brood was named Jackson. OK I like the guy.

That said... I have grown far more critical in my analysis over the years. I like to think that I have matured as a historian and therefore, come to realize that while Thomas Jonathan Jackson was a tremendous leader and an inspiration to those around him, he was not infallible, nor perfect by any stretch of the imagination. He was not a god, he was simply a man. Still worthy of our attention - but not beyond our reach.

Great soldiers, especially great officers, are held in high regards by those who fought under them and this affection influences how their stories were recounted and thus how they are remembered today. Even these titans of military history made mistakes and they are far too often guilty of receiving sole credit for the success of others - albeit unintentionally.

It was while preparing for this speech that I came to realize that as tenacious as Jackson was during his time in the Valley, as many successes he had on the field, he also made mistakes and cost lives. He was stubborn and at times, let his own personal convictions influence his decisions. This was not always in the best interests of his men. Jackson was brilliant, but secretive and this hampered the trust between him and his officers. This revelation of imperfection makes the good general more human in my eyes and in some cases even more worthy of our study.

More importantly, by taking Jackson down off this pedestal, it reinforces the notion that his men were the ones whose blood, sweat, and tears enabled him to rise to such heights. In other words the story of Stonewall in the Valley is much bigger than just Thomas Jackson. Its all about the men. Caesar would not have risen if not for the 13th Legion, nor Washington without the Continental Army, nor Patton without the 3rd.

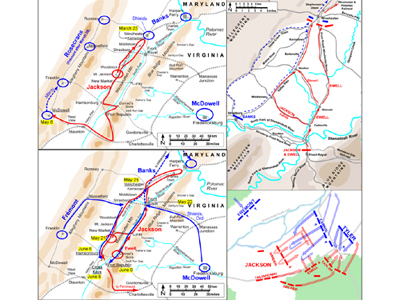

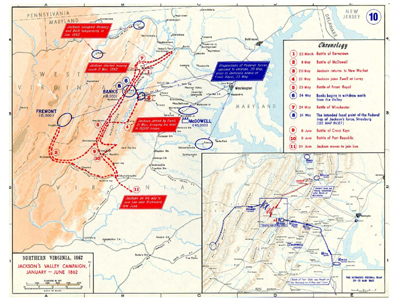

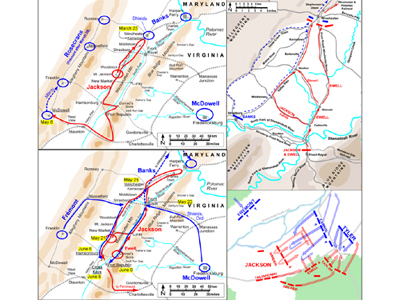

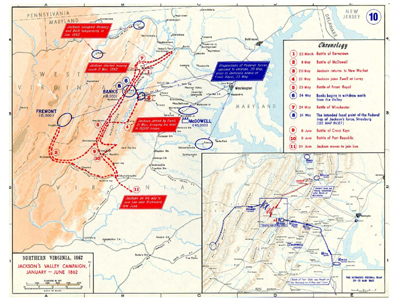

When examining the Valley Campaign of 1862, it is hard not to be immediately struck by the numbers. Let me quote a few from my book: “In May of 1862, Jackson’s troops took part in what is still considered one of the most brilliant and successful missions in American military history, the Shenandoah Valley Campaign. During that time over seventeen thousand Confederates marched more than six hundred miles to participate in four major battles and seven minor engagements. When it was over, Jackson’s troops had defeated four sizable Union armies while capturing nine pieces of artillery, ten thousand small arms and four thousand prisoners.”

That’s some impressive stats for sure. And it goes without saying that General Jackson was an aggressive commander. His brilliance of strategy and courage on the battlefield were exhibited at every engagement that he participated in from First Manassas to Chancellorsville. Attack–Attack was his tactic of choice. This campaign however, challenged him on a variety of levels. The length and distance at which these fights were spread was extraordinary and the energy that was expended just getting from one fight to another is startling. Maintaining an offensive approach to battle was not always the best directive in the Valley Campaign. Determination and discipline was.

