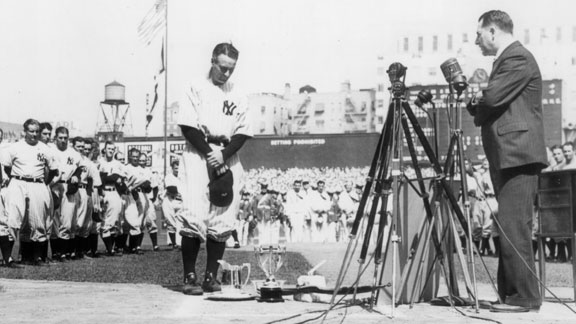

ABOVE: Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium, July 4, 1939.

Today’s post is a little 'off-topic' as it presents another one of my favorite genres of historical study, baseball. My first 'paid-gig' as a writer was that of a contributing historian for Baseball-Almanac.com (2000-2006). Next spring, Eric Wittenberg and I will debut our new book titled You Stink! Major League Baseball’s Terrible Teams and Pathetic Players (The Kent State University Press). The anticipation that is already buzzing around this title is very much appreciated and I for one cannot wait to promote it. This past weekend I shared a rather lengthy, and in-depth conversation with a Red Sox aficionado who was willing to acknowledge that there was at the very least, one Yankee he admired. This one's for him...

Lou Gehrig’s performance on the field made him an American icon, but it was his tragic and untimely death that made him unforgettable. A real-life folk hero, Gehrig was everything a professional baseball player should and shouldn’t be. A quiet man who “carried a big stick,” Gehrig was a blue-collar champion. His records and statistics spoke louder than his actions and his career numbers still rank among the highest in the history of Major League Baseball. As a member of baseball’s most storied franchise, his accomplishments with the first Yankees dynasty are without question. His dedication to the game was certainly second to none, yet beyond baseball, there was nothing newsworthy or spectacular about him. In the words of his widow, Eleanor, “He was just a square, honest guy.”

Simply stated, Lou Gehrig was a baseball player…a great baseball player. All-Century Teammate, Hall of Famer, Triple Crown Winner, All-Star, World Series Champion, Most Valuable Player… these are just some of the terms used to describe the one they called “The Iron Horse.” Unlike the players of today, Gehrig spent his entire professional career with the same team while wearing the blue pinstripes in his hometown of New York City. His life story represented the “American Dream” and read more like a Hollywood movie script. Surprisingly more fact than fiction, it was appropriately translated into THE PRIDE OF THE YANKEES, which was nominated for eleven Academy Awards in 1943 and is still regarded by many today as the finest baseball movie ever made. His statistics spoke volumes as well and continue to prove that his impact on our national pastime remains second to none by a player from his era.

For starters, his lifetime batting average was .340, fifteenth all-time highest, and he amassed more than 400 total bases in five seasons. A player with few peers, Gehrig remains one of only seven players with more than 100 extra-base hits in one season. During his career he averaged 147 RBIs a year and his 184 RBIs in 1931 still remains the highest single-season total in American League history. Always at the top of his game, Gehrig won the Triple Crown in 1934, with a .363 average, 49 homers, and 165 RBIs, and was chosen Most Valuable Player in both 1927 and 1936. Unbelievable for a man of his size, #4 stole home 15 times, and he batted .361 in 34 World Series games with 10 homers, eight doubles, and 35 RBIs. Still standing is his record for career grand slams with 23. Gehrig hit 73 three-run homers, as well as 166 two-run shots, giving him the highest average of RBIs (per homer) of any player with more than 300 home runs. Not bad for a guy who originally entered Columbia University with the intention of becoming an engineer!

For most ballplayers, this would have been more than enough fare for a ticket to Cooperstown, but for Gehrig, the aforementioned stats are only a glimpse into his brilliant career. Still the only player in history to drive in 500 runs in three years, he also hit 493 home runs (while playing first), the most by any first baseman in history. On June 3, 1932, Gehrig became the first American Leaguer to hit four home runs in a game and he was the first athlete to have his number officially retired in 1939. A true thoroughbred, he was christened the “Iron Horse” when he held the “unbreakable” record of 2,130 consecutive games played, until 1998, when it was finally topped by another “Iron Man” named Cal Ripken Jr. A tireless worker, Gehrig played every game for more than 13 years despite a broken thumb, a broken toe and back spasms. Later in his career, his hands were X-rayed and doctors were able to spot 17 different fractures that had “healed” while he continued to play. This toughness could be attributed to the fact that he was the only surviving child (out of 4) of hard-working German immigrants. Somehow though, even his resilient exterior could not overcome the growing sickness he hid within.

Things began to change in 1938 as Gehrig struggled and fell below .300 for the first time since 1925. He appeared clumsy and sluggish on (and off) the field and it was painfully clear that there was something wrong. He lacked his usual dominant swing and many pitches that he would have normally hit out of the ballpark fizzled into meager fly outs. Initially, doctors diagnosed him with having a gall bladder problem and put him on a bland diet, which only made him weaker. Determined to work through his pain, he managed to play in the first eight games of the 1939 season, but fatigue weighed on his bat and he was barely able to field the ball. Gehrig knew that when his fellow Yankees had to congratulate him for stumbling into an average catch, it was time for him to leave. Eventually, he took himself out of the game and unfortunately, he would never return.

After a battery of tests, doctors at the Mayo Clinic diagnosed Gehrig as having a very rare form of degenerative disease called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The prognosis was terminal and there was no chance that he would ever play baseball again. Aware that his days were numbered, he continued to carry himself with unwavering dignity, despite being unable to conceal his failing health.

