Inspiration in "Charm City"

Today I had the pleasure of traveling to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, where I dined on crab cakes in the shadow of the USS Constellation. Constructed in 1854, this vessel is known as a “sloop-of-war” and was the flagship for the U.S. African Squadron from 1859-1861. During this period she disrupted the African slave trade by interdicting three slave ships and releasing over 700 imprisoned Africans. Armed to the teeth, the Constellation boasts 16 × 8 in (200 mm) chambered shell guns, 4 × 32-pounder (15 kg) long guns, 1 × 20-pounder (9 kg) Parrott rifle, 1 × 30-pounder (14 kg) Parrott rifle, and 3 × 12-pounder (5 kg) bronze boat howitzers. Based on a 1797 frigate design, the USS Constellation was a Civil War–era ship.

I was so inspired by my visit, I am now working on a special post about “The Father of the American Navy,” John Paul Jones. Of all the officers that I have examined from the Revolutionary War, Jones ranks among the top of the list. His performance under fire is considered by many to be second to none and his tactics are still taught by the U.S. Navy today. Captain Jones also has family ties here in Fredericksburg and some of his relatives are buried here. Everyday on the way to the train station I walk past the corner of Lafayette Blvd. and Caroline Street, where a beautifully restored row house stands that belonged to Jones's brother, William Paul. Perhaps I will make some time to stop there one day and discuss the property’s legacy with its owner. Stay tuned for that JPJ post and be sure to visit the USS Constellation the next time you find yourself in Baltimore, craving crab cakes.

On a side-note, please look for my article in this Saturday’s Free Lance-Star Town & County on Mort Künstler’s newest release, The Angel of the Battlefield, as well as the release of my histiography written for the painting itself which depicts Clara Barton’s experience at Chatham. This will be the fourth FLS article I’ve penned on Mort and the fourth painting copy I’ve penned for Mort. He will be coming to town on the 20th for a print signing and I’ll be sure to take some photos to share with you here.

(Photograph by me, via BlackBerry)

The emancipating slaveholder

ABOVE: Life of George Washington--The farmer. By Junius Brutus Stearns (Library of Congress).

As my newfound studies into the Revolution continue to expand, one subject that has caught my attention is the extraordinary life and legacy of George Washington. Most of my current reading has been done in preparation for my upcoming presentation on Mary Ball Washington for the VA Farm Bureau Women’s Convention, and for an article that I am writing for Patriots of the American Revolution magazine on Col. Washington and the VA Militia’s experiences in western Pennsylvania. Sources for these projects include Edward G. Lengel’s General George Washington and Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer. Both of these titles are excellent and I am gaining a tremendous wealth of knowledge on our nation’s first commander-in-chief.

Over the years, the majority of my work has focused specifically on the social, political, and religious aspects of our collective history. That is to say NOT the military ones. I have zero expertise in battlefield tactics and leave that subject up to real military historians like Eric Wittenberg and Brooks Simpson. In lieu of manly weapons and strategy, I have chosen to tackle the equally explosive issue of race. Just as my book on Fredericksburg’s churches and PAR feature on Race and Remembrance at Monticello dealt with the complexities and contradictions of slavery, so too are my latest studies into the Founding Fathers. I have written extensively on Thomas Jefferson’s attitudes on the institution of human bondage and I am now examining Washington’s perspective.

I do not consider myself ready to draw any concrete conclusions (yet) on Washington’s struggles over race. That said, I have found the obvious similarities and differences between Jefferson’s and Washington’s racisms to be most intriguing. Both Virginia planters benefited greatly from the institution in their own private enterprise while accumulating and maintaining their family’s wealth on the backs of their slaves. Washington however, ended his life with a mindset that differed from Jefferson’s. The slaves that Washington owned in his own right came from several sources. He was left eleven slaves by his father's will; a portion of his half-brother Lawrence Washington's slaves, about a dozen in all, were willed to him after the death of Lawrence's infant daughter and his widow; and Washington purchased from time to time slaves for himself, mostly before the Revolution.