Southern troops marched 646 miles over the course of 48 days. They were also outnumbered by the thousands. Stonewall’s command, the Valley District of the Department of Northern Virginia, started with a force of a mere 5,000, and would eventually peak of 17,000 men. The Union armies (yes that is plural) opposing it numbered at around 52,000 men. So even at its peak, Jackson was lagging behind the enemy by 35,000 men.

Although they would emerge from this campaign victorious, the Confederate forces did not start off that way. The opening battle is still considered to be Jackson’s first and only true defeat of the war. And regardless of who has been blamed over the years, the responsibility ultimately rests with the senior commanding officer.

The Battle of Kernstown was fought on March 23, 1862, in Frederick County and Winchester, Virginia. It was the opening melee and in retrospect remains a perfect example of how poor intelligence and arrogance can doom an army. After being assigned the task of tying down the Federal forces that were in the Shenandoah Valley, Jackson was informed that a small detachment of Northern troops under the command of Colonel Nathan Kimball was ripe for the picking.

Unfortunately for Jackson, this force was not a vulnerable underdog, but a full infantry division that outnumbered his ranks by two to one. His initial tactic was textbook and he sent in his cavalry to instigate an attack. Remember Jackson was a VMI Professor trained at West Point. He may have fought like a lion, but he thought like an officer. Under the command of Turner Ashby, Jackson’s horse soldiers were summarily pressed back. When the general sent a small detachment of infantry in support of his mounted troops, they also failed. At the same time Jackson planned to envelop the enemy with two other brigades. This proved to be a major mistake.

His intentions were based on bad information that had been leaked by southern loyalists and a miscalculation of opposing forces. As a result, Kimble and Col. Erastus Tyler's brigade were able to divide and drive the rebels from the field. In retrospect, exhaustion may have also played a part in this action. Jackson's orders from Johnston were to prevent Union forces from leaving the Valley, which it appeared they were now doing. After receiving word of Kimble’s men, Jackson turned his own men around and, in one of the more grueling forced marches of the war, moved northeast 25 miles on March 22 and another 15 to Kernstown on the morning of March 23. So these guys were literally hiking marathons and going straight into the fight. In the end Union casualties stood at 590 to the Confederate’s 718. Damaged pride and disgruntled officers were also a southern casualty of this engagement.

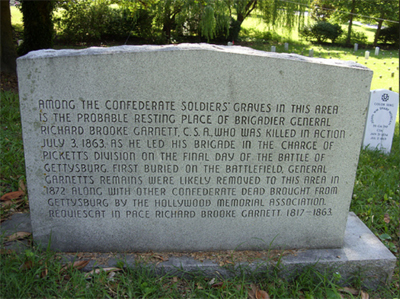

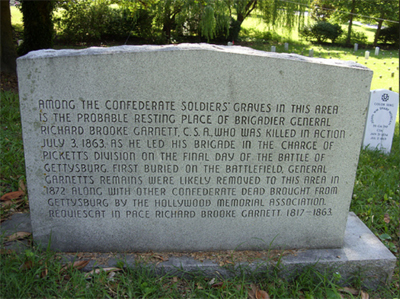

After Kernstown Jackson arrested the commander of his old Stonewall Brigade, Brig. Gen. Richard Garnett, for retreating from the battlefield before permission was received. Garnett would suffer from the humiliation of his court-martial for over a year, until he was finally killed in Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg in July of 1863. Now I know that we are all BIG fans of “THE movie” and the infamous scene in Gettysburg which Garnett rides his horse onto certain death is absolutely true. My personal belief was that he was not only nursing a sore leg, but also trying to save his reputation. This notion makes his demise all the more tragic.

Peter Cozzens, who is the author of a very balanced book on this subject titled Shenandoah 1862, wrote in defense of Garnett and I quote: “Seldom during the Civil War was a general officer as gallant and as capable as Garnett treated so unjustly.... By any objective standard, Garnett had done the best at Kernstown that could reasonably have been expected under the circumstances as they existed. Ignorant of Jackson’s tactical blueprint, his brigade out of ammunition and outflanked, Garnett took the only sane course of action. In doing so he saved the Valley army.”

