Following the Protestant Reformation of the 1500’s, a strong movement arose against the Catholic Church of England. Many immigrants brought their own anti-Catholicism beliefs with them to the New World where it eventually became a mainstream point of view. Their prejudices were based on political and theological differences. In 1642, the Colony of Virginia went so far as to enact a law prohibiting Catholics from settling there. A similar proclamation was drafted by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The results were a drastic difference between protestant and Catholic settlers. Even "Catholic-friendly" states had remained unbalanced. In 1634, the state of Maryland recorded less than 3,000 Catholics out of a population of 34,000 (around 9% of the population).

Many of the Founding Fathers who preached of liberty and religious freedom distrusted the denomination. Samuel Adams echoed this sentiment stating, “What we have above everything else to fear is Popery.” Thomas Jefferson condemned the Roman Catholic clerics when he wrote, “History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government,” and, “In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own.” John Adams attended a Catholic mass in Philadelphia in 1774 and later ridiculed the rituals practiced by parishioners.

Looking back to those days of intolerance it may be surprising to find that it was General George Washington, a consummate politician, who rose above public opinion to support his Catholic countrymen. Washington was one of the first leaders to be outspoken on the subject of religious bigotry and he took a great risk by voicing an unpopular sentiment. In retrospect this move may have been far more practical than benevolent as Washington no doubt realized that he needed to win the favor of foreign countries that accepted Catholicism, especially France. He also required the service of Catholic military men both domestic and foreign. This included the Marquis de Lafayette, a Catholic Frenchmen who would play a major role in America’s fight for independence.

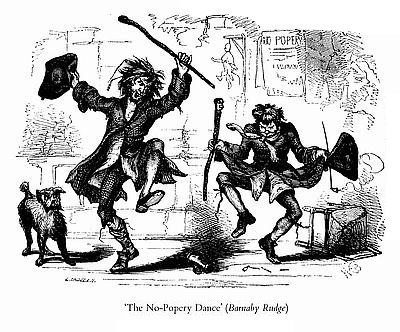

For years the country’s Englishmen had celebrated “Guy Fawkes Day” also known as “Pope’s Day” on November 5th. The importance of this date commemorated an incident known as “The Gunpowder Plot” in which a Catholic dissident named Guy Fawkes attempted to blow up Parliament in 1605. As part of the festivities, an effigy was burned, depicting the sitting Pope of the Catholic Church. In November of 1775 Washington issued general orders condemning what he called a “ridiculous and childish custom of burning the effigy of the pope.” He added that “American Catholics are among those we ought to consider as brethren embarked on the same cause, the defense of the general liberty of America.” By taking this stand against religious bigotry, Washington appeared both tolerant and diplomatic. This likely helped him to secure the French allies which he desperately needed to win the war. His entire proclamation read:

As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form'd for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope--He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are solliciting, and have really obtain'd, the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defence of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.

Although anti-Catholic sentiment remained in America for some time to come, the official banning of “Pope’s Day” by one of America’s most revered leaders dampened the spirit tremendously. By 1776 the tradition was no longer acknowledged by the masses. This change in public opinion allowed the once ostracized denomination to flourish beside its protestant brethren. Today the Catholic faith makes up almost 24% of the U.S. population with 301 million members.

The nation’s current Muslim citizenship is estimated at approximately 2.6 million, much of which is ostracized like the Catholics of days past. Just as the bloody history of the Crusades blemished the Catholics reputation during colonial times, today’s anti-Muslim sentiments resulted from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Ironically the resulting military actions in the Middle East sent scores of Muslims fleeing the extreme-fundamentalism of their own faith to seek sanctuary in the United States. This mass influx of refugees mirrored that of the earliest Christians who fled from Europe to the New World in order to escape religious persecution. Today the debate remains over the acceptance of Muslim customs and religious practices. This includes the issue of requiring assimilation for nationalization.

Just as early immigrant Catholics were judged on the sins of the crusaders, Muslims in today’s time are often feared to be jihadists. This underlying suspicion has led to a heightened form of prejudice that is often masked behind the guise of vigilance. Perhaps this is no more illustrated than in the recent proposal to add an anti-Shariah amendment into Texas’s constitution. Proponents of the law believe that it is crucial to maintaining the fundamentals of the country, while those who oppose it believe an official denunciation of the Muslim faith by the government to be contrary to the country’s founding principles of “liberty and justice for all.” When examining this argument strictly from a constitutional point of view, it’s not that hard to see both perspectives. Hence the conundrum. Mainstream American-Muslims would certainly never practice such primitive traditions, but the radical-extremists who have hijacked their faith continue to pose a real threat.

This controversial amendment would not be the first time that a clause was instituted to negate a particular religious group. Prior to Washington’s advocacy several states had devised loyalty oaths designed to exclude Catholics from holding state and local office. Yet at the same time Catholics were serving at the Constitutional Convention. This included Thomas Fitzsimons and Daniel Carroll who were delegates from Pennsylvania and Maryland. Both men’s signatures appear on the U.S. Constitution. Carroll had served in the Continental Congress and had signed the Articles of Confederation as well.

Another close comparison between Catholics of the past and Muslims of the present exists in military manpower. Just as Washington’s ranks of the Continental army included Catholic troops, today’s military boasts between 10,000-20,000 Muslims (according to the Department of Defense). The military’s rising requirement for Muslim chaplains is also a testament to the expanding integration of followers of Islam. Ironically, most of the conflicts that the U.S. military is currently engaged in revolve around religious differences between cultures. Muslims are fighting against Muslims on behalf of the U.S. – just as Catholics fought against members of the Catholic Church of England on behalf of their fellow colonists.

To this day religion still remains the great divider. Regardless of one’s spiritual preference, it does us well to recall the sins of our past in order to deal more justly with the present. Only time will tell if the post-traumatic reaction from 9/11 can be healed in the name of unity. Until then we can all gain a unique perspective of what it feels like to be a Muslim by remembering what it once felt like to be a Catholic.

Updated: Tuesday, 22 March 2011 6:07 PM EDT

Permalink | Share This Post