Local sports writer Paul Gallico suggested that the team should have a recognition day to honor Gehrig on July 4, 1939. In attendance were Mom and Pop Gehrig, Eleanor Gehrig (wife), and all the 1939 Yankees with manager Joe McCarthy. Other guests included Bob Meusel, Bob Shawkey, Herb Pennock, Waite Hoyt, Joe Dugan, Mark Koenig, Benny Bengough, Tony Lazzeri, Arthur Fletcher, Earle Combs, Wally Schang, Wally Pipp, Everett Scott, New York Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia, US Postmaster General James A. Farley, and the New York baseball writers dean and MC for the ceremony, Sid Mercer. Babe Ruth showed up late, as was his typical fashion, and drew a loud cheer from the crowd. Gehrig was touched that there were so many people there on his behalf, but he had mixed emotions about Ruth being there. The two, once good friends, had not spoken in years.

Gehrig historian Sara Kaden Brunsvold, recalled the ceremony:

During the first game, Gehrig stayed in the Yankee dugout anxiously awaiting the ceremony that would take place at home plate at the end of the game. Similarly Joe McCarthy was fretting over the words he would say to Gehrig during the ceremony. Neither man thought himself articulate, and neither looked forward to having so many eyes on them. Whereas Gehrig decided to do the best he could with the impending ceremony, McCarthy was so nervous he became irritable. But he still had presence of mind enough to notice how frail Gehrig looked, and he pulled some of the Yankees players aside and told them to watch Gehrig during the ceremony in case he should start to collapse.

Finally the first game was over and workers set up a hive of microphones behind home plate. The Yankee players of the current year and yesteryear lined up along the foul lines. Gehrig was placed near the microphones. A line of well-wishers from various occupations and fame came to the mics to say sweet, sweet things to Gehrig and about Gehrig. Some tears escaped from his eyes while he nervously, humbly hung his head and made a small circle of impressions in the dirt with his spikes. He took every word said to heart.

McCarthy came to the mics to say his piece with limbs trembling just as much as Gerhig’s. Despite his uneasiness, McCarthy was as heartfelt as he could manage, fighting the urge to bawl like a baby out of respect to Gehrig’s shaky emotions. Because McCarthy and Gehrig were very close, almost a father-son relationship, McCarthy knew that if he started crying it would probably make things that much worse for Gehrig trying to get through the ceremony. The most memorable part of his speech was when he assured Gehrig that no matter what Gehrig thought of himself, he was never a hindrance to the team.

Gehrig was given a number of presents, commemorative plaques, and trophies. Some came from the big-wig people; and, touching, some came from folks of the Stadium’s janitorial service and groundskeepers. The most talked about present Gehrig received was a silver trophy with all the Yankee players’ signatures on it presented by McCarthy. Inscribed on the front was a poem the Yankees had asked Times writer John Kieran to pen:

We’ve been to the wars together,

We took our foes as they came;

And always you were the leader,

And ever you played the game.

Idol of cheering millions;

Records are yours by sheaves;

Iron of frame they hailed you,

Decked you with laurel leaves.

But higher than that we hold you,

We who have known you best;

Knowing the way you came through

Every human test.

Let this be a silent token

Of lasting friendship’s gleam

And all that we’ve left unspoken.

- Your Pals on the Yankee Team

With more than 62,000 fans in attendance, Gehrig slowly stepped up to a bank of microphones and spoke those immortal words of thanks in one of the most heartfelt speeches ever given. As a testament to his courage and selflessness, he opened his remarks with the famous line, “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.”

He continued: “I have been in ballparks for seventeen years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans. Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert - also the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow - to have spent the next nine years with that wonderful little fellow Miller Huggins - then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology - the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy! Sure, I’m lucky. When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift, that’s something! When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies, that’s something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles against her own daughter, that’s something. When you have a father and mother who work all their lives so that you can have an education and build your body, it’s a blessing! When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed, that’s the finest I know. So I close in saying that I might have had a tough break - but I have an awful lot to live for!”

His obituary, as printed in the New York Times, outlined his contributions to the community both on the baseball field and off:

...Regarded by some observers as the greatest player ever to grace the diamond, Gehrig, after playing in 2,130 consecutive championship contests, was forced to end his career in 1939 when an ailment that had been hindering his efforts was diagnosed as a form of paralysis. ...But as brilliant as was his career, Lou will be remembered for more than his endurance record. He was a superb batter in his heyday and a prodigious clouter of home runs. The record book is liberally strewn with his feats at the plate.

As a fitting tribute, Lou Gehrig was elected to the Hall of Fame that December. During the last months of his life, he worked on youth projects for New York until he was unable to walk. He died in 1941, at the age of 37. He was cremated, and his remains are in Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, roughly, 45 minutes from Manhattan. A headstone for Gehrig was erected that mistakenly claims he was born in 1905 (he was really born in 1903). His sudden death brought national attention to this relatively unknown affliction known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the illness has since been renamed “Lou Gehrig’s Disease”. His position in the public eye helped to inspire more intensive research and today the ALS medical community is hopefully getting closer to finding a cure.

The tragedy of his death still resonates today with baseball historians, players and fans all around the world. And it is important that we all remember that his contributions as a man far exceed those of a mere ballplayer. Lou Gerhig proved that anyone could achieve his or her dreams through hard work and determination. He then exhibited an iron-man work ethic that has only been broken once in the history of the game. Finally, he showed how courage and class could carry one through the most difficult of times.

Lou Gehrig accomplished more in his short life than most athletes could ever dream. He was a pure ballplayer at a time when the game was pure. As the years go by, so does the distance between young fans and the players of Gehrig’s era. Their game was timeless and we may never experience baseball as it was experienced back then.

EXTRA: Lou Gehrig's Lifetime Statistics at Baseball-Almanac.

Updated: Monday, 13 June 2011 1:35 PM EDT

Permalink | Share This Post