After Kernstown Jackson withdrew his troops to Mount Jackson and this is where I get to talk about the extraordinary work of my favorite unsung hero of the Civil War, Capt. Jedediah Hotchkiss. Jed was an educator and an extremely gifted cartographer and topographer. He was also a northerner by birth. Many people do not know that Hotchkiss was born in Windsor, New York. He graduated from the Windsor Academy and, by the age of 18, he was teaching school in Pennsylvania. In 1855 Hotchkiss and his brother Nelson opened a school in Virginia. So he was a Yankee transplant.

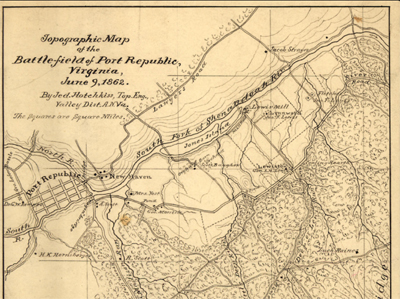

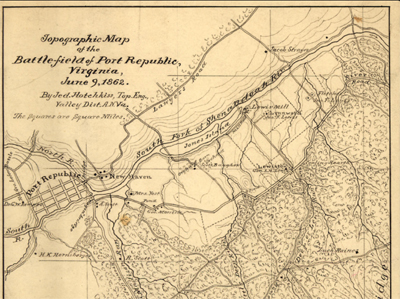

In late March of 1862 Jackson realized that he was ignorant of the landscape that lay before him. The area was too vast and spread out for him to properly direct movement. So he summoned Capt. Hotchkiss and gave him the following orders: “I want you to make me a map of the Valley, from Harpers Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offense and defense.”

According to Jed’s bio: “Running 150 miles in length and 25 miles wide, it was a daunting task, but Hotchkiss accepted the assignment, and worked on the map for the remainder of the war. In order to accommodate his large scale of 6,666.67 feet per inch, he glued together three portions of tracing linen to form a large singe map of 8.25 feet by 3.5 feet, with a three-quarter-inch grid. His map remained unsurpassed in accuracy and detail until the United States Geological Survey published topographical quadrangles later in the nineteenth century.” Now these were more than pretty pictures. Jed’s maps were tactical tools that Jackson exercised profusely. In fact, historians today give Hotchkiss credit for contributing to Jackson’s success in the Valley. I would like to add that Kernstown Battlefield Museum has some excellent examples of his maps that are relevant to this campaign.

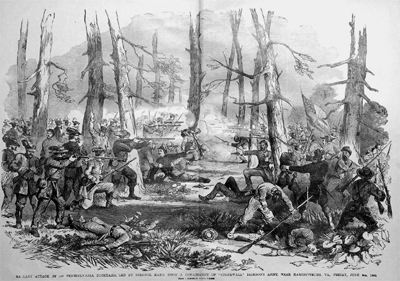

Now during this time Gen. Garnett was not the only soldier to be on Jackson’s list. The “Black Knight” himself Turner Ashby was under scrutiny for his poor intelligence gathering prior to Kernstown. His superior removed 10 of his 21 cavalry companies and reassigned them to Charles S. Winder, Garnett's replacement in command of the Stonewall Brigade. Winder mediated between the two officers and the stubborn Jackson uncharacteristically backed down, and restored Ashby's command. Of course like Garnett, Ashby would also be killed in combat. On June 6th Ashby’s men were attacked by the 1st New Jersey Cavalry at Good's Farm near Harrisonburg. Ashby had his horse shot out from under him and as he charged ahead on foot he was shot through the chest and died instantly. Now members of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserve (the Bucktails) took credit for the kill, while others said it was friendly fire. Ironically Ashby had just been promoted to brigadier general 10 days earlier. Ashby’s loss was severe, but of course he would be eclipsed both on the field and in the history books by the cavalier JEB Stuart.

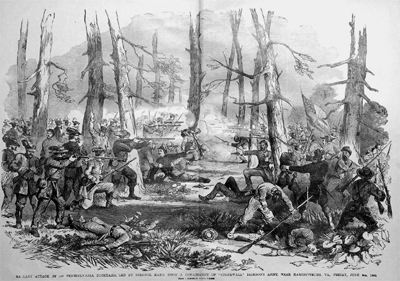

Shortly before the next engagement, the Battle of McDowell, Jackson combined his forces with those of Gen. Allegheny Johnson. When the opposing Union generals realized that they were outnumbered by the 10,000 men that the Confederates commanded, they made a pre-emptive attack. After the first Federal attack was repulsed at a place called Sitlington Hill, the Union troops regrouped made another assault on the Georgia lines. These men were the only non-Virginians on the battlefield.