David Hackett Fischer recently published a piece on Washington titled Born to Lead which contained an excellent sidebar describing this aspect of Washington’s life. Titled The Unapologetic Patrician, it presents a critical portrait of a social snob who begrudgingly maintained slaves until his death:

“Washington grew up among many inequalities, and he accepted most of them. He was very conscious of social rank. A sociable man among his peers, he was at his ease with others of his class and often in their company. From 1768 to 1775, he entertained 2,000 people at Mount Vernon, mostly “people of rank,” as he called them. He deliberately kept others at a distance and advised his manager at Mount Vernon always to deal that way with inferiors. “To treat them civilly is no more than what all men are entitled to,” Washington wrote, “but my advice to you is, to keep them at a proper distance; for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you sink in authority.” Washington had been taught to treat people of every rank with civility and “condescension,” a word that has changed its meaning in the modern era. In Washington’s world, to condescend was to treat inferiors with decency and respect while maintaining a system of inequality.

His world was also a hierarchy of wealth, and Washington acquired a large share of it. When his brother died, he became the master of Mount Vernon at the age of 22, leasing it from his sister-in-law, then owning it outright. At 36, he married Martha Parke Custis, a very beautiful and gracious woman and one of the richest widows in Virginia. By skillful management and good luck, his property increased rapidly before the Revolution. Public service diminished his wealth, and he was forced to sell large tracts of land to pay the expenses of his presidency, but even with that burden, he built one of the largest family fortunes in America, with a net worth of more than a million dollars. In 1799, his and his wife’s estates included many thousands of acres and 331 slaves.

Part of his world was hierarchy and race. In his early years, Washington owned many slaves and actively bought and sold them. Before the Revolution, he shared the attitudes of his time and place and fully accepted slavery, but after 1775, his thoughts changed rapidly. He began to speak of slavery as a great evil, and by 1777, he wrote of his determination to “get clear” of it. After much thought and careful preparation, he emancipated all of his slaves in his will.” (Bold emphasis added.)

It appears that Washington’s conscience was deeply troubled in his later years. His determination to free his slaves was likely a way of easing the burden of guilt. Unlike Jefferson, Washington freed all of his slaves upon his (and his wife’s) death, making no distinction between them. Every one was granted liberty regardless of their age, position, or stature within the household. Jefferson only freed certain slaves when he passed away and many more were sold off by his heirs to cover the immense debt that he had incurred while building Monticello. One could even say that Jefferson relinquished his slaves because he had to, while Washington appears to have done so because he wanted to. Here is an excerpt from Washington’s will that frees his slaves and commends them for their service (Note: the < > denotes where text was illegible, but can be assumed):

<Ite>m Upon the decease <of> my wife, it is my Will & desire th<at> all the Slaves which I hold in <my> own right, shall receive their free<dom>. To emancipate them during <her> life, would, tho' earnestly wish<ed by> me, be attended with such insu<pera>ble difficulties on account of thei<r interm>ixture by Marriages with the <dow>er Negroes, as to excite the most pa<in>ful sensations, if not disagreeabl<e c>onsequences from the latter, while <both> descriptions are in the occupancy <of> the same Proprietor; it not being <in> my power, under the tenure by which <th>e Dower Negroes are held, to man<umi>t them. And whereas among <thos>e who will recieve freedom ac<cor>ding to this devise, there may b<e so>me, who from old age or bodily infi<rm>ities, and others who on account of <the>ir infancy, that will be unable to <su>pport themselves; it is m<y Will and de>sire that all who <come under the first> & second descrip<tion shall be comfor>tably cloathed & <fed by my heirs while> they live; and that such of the latter description as have no parents living, or if living are unable, or unwilling to provide for them, shall be bound by the Court until they shall arrive at the ag<e> of twenty five years; and in cases where no record can be produced, whereby their ages can be ascertained, the judgment of the Court, upon its own view of the subject, shall be adequate and final. The Negros thus bound, are (by their Masters or Mistresses) to be taught to read & write; and to be brought up to some useful occupation, agreeably to the Laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, providing for the support of Orphan and other poor Children. and I do hereby expressly forbid the Sale, or transportation out of the said Commonwealth, of any Slave I may die possessed of, under any pretence whatsoever. And I do moreover most pointedly, and most solemnly enjoin it upon my Executors hereafter named, or the Survivors of them, to see that th<is cla>use respecting Slaves, and every part thereof be religiously fulfilled at the Epoch at which it is directed to take place; without evasion, neglect or delay, after the Crops which may then be on the ground are harvested, particularly as it respects the aged and infirm; seeing that a regular and permanent fund be established for their support so long as there are subjects requiring it; not trusting to the <u>ncertain provision to be made by individuals. And to my Mulatto man William (calling himself William Lee) I give immediate freedom; or if he should prefer it (on account of the accidents which ha<v>e befallen him, and which have rendered him incapable of walking or of any active employment) to remain in the situation he now is, it shall be optional in him to do so: In either case however, I allow him an annuity of thirty dollars during his natural life, whic<h> shall be independent of the victuals and cloaths he has been accustomed to receive, if he chuses the last alternative; but in full, with his freedom, if he prefers the first; & this I give him as a test<im>ony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War. <end>

A detailed listing of Washington’s slaves is also available online at The Papers of George Washington. More on this subject to come.

