BLOG, or DIE. Author Bio

Friday, 1 April 2011

That's not what I heard...

Have you ever wondered how the Revolutionary War is taught in England? Last night I did a little research on the Internet and came upon several message boards where Americans and Brits were discussing this topic. The general consensus that I gathered is that they do not discuss the Revolution in the UK. At first glance this sounds preposterous, but we have to remember that England’s history goes back centuries before ours even started. As a result, what was THE seminal event in our nation’s history is just another footnote in theirs. A student from Oxford University posted that on the rare occasion it is discussed, they refer to it as “The War of Independence.” He added that his history classes dealt with British social-history (how the Elizabethans, Romans, Victorians lived) in Primary school (11-) and 20th-Century political history (Nazi Germany, Cold War) between ages 11 -18. The only “American history” he remembered learning about was the Civil Rights Movement.

One graduate student from London posted that the American Revolution was briefly discussed during his education, but in an impartial manner which differed greatly from our romanticized version. He added that many of the “myths” surrounding the event were more readily dispelled in his classrooms. The example offered up was the Boston Tea Party. According to his teachers the protest took place because taxes were too low, not too high (some readers may be surprised to know that taxes were far higher in England than they were in the colonies). In addition he was told that King George III had little power over the colonists meaning the rebellion was actually against the policies of the British Parliament and Prime Minister, not the King.

Another disparity between the US and UK versions was how the war was lost. As British forces were the best equipped and trained army on the planet, it seems impossible that a band of citizen soldiers could defeat them. One UK student said he was taught that the war had ended because British troops were needed elsewhere, not that they were defeated by the Continental Army. Another confessed he was told that the army had simply quit when it became too difficult for them to maintain a supply line across the ocean. I found it very interesting that none of the Brits taking part in this conversation countered either of these claims. (It reminded me very much of the debates I’ve witnessed over the Civil War when folks argue whether the Confederate Army was defeated by the Federals or simply collapsed due to logistics.)

The biggest difference when comparing the US and UK versions appears to be whether the colonists were better off as a result of gaining their independence. According to the UK posts, life without England was dramatically worse for many, especially African-Americans as the British Empire abolished slavery in 1805, 60 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. Their theory being that the slave trade would have been eradicated much sooner if the colonies had remained under British rule. Additionally they believe that if America had waited a few more years, the British North America Acts would have likely permitted them to have their own elected Parliament, just like Canada.

In the end most of the UK students participating in the discussion agreed that they had been taught very little or nothing at all about the Revolution. Fewer cared until they got older and began to take an interest in world history. So what have we learned? Obviously there are two sides to every war, each with a different perspective and recollection. The Revolutionary War (or War for Independence depending on which side of the ocean you’re on), is of particular significance as it resulted in the birth of a new country. It is the quintessential example of “David slaying Goliath.” We Americans celebrate the event, while Englishmen tend to ignore it.

I wonder if the Israelites and Philistines did the same?

Thursday, 31 March 2011

An Ugly Truth

Of all the topics that I have written about as a historian none is more complex than the institution of slavery. You may recall the feature that I penned for Patriots of the American Revolution titled: “Race and Remembrance at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello,” or the three-part series presenting a multi-racial view for The Jefferson Project titled “Jefferson and Slavery: Thoughts in Black and White.” I also blogged about: George Washington the emancipating slaveholder, racism and recruiting in the Continental Army, the realities of the 3/5’s Compromise and recollections of Christmas and slavery at Monticello. I am hoping to write an essay that further explores the story of Issac Jefferson as I feel like I am only beginning to scratch the surface of this topic.

You don’t have to be a historian to struggle with this subject. Even those with only a passing interest in our past can find racism difficult to discuss. Oftentimes we take the easy way out by telling ourselves to simply “keep things in context” and “not judge the past by comparing it to the present.” We remind ourselves that what was once commonplace then - isn’t commonplace now. This affirmation helps to dull the sting of racism. The most difficult part (in my opinion) of examining race and our country’s origin is admitting that our Founding Fathers were racist. In order to do that, we must reveal the faults in our heroes. After all these were some of the most brilliant men who ever lived, men who we owe the greatest debt of gratitude to, men who literally did the impossible by establishing a new nation dedicated to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If we were in ancient Greece these men would be our gods.

