Race and Remembrance at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

HISTORY AND HYPOCRISY

Thomas Jefferson is remembered as perhaps the most exceptional charter member of the Founding Fathers. His contributions to the birth of our nation are second-to-none and his words have inspired generations of Americans to covet their freedom and liberty. At the same time, the author of the Declaration of Independence is criticized as the most hypocritical affiliate of that revolutionary generation. The largest point of contention in this Virginia planter's legacy is his lifelong practice of slavery and how it benefited him socially, politically, and personally. It is an emerging blemish on an otherwise brilliant existence.

Jefferson experienced the so-called "peculiar institution" of bondage directly, as Monticello's slave population was one of the largest in Virginia. His community of human property resided just over the hill from the main house, on what was referred to as "Mulberry Row." Often Master Jefferson would walk along the path tracing the 150-plus slave workforce community which included family dwellings, wood and ironwork shops, a smokehouse, a dairy, and a wash house and stable. "Mulberry Row" was the center of plantation activity from the 1770s to Jefferson's death in 1826. Five log cabin dwellings were also built near the site for additional household servants who did not fit in the basement-level dependency wings of the estate. Today, visitors can trace Jefferson's footsteps on the grounds of Monticello. Although many of the outbuildings are no longer standing on the property, several slave cabins have been recreated. The dependency wings are open to the public and the adjoining kitchen and sleeping quarters appear much the same as they did in Jefferson's time. Despite the initial appearance of a bustling plantation community, one cannot forget that it was populated by slaves. And regardless of the quality of life that Jefferson's servants appear to have shared over other Africans held in bondage, they were still held as property.

Like their proprietor, Monticello slaves maintained an arduous schedule. Most servants worked from dawn to dusk, six days of the week. Only on Sundays and holidays could they pursue their own affairs. These included prayer meetings and worship, spiritual singing, and night excursions, when wild honey would be gathered for their personal consumption. The supplementing of rations was also practiced as farm hands grew acres of vegetables, fished the river, and trapped game. Unlike many masters, Jefferson actually paid his slaves a monetary share for extra vegetables, chickens, and fish for the main house, as well as for special tasks performed outside their normal working hours. He also encouraged some of his enslaved artisans by offering them a percentage of what they produced in their shops. An extremely diversified man himself, Jefferson was most likely impressed by the skills that were cultivated by his slaves. In this respect, his treatment of them imitates a mutual respect for hard working individuals who cared about contributing to Monticello's well-being. Jefferson's very good friend James Madison also appreciated the vocations exhibited on Mulberry Row and purchased all of the nails used to enlarge his neighboring estate of Montpelier from Jefferson's nail foundry.

The conflict that existed between Jefferson, the slaveholder and Jefferson, the proponent of liberty is still being debated and examined to this very day. According to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, who is tasked with preserving and presenting the storied legacy of its namesake, Jefferson's words and deeds are contradictory on the issue of slavery. Although he drafted the words "all men are created equal," and worked to limit the stranglehold of slavery on the new country, he personally found no political or economic remedies for the problem, and trusted that future generations would find a solution. "But as it is," Jefferson wrote, "we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other."

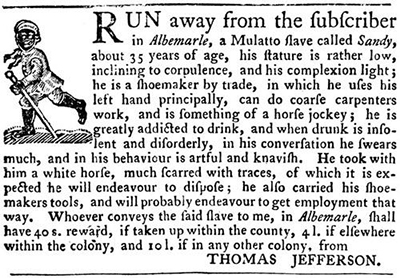

For his entire life, Thomas Jefferson was surrounded by the practice of slavery. In 1764, he inherited 20 slaves from his father. Ten years later, he inherited 135 more from his father-in-law, John Wayles, who was involved in the importation of enslaved Africans into Virginia. By 1796, Jefferson owned approximately 170 slaves with 50 living on his property in Bedford County and 120 residing in Albemarle. Each residence was completely dependent on the use of forced labor, from the planting of fields to the daily operations of the house. Slave labor was also the economic force behind many of Jefferson's enterprises. It seems that his lifestyle demanded the practice, regardless of his prejudices against it.