Jefferson and Jesus

I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he [Christ] wished anyone to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other. - Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, April 12, 1803

I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he [Christ] wished anyone to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other. - Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, April 12, 1803

Without a doubt, one of the most complex aspects of Thomas Jefferson’s life story is the subject of spirituality. From his authoring of the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom and Jefferson Bible, to the many letters that he sent to friends and associates touting the teachings of Jesus Christ, Jefferson’s religious beliefs remain a perplexing riddle to this very day.

As a practicing Christian and historian, I have spent a great deal of time examining this subject and my dream of penning that best-seller revolves around a book that presents Jefferson’s experiences here in Fredericksburg when he agreed to draft the official document that separated church and state. A recurring interest, Jefferson’s attitudes on faith were the focus of the inaugural essay that I wrote for The Jefferson Project, as well as the initial debate that I participated in at Jefferson Today.

Below is a portion of my rebuttal from Jefferson Today. You can also read my essay, titled Jefferson’s Religious Freedom, over at The Jefferson Project. Plans are to open this subject up for discussion in a future posting, while providing additional insights and sources from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

CHRISTIAN CONSCIENCE?

Jefferson rejected the “divinity” of Jesus, but he believed that Christ was a deeply interesting and profoundly important moral or ethical teacher. He also subscribed to the belief that it was in Christ’s moral and ethical teachings that a civilized society should be conducted. Cynical of the miracle accounts in the New Testament, Jefferson was convinced that the authentic words of Jesus had been contaminated. His theory was that the earliest Christians, eager to make their religion appealing to the pagans, had obscured the words of Jesus with the philosophy of the ancient Greeks and the teachings of Plato. These so-called “Platonists” had thoroughly muddled Jesus’ original message. Firmly believing that reason could be added in place of what he considered to be “supernatural” embellishments, Jefferson worked tirelessly to compose a shortened version of the Gospels titled “The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth.” The subtitle stated that the work was “extracted from the account of his life and the doctrines as given by Matthew, Mark, Luke & John.”

On April 21, 1803, Jefferson sent a letter to Dr. Benjamin Rush, who was a fellow ‘Founding Father’ and devout Christian, explaining his own interpretation of scripture.

Dear Sir,

In some of the delightful conversations with you in the evenings of 1798-99, and which served as an anodyne to the afflictions of the crisis through which our country was then laboring, the Christian religion was sometimes our topic; and I then promised you that one day or other I would give you my views of it. They are the result of a life of inquiry and reflection, and very different from that anti-Christian system imputed to me by those who know nothing of my opinions. To the corruptions of Christianity I am indeed opposed, but not to the genuine precepts of Jesus himself. I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he wished anyone to be: sincerely attached to his doctrines in preference to all others, ascribing to himself every human excellence, and believing he never claimed any other. At the short interval since these conversations, when I could justifiably abstract my mind from public affairs, the subject has been under my contemplation. But the more I considered it, the more it expanded beyond the measure of either my time or information. In the moment of my late departure from Monticello, I received from Dr. Priestley his little treatise of “Socrates and Jesus Compared.” This being a section of the general view I had taken of the field, it became a subject of reflection while on the road and unoccupied otherwise. The result was, to arrange in my mind a syllabus or outline of such an estimate of the comparative merits of Christianity as I wished to see executed by someone of more leisure and information for the task than myself. This I now send you as the only discharge of my promise I can probably ever execute. And in confiding it to you, I know it will not be exposed to the malignant perversions of those who make every word from me a text for new misrepresentations and calumnies. I am moreover averse to the communication of my religious tenets to the public, because it would countenance the presumption of those who have endeavored to draw them before that tribunal, and to seduce public opinion to erect itself into that inquisition over the rights of conscience which the laws have so justly proscribed. It behooves every man who values liberty of conscience for himself, to resist invasions of it in the case of others; or their case may, by change of circumstances, become his own. It behooves him, too, in his own case, to give no example of concession, betraying the common right of independent opinion, by answering questions of faith which the laws have left between God and himself. Accept my affectionate salutations.