But…these titans of patriotism were also men who fought for freedom, while simultaneously depriving it to an entire race of people. We know that for certain. Yet in spite of this hypocrisy we are able to reconcile the faults of our Founders when celebrating their life. Who hasn’t admired George Washington’s courage or Thomas Jefferson’s brilliance when visiting Mount Vernon or Monticello? I certainly have. How many of us forget that they were also slaveholders? In recent years Mount Vernon and Monticello have both taken great steps to include the story of African-Americans in their exhibits. This effort has brought about a deeper understanding of slavery in relation to these men, but it still hasn’t enabled us to truly relate to them. To some people, the Founding Fathers are beyond reproach, while others vehemently condemn them. I believe that these extreme-attitudes do a great disservice to their memory. We must remember that they were human, capable of greatness and shamefulness.

My theory is that it is impossible for us to properly judge the Founders because we simply cannot relate to their time and place. We can’t relate because these men were never presented to us in any other capacity. Their likenesses grace our monuments and money. Our forefathers put them up on a pedestal where we continue to herald their achievements today. At the same time we forget that they once viewed African-Americans as property. This is where their racism is most evident. We react to this disturbing fact by subconsciously quantifying the issue to make it more acceptable. We remind ourselves that Washington freed his slaves upon his and his wife’s death and that Jefferson is believed to have fathered children with one of his. This rationalization dulls the sting of their prejudice.

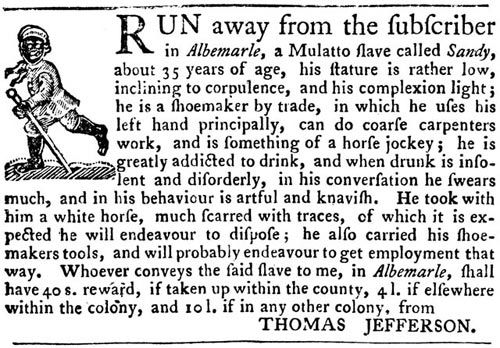

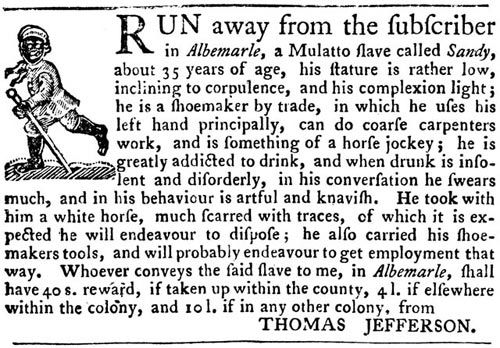

The harsh reality is that no matter how 'well' a slaveholder treated their slaves, at the end of the day they were still slaveholders. A brutal example of this can be found in the inventory records of slaves that were kept by the overseers, as well as the advertisements that they placed in papers. These artifacts prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that these men viewed African-Americans as inferior.

The example above was placed in the September 14, 1769 issue of the Virginia Gazette by Thomas Jefferson who was offering a reward for the return of a runaway slave named Sandy. We know much about the life of the slaves on Mulberry Row and of Jefferson’s affection for many of them. At the same time we see here that he considered them personal property. Therein lays the conflict between admiring our Founders contributions while acknowledging their imperfections. It is a challenge that I still wrestle with no matter how much I read or write about the subject.

Tuesday, 29 March 2011

Franklin on Farting

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Among his many contributions to society, Ben Franklin was also a scientist. While living as an ambassador in France Franklin grew disgusted with what he considered to be an elitist’s-approach to science. He believed that too many academic societies were growing increasingly pretentious and far too concerned with the impractical. The Royal Academy of Brussels was an exceptionally arrogant institution in Franklin’s opinion and became the brunt of one of his most notorious essays.

In 1781 Franklin penned “A Letter To A Royal Academy,” which was later more appropriately titled “To the Royal Academy of Farting.” This brilliantly sarcastic letter was in direct response to a call for scientific-papers from the academy. Franklin’s essay called for research into the far-too neglected subject of improving the odor of human flatulence. The original letter was sent to a Welsh philosopher named Richard Price who had an ongoing correspondence with the good doctor. The introduction stated:

I have perused your late mathematical Prize Question, proposed in lieu of one in Natural Philosophy, for the ensuing year...Permit me then humbly to propose one of that sort for your consideration, and through you, if you approve it, for the serious Enquiry of learned Physicians, Chemists, &c. of this enlightened Age. It is universally well known, That in digesting our common Food, there is created or produced in the Bowels of human Creatures, a great Quantity of Wind. That the permitting this Air to escape and mix with the Atmosphere, is usually offensive to the Company, from the fetid Smell that accompanies it. That all well-bred People therefore, to avoid giving such Offence, forcibly restrain the Efforts of Nature to discharge that Wind.