It is said that they defiantly refused to withdraw in the face of superior numbers. One GA private wrote, “We did not come all this way to Virginia to run before Yankees.” By the end of the day, the 580 Georgians had suffered 180 casualties. This was 3 times more than any other regiment. Union casualties were 259, while the total Confederate losses were 420. It was one of the rare cases in the Civil War where the attacker lost fewer men than the defender.

The next engagement echoed scenes from my favorite John Wayne movie “The Horse Soldiers”. On May 23rd Ashby’s troops forded the Shenandoah River and set out to capture a Union depot and railroad trestle at Buckton Station. After defeating 2 companies of Federal infantry they burned the depot’s structures, tore up railroad track, and cut the telegraph wires, isolating Front Royal. Jackson then marched towards the town.

The center of Jackson’s line of battle was the ferocious Louisiana Tigers battalion (150 men under Ewell’s division), commanded by Col. Wheat. Of course Wheat’s Tigers wore distinctive uniforms similar to the French Zouave. As they attacked the Federals began to retreat and Jackson missed a tremendous opportunity to inflict major damage. His beloved artillery was delayed in arriving and Ashby’s cavalry was late in informing them of Jackson's orders.

That said the retreating Union troops were forced to halt and make a stand at Cedarville. It was there that some of the most lopsided casualties would occur in the entire war. Union casualties were 773, of which 691 were captured. Confederate losses were a mere 36 killed and wounded. Jackson’s men also captured about $300,000 of Federal supplies. The next two battles, one at Winchester and the other at Cross Keys resulted in some of the most insubordinate behavior of the war.

At the battle of Winchester, Jackson’s troops pursued the fleeing Federal forces who were headed south down the Valley Pike. Our friends the Tigers came upon a wagon train and instead of continuing to chase the Yankees, they stopped to loot and pillage the supplies. Jackson had also ordered his cavalry and artillery to move north in order to harass the Union troops on the other side of town, but many of Ashby’s men had found a wagon train of their own and proceeded to get drunk on Federal whiskey.

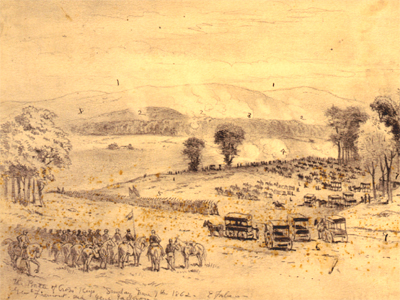

Jackson was extremely frustrated with the ineffective pursuit and later wrote, “Never was there such a chance for cavalry. Oh that my cavalry was in place!” As a result the Federals fled relatively unimpeded for 35 miles in 14 hours and lived to fight another day. Those two days would come in the form of the battles of Cross Keys and Port Republic with the first fight taking place on June 8th and the next on the 9th.

These were the decisive victories in Jackson’s Valley Campaign that ultimately forced the Union armies to retreat while leaving Jackson free to reinforce Gen. Robert E. Lee for the Seven Days Battles outside Richmond. The biggest factor to know about Cross Keys was that the southern troops were outnumbered 11,500 to 5,800 – BUT the northern troops believed the opposite to be true. Therefore they fought cautiously when they likely could have overwhelmed the rebels.

Port Republic was another story and most military historians agree that Jackson had poorly managed this engagement. This makes his victory all the more curious. In failing to properly deploy his men, Port Republic was the most damaging to the Confederates in terms of casualties. They lost 816 against a force one half their size (about 6,000 to 3,500). Union casualties were just over 1,000, with a high percentage representing prisoners. Once again I’d like to call on Historian Peter Cozzens who blames Jackson’s piecemeal deployment of troops for his heavy losses and argues that it was a battle that did not need to have been fought.