Ironically, throughout his career, both politically and personally, Jefferson repeatedly voiced displeasure with the institution of slavery. He often referred to it as an "abominable crime," a "moral depravity," a "hideous blot," and a "fatal stain that deformed what nature had bestowed on us of her fairest gifts." He was successful in outlawing international slave trade in the Old Dominion, but continued to keep slaves on all of his farms in Virginia. This blatant contradiction illustrates the complexity that was Thomas Jefferson. One conclusion is that he believed that a practicable solution to this moral dilemma could not be found in his lifetime. He still continued, however, to advocate privately his own emancipation plan, which included a provision for colonizing slaves outside the boundaries of the United States.

Without a doubt, the most controversial issue, with regard to slavery and the legacy of Thomas Jefferson, is his relationship with Sally Hemings. Several books have been published that specifically deal with the subject, including the Pulitzer Prize winning book entitled "The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family" by Annette Gordon-Reed and the counter-argument entitled "In Defense of Thomas Jefferson: The Sally Hemings Sex Scandal" by William G. Hyland Jr. A house slave, Sally was the half-sister of Jefferson's deceased wife, Martha. Not merely a modern scandal, rumors that Jefferson had fathered multiple children with Sally Hemings entered the public arena during his first term as president. It continued to hang over Jefferson's memory for many years. In 1998, Dr. Eugene Foster and a team of geneticists revealed that they had "established that an individual carrying the male Jefferson Y chromosome fathered Eston Hemings (born 1808), the last-known child born to Sally Hemings. There were approximately 25 adult male Jeffersons who carried this chromosome living in Virginia at that time, and a few of them are known to have visited Monticello." The study's authors, however, said, "the simplest and most probable conclusion was that Thomas Jefferson had fathered Eston Hemings."

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation's official statement on the matter declares, "Although the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings has been for many years, and will surely continue to be, a subject of intense interest to historians and the public, the evidence is not definitive, and the complete story may never be known. The Foundation encourages its visitors and patrons, based on what evidence does exist, to make up their own minds as to the true nature of the relationship." This adds an entirely new layer to the complexity of Thomas Jefferson's views, not only on slavery, but also on race in general.

To this day, the "Hemings Affair" remains a hotly contested topic among Jefferson experts and enthusiasts alike. It is inevitably a mark on the life of a man who ultimately helped to establish a nation built on the foundation of freedom. Ironically, the division over the matter is often rooted in conflicting racial perspectives. This has been expressed in a variety of ways over the years. Regardless of the color of their skin, some individuals do not feel comfortable with the idea of an interracial or intimate relationship between a master and his slave. Others are bothered by either the notion of an older white man taking advantage of a younger black woman, or the hypocritical practice of owning some African-Americans while simultaneously bedding another. Perhaps there is no clear conclusion to the mystery surrounding this relationship. Still it speaks to the idea that different people of different races look upon the matter in different ways.

Beyond the bounds of his estate, Jefferson, like many powerful Southerners, benefited greatly in the political spectrum through the ownership of African-Americans. Many experts have argued that Jefferson's election, as the third President of the United States, came solely due to the South's augmented representation in the Electoral College, which included a 60% census of slaves who were counted as 3/5 of a vote. At the time, detractors of his election referred to Jefferson as "the negro president" and criticized the clause in the Constitution that they believed enabled him to achieve victory. This factor was part of a compromise put in place to maintain a balance of voting power between the northern and southern states. As metropolitan communities in the north were more densely populated, Southern representatives demanded to have a portion of their slaves counted in the overall census. This would enable them to close the so-called "voter's gap" at the ballot box by increasing their numerical representation. The result was a more aggressive importation of Africans that ultimately secured more power for the slave states.

In his book entitled "Negro President" Jefferson and the Slave Power historian Gary Wills explains the monumental affects of the slave-clause: "In the sixty-two years between Washington's election and the Compromise of 1850, for example, slaveholders controlled the presidency for fifty-years, the speaker's chair for forty-one years, and the chairmanship of House Ways and Means Committee [the most important committee] for forty-two years. The only men to be re-elected president - Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Jackson - were all slaveholders. The men who sat in the speaker's chair the longest - Henry Clay, Andrew Stevenson, and Nathaniel Macon - were slaveholders. Eighteen out of thirty-one Supreme Court justices were slaveholders."

MEMORIES AT MONTICELLO

Today, the largest monument to the memory of Thomas Jefferson can be found at his beloved plantation. There stands one of the most celebrated and recognizable houses in all of America. It is the only private residence to be featured on U.S. currency and is heralded as a masterpiece of both form and function. Each year, millions of visitors traverse the rolling hills of Virginia to walk in the footsteps of a man who accomplished more in his lifetime than most. Upon arriving at Jefferson's estate, many feel a sense of awe at the magnificent architecture, beautiful gardens and the breath-taking view of the valley that surrounds Monticello Mountain. Inside the main house, they remain in astonishment of Jefferson's boundless creativity, ingenuity and practicality. Every room and every item appears to have a distinct purpose. Beneath the dependency wings, visitors can also appreciate the daily contributions of the house staff, from the baking of bread in the kitchen to the ingenious preservation of perishable goods in the icehouse. A visit to the nearby museum reinforces the notion that few men were as intelligent or as creative as Jefferson and that few households in the Commonwealth were as productive as Monticello.

One of the most welcome and recognizable additions to the site can be found in the vastly improved interpretation of slavery and the inclusion of more African-American perspectives. As the subject of slavery is certainly an uncomfortable one, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation should be applauded for its renewed commitment to expanding the stories of those who experienced slavery firsthand. Five major parts of the Monticello experience now recall the institution. These include the newly expanded visitor's center and gallery, the house tour, Mulberry Row, the visitor's guidebook and the slave cemetery.

VISITOR'S CENTER

This year marked the grand opening of the Thomas Jefferson Visitors Center and Smith Education Center at Monticello. There are two main galleries at this location (along with a theater, café, gift shop, and research library). Both exhibit halls feature specific displays dealing with slavery and the labor force at Monticello. Both sections appear dedicated to recognizing the contributions of the African-American community. In the upstairs gallery there is a biography card on Issac Jefferson who had served as a blacksmith, tinsmith, and nailer. Issac's memoirs were recorded by an interviewer and remain among the most insightful narratives about the day-to-day lives of Monticello's inhabitants. Isaac held a sincere affection for his owner and was reported as saying, "Old Master was very kind to servants."

Next to Issac's display are matching bios of John Hemings, a tremendously skilled woodworker who crafted much of the interior woodwork of Jefferson's house at Poplar Forest, as well the most famous of all Monticello's slaves, Sally Hemings. In addition to these bio cards, artifacts that include some of the black artisans' handiwork are on display. The craftsmanship that these men demonstrated is even more impressive when considering the lack of technology that exists today. In many instances, slave labor equaled skilled labor.

In the downstairs gallery, a large display titled "Those Who Built Monticello" presents the tradesmen, free and enslaved, as well as the tools they used to construct Jefferson's magnificent estate. According to the plaque, "Jefferson required highly-skilled workmen to realize his vision for Monticello. In Philadelphia in 1798 he engaged James Dinsmore, an Irish house joiner, to take charge of the ongoing construction in his absences. Dinsmore worked closely with enslaved joiner John Hemings to create much of Monticello's fine woodwork. The team of joiners also included James Oldham (1801-04) and John Neilson (1805-09), and another enslaved man, Lewis..."

It continues, "John Hemings, the son of Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings, apprenticed under Dinsmore and hired joiners. He became an accomplished craftsman, succeeded Dinsmore as head joiner in 1809, and trained other slaves in his trade, including his nephews Madison and Eston Hemings. A Monticello overseer recalled that Hemings ‘could make anything that was wanted in woodwork.' He made fine furniture, a landau carriage, and much of the interior woodwork at Poplar Forest. Jefferson freed Hemings in his will and gave him all the tools of his shop. Continuing to work for the Jefferson family, Hemings lived for several more years at Monticello with his wife, Priscilla."

MAIN HOUSE AND DEPENDENCIES

Nothing major has visibly changed noticeably at the top of the hill, although the guided tours are now more open to discussing the institution of slavery and how it was a crucial element in the construction, maintenance and operation of Monticello. Some guides are known to immediately make a point of presenting Jefferson as a typical Virginia plantation owner who had established his lifestyle on the benefits of slave labor. Others quote Jefferson as saying that he abhorred slavery and believed that he looked at his slaves with a paternalistic view; that they were children who required his supervision; then counter that notion by saying that dozens of Monticello's slaves had been gifted and/or sold off by Jefferson; and that if one judged him by his deeds and not his words, slavery was something that benefited him greatly.

Underneath the house, there remain several displays in the center alcove presenting the servants' quarters, artifacts, and slave lifestyle, including that of Issac Jefferson. The kitchen areas in particular present how Jefferson had his slave cooks trained by French chefs in the traditional dish preparations of the time. Adjacent quarters present the life of a slave named Joseph Fossett. The plaque reads, "Joseph Fossett (1780-1858) was the grandson of Elizabeth (Betty Hemings) and the son of Mary Hemings Bell, who became free in the 1790s while her son remained a slave at Monticello. According to overseer Edmund Backon, Fossett, a blacksmith, was ‘a very fine workman; could do anything it was necessary to do with steel or iron.' Joseph and Edith Fossett had ten children, from James, born in the President's House in 1805, to Jesse, born in 1830. Although Joseph Fossett was freed in Jefferson's will, his wife and children were sold at the Monticello estate auction in 1827. He continued to work as a blacksmith and, with the help of his mother and other free family members, was able to purchase the freedom of Edith and some of their children. They moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in the 1840s. In 1850 their son Peter, who left a number of recollections of his life, became free and joined his family in Cincinnati, where he was a prominent caterer and Baptist minister."

MULBERRY ROW

Perhaps the most direct display of slave life at Monticello is the stops along Mulberry Row. In addition to traditional placards, brick ruins mark the areas of significance. Named for the mulberry trees planted along it, Mulberry Row was the center of plantation activity at Monticello from the 1770s to Jefferson's death in 1826. Five log dwellings for slaves were located on Mulberry Row in 1796. The Mulberry Row cabins were occupied mainly by household servants who did the cooking, washing, house cleaning, sewing, and child tending. According to Monticello's website, "Not all slaves lived on Mulberry Row. A small number who were household servants lived in rooms in the basement-level dependency wings of Monticello, and others lived in cabins located elsewhere at Monticello and outlying farms." It is estimated that in 1796 there were over 110 African-Americans living on the 5,000-acre plantation, with almost half of them being children.

Stops along the way include slave dwellings, a workman's house, a storehouse, a blacksmith shop, a nailery and a joinery. Some people may not be aware that all building materials including Monticello's bricks and nails were made on-site and they will most certainly be surprised to learn that white workers lived along this section of the estate. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation states that, "A blacksmith shop was built on this site about 1793. Here Jefferson's slaves Little George, Moses, and Joe Fossett shoed horses, repaired the metal parts of plows and hoes, replaced gun parts, and made the iron portions of the carriages that Jefferson designed. Neighboring farmers brought work to the shop as well, and the slave blacksmiths were given a percentage of the profits of their labor. In 1794, Jefferson added a nail-making operation to the shop, in an effort to provide an additional source of income. Nail rod was shipped to Monticello by water from Philadelphia and was hammered into nails by as many as fourteen young male slaves, aged ten to sixteen." The crumbled foundation of a typical Mulberry Row slave cabin remains. According to the plaque, the structures were approximately 20 ft. x 12 ft., constructed of logs on a stone foundation, with a wood chimney and earth floor. These buildings overlooked the main produce gardens. Today there is a special Plantation Tour available that covers the slave community and its daily contribution in more detail. Mulberry Row is a main focal point of the walking tour.

VISITOR'S GUIDEBOOK

As with most of the nation's historical sites, Monticello also provides a quality guidebook along with each ticket purchase. This includes both an adult and a child's version. In the past, some patrons have criticized the child's pamphlet as it contains "cheerful" illustrations that explain the day-to-day life at Monticello by depicting slaves happily cooking in the kitchen and playing with the Jefferson children around the fish pond. No doubt slave-master relationships like this existed, but these representations can be viewed as illustrating complacency. Both sides of this argument are understandable as little children are perhaps too young to understand or comprehend the issues of slavery, yet these candy-coated drawings gloss over the issue altogether.

The adult guidebook that is currently distributed features two large spreads dealing with slave labor. The first is titled "Mulberry Row" and includes an illustrated map of the grounds and photographs of artifacts. Once again Issac Jefferson makes an appearance (clearly the most exhibited slave on the premises). A section on the storehouse states, "In 1796 Jefferson recorded that the log building here was used for storing iron and nail rod for the blacksmith shop and nailery. It also served over time for tinsmithing and nail manufacture and as a dwelling. A slave named Issac Jefferson, trained as a tinsmith in Philadelphia, briefly operated the tin shop."

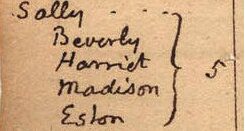

The second spread is titled "The Plantation" and deals specifically with the institution of slavery. It states, "Most of Jefferson's slaves came to him by inheritance - 20 from his father and 135 from his father-in-law. In 1782, he was the largest slaveholder in Albemarle County. For most of his life he was the owner of 200 slaves, two-thirds of them at Monticello and one-third at Poplar Forest, his plantation in Bedford County." A photograph of Jefferson's record of slaves complements the copy and a sidebar deals directly with the subjects of enslaved families.

It states, "Enslaved Families: A number of extended families lived in bondage at Monticello for three or more generations, facilitating Jefferson's operations as farm laborers, artisans, tradesmen and domestic workers. Among them were the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of Elizabeth Hemings, David and Isabel Hern, Edward and Jane Gillette, and James and Cate Hubbard. Nights, Sundays, and holidays provided the only opportunities to socialize and nurture their connections that united them as a community. Like their fellows across the South, Monticello slaves resisted slavery's dehumanizing effects by filling this time with expressions of a rich culture: gardening, needlework, music, religious practice. They were part of a cultural and spiritual life that flourished independent of their masters."

SLAVE CEMETERY

One additional area that befits the attention of this study is the small African-American graveyard that is located on the grounds of the estate. According to the sign, this cemetery is the final resting place of 40+ blacks who lived in slavery at Monticello from 1770-1827. It adds that although the names of Jefferson's slaves were known, it has not been possible to identify any of those buried here. This is perhaps one of the most telling of all the exhibits, as a separate burial plot personified the society of segregation that, even in death, existed at Thomas Jefferson's home.

Thanks to these new expansive interpretations, visitors to the new Monticello are more likely to come away with a more complex perspective of the man, as well as new conclusions. Many will acknowledge that the Thomas Jefferson we recognize today was a man who may very well have held a sincere paternalistic fondness for his slaves, but at the same time, he held them in the chains of bondage. And despite the fact that many of his servants received specialized training and developed trades that resulted in the creation of great things, they were simultaneously denied the basic principle of freedom. This is where the contradiction of the patriot who penned the most famous call for liberty lies. Thomas Jefferson was an extraordinary man whose contributions to this country cannot be denied, but he was also a man who adhered to the racist views of the period. This is an undeniable truth.

Thankfully, the folks at Monticello are not shying away from this aspect of Jefferson's life and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has made great strides to include an African-American presence in its presentation. This effort not only fills the void of a far-too-neglected history, but it also makes Thomas Jefferson human. Visitors today will more likely leave Thomas Jefferson's Monticello with a broader understanding of this remarkable, yet flawed Founding Father.

- Michael Aubrecht