Read the entire letter here.

Franklin’s theory followed in which he discussed how certain foods could affect the severity of flatulence odor. He then called for sanctioned scientific testing to take place while challenging scientists to work toward creating a drug, “[w]holesome and not disagreeable,” which can be mixed with what he called “common Food or Sauces” to render flatulence as agreeable as perfume. He closed the piece by saying that compared to the practical applications of his proposal, all other sciences were “scarcely worth a FART-HING.”

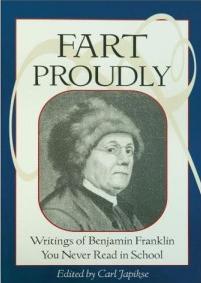

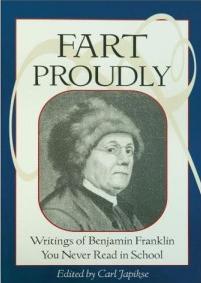

A reprint of this letter was privately published by Franklin and distributed exclusively among his friends. After his death the letter was excluded from any future publishing until Fart Proudly: Writings of Benjamin Franklin You Never Read in School, a collection of Franklin's humorous and satirical writings was published in 1990.

Sunday, 27 March 2011

Two wars with the S.C. Dragoons

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment.

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment.

The Charleston Light Dragoons boast a storied history that stretches from America’s fight for independence to the War Between the States. Founded around 1773, this group of South Carolina mounted infantrymen was originally formed as the Charleston Horse-Guards. During the Revolutionary War, they were known as the Charleston Light Dragoons. The first captain of this unit was a man named Samuel Prioleau whose descendents would ride together as members of Company K, in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry (one being wounded at Pocotaligo and the other falling at Cold Harbor). Their sacrifice followed a long lineage of service by their forefathers. In order to fully appreciate the legacy of this elite unit, one must begin at their beginning.

The original Charleston Horse-Guards were established to perform the duties of reconnaissance and patrolling. Acting in the capacity of mounted militia, these dragoons were among South Carolina’s first cavalrymen or scouts. Eventually the bravado of these units led to an expansion of roles to include combat. Unfortunately, it would be friendly fire that would deal one of the most costly blows to the regiment. According to A Sketch of the Charleston Light Dragoons From the Earliest Formation of the Corps by Edward Wells:

In the stormy times of the Revolution the command is believed to have consisted as several companies. This was the case in 1777 when Major Benjamin Huger, with a detachment from the corps, rode out of the lines in Charleston to reconnoiter for the expected approach of British forces. Not having discovered the enemy in the vicinity, he was bringing his men back, and had reached a point in what is now Meeting street near the Citadel, when they were fired upon with grape from a field piece, in command presumably of some militiamen, who mistook them for the King’s troops. Huger was killed. General Hampton, grandfather of the present general, at that time with the detachment, was riding “boot-leg and boot-leg,” as he expressed it, with Major Huger. The relative of this latter gallant gentleman, the inheritor of his name, and the strong characteristics of the blood, fought under the flag of the Dragoons at Pocotaligo, Hawes-shop, and other hotly contested fields.

In the months leading up to the Civil War the Charleston Light Dragoons were mentioned among the troops guarding Fort Sumter in 1860. They would later join a number of South Carolina militia companies who were consolidated into the 4th South Carolina Cavalry. The 4th S.C. regiment was organized in 1862, by consolidating the 10th and 12th Battalion South Carolina Cavalries into 10 companies including Company K, the former Light Dragoons out of Charleston.

Referred to as an “anomalous unit,” the ranks of the Co. K were reputed to be so exclusive that officer’s resigned their own commissions to serve with ordinary enlisted troops. It is said that the unit carried themselves with a unique flair and a natural assumption of social superiority even over fellow Confederate cavalry. W. Eric Emerson outlined the aristocratic attitudes of the Charleston Light Dragoons, as part of the 4th South Carolina Cavalry in his book Sons of Privilege: The Charleston Light Dragoons in the Civil War. According to the book’s teaser:

Organized much like a gentleman’s social club, the dragoons differed markedly from most units in the Confederate and Union armies, which brought together men of varying social and economic backgrounds. Emerson vividly depicts the dragoons’ two assignments—a relatively undemanding stint along the South Carolina coast and a subsequent few weeks of intense combat in Virginia. Recounting the unit’s 1864 baptism by fire at the Battle of Haw’s Shop, he suggests that the dragoons’ unrealistic expectations about their military prowess led the men to fight with more bravery than discretion. Thus the unit suffered heavy losses, and by 1865 only a handful survived.