- Th: Jefferson

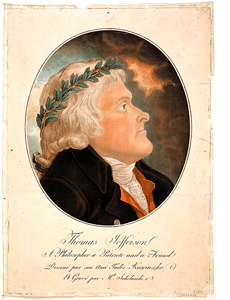

IMAGE: Thomas Jefferson, aquatint by Tadeusz Koo Ciuszko

NOT Black Confederates

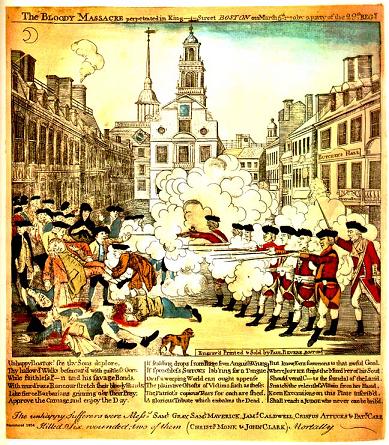

ABOVE: A cropping of The Death of Major Peirson by John Singleton Copley (Image © Tate, London 2008.) The artist painted a black soldier not present at the battle, wearing the uniform of a Royal Ethiopian. Copley knew of the Royal Ethiopian Regiment before his loyalty forced him to flee Boston. It is telling that he chose to include a Royal Ethiopian soldier in a battle at which the regiment never fought. As Black History Month comes to an end, I can't think of a better post to share today than the extraordinary story of the "Black Loyalists in New Brunswick." Without a doubt, one of the most highly controversial and contested subjects in today's historical studies (both in the public and academic arena) is the questionable history of Black "Confederates" during the American Civil War. In recent months this subject has been debated ad nauseum across the blogosphere and I touched on the subject in my recent book on Confederate encampments in Spotsylvania County.

The quarrel of course is why anyone would willingly take up arms on behalf of a cause that sought to keep them in bondage - vs. - the notion that many Africans fought beside their masters in order to protect their state's from Federal occupation. Those of you who read Campfires at the Crossroads may recall that I found the examples of black Confederates whom I cited to be slaves acting in the capacity of servants, not soldiers. The letters that I included testified to that conclusion.

Although that argument will continue for generations it seems, America's first revolution did, IN FACT, find blacks fighting alongside their white counterparts.

At the time of the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), it is estimated that there were over a half million African-Americans living in the thirteen colonies. As the rebellion's patriotic call to fight for liberty grew, the British government sought to undermine the expanding Continental Army by soliciting slaves who ran away from their masters. By promising to grant them their freedom and security, the Redcoat ranks were able to boost their manpower on the battlefield instead of constantly relying on the importation of additional troops who took months to travel to the Americas from England. Some of these all-black units even flourished as in the example of the Royal Ethiopian Regiment and later, the Black Pioneers.

According to the Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives website Black Loyalists in New Brunswick: "In November 1775, Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore, hoping to bolster the British war effort, encouraged slaves and indentured servants of the Patriots to join His Majesty's army. Many did so. When the British evacuated their army from Boston to Halifax in 1776, a "Company of Negroes" was part of the entourage. British Commander-in-Chief Sir Henry Clinton extended the policy of appealing to African Americans in his Phillipsburg Proclamation of 1779 in which he offered security behind British lines to 'every negro who shall desert the Rebel Standard.'"

Following the British Army's surrender, it is estimated that nearly 35,000 loyalists fled the United States to settle north in the provinces of Canada including the maritime regions of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Nearly 3,500 free black loyalists were among them including many who had fought alongside the Redcoats on behalf of the English crown. New Brunswick saw thousands of African-Americans settle in as new citizens and many went on to fight again for Britain in the War of 1812. Despite their service to the king, many black loyalists and their families still faced racial discrimination, although it paled in comparison to the institution of slavery that continued to thrive in the southern United States.

For a complete history, visit Black Loyalists in New Brunswick 1783-1854. This outstanding project is a digital collection hosted by the Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives and features document and petition transcripts, rare images, as well as lesson plans and resources for teachers.

I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he [Christ] wished anyone to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other. -

I am a Christian, in the only sense in which he [Christ] wished anyone to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other. -