Despite this, following the Battle of Port Republic, the Union armies fled the Valley and Stonewall Jackson became the most celebrated soldier in the entire Confederacy. In a classic military campaign of surprise and maneuver, he had accomplished his difficult mission, driving the Yankees from Shenandoah soil and causing Washington to withhold over 40,000 troops from McClellan's offensive.

Military historians Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, summed up Jackson’s success in their study titled How the North Won. They wrote: “Always outnumbered seven to three, every time Jackson engaged he fought with the odds of about four to three in his favor—because, moving rapidly on interior lines, he hit fractions of his enemy with the bulk of his own command. ... Jackson enjoyed the great advantage that the northerners remained widely scattered on a perimeter within which his troops could maneuver to concentrate against first one and then another of the Union forces. Lincoln managed very well, personally maneuvering the scattered Union armies. Since neither Lincoln nor his advisers felt that Jackson’s small force could truly threaten Washington, they chose an offensive response as they sought to exploit their overwhelming forces and exterior position to overwhelm his army. But Jackson's great ability, celerity of movement, and successful series of small fights determined the outcome.” So despite having moments of mediocrity and imperfection, Jackson’s actions were commendable and his reputation as a fierce and uncompromising warrior was validated through this campaign. Southerners everywhere cheered when word arrived that the Yankee invaders had been driven from the Valley. Jackson of course got all the credit and he understandably became a household name. A Confederate Army nurse named Kate Cummings summarized this newfound national love-affair in her diary when she wrote: “A star has arisen: his name [Stonewall], for four weeks he has kept at bay more than one of the boasted armies. He is our protector”

Jackson himself, a devout religious man, gave credit in his own way. At a moment during the final battle in which his buckling troops were saved by reinforcements arriving in the 11th hour, Jackson turned to Ewell and said “General, he who does not see the hand of God in this is blind, sir, blind.”

In May of 1863 Jackson would be accidentally shot by his own men at the Battle of Chancellorsville forever etching his deity-like status in military lore. The 1862 Valley Campaign would go on to become a much studied example of brilliant maneuvering and is now taught at the same military schools in which Jackson attended and taught.

Perhaps the most worthy example of the lasting legacy of Jackson and this campaign comes from Howard Tanner in his excellent book Stonewall in the Valley. This account recalls the bond and memory of the men, who fought and bled together under their beloved commander. They are the ones whose legacy is far too often forgotten.

Tanner writes of an 81-year old man that is lying in his death bed, unconscious and unable to speak. One day there is an unexpected knock at the door and when the son answers it he sees an elderly gentleman standing on the porch. The old man asks to see his ailing father and the son informs him that he is unable to communicate. He says, “It will not be of much comfort to you and none to him.” The visitor interrupted and said “I fought with him at Port Republic. There were 23 of us then and few of us now.” Tanner adds: No more needed to be said. “If any of you wish to see him,” the son added, “You have certainly earned the right to do so.”

It is the bond these men shared that kept alive the enduring legacy of Stonewall in the Valley. They are all equal partners in Jackson’s Journey regardless of rank. And it is our job as historians and enthusiasts to see that they are never forgotten. Thanks to groups like yours - and weekends like this – their stories will remain for future generations. Thank you.

The theme of the monument is to reflect the diversity of the regiment and how different people came together to fight for a common glorious cause. Each statue would represent the three cultures involved, and would ideally be placed near the current Pines Bridge.

The theme of the monument is to reflect the diversity of the regiment and how different people came together to fight for a common glorious cause. Each statue would represent the three cultures involved, and would ideally be placed near the current Pines Bridge.

This weekend’s Civil War Author’s Day at

This weekend’s Civil War Author’s Day at

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.

Last week I received an email asking me to share the transcripts from my talk “Jackson’s Journey: Stonewall in the Valley,” which I delivered at the CWHC 2010 Muster Banquet on June 19, in Lexington, VA. That was also the event where we ran the test screening of “The Angel of Marye’s Heights”. Both presentations were a lot of fun to do and the audience was outstanding. Today I would like to share that speech and dedicate it to the memory of Ms. Jana Beaverson. Jana was a longtime member of the CWHC and a wonderful woman with whom I shared many online conversations with. She was unable to attend this event as she was undergoing chemotherapy. Jana passed away on October 9. It was my privilege to know her.