Upon its reformation, the 4th S.C. was commanded by Colonel B. Huger Rutledge and served in the 1st Military District of South Carolina from December 1862 until it was transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia in March 1864. Serving under Major General Hampton's Division of cavalry, in the Cavalry Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, they would eventually be transferred to the Army of Tennessee under General Joseph E. Johnston. While under Johnston’s command they saw continuous action in the Campaign of the Carolinas through the spring of 1865, completing their wartime service with less than 200 men.

Sources:

A Guide to South Carolina Civil War Research (The Charleston Light Dragoons)

Historical Sketch and Roster of the SC 4th Cavalry Regiment by John C. Rigdon

A Sketch of the Charleston Light Dragoons From the Earliest Formation of the Corps by Edward Wells

Sons of Privilege: The Charleston Light Dragoons in the Civil War by W. Eric Emerson

Thursday, 24 March 2011

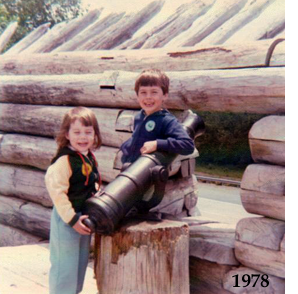

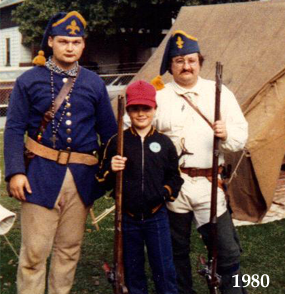

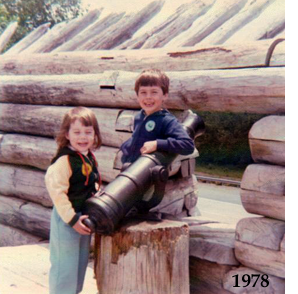

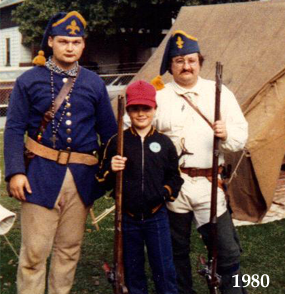

Ligonier Days

Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places, Fort Ligonier, wasn’t too far from our home in Pittsburgh. I remember traveling there on a number of occasions and credit that site in particular for my interest in 18th-century history.

Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places, Fort Ligonier, wasn’t too far from our home in Pittsburgh. I remember traveling there on a number of occasions and credit that site in particular for my interest in 18th-century history.

Unlike Fort Pitt, Fort Ligonier was completely reconstructed and therefore able to hold the attention of a hyper-active child like myself. I believe that my first exposure to re-enactors took place during “Ligonier Days” a three-day festival when living historians, dressed-up as British soldiers and Indians, demonstrated their weapons and tactics. The memory of that event is still very vivid as I was captivated by the experience.

Located in southwestern Pennsylvania, Fort Ligonier was constructed in 1758 for use as a British garrison. During its lifetime, the stronghold served multiple purposes including time as a port of passage for troops en route to Fort Pitt, and as a vital link for the British Army’s supply lines. A number of regulars were stationed there including the 60th Regiment of Foot (Royal Americans), the First Highland Battalion (Montgomery’s Highlanders), the 77th Regiment of Foot, a Royal Artillery detachment, the 94th Regiment of Foot (Royal Welsh Volunteers) and the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment of Foot (Black Watch). Fort Ligonier’s proximity to the French garrison at Fort Duquesne also made it a target.

Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians were driven back by artillery. As darkness fell the remaining forces renewed their attack before retreating back into the woods. The casualty reports following the four-hour assault differed greatly as the French reported taking 100 scalps and seven prisoners, while the British only reported 12 killed, 18 wounded, and 31 missing.

Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians were driven back by artillery. As darkness fell the remaining forces renewed their attack before retreating back into the woods. The casualty reports following the four-hour assault differed greatly as the French reported taking 100 scalps and seven prisoners, while the British only reported 12 killed, 18 wounded, and 31 missing.

In November of that year General John Forbes assumed custody of the newly abandoned Fort Duquesne. He designated the site “Pittsburgh” to honor William Pitt, the acting Secretary of State. He then christened the fort known as Loyalhanna "Fort Ligonier," after his superior Sir John Ligonier, commander in chief in Great Britain.

During the Pontiac’s War of 1763, a coalition of Native American tribes attacked a number of forts in protest of British policies following the French and Indian War. Fort Ligonier was attacked twice and besieged by Indians who were eventually defeated at the Battle of Bushy Run. Three years later the fort, was decommissioned and handed over to a caretaker named Arthur St. Clair. In 1765, the Provost William Smith from the College of Philadelphia declared the importance of the site stating, “The preservation of Fort Ligonier was of the utmost consequence.”

Despite the absence of war the region around Fort Ligonier remained a dangerous one deep into the next decade. In November of 1777 a commissary named Samuel Craig Sr. was summoned to the garrison. While en route he was captured by Indians near an area called Chestnut Ridge. All efforts to locate the man failed, although his horse was found shot dead, surrounded by fragments of torn paper. Craig and his three eldest sons, John, Alexander and Samuel Jr., had served in the Revolutionary War prompting the belief that he had attempted to defend himself against hostiles.

Several acres of the garrison’s property were preserved and the above-ground elements were rebuilt. The inner-fort is 200 square-feet with four bastions, one on each corner. According to the site’s website the fort can be accessed by three gates where “…inside is the officers’ mess, barracks, quartermaster, guardroom, underground magazine, commissary, and officers’ quarters. Immediately outside the fort is General Forbes’s hut. An outer retrenchment, 1,600 feet long, surrounds the fort. Other external buildings include the Pennsylvania hospital (two wards and a surgeon’s hut), a smokehouse, a saw mill, bake ovens, a log dwelling and a forge.”

The transcripts of a journal detailing the fort's construction are available in the Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania. Volume Two, The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania, Fort Ligonier by Clarence M. Busch, State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1896.

Today a museum compliments the fully-restored Fort Ligonier and features a collection of George Washington relics including his saddle pistols, an 11-page memoir on the French and Indian War and a Rembrandt Peale portrait. Washington had served there as a young colonel of the Virginia Regiment in service to the British Crown. A long-term installation titled “The World Ablaze: An Introduction to the Seven Years’ War” is on exhibit there. This unique collection features over 200 British, French and Native American items.

Not much has changed since I first visited Fort Ligonier as a kid. Each year thousands of tourists from all over the world travel to southwestern PA to experience life in the 1700’s. This includes busloads of children who flock to “Ligonier Days” just like I did. I have no doubt that there are plenty of future historians among them guaranteeing that the legacy of this historical gem will be preserved for generations to come. For more information or to plan your trip, visit the Fort Ligonier website.

Newer | Latest | Older

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.

Let me begin by saying that this post is absolutely 100% true. I read about it last year while studying a biography of Benjamin Franklin and I have wanted to write about it for quite some time. At first glance this story may sound like the lead-in to a punch line, but I can assure you that there is no joke. Those of you that are familiar with the REAL Ben Franklin will no doubt agree that he was quite capable of doing this.  Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment.

Today I spent the afternoon touring the Museum of the Confederacy with my son who is home from college. On this visit I looked for something that would tie in with my new focus on the Revolution. I’ve wanted to write something that combines my interest in both Civil War and Colonial history for quite some time. One of the MOC's display cases featured this Roman-Greco style helmet that belonged to a cavalryman in the 4th South Carolina Cavalry, originally dubbed the Charleston Light Dragoons. Members wore this unique style of helmet that recalled the days of their forefather's regiment. Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places,

Whenever someone asks what sparked my interest in American history, I always give the same answer, my parents. Over the years I had some excellent teachers who cultivated my interest, but no one else promoted the subject more than my mom and dad. Looking back I fondly recall dozens of family trips to historical sites like Monticello, Gettysburg, Williamsburg and the Drake Oil Well. One of our favorite places,  Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians

Originally referred to as “The Post at Loyalhanna,” Ligonier came under fire on October 12, 1758 during the French and Indian War. Still under construction, the garrison was barely able to repel its attackers who boasted much higher numbers. After decimating British troops who were stationed outside the walls, the